↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current vision models heavily rely on “on-the-grid” representations, where each layer’s tokens correspond to specific image locations. This limits their ability to track scene elements consistently across time, especially in videos with motion. This is a major limitation when it comes to many downstream tasks, such as object tracking and action recognition, which require observing how objects change their configuration over time regardless of their location in the image.

To address these limitations, the paper introduces Moving Off-the-Grid (MooG), a self-supervised video representation model. MooG uses a combination of cross-attention and positional embeddings to allow tokens to move freely and track scene elements consistently over time. This approach outperforms “on-the-grid” baselines and achieves competitive results with domain-specific methods on tasks such as point tracking, depth estimation, and object tracking. MooG provides a strong foundation for various vision tasks by decoupling the representation structure from the image structure and enabling consistent tracking of scene elements.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to video representation learning that significantly improves performance on various downstream tasks. It challenges the prevailing “on-the-grid” paradigm, offering a new foundation for future research in video understanding. The proposed method’s strong performance and adaptability open up new avenues for self-supervised learning and the development of more robust and generalizable video representations.

Visual Insights#

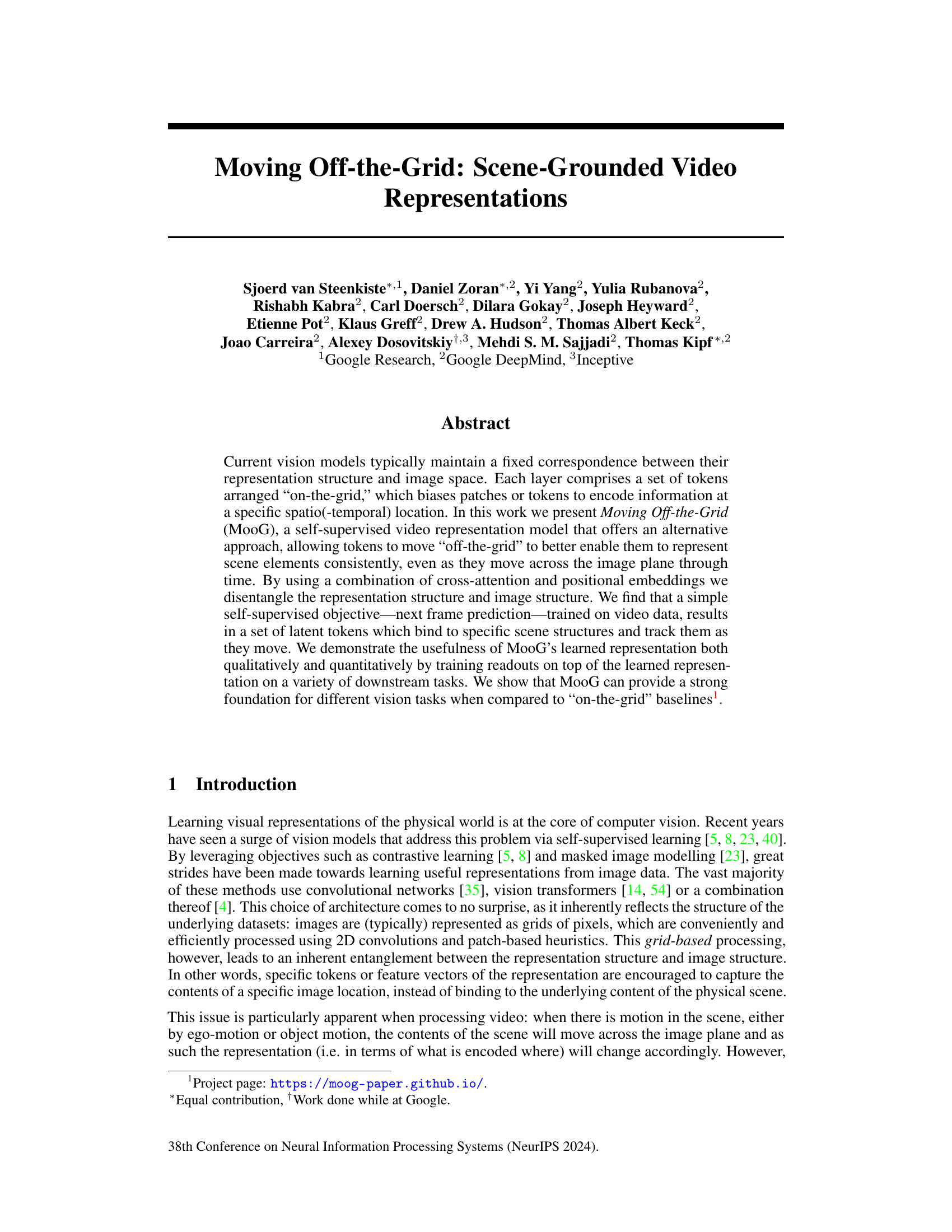

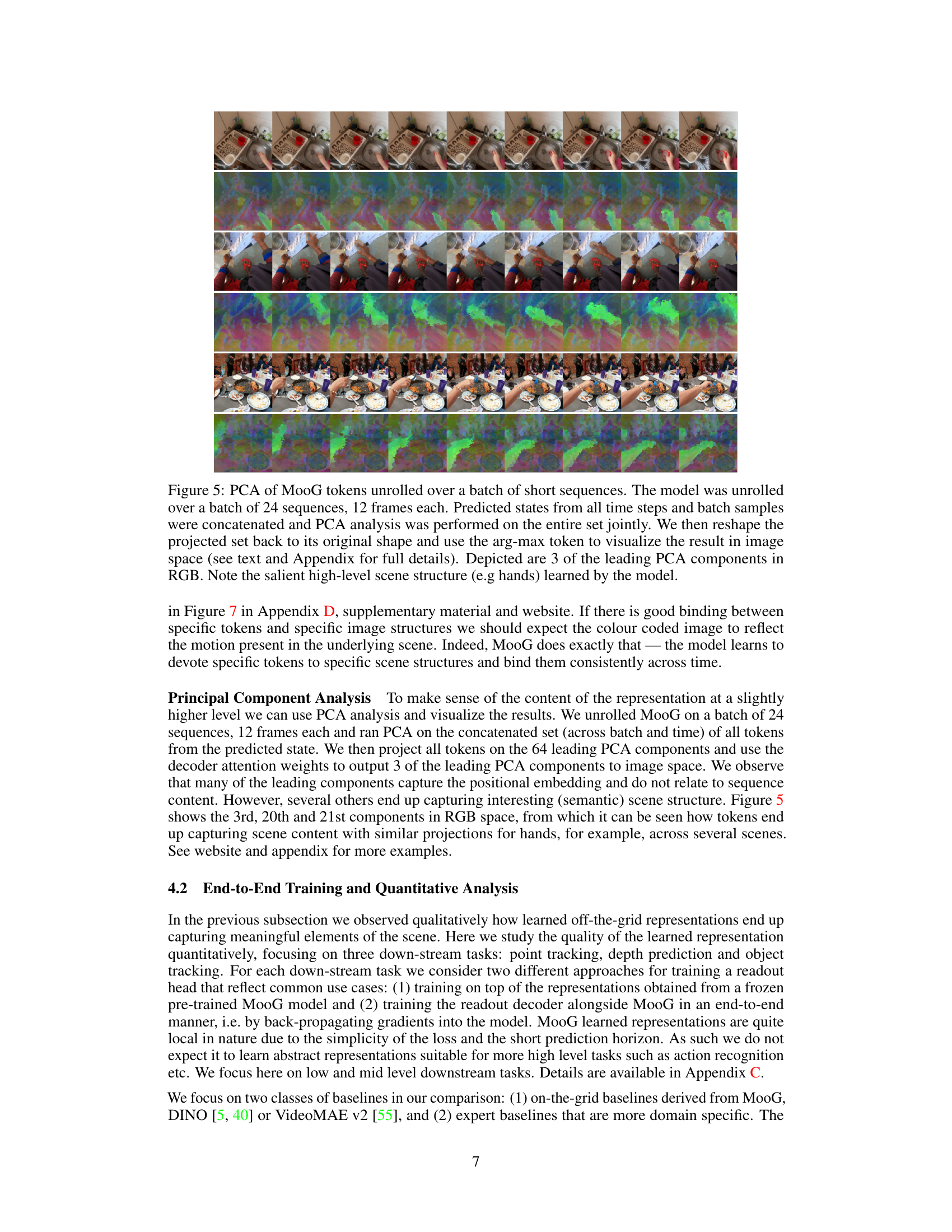

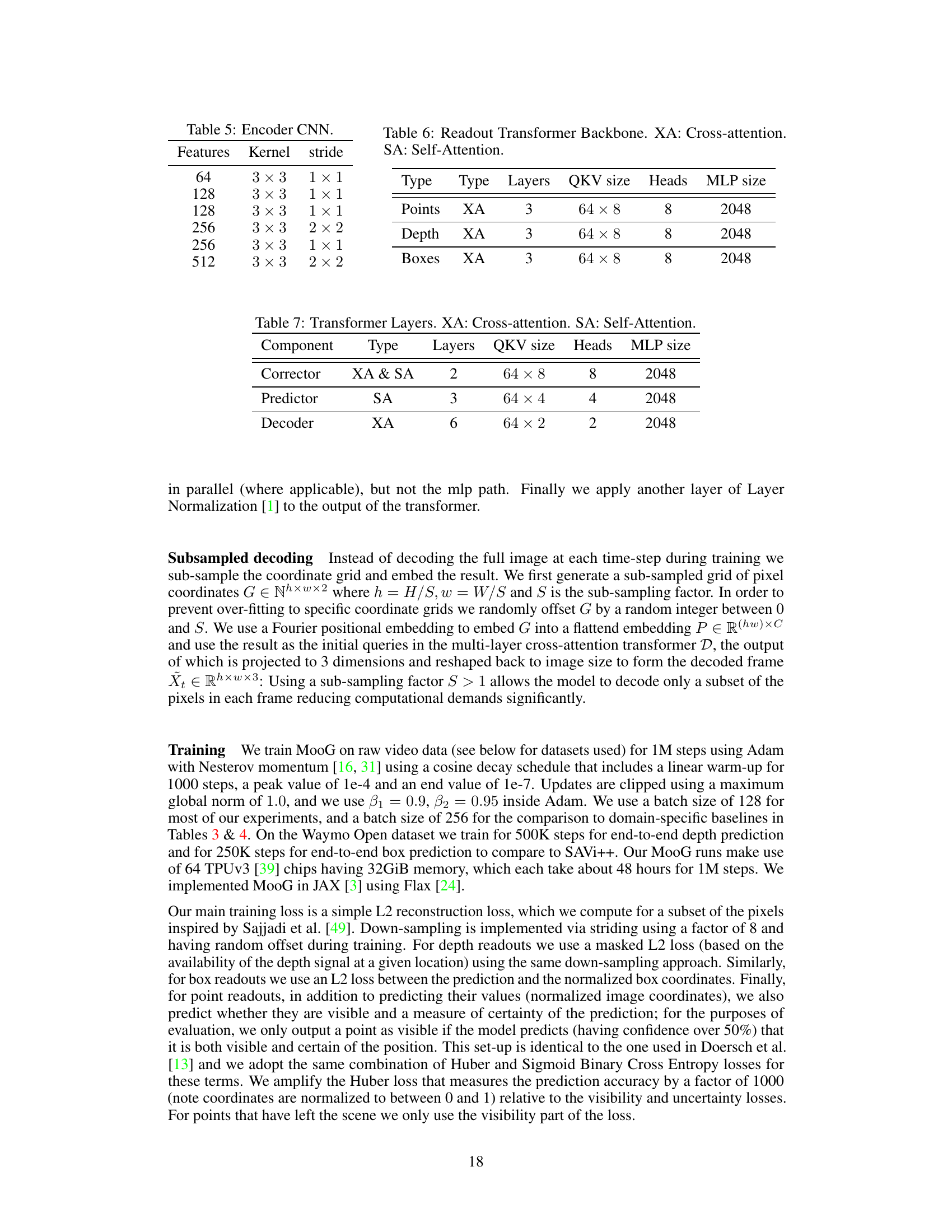

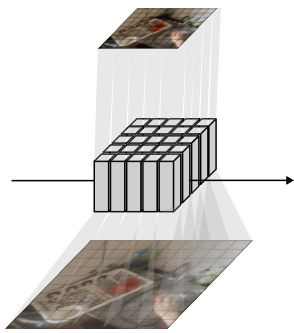

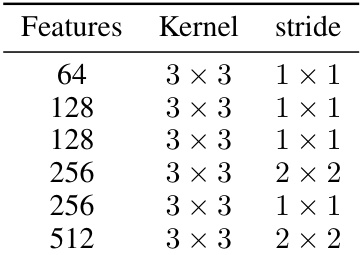

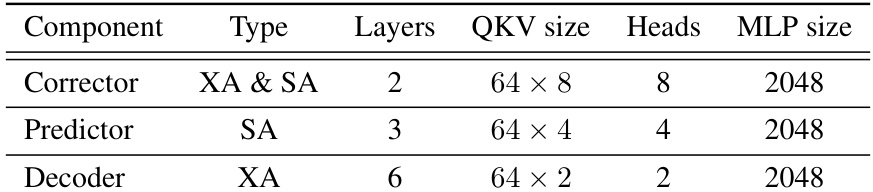

This figure illustrates the MooG model architecture. MooG is a recurrent model that processes video frames sequentially, learning a set of ‘off-the-grid’ latent representations. The process involves three main networks: a predictor, which forecasts the next predicted state; a corrector, which encodes the current frame and refines the prediction; and a decoder, which reconstructs the current frame from the predicted state. The model iteratively updates its representation as new frames are observed. This ‘off-the-grid’ approach allows the model to track scene elements consistently even when they move across the image plane.

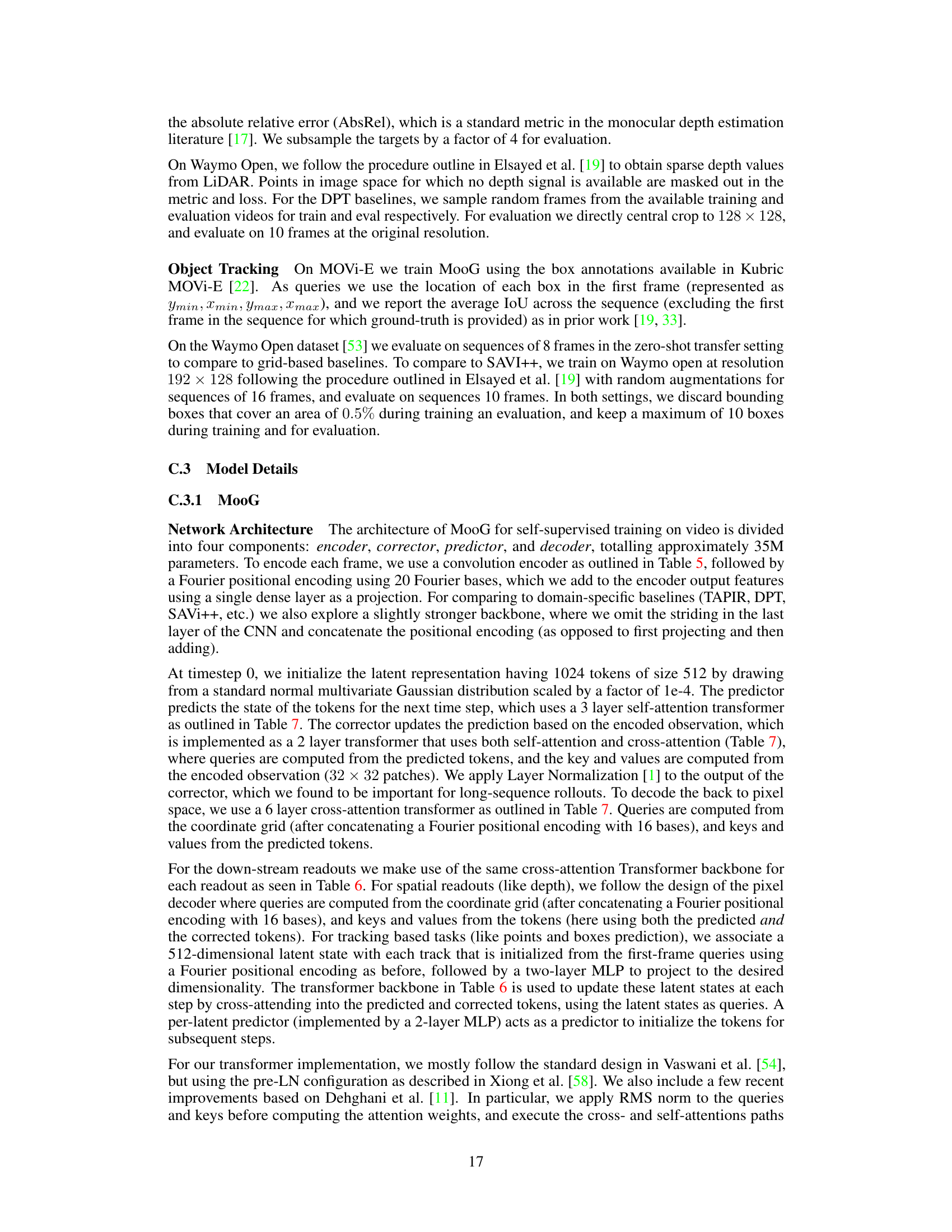

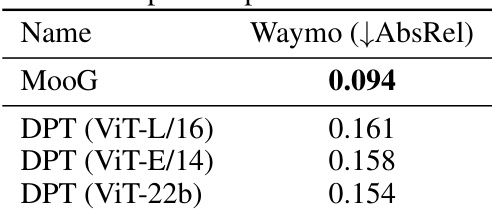

This table presents the performance of different models on three downstream tasks (point tracking, depth estimation, and bounding box detection) using frozen representations. It compares MooG against several baselines including DINO and VideoMAE v2 with different ViT encoder sizes (small, base, giant), and grid-based versions of MooG. The table highlights the number of parameters for each model, showing that MooG uses considerably fewer parameters than the larger baselines.

In-depth insights#

Off-Grid Video#

The concept of “Off-Grid Video” in the context of computer vision represents a paradigm shift from traditional grid-based approaches. Instead of relying on fixed spatial locations (like pixels or image patches) to represent information, off-grid methods focus on dynamic, scene-centric representations. This means that tokens or features in the model are free to move and associate with scene elements as they change position over time, regardless of camera motion or object movement. This approach offers significant advantages in handling motion and enables improved tracking of objects and scene elements. It also has implications for disentangling representation structure and image structure, resulting in more robust representations that generalize better across various downstream visual tasks. The ability to decouple tokens from fixed grid positions is crucial for handling temporal changes in visual data, addressing the limitations of traditional grid-based methods that struggle to maintain consistent object representations as objects move within the image. Therefore, “Off-Grid Video” suggests a more flexible and powerful approach that leverages scene semantics and object dynamics, potentially leading to better performance in various video understanding tasks.

MooG Model#

The MooG model introduces a novel approach to video representation learning by disentangling the representation structure from the inherent grid structure of image data. Instead of relying on fixed grid-based token arrangements, MooG allows tokens to move freely, dynamically associating with scene elements regardless of their spatial location. This allows for more consistent representation of objects even as they move in time. The model achieves this using cross-attention and positional embeddings, facilitating the tracking of scene elements through changes in camera position or object motion. A key strength is its use of a simple self-supervised objective—next frame prediction—to train the model, eliminating the need for extensive labeled data. MooG’s representation outperforms grid-based baselines on various downstream tasks, demonstrating its effectiveness and potential for broader applications in scene understanding. The model’s architecture is recurrent, facilitating processing of video sequences of arbitrary length, enhancing its adaptability to diverse real-world scenarios. However, further research is warranted to explore scenarios where object content vanishes and reappears, which presents limitations to the current design.

Downstream Tasks#

The paper evaluates a novel video representation model, MooG, on various downstream tasks to demonstrate its effectiveness. The choice of tasks is crucial, showcasing MooG’s ability to handle both dense and object-centric predictions. Point tracking, a task requiring precise temporal correspondence, highlights MooG’s capacity for tracking scene elements through time. Depth estimation, a dense prediction task, assesses MooG’s ability to reconstruct scene geometry, while object tracking, a more complex task involving semantic understanding, tests its object-centric representation capabilities. The quantitative results, comparing MooG against both grid-based and domain-specific baselines, reveal its competitive performance, particularly in the zero-shot transfer settings, which indicates strong generalizability. The selection of tasks and their evaluation metrics thus effectively demonstrates MooG’s capacity for diverse vision applications and its potential to surpass traditional grid-based approaches.

Qualitative Results#

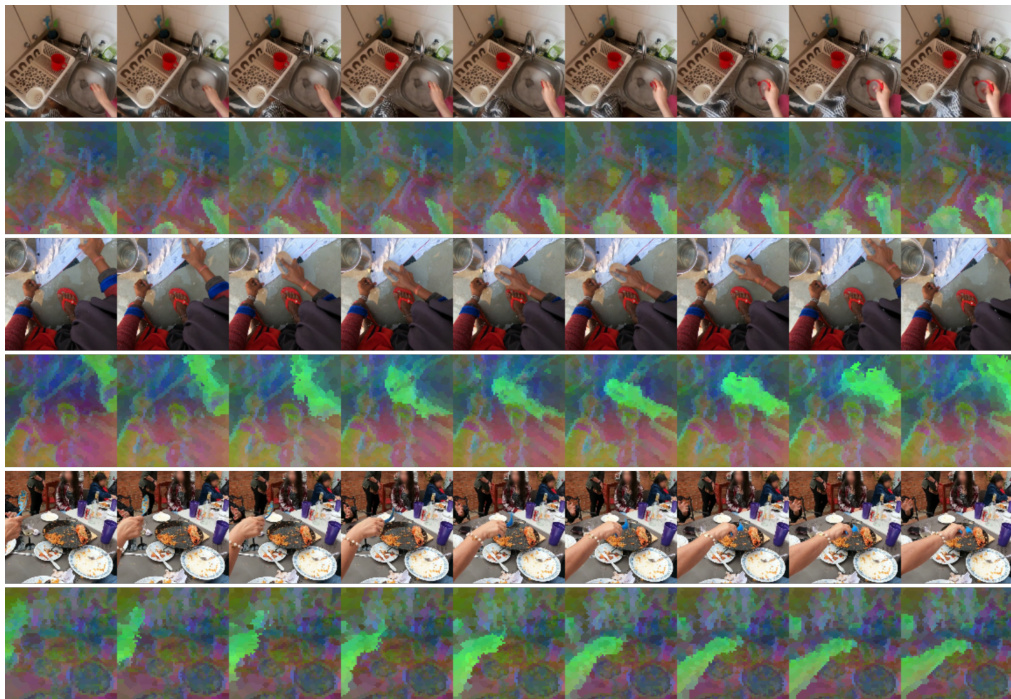

A qualitative analysis of a research paper’s findings focuses on non-numerical observations to understand the nature of the results. It delves into the meaning and implications of the data, moving beyond simple statistics. In a video representation model, qualitative results might involve visualizing attention maps to show which parts of the video a model focuses on. This provides insight into how the model processes information, revealing patterns of attention that may not be evident in quantitative metrics. Additionally, a qualitative evaluation could include showing sample video reconstructions to assess the visual quality and fidelity of the model’s representations. This would highlight any artifacts or distortions. The interpretation of these qualitative observations needs to be thorough and insightful, linking the visual representations to the underlying mechanisms of the model. For example, consistent tracking of objects in video would demonstrate the model’s ability to maintain coherent representations across time. Overall, a good qualitative analysis provides a deeper understanding of the research, making it more persuasive and impactful by illustrating the capabilities of the model.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore MooG’s potential in more complex scenarios, such as handling occlusions and long-term temporal dependencies more effectively. Investigating its ability to generalize to diverse datasets and its scalability to higher resolutions and longer video sequences would be valuable. Combining MooG with other techniques, for instance, incorporating 3D information or leveraging object-centric approaches, could lead to even more robust and informative video representations. A deeper investigation into the interpretability and explainability of MooG’s learned features is crucial, particularly understanding the relationship between learned tokens and scene elements. Furthermore, exploring alternative self-supervised objectives beyond next-frame prediction and adapting MooG for different downstream tasks beyond the ones studied (point tracking, depth estimation, object tracking) would greatly expand its application potential. Finally, evaluating its efficiency and scaling properties compared to other methods on various hardware platforms would be a key area for improvement.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the architecture of the MooG model, a recurrent transformer-based video representation model. The model predicts a future state based on the past state and the current observation. The current observation is encoded and cross-attended to using the predicted state. During training, the model reconstructs the current frame using the predicted state, minimizing the prediction error. The key innovation is that the learned representation allows tokens to ‘move off the grid,’ disentangling the representation structure from the image structure and enabling consistent representation of scene elements even as they move across the image plane through time. The figure shows the process unrolled through time, highlighting the iterative prediction and correction steps.

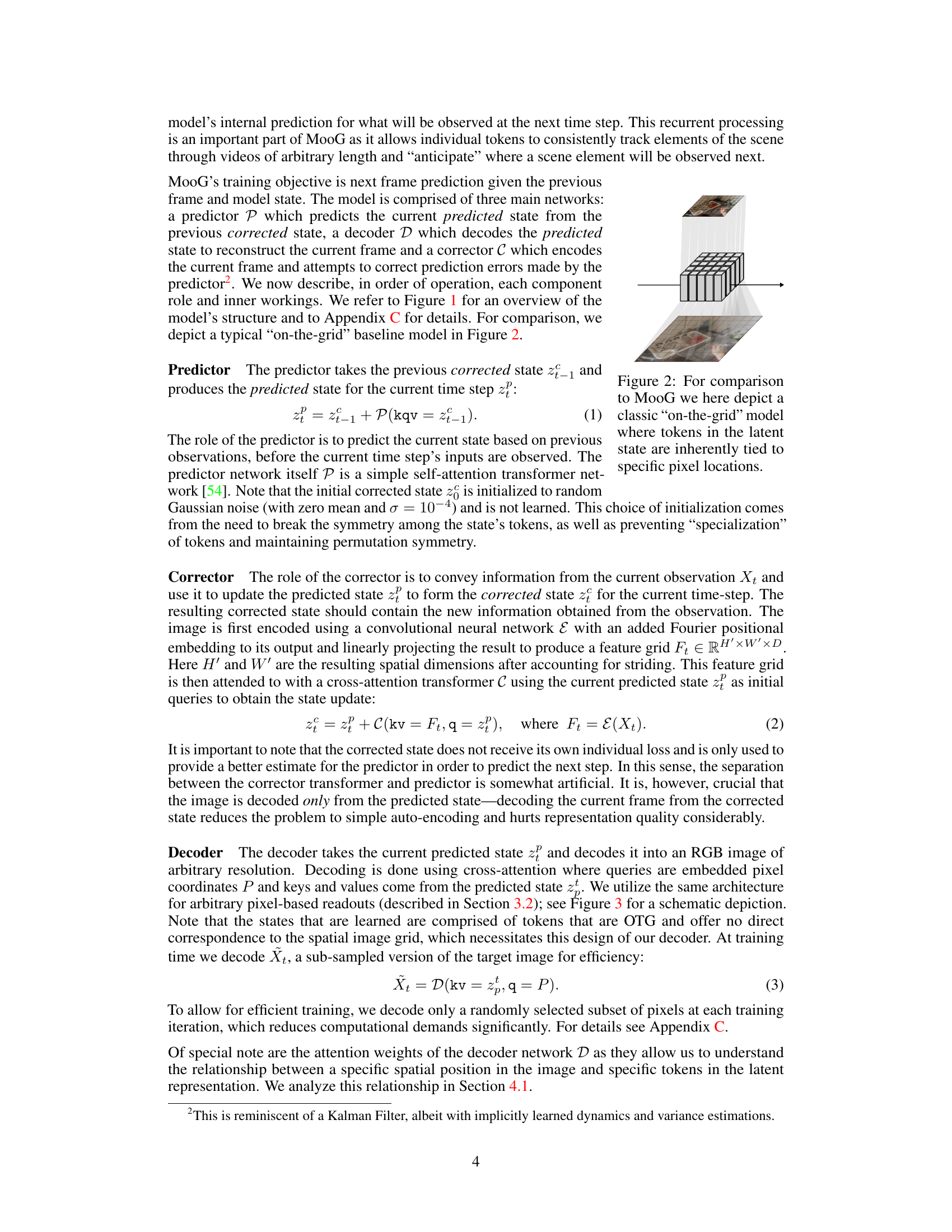

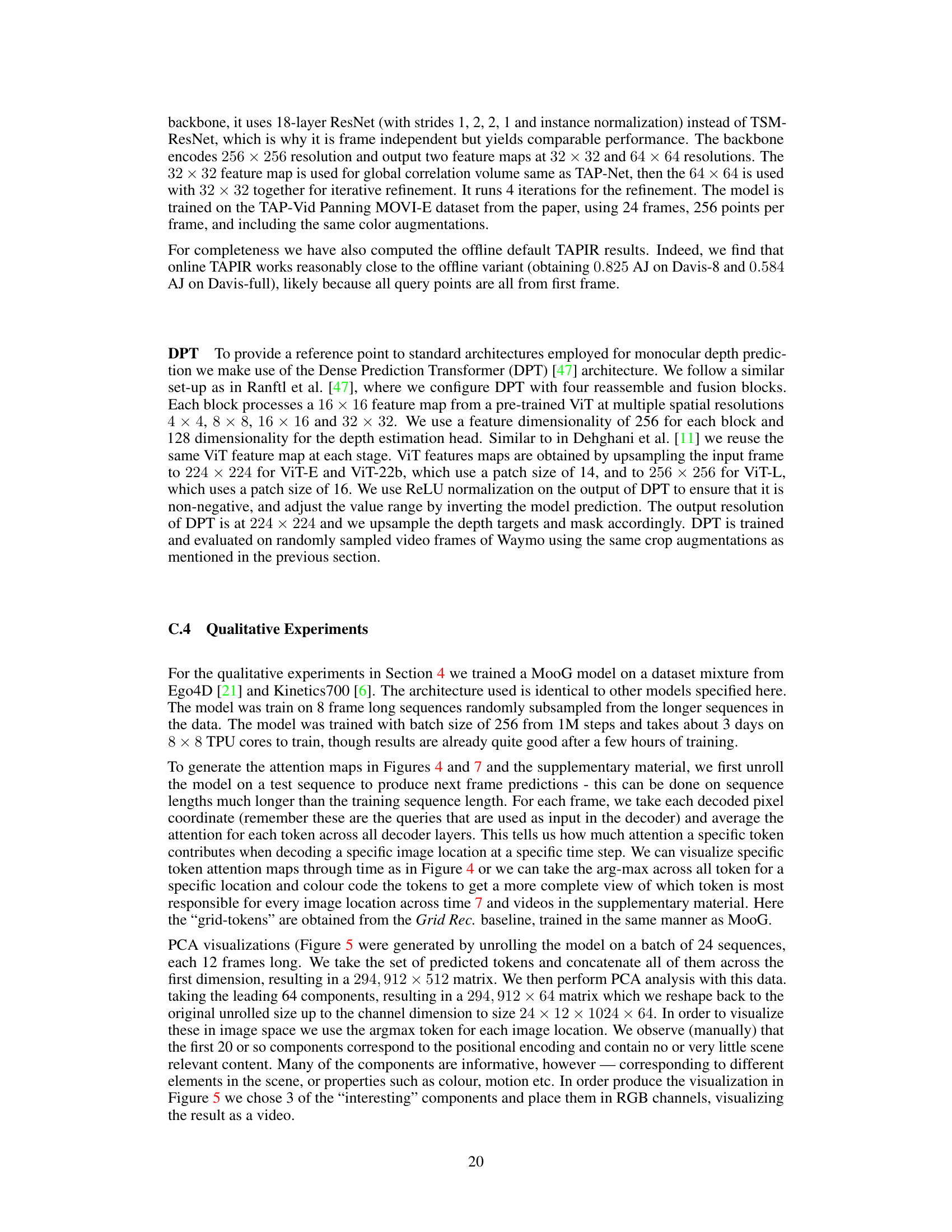

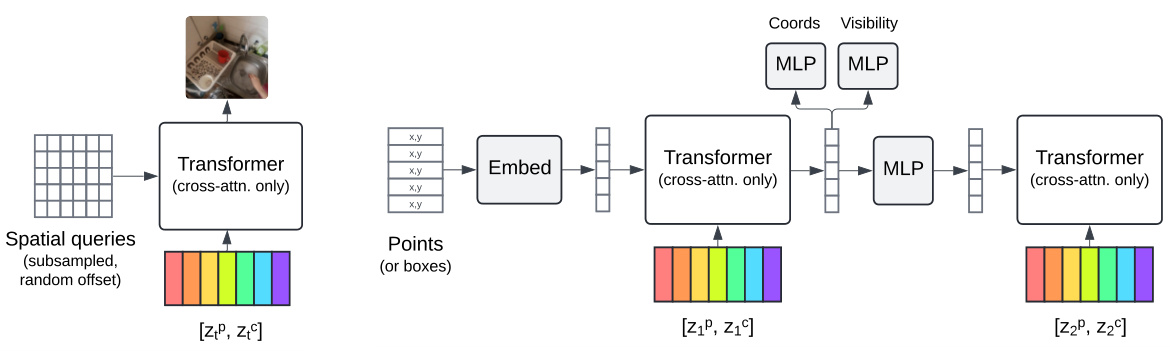

This figure illustrates the two types of readout decoders used in the MooG model for different downstream tasks. Grid-based readouts, such as for pixel-level predictions (e.g., RGB or depth), utilize a simple per-frame cross-attention mechanism with spatial coordinates as queries. In contrast, set-based readouts, like those for point or box tracking, employ a recurrent architecture to maintain consistency over time. The recurrent architecture processes sequences of queries, updating latent representations with cross-attention, before finally decoding into the desired outputs (points or boxes).

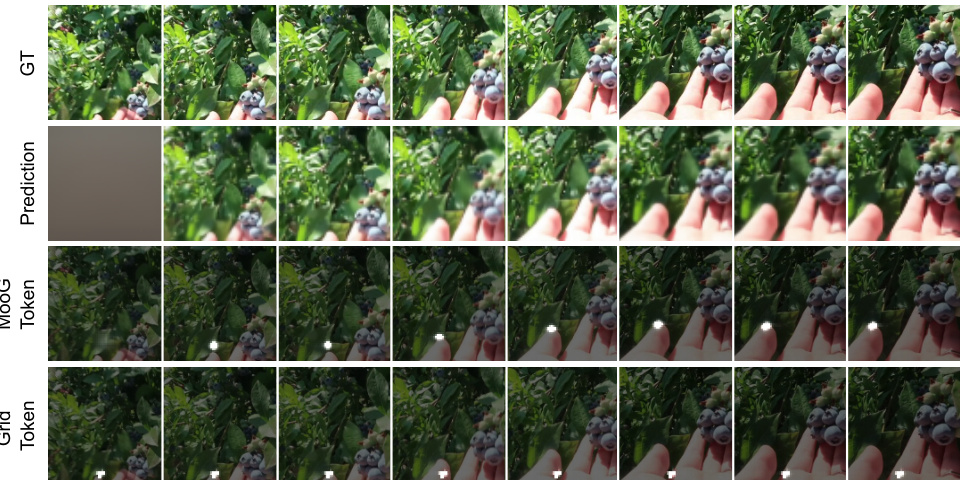

The figure shows a qualitative comparison of MooG and a grid-based baseline on a video sequence. It illustrates how MooG’s off-the-grid tokens consistently track scene elements through motion, while the grid-based tokens remain fixed to spatial locations. The figure includes ground truth frames, model predictions, and attention maps highlighting the token-element associations for both methods.

This figure shows a qualitative comparison of MooG’s performance against a grid-based baseline on a natural video sequence. It demonstrates that MooG’s off-the-grid tokens consistently track scene elements across time, even as they move, unlike grid-based tokens which are tied to fixed spatial locations. The top row displays ground truth frames, the second row shows frames predicted by the model, the third row shows MooG token attention maps overlaid on the ground truth frames, and the bottom row shows the attention maps from a grid-based baseline.

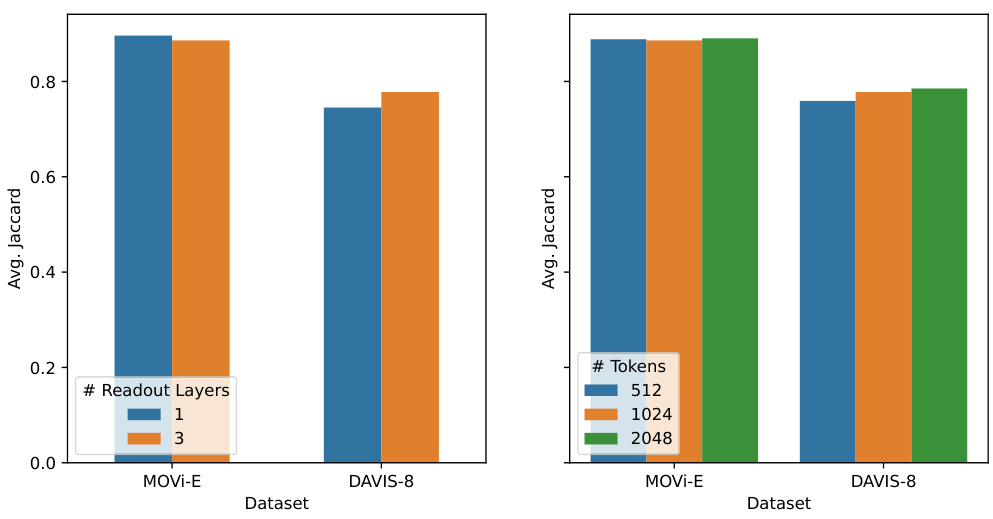

The left bar chart shows the effect of varying the number of readout layers in the decoder on the end-to-end point tracking task. The right chart demonstrates the impact of altering the number of tokens in the MooG model on the same task. Both charts display results for the MOVi-E and DAVIS-8 datasets, allowing for a comparison of performance across different model configurations and datasets.

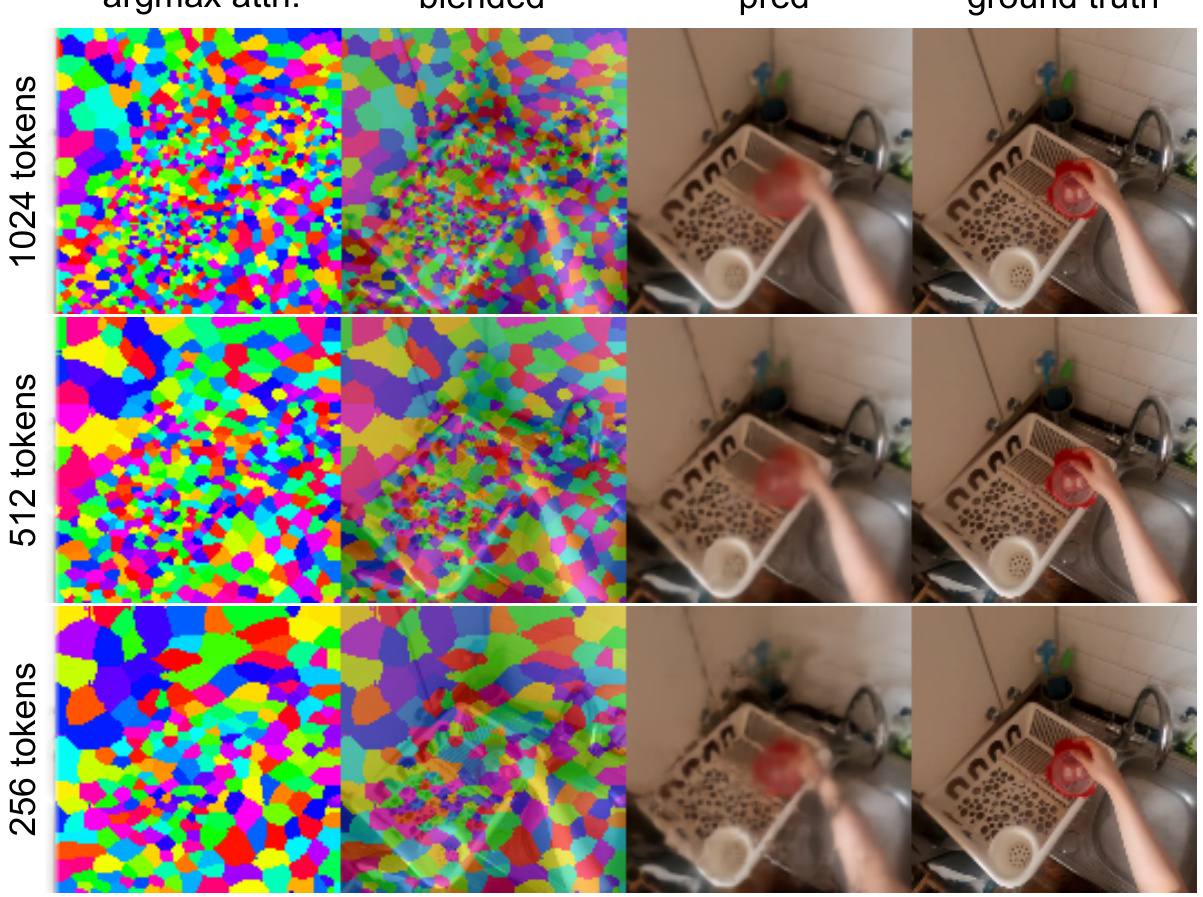

This figure shows the flexibility of MooG to adapt to different numbers of tokens. Three versions of the model, each using a different number of tokens (256, 512, and 1024), were tested on the same video sequence. The results demonstrate that the model successfully predicts future frames even when the number of tokens is changed, showcasing its adaptability and robustness. When using fewer tokens, each token represents a larger portion of the image.

More on tables

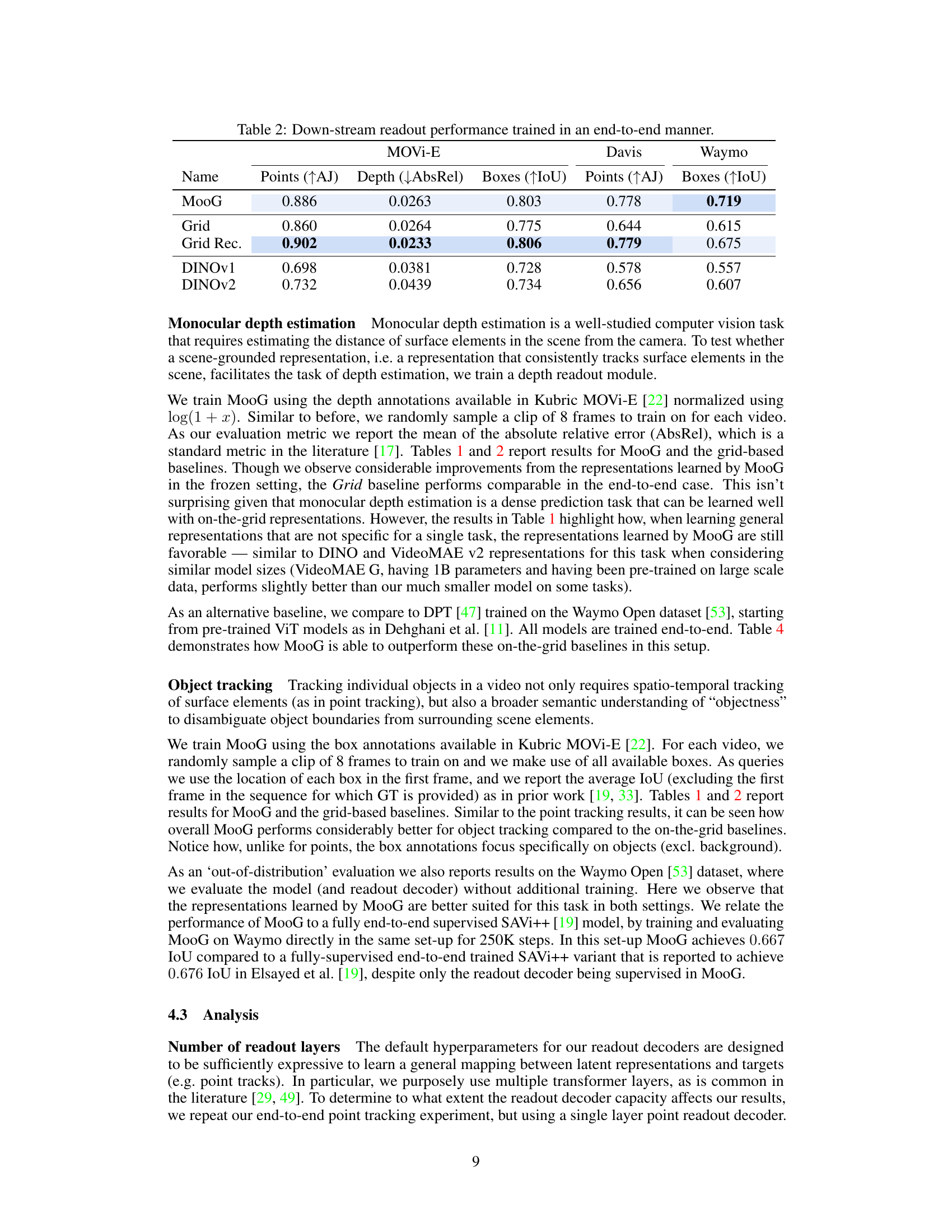

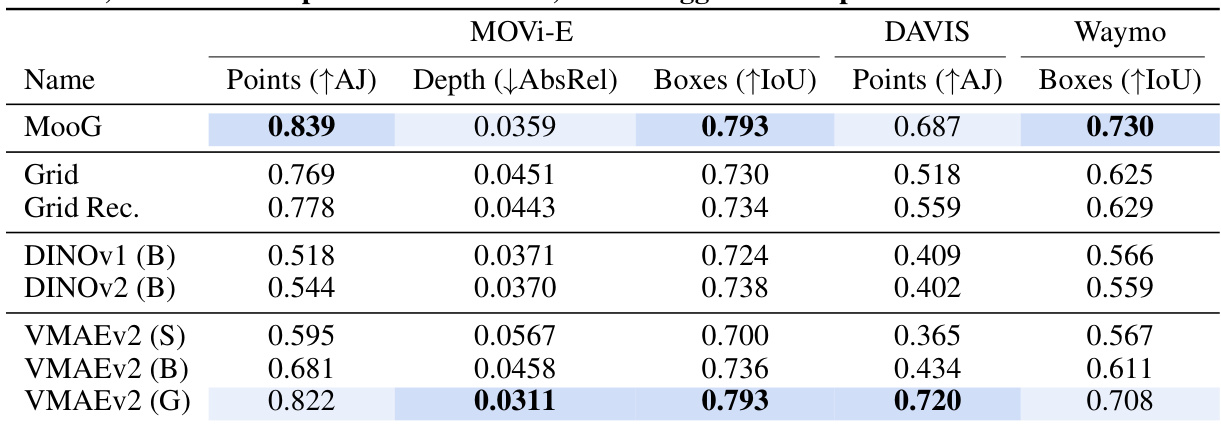

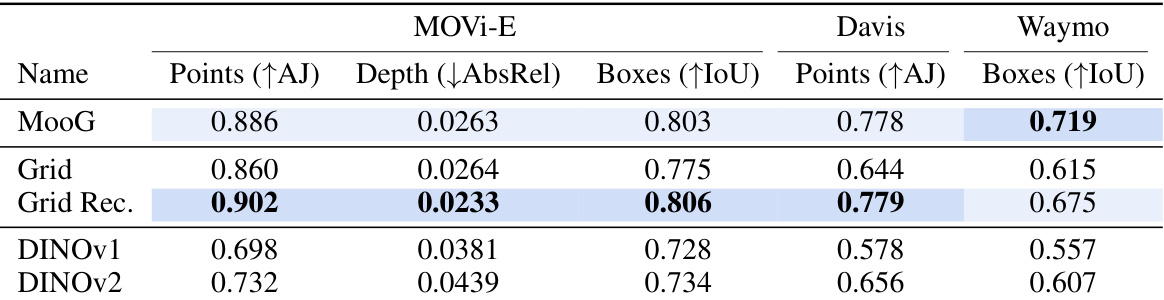

This table presents the quantitative results of different models on three downstream tasks: point tracking, depth estimation, and object tracking. The models were trained end-to-end, meaning the readout decoder was trained alongside the main model. The results are shown for three datasets: MOVi-E, Davis, and Waymo, each using different metrics appropriate for the specific task. The table allows a comparison of MooG against several grid-based baselines (Grid, Grid Rec., DINOv1, DINOv2) highlighting MooG’s improved performance.

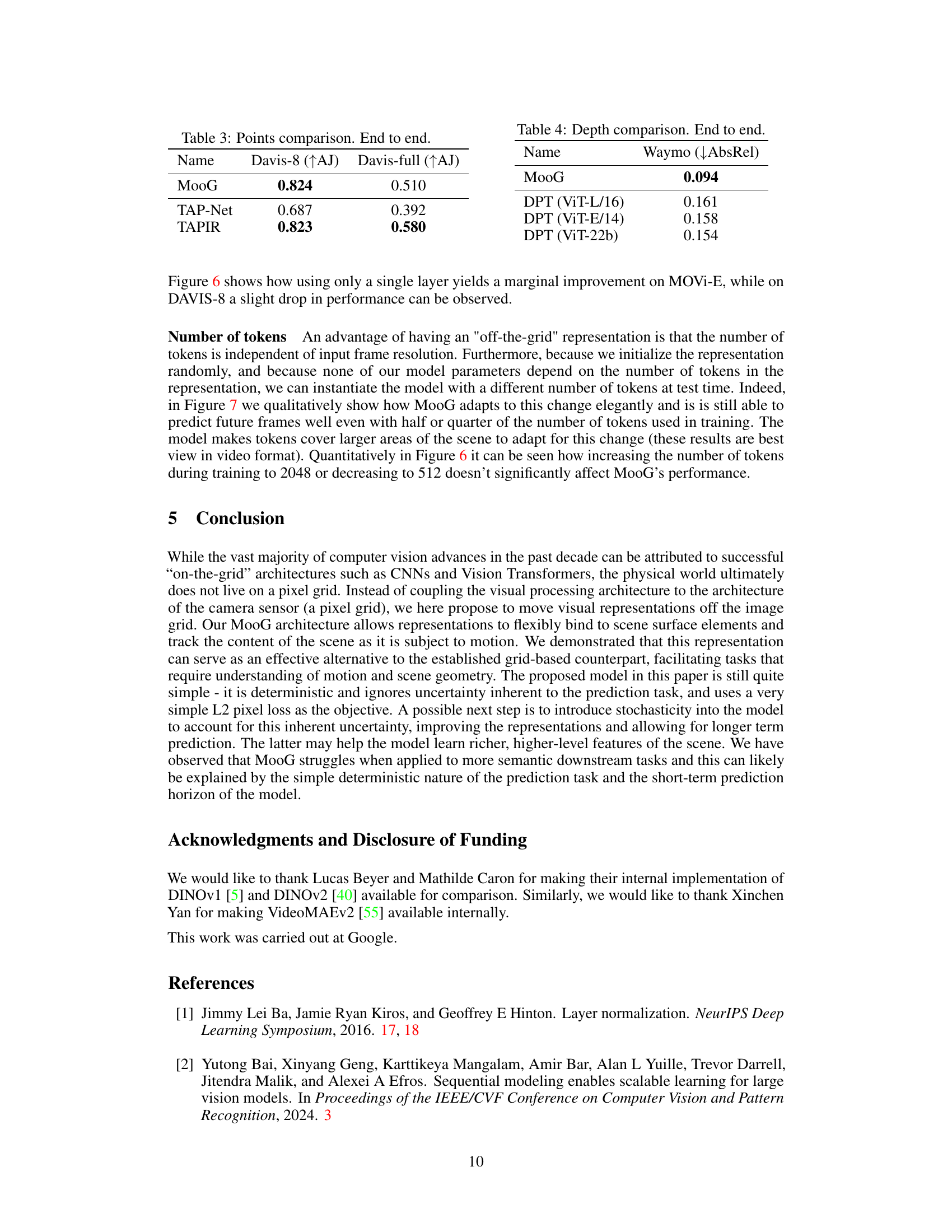

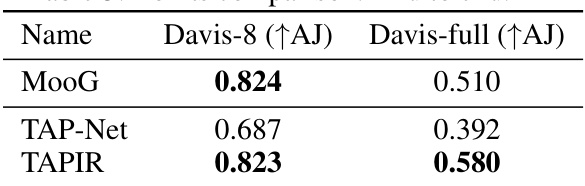

This table presents a comparison of the performance of MooG and other methods on the point tracking task, specifically using the Davis dataset. The comparison is broken down for sequences of 8 frames and for full sequences. The methods compared include MooG, TAP-Net, and TAPIR. The metric used is the average Jaccard index (AJ), which measures the accuracy of point tracking, considering both occlusion and positional errors.

The table compares the performance of MooG and several baselines on three downstream tasks: point tracking, depth estimation, and bounding box detection. The results are presented using metrics appropriate for each task (Average Jaccard for point tracking, Absolute Relative Error for depth, and Intersection over Union for bounding boxes). The baselines include other self-supervised methods (DINO and VideoMAE) and the capacity of each model is indicated. Note that the MooG model uses substantially fewer parameters than the larger baselines, suggesting it is more efficient.

This table shows the quantitative results of different models on three downstream tasks: point tracking, depth estimation, and bounding box prediction. The results are obtained using frozen representations, meaning the pre-trained weights of the models were not updated during the downstream task training. The table compares MooG against various grid-based baselines (Grid, Grid Rec., DINOv1, DINOv2, VideoMAEv2), highlighting the performance differences across different datasets (Waymo, MOVi-E, DAVIS). The model sizes are noted for easier comparison.

This table presents the performance of different models on downstream tasks using frozen representations. It compares MooG against grid-based baselines (Grid, Grid Recurrent, DINOv1, DINOv2, VideoMAEv2) and indicates the size of the Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder used for each baseline. Note that the MooG model is significantly smaller than the largest baselines.

This table presents the quantitative results of different downstream tasks using frozen representations. It compares the performance of MooG against various grid-based baselines (Grid, Grid Rec, DINOv1, DINOv2, VideoMAE v2) across three datasets (Waymo, MOVi-E, DAVIS). The performance metrics used vary depending on the task (Average Jaccard for points, Absolute Relative error for depth, and Intersection over Union for bounding boxes). The table also notes the approximate number of parameters in each model’s encoder to provide context for the comparison.

Full paper#