↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Semi-implicit variational inference (SIVI) enhances the flexibility of variational distributions, but existing methods face challenges like intractable densities and reliance on approximations. These limitations hinder direct ELBO optimization, often necessitating costly inner-loop MCMC or minimax solutions. This is problematic as it introduces computational inefficiency and limits the method’s expressiveness.

The proposed Particle Variational Inference (PVI) tackles these issues head-on. PVI utilizes empirical measures to approximate optimal mixing distributions, directly optimizing the ELBO without parametric assumptions. This novel approach, grounded in the Euclidean-Wasserstein gradient flow, offers a computationally efficient and flexible alternative. Empirical results showcase PVI’s favorable performance compared to existing SIVI methods across diverse tasks, demonstrating its potential as a superior approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it proposes Particle Variational Inference (PVI), a novel method for semi-implicit variational inference (SIVI) that directly optimizes the evidence lower bound (ELBO) without resorting to approximations or costly computations. This offers a more efficient and expressive approach to variational inference, addressing limitations of existing SIVI methods. The theoretical analysis of the gradient flow provides a solid foundation for understanding the algorithm’s behavior and convergence properties, making it a significant contribution to the field. PVI’s improved efficiency and expressiveness open up new avenues for applying variational inference to complex problems, particularly in Bayesian deep learning.

Visual Insights#

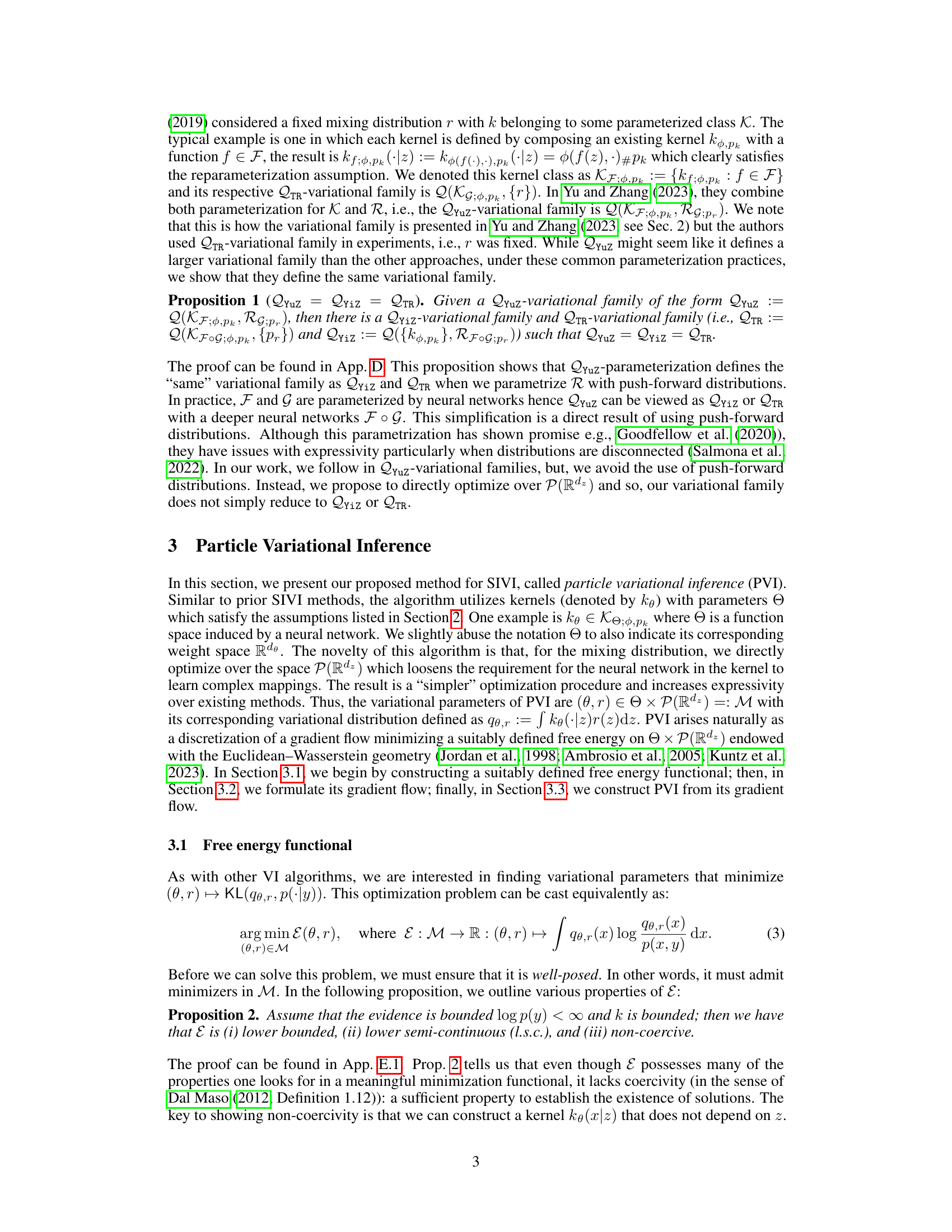

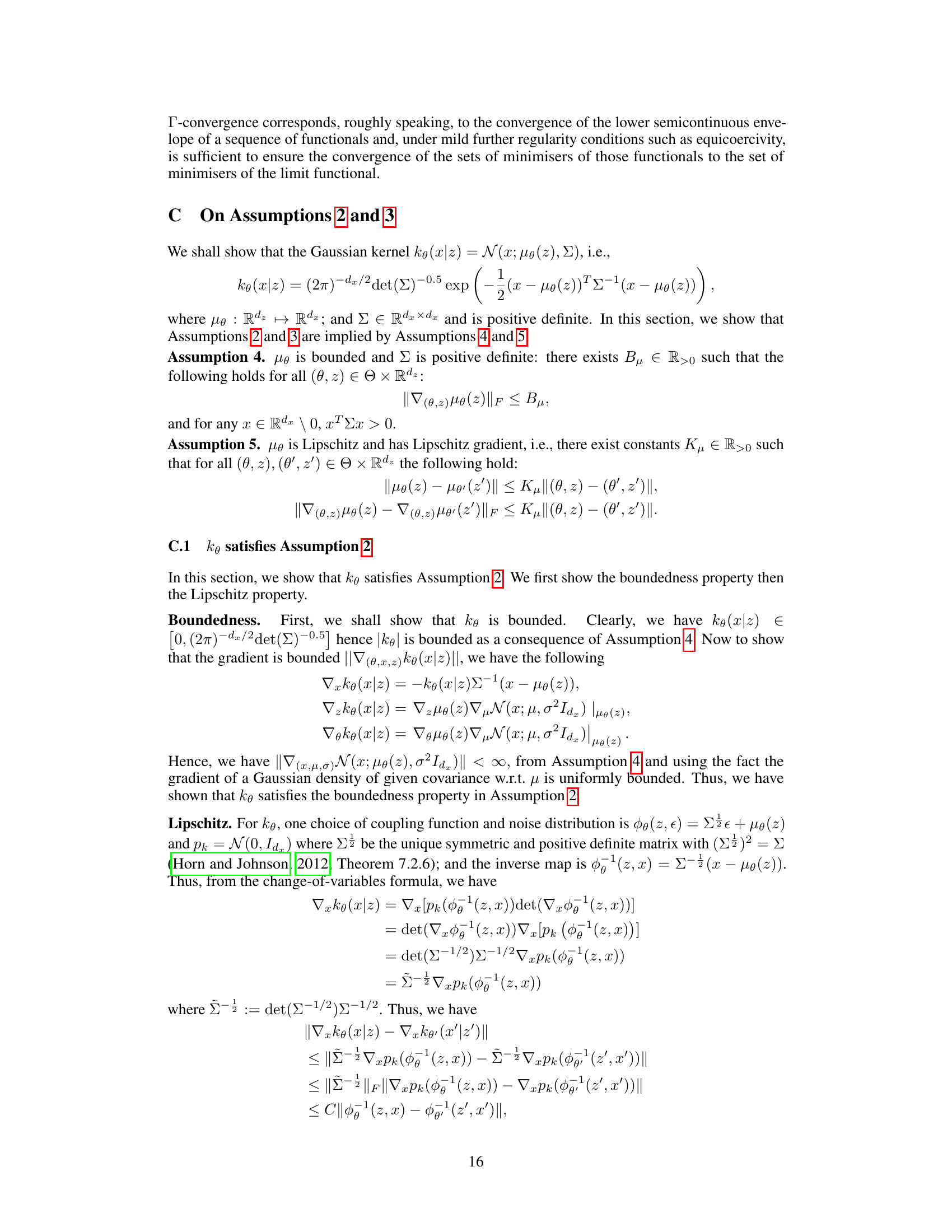

This figure compares the performance of Particle Variational Inference (PVI) and its variant with a fixed mixing distribution (PVIZero) on a bimodal Gaussian mixture dataset. It shows the learned density (qθ,r) produced by each method and the kernel density estimate (KDE) of the mixing distribution (r) learned by PVI using 100 particles. The comparison is performed across different kernel choices (Constant, Push, Skip, LSkip), demonstrating how the expressiveness of the mixing distribution affects the final density estimation under different kernel types.

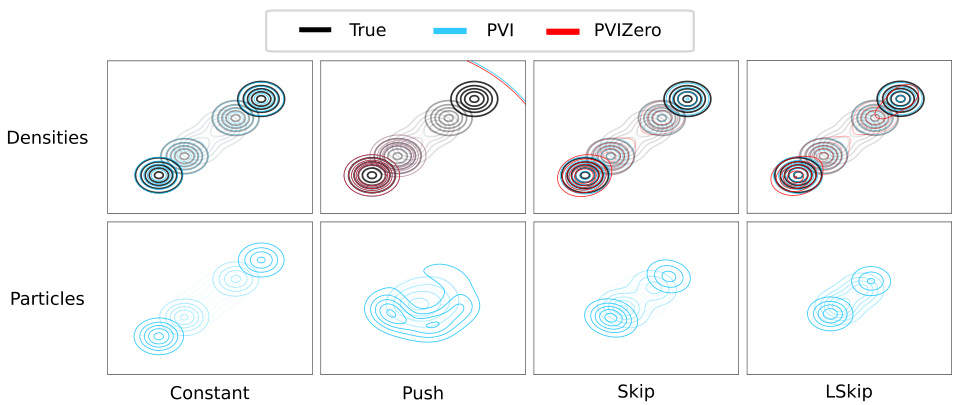

This table presents the results of a comparison of four different semi-implicit variational inference algorithms on three toy density estimation problems. The performance of each algorithm is evaluated using two metrics: the rejection rate (p) from a two-sample kernel test, and the sliced Wasserstein distance (w) between the estimated density and the true density. Lower values for both metrics indicate better performance. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of these metrics across 10 independent trials for each algorithm and problem.

In-depth insights#

SIVI’s limitations#

Semi-implicit variational inference (SIVI) methods, while offering increased expressiveness in variational inference, suffer from several limitations. Existing SIVI approaches often rely on intractable variational densities, necessitating the use of surrogate objectives like optimizing bounds on the ELBO or employing computationally expensive MCMC methods. The parameterization of the mixing distribution in SIVI is often complex, making it difficult to learn effectively and leading to issues such as mode collapse in multimodal posteriors. The optimization landscapes of SIVI methods can be challenging, leading to instability and difficulties in achieving convergence. Prior methods often make strong assumptions about the mixing distributions, limiting the flexibility and applicability of the approach. Furthermore, the theoretical analysis of SIVI often lags behind empirical results, hindering a deeper understanding of its behavior and potential pitfalls. Addressing these limitations is crucial for fully realizing the potential of SIVI as a powerful tool for Bayesian inference.

PVI algorithm#

The Particle Variational Inference (PVI) algorithm offers a novel approach to Semi-implicit Variational Inference (SIVI) by directly optimizing the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO) using a Euclidean-Wasserstein gradient flow. Unlike previous SIVI methods that rely on approximating the ELBO or employing computationally expensive MCMC methods, PVI uses empirical measures to approximate the optimal mixing distribution, thus avoiding intractable variational densities. This is achieved by discretizing the gradient flow, resulting in a practical algorithm that directly optimizes the ELBO without making parametric assumptions about the mixing distribution. A key advantage of PVI is its enhanced expressiveness, allowing it to capture complex properties of the posterior distribution that traditional variational families may fail to capture. The theoretical analysis of PVI demonstrates the existence and uniqueness of solutions for the gradient flow, as well as the propagation of chaos results, providing strong theoretical support for the algorithm’s effectiveness. The algorithm’s simplicity and direct optimization of the ELBO, combined with its strong theoretical foundation, makes PVI a significant advancement in SIVI, offering a promising alternative to existing methods that suffer from computational constraints or suboptimal approximations.

Gradient flow#

The concept of a gradient flow is central to the proposed Particle Variational Inference (PVI) method. It frames the optimization problem as a continuous-time dynamical system, moving through the space of variational parameters. This approach elegantly handles the complexity of optimizing over a high-dimensional space of probability distributions. The gradient flow, in this context, directly targets the minimization of the free energy functional, providing a principled and potentially efficient method for semi-implicit variational inference. The free energy functional is a regularized version that ensures the well-posedness of the minimization problem. By discretizing the gradient flow, PVI provides a practical algorithm that avoids reliance on computationally expensive upper bounds or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, while offering theoretical guarantees on convergence. The theoretical analysis of the gradient flow establishes the existence and uniqueness of solutions, further solidifying the foundation of the PVI methodology. The choice of using a Euclidean-Wasserstein geometry in the gradient flow framework is particularly noteworthy, as it addresses the challenges of optimizing over the space of probability measures in a principled manner.

Mixing dist impact#

The section ‘Mixing dist impact’ investigates the significance of the mixing distribution in semi-implicit variational inference (SIVI). The authors posit that optimizing the mixing distribution, rather than fixing it, allows the model to capture complex properties like multimodality, which the kernel alone may struggle with. Experiments using various kernels (constant, push, skip, LSkip) demonstrate that PVI, which directly optimizes this distribution, outperforms methods using fixed distributions, especially as the complexity of the true posterior increases. This highlights that a flexible mixing distribution is vital for learning complex, multimodal posteriors, demonstrating the expressiveness gained by the PVI approach. The results emphasize a key advantage of PVI—its ability to represent expressive and complex posterior distributions without relying on complex kernel design. This contrasts sharply with earlier SIVI methods, which primarily focused on complex kernel parametrization. Therefore, the mixing distribution, freely optimized in PVI, emerges as a crucial component for enhanced model performance and flexibility in SIVI.

Future work#

The authors suggest several promising avenues for future research. Addressing the non-coercivity of the free energy functional is a crucial theoretical challenge, impacting the algorithm’s convergence guarantees. Investigating alternative regularizers or modifying the functional itself could lead to stronger theoretical foundations. Extending the theoretical analysis to the y=0 case is also vital, as this setting directly corresponds to the practical application. The current theoretical analysis relies on a regularized version. Exploring the impact of different kernel choices on PVI performance is another area of interest, especially focusing on developing kernels specifically designed to improve the algorithm’s efficacy with complex multimodal data. Finally, empirical evaluation on a wider range of datasets and tasks is essential to further validate the generality and scalability of the proposed method. In particular, more robust and controlled experiments would help confirm the practical efficiency and advantages of optimizing the mixing distribution in SIVI methods.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares the performance of Particle Variational Inference (PVI) and its variant with a fixed mixing distribution (PVIZero) on a bimodal Gaussian mixture. It visualizes the estimated probability density functions (PDFs) produced by both methods, using different kernel choices. The KDE plot shows the learned mixing distribution (r) approximated by 100 particles in PVI, demonstrating the model’s ability to learn a complex mixing distribution.

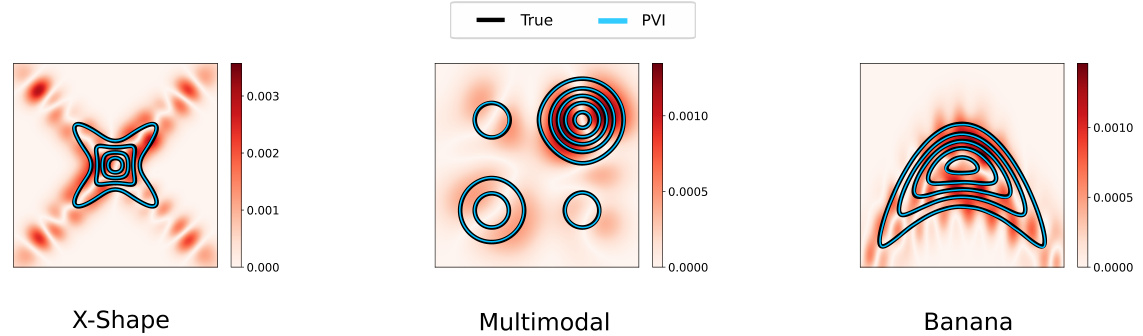

This figure compares the performance of different semi-implicit variational inference methods (PVI, UVI, SVI, SM) against Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for Bayesian logistic regression. Panel (a) displays pairwise and marginal posterior distributions for three randomly selected weights (x1, x2, x3) to visually assess the accuracy of each method in approximating the true posterior. Panel (b) provides a scatter plot comparing the correlation coefficients calculated from the MCMC samples against those obtained from each SIVI method for a more quantitative evaluation of their performance. The diagonal line in panel (b) represents perfect correlation.

More on tables

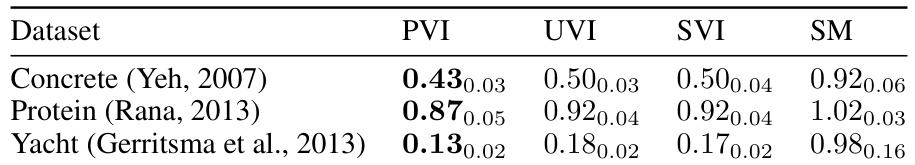

This table shows the root mean squared error for Bayesian neural networks on three different datasets: Concrete, Protein, and Yacht. The results are averages over 10 independent trials, with standard errors also reported. The lowest error for each dataset is highlighted in bold, allowing for comparison of the performance of different methods (PVI, UVI, SVI, SM).

This table presents the results of toy density estimation experiments using four different methods: PVI, UVI, SVI, and SM. The table shows two key metrics for each method: the rejection rate (p) from a two-sample kernel test and the sliced Wasserstein distance (w) which quantifies the distance between the estimated and true distributions. Lower values for both metrics indicate better performance. The table also highlights statistically significant results and best performing methods.

This table presents the results of toy density estimation experiments comparing several semi-implicit variational inference methods. It shows the rejection rate (p-value from a two-sample test) and the average Wasserstein distance (w) for each method. Lower values are better, indicating a more accurate approximation of the target density. Standard deviations are included to show the variability of the results. Bold values highlight cases where the p-value is below the 0.05 significance level, showing significant agreement with the target density, and also identifies the method with the lowest Wasserstein distance.

Full paper#