↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) systems like RNN-Transducer and Attention-based Encoder-Decoder (AED) face challenges in aligning audio and text sequences, leading to complex models and slow processing. RNN-T uses dynamic programming for alignment, while AED uses cross-attention during decoding. These methods demand significant computational resources and complex training procedures.

This paper introduces the “Aligner-Encoder” model, which leverages the self-attention mechanism of transformer-based encoders to perform alignment internally. This simplifies the model architecture and training process, eliminating the need for dynamic programming or extensive cross-attention. The model achieves results comparable to state-of-the-art systems but with significantly reduced inference time – twice as fast as RNN-T and sixteen times faster than AED. The authors also show that the audio-text alignment is clearly visible in the self-attention weights of a certain layer, demonstrating a novel “self-transduction” mechanism within the encoder.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it simplifies the complex process of sequence transduction in automatic speech recognition. It introduces a novel model that is both more accurate and computationally efficient than existing methods. The method is easier to implement, opening new avenues of research and leading to more efficient speech recognition systems.

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the difference in information flow between traditional encoders (used in CTC, RNN-T, and AED) and the proposed Aligner-Encoder. Traditional encoders process audio frames and produce audio-aligned embeddings that are then passed to the decoder. In contrast, the Aligner-Encoder internally performs text alignment during the forward pass, resulting in text-aligned embeddings that are fed to the decoder. This difference is visually represented by the different directions of the arrows.

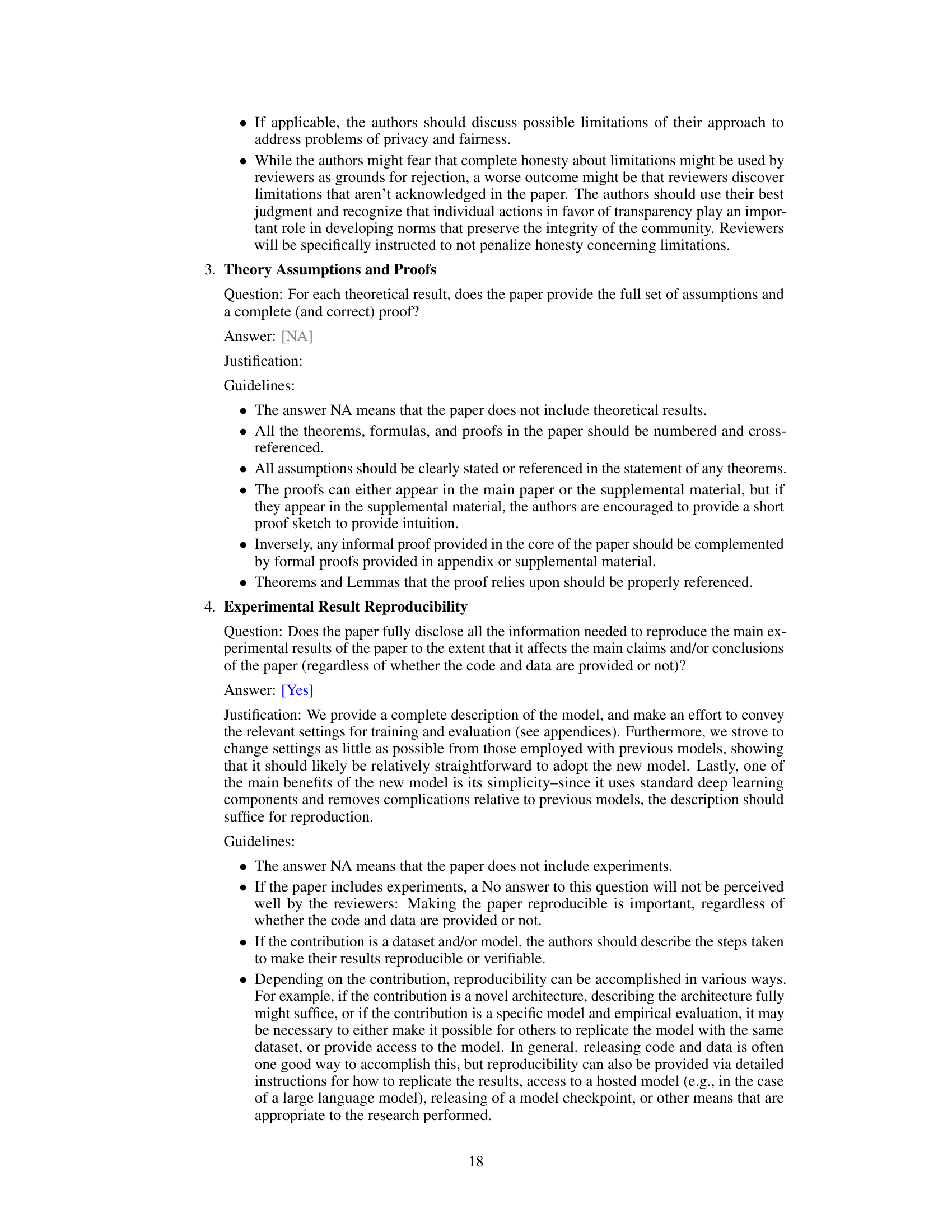

This table shows the settings used for each dataset in the experiments. It includes the number of log-mel features, 2D convolutional layers, encoder dimension, number of encoder layers, number of encoder parameters, LSTM size, and vocabulary size for LibriSpeech, Voice Search, and YouTube datasets.

In-depth insights#

Self-Transduction#

The concept of “Self-Transduction,” while not explicitly a heading in the provided text, represents a core idea within the research paper. It describes a novel phenomenon where a transformer-based encoder, unlike traditional models, performs audio-to-text alignment internally during the forward pass, prior to decoding. This eliminates the need for explicit dynamic programming or full-sequence cross-attention, thus simplifying the overall architecture and improving efficiency. The encoder essentially acts as its own transducer, implicitly performing the alignment function through the learned weights of its self-attention mechanism. This internal alignment process is visualized in the paper by analyzing the self-attention weights, which clearly show the audio-to-text mapping. The self-attention weights reveal a monotonic alignment; this observation suggests a potential for application beyond ASR (Automatic Speech Recognition), particularly in non-monotonic tasks like machine translation or speech translation.

Aligner-Encoder#

The concept of an “Aligner-Encoder” presents a novel approach to sequence transduction tasks, particularly in Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR). It leverages the inherent capabilities of transformer-based encoders to perform alignment implicitly during the forward pass, eliminating the need for explicit dynamic programming or extensive decoding mechanisms as seen in RNN-Transducers or Attention-based Encoder-Decoders. This simplification results in a more efficient and streamlined model architecture. The encoder learns to align audio features with their corresponding text embeddings internally, enabling a lightweight decoder that simply scans through the aligned embeddings, generating one token at a time. This approach offers substantial computational advantages, particularly regarding speed, promising faster training and inference times. While the initial experiments demonstrate performance comparable to the state-of-the-art, further exploration is warranted to fully assess the strengths and limitations in diverse settings, particularly with respect to handling longer sequences and robustness in noisy or low-resource scenarios. The visual representation of audio-text alignment within the self-attention weights of the encoder is a key finding, providing valuable insight into the model’s inner workings and potential for extensions to other sequence transduction problems.

Efficient ASR#

Efficient Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) is a critical area of research, focusing on minimizing computational resources while maintaining accuracy. Reducing computational complexity is paramount, particularly for real-time applications and resource-constrained devices. This involves optimizing model architectures, such as using lightweight neural networks, efficient attention mechanisms, and employing techniques like knowledge distillation. Efficient decoding algorithms are crucial; these reduce latency and resource usage during transcription. Data efficiency is another key aspect, focusing on training accurate models with smaller datasets. Techniques such as data augmentation and transfer learning improve model performance without needing extensive data. Hardware acceleration through specialized processors and optimized software further improves ASR efficiency. Quantization and other model compression methods help reduce model size without significant accuracy loss. Ultimately, the goal of efficient ASR is to achieve a balance between accuracy, speed, and resource usage, making speech technology accessible across various platforms and devices.

Long-Form Speech#

The challenges of handling long-form speech in Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) are significant, as they require models capable of maintaining context and accuracy over extended durations. The paper addresses this by exploring techniques to extend the capabilities of their Aligner-Encoder model beyond its training data limitations. Blind segmentation, a common method, is shown to suffer from errors at segment boundaries, highlighting the need for more sophisticated methods. The proposed solution involves ‘chunking’ the audio and processing it in smaller segments, while preserving context between segments via a clever state-priming mechanism. This approach demonstrates improved performance on long-form speech, showing comparable results to RNN-T while achieving greater efficiency. However, the inherent limitation of the approach is acknowledged: performance degrades with utterances significantly exceeding the training data length, indicating that further investigation and possibly specialized training on long-form data would be beneficial. This highlights that achieving robustness in long-form ASR is an ongoing challenge that warrants further research. While the proposed ‘chunking’ method offers improvement, it is not a complete solution and signifies the importance of contextual handling in long-form speech processing.

Alignment Analysis#

Alignment analysis in sequence-to-sequence models is crucial for understanding how the model maps input and output sequences. Aligning-encoders offer a unique perspective by integrating the alignment process directly within the encoder’s forward pass, eliminating the need for separate alignment mechanisms. This approach simplifies model architecture and improves efficiency. The analysis of self-attention weights reveals clear visualizations of the alignment, indicating where the model effectively links input audio frames with corresponding output text tokens. Analyzing these weights across different layers highlights how alignment emerges gradually, starting with local relationships and eventually developing a global mapping between the input and output sequences. This analysis can reveal limitations, such as the model’s ability to generalize to longer sequences beyond training data. Furthermore, analyzing the alignment process sheds light on the model’s ability to handle non-monotonic alignments. Studying these alignment patterns is key to improving model performance and understanding its internal mechanism.

More visual insights#

More on figures

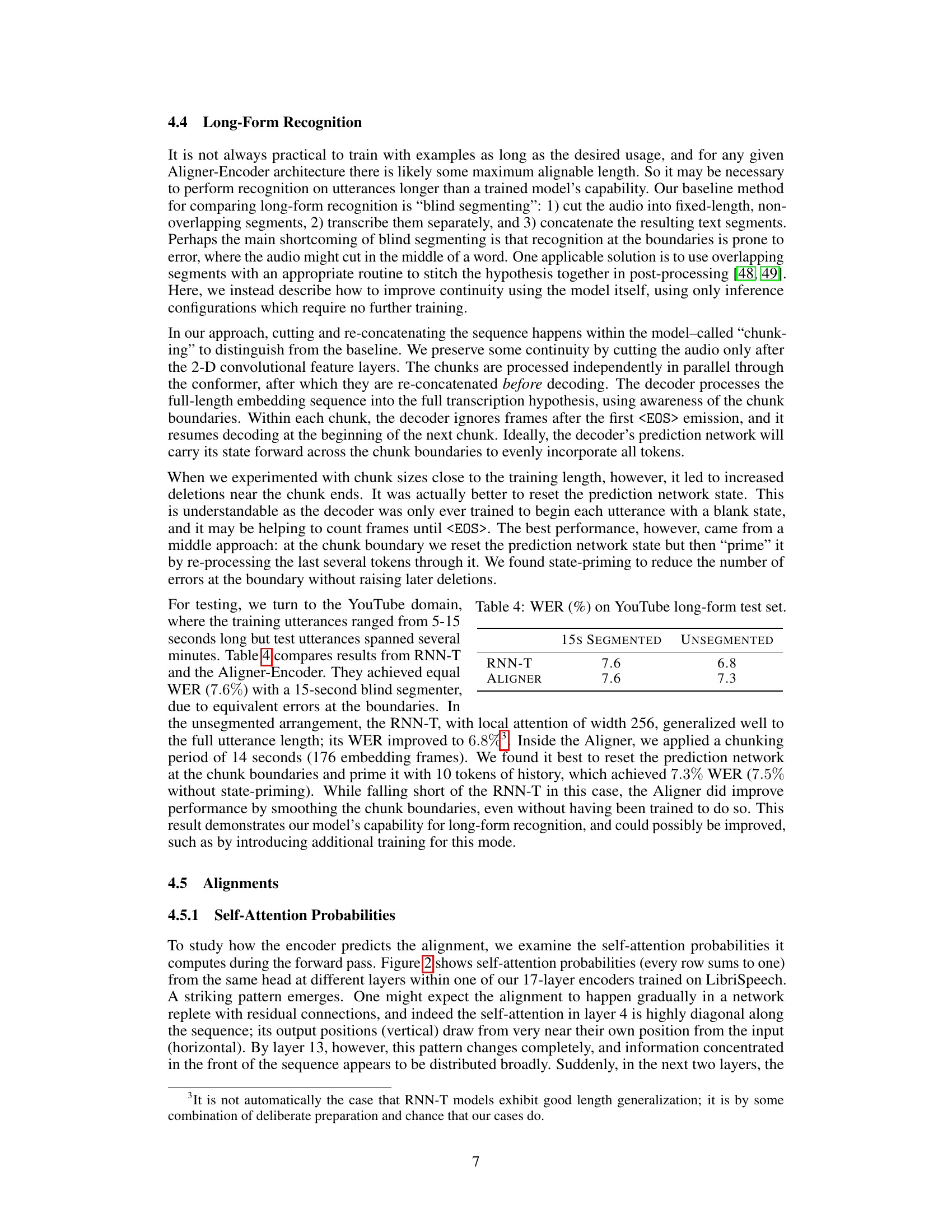

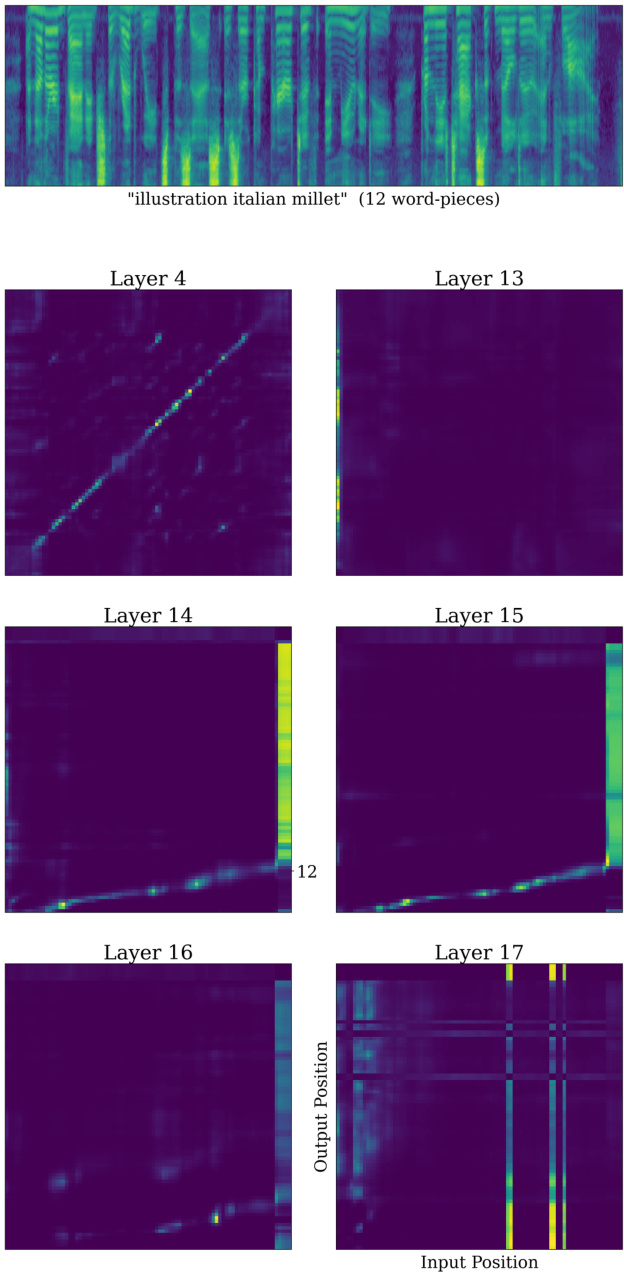

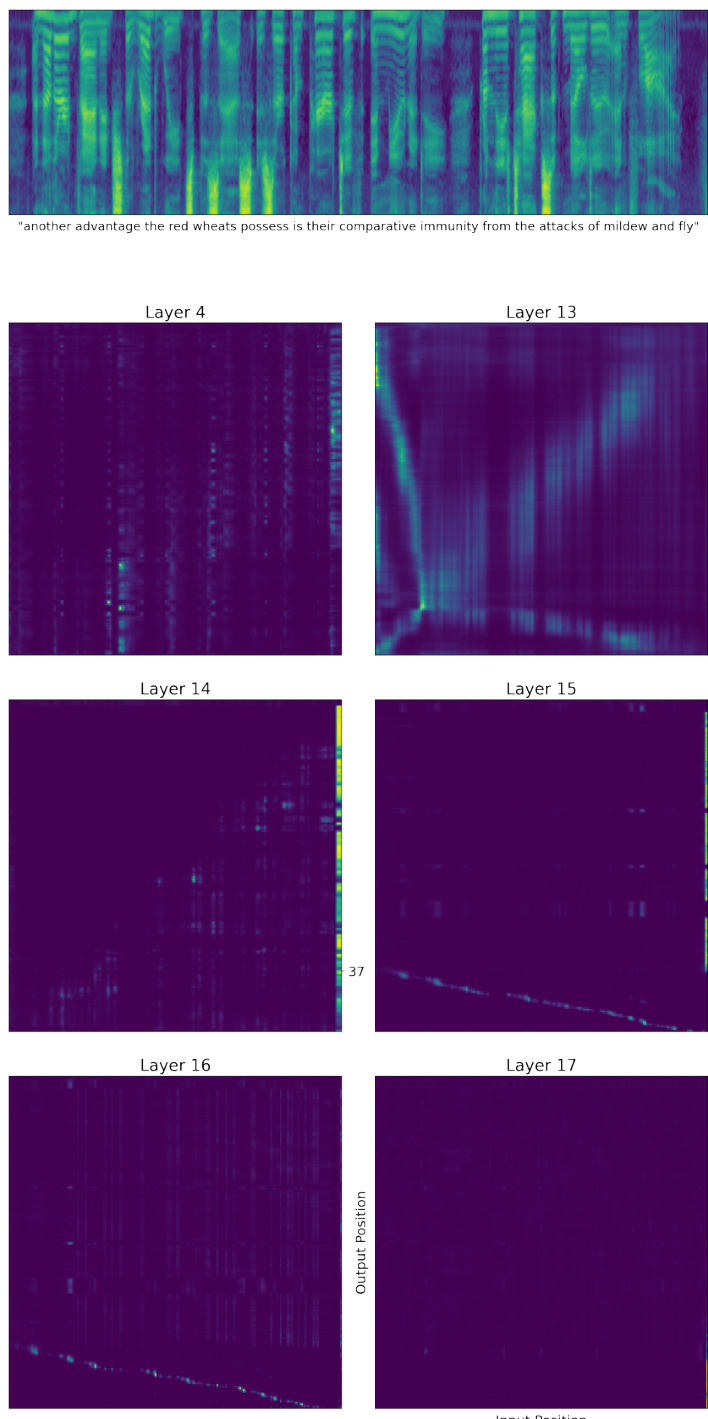

This figure visualizes the self-attention probabilities within a single head across different layers (4, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17) of a 17-layer Aligner-Encoder model. Each subplot represents a layer, showing the attention weights as a heatmap. The x-axis represents the input positions (audio frames), and the y-axis represents the output positions (word-pieces). The heatmap’s intensity indicates the strength of attention between input and output positions. The figure aims to demonstrate how the alignment process evolves across the layers, showing a shift from local to global alignment as the network progresses.

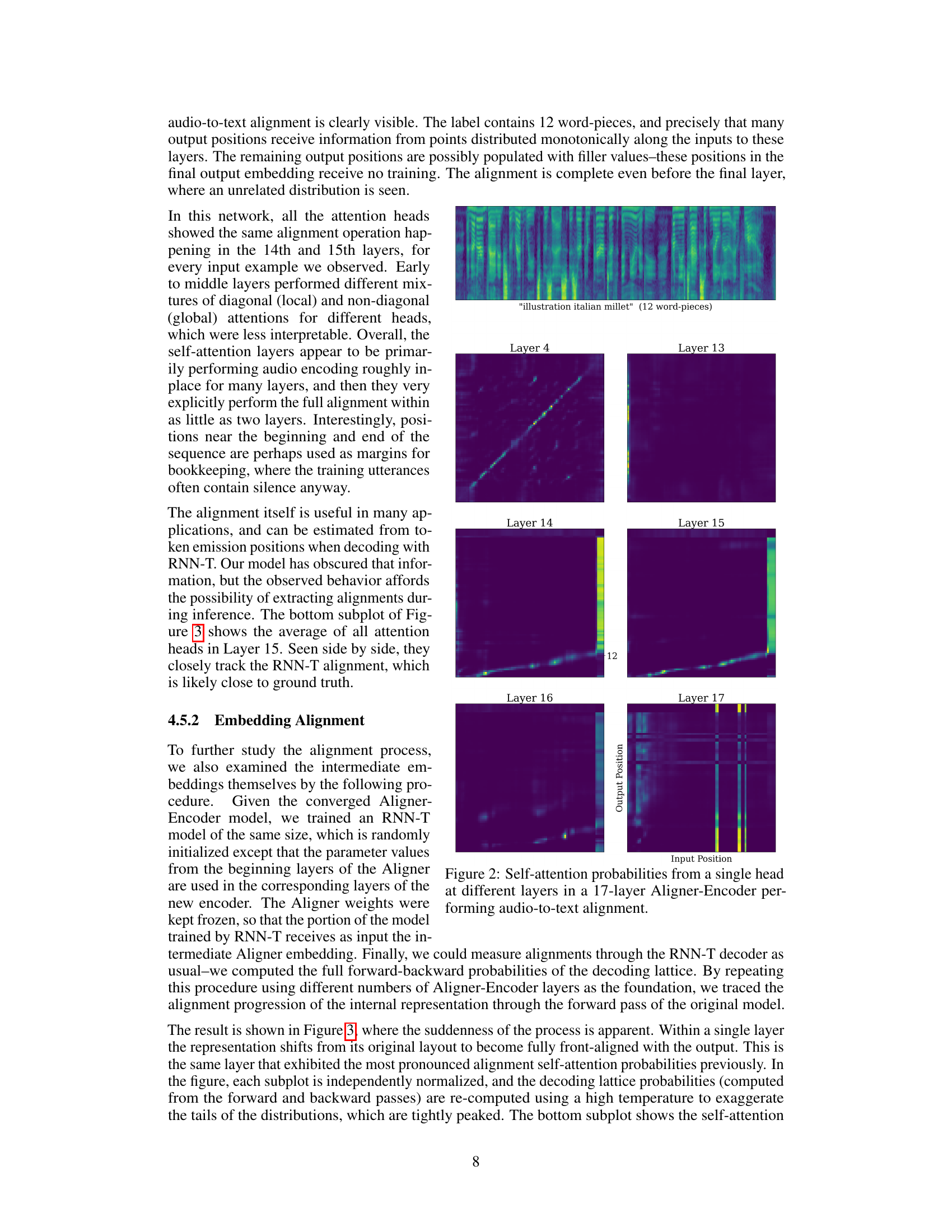

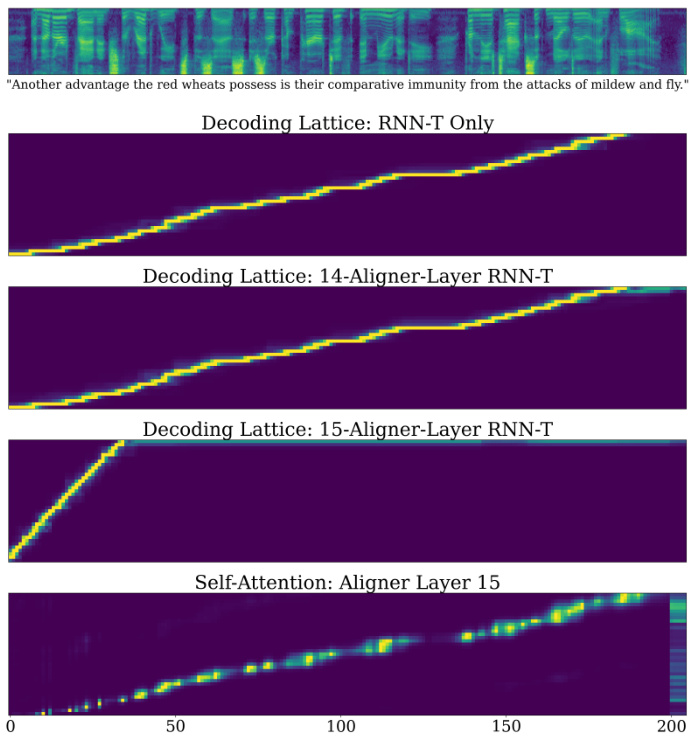

This figure compares the decoding lattice probabilities generated by a standard RNN-T model and two RNN-T models trained on top of Aligner-Encoders with different numbers of layers (14 and 15). It also shows the self-attention weights from layer 15 of the Aligner-Encoder. The comparison highlights how the Aligner-Encoder progressively learns to align audio and text information, with layer 15 showing a clear diagonal alignment pattern in its self-attention weights, indicating a direct mapping between audio frames and output tokens. This contrasts with the more diffuse alignment patterns in the RNN-T models, which need to explicitly use dynamic programming to find the optimal alignment during inference. The figure demonstrates the Aligner-Encoder’s ability to implicitly perform alignment within its encoder, simplifying the overall ASR model.

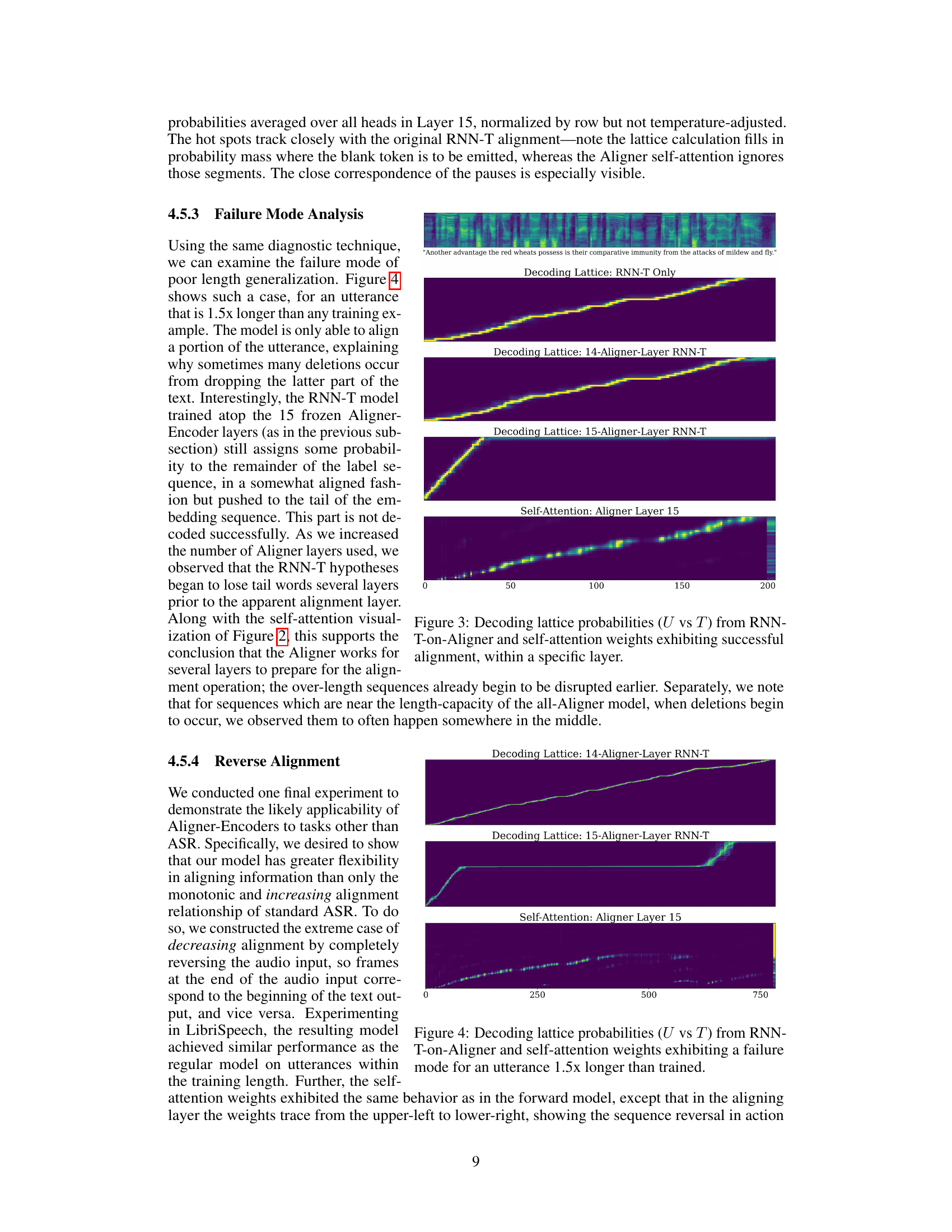

This figure visualizes the alignment process in two different ways. The top two subplots show the decoding lattices generated by RNN-T models trained on top of different numbers of Aligner-Encoder layers. The bottom subplot shows the self-attention weights from the 15th layer of the Aligner-Encoder. These visualizations demonstrate how the Aligner-Encoder gradually learns to align audio and text embeddings, culminating in a clear alignment in the self-attention weights of Layer 15. The successful alignment is indicated by the diagonal concentration of probability mass.

This figure visualizes the self-attention probabilities at different layers of a 17-layer Aligner-Encoder during audio-to-text alignment. Each subplot represents a different layer of the network. The x-axis represents the input positions (audio frames), and the y-axis represents the output positions (text tokens). The color intensity represents the strength of the attention weight between the input and output positions. The figure demonstrates how the alignment is gradually formed from layer to layer, starting with largely local connections and ultimately leading to a monotonic alignment in later layers.

More on tables

This table presents the Word Error Rate (WER) results for different models on the Voice Search dataset, broken down by four subsets: Main Test, and rare-word sets for Maps, News, and Search Queries. The models compared are RNN-T, Aligner, CTC, and Non-AR Aligner. The WER is a metric for measuring the accuracy of Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) systems, with lower values indicating better performance. This table highlights the performance of the Aligner model in comparison to state-of-the-art baselines on a real-world dataset of voice search queries.

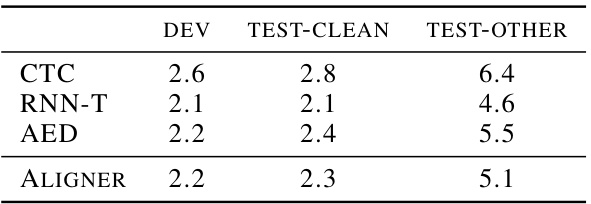

This table presents the Word Error Rate (WER) achieved by different models on the LibriSpeech dataset. The models compared are CTC, RNN-T, AED, and the proposed Aligner model. WER is shown for three subsets of the LibriSpeech test set: DEV, TEST-CLEAN, and TEST-OTHER, representing different levels of difficulty. Lower WER values indicate better performance.

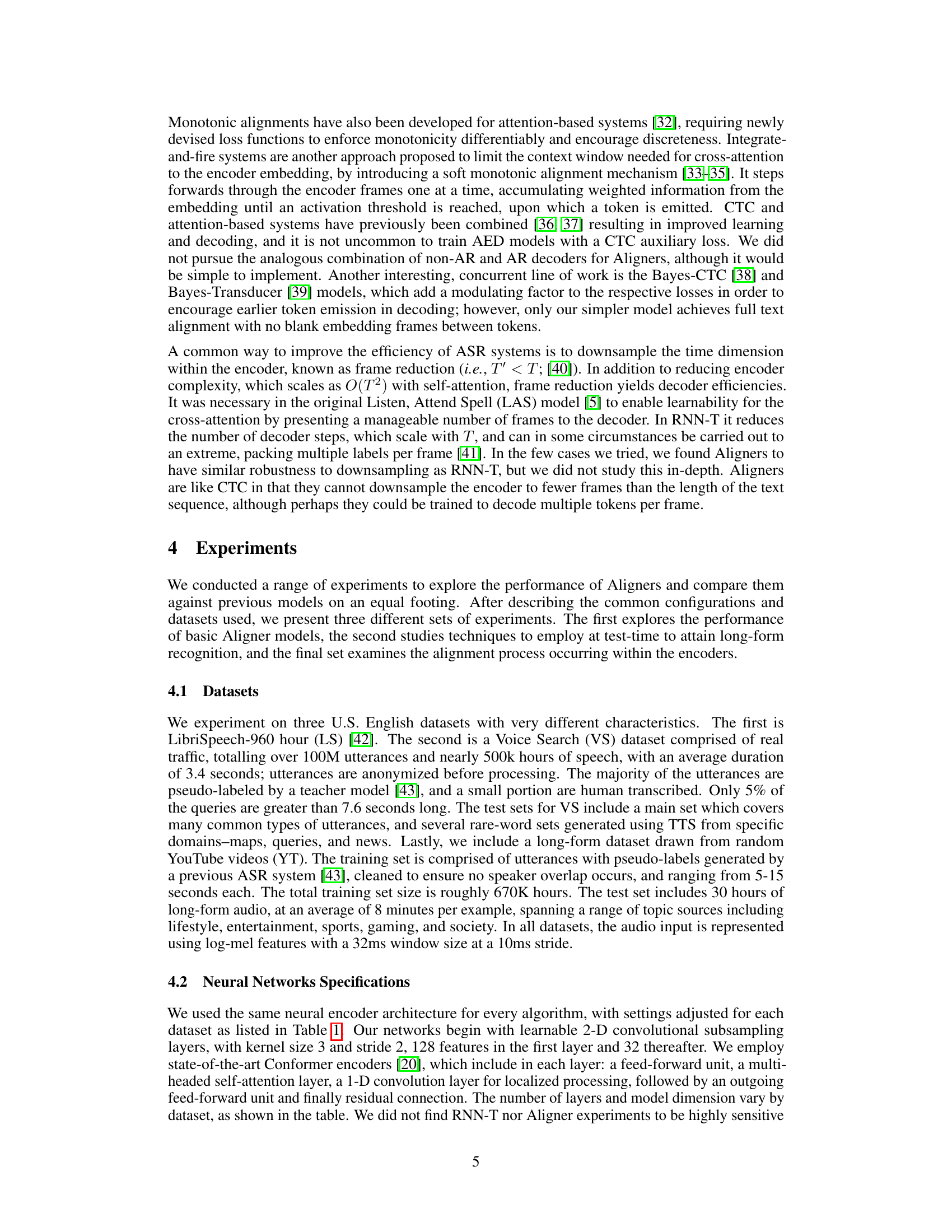

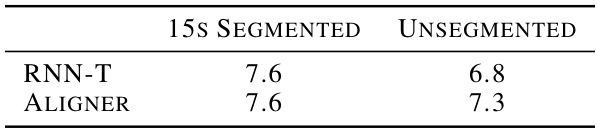

This table presents the Word Error Rate (WER) results for RNN-T and Aligner models on the YouTube long-form test set. It compares the performance of both models using a 15-second segmented approach and an unsegmented approach. The unsegmented approach tests the models’ ability to handle long audio sequences without dividing them into segments. The results show comparable performance (7.6% WER) for both models when using the 15-second segmented approach, but RNN-T shows an improvement in performance with the unsegmented approach (6.8% WER), whereas Aligner still shows acceptable performance with 7.3% WER in the unsegmented setting.

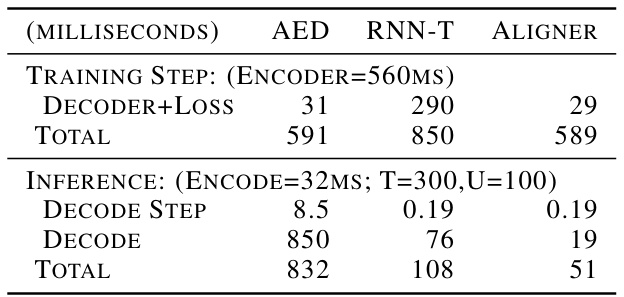

This table compares the training and inference time of three different models (AED, RNN-T, and Aligner) on the LibriSpeech dataset. It shows a breakdown of the computation time during training (including encoder and decoder+loss) and during inference (including encoding and decoding). The Aligner model demonstrates significantly faster inference time compared to the other two models, showcasing its computational efficiency.

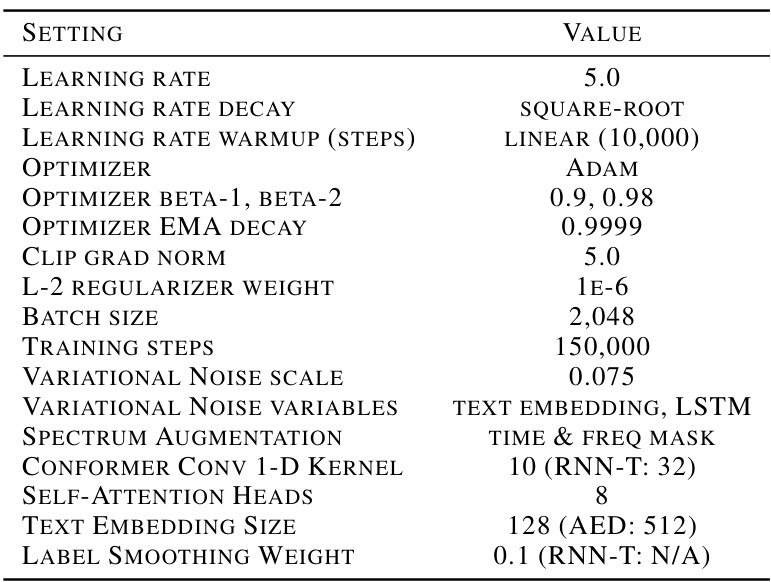

This table lists the common hyperparameter settings used for training the different models (Aligner, RNN-T, AED) on the LibriSpeech dataset. It includes parameters such as learning rate, optimizer, regularization, batch size, and other training details specific to the Conformer encoder architecture used in the experiments. The table helps to clarify the consistency and comparability of the experimental setup across the models.

This table presents the Word Error Rate (WER) results on the LibriSpeech Test-Clean dataset, broken down by utterance length. It compares different ASR models (CTC, RNN-T, AED, Aligner, and their concatenated versions) across three utterance length categories: <17 seconds, 17-21 seconds, and >21 seconds. The table shows that the Aligner model struggles significantly with longer utterances, but this issue is alleviated by concatenating training examples.

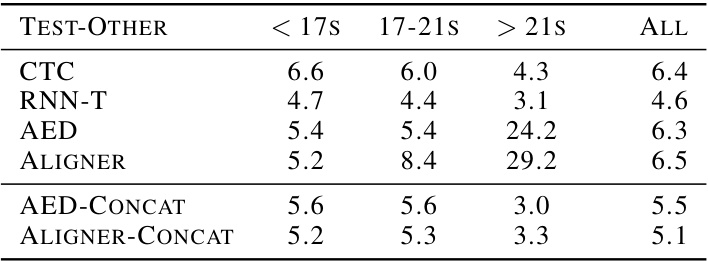

This table presents the Word Error Rate (WER) results for the LibriSpeech Test-Other dataset, broken down by utterance length categories (<17s, 17-21s, >21s). It compares the performance of various models (CTC, RNN-T, AED, Aligner, and their concatenated versions) showing the WER for each category and the overall performance. The concatenation methods aim to improve the performance on longer utterances.

Full paper#