↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Medical image analysis using deep learning faces challenges due to domain shifts—models trained on one dataset often perform poorly on data from different hospitals or demographics. Existing visual backbones lack architectural priors enabling reliable generalization.

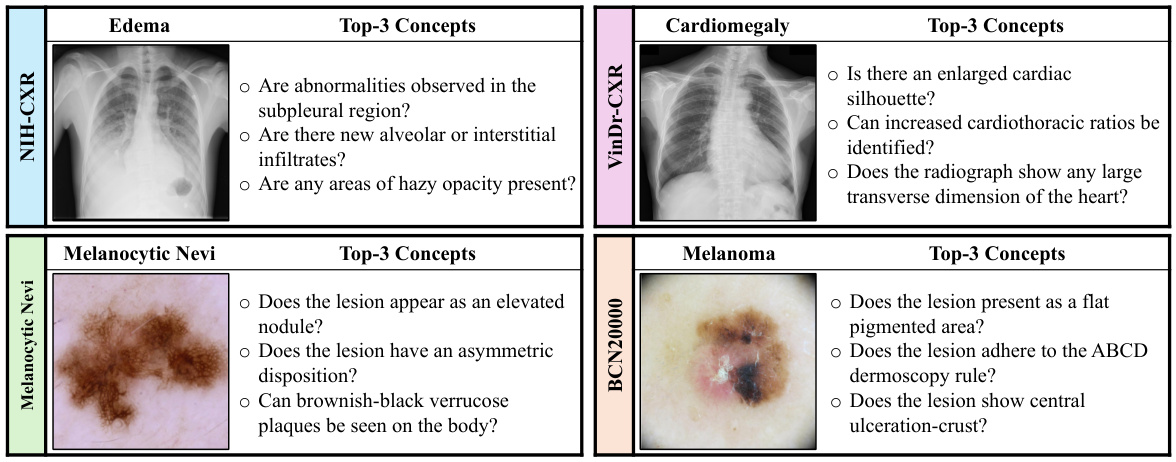

The authors introduce Knowledge-enhanced Bottlenecks (KnoBo), a concept bottleneck model integrating knowledge priors from medical textbooks and PubMed. KnoBo uses retrieval-augmented language models to define clinically relevant concepts and a novel training procedure. Evaluated across 20 datasets, KnoBo significantly outperforms fine-tuned models on confounded datasets, showcasing the efficacy of incorporating explicit medical knowledge to enhance model robustness and generalization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on medical image analysis and domain generalization. It highlights the critical need for incorporating prior knowledge into deep learning models to improve robustness and generalization, particularly in the context of medical imaging where data is scarce and often confounded. The proposed method, KnoBo, offers a practical solution and opens new avenues for future research.

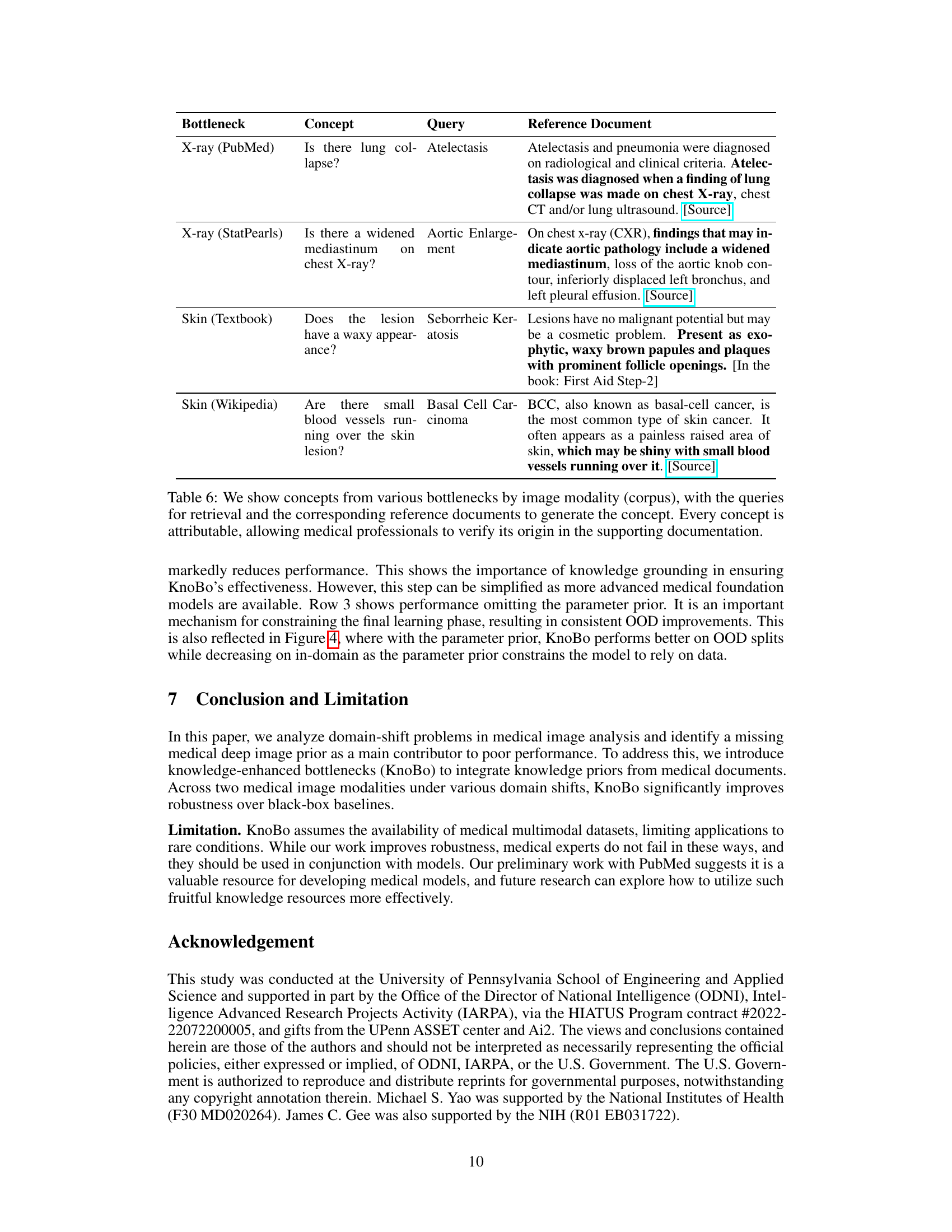

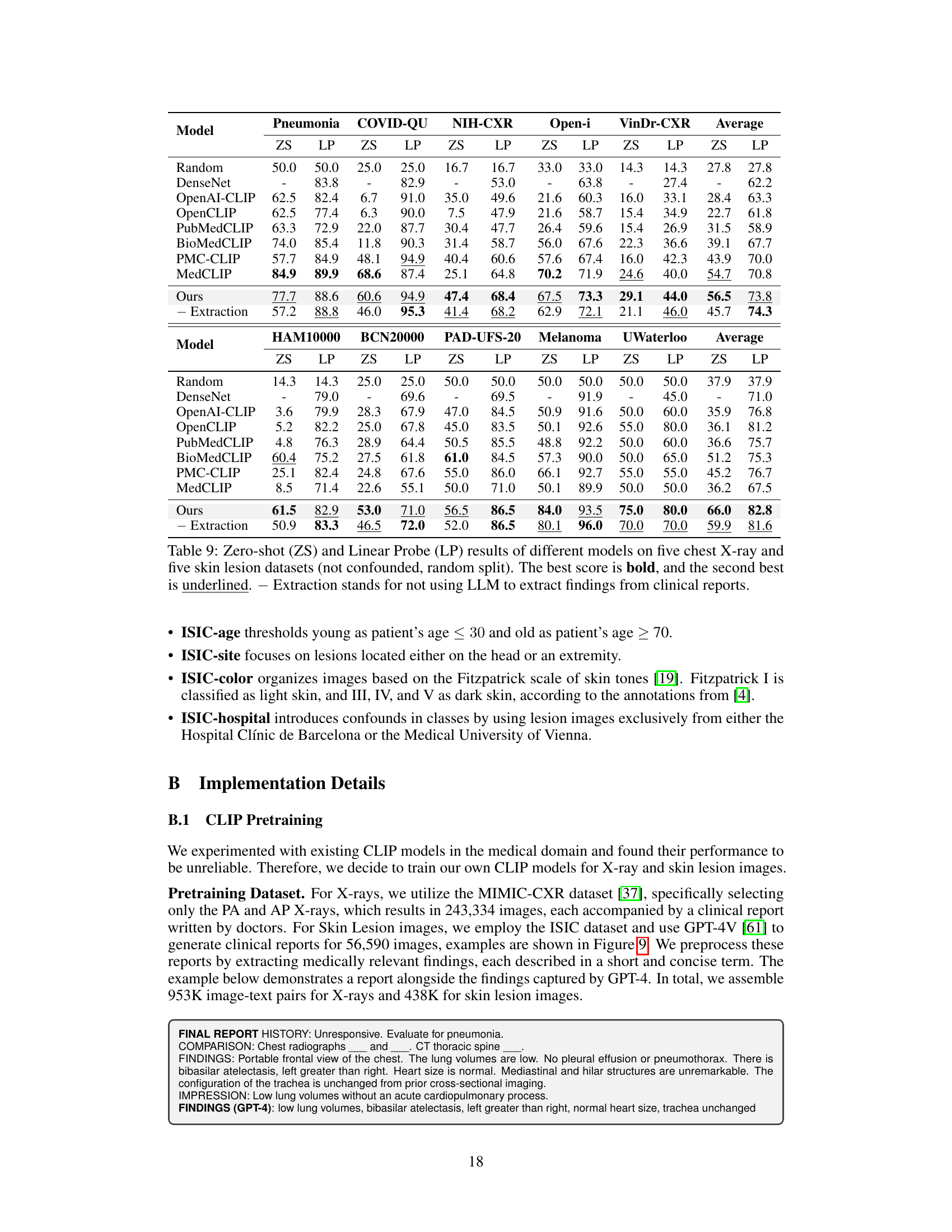

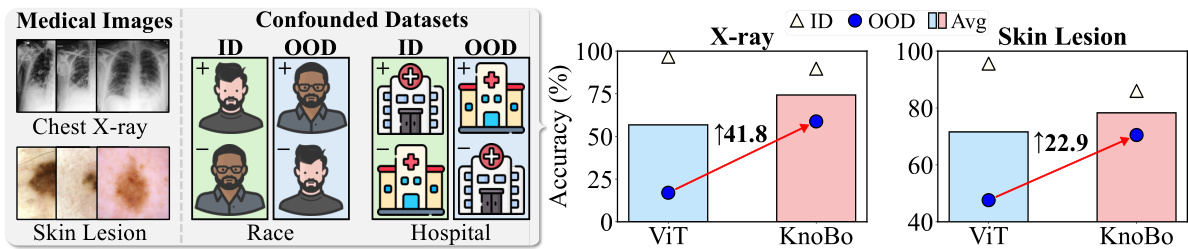

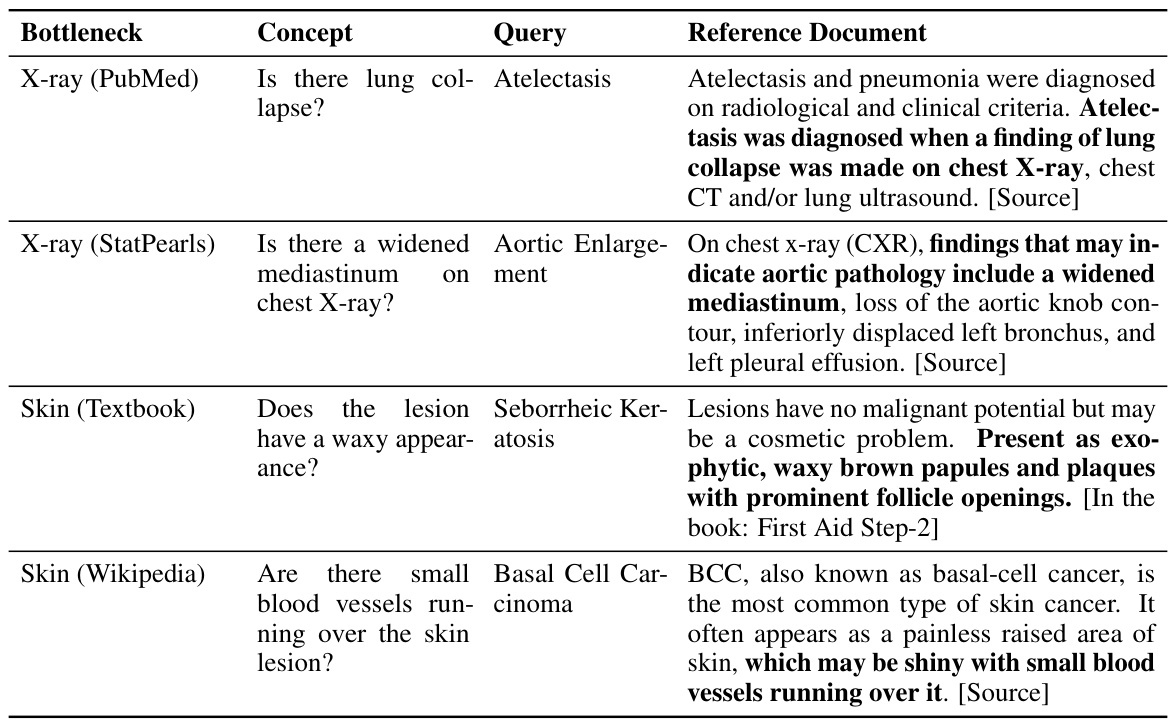

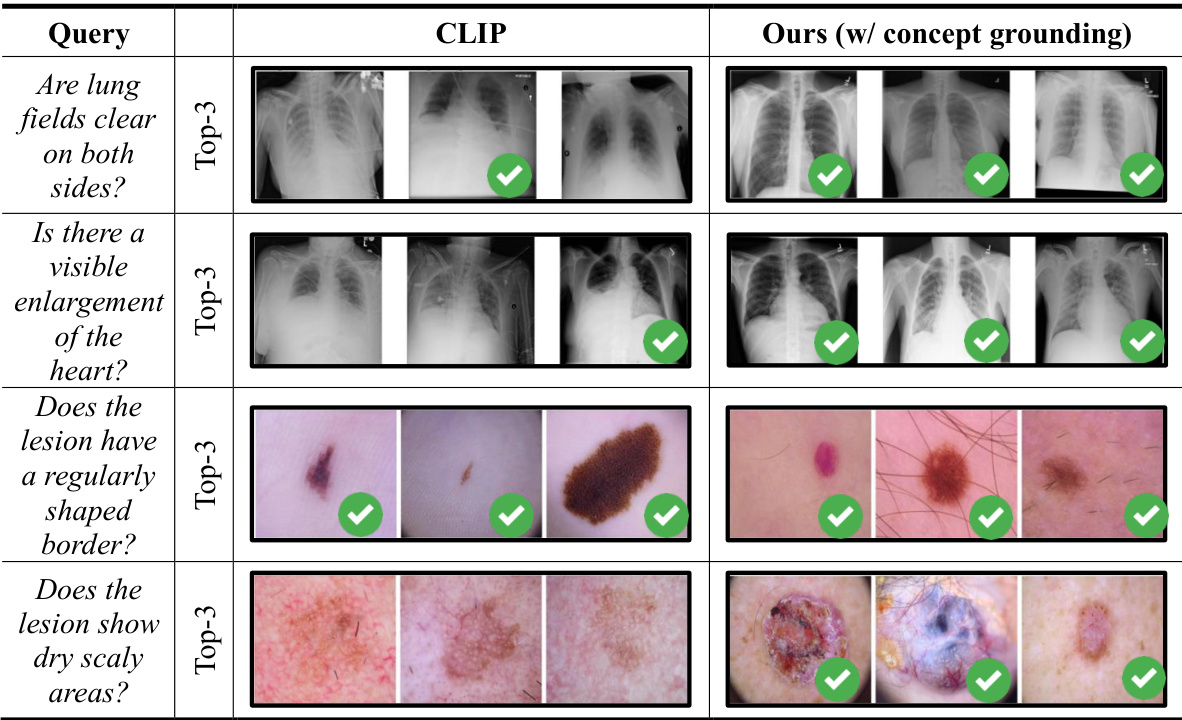

Visual Insights#

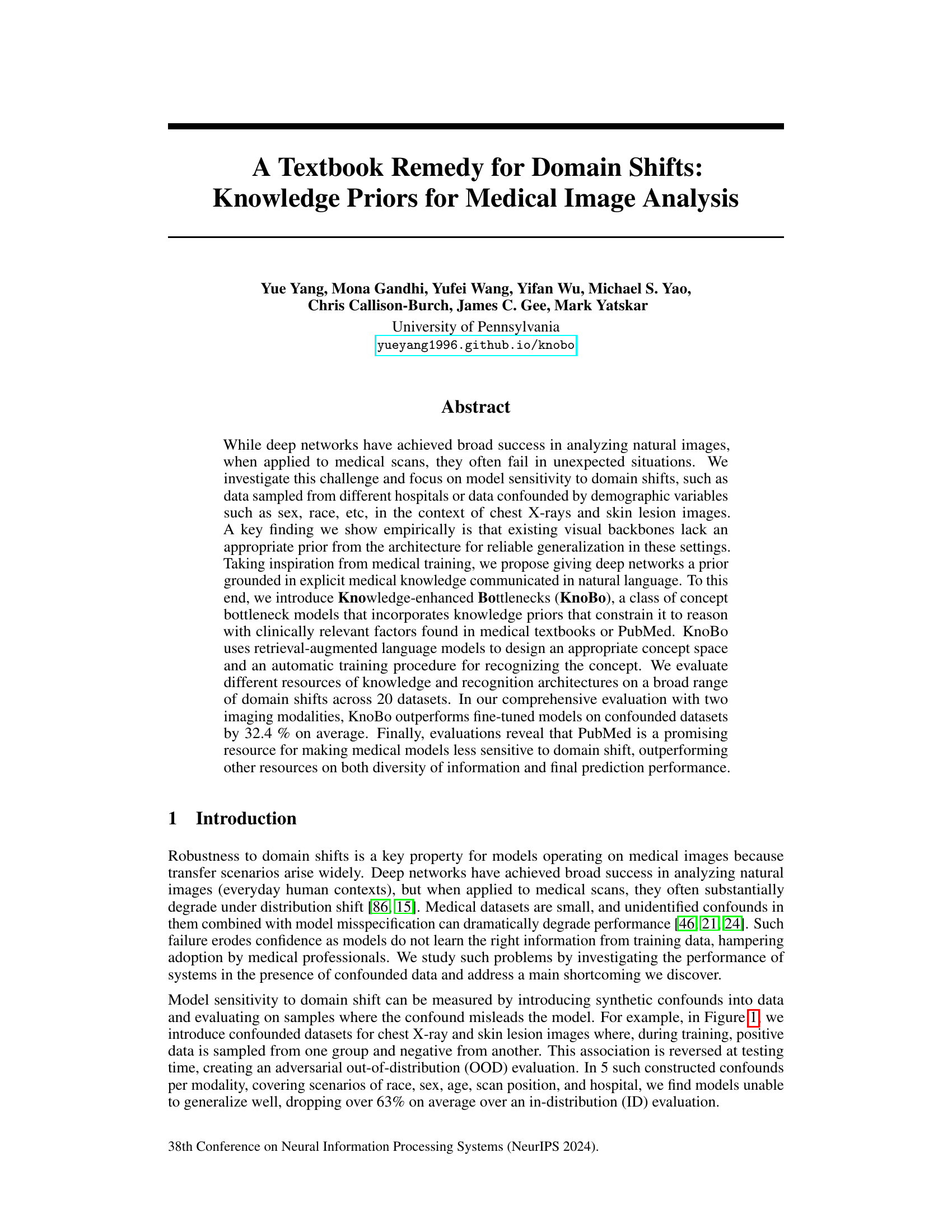

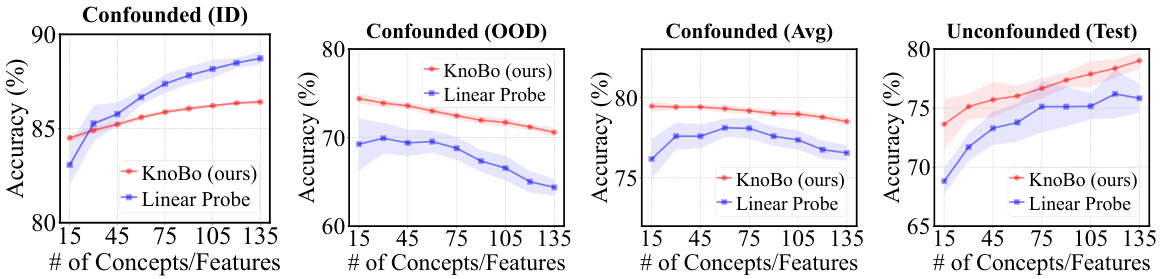

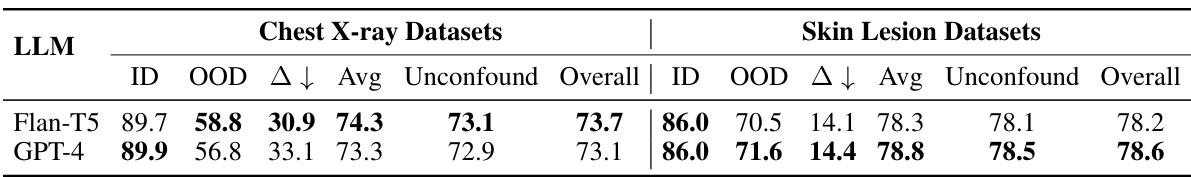

This figure compares the performance of the proposed KnoBo model and a standard vision transformer model (ViT) on in-domain and out-of-domain medical image datasets. The datasets were confounded by introducing demographic variables (race) and environmental factors (hospital) that are not directly relevant to the medical diagnosis. The results show that KnoBo significantly outperforms ViT on out-of-domain data, demonstrating improved robustness to domain shifts.

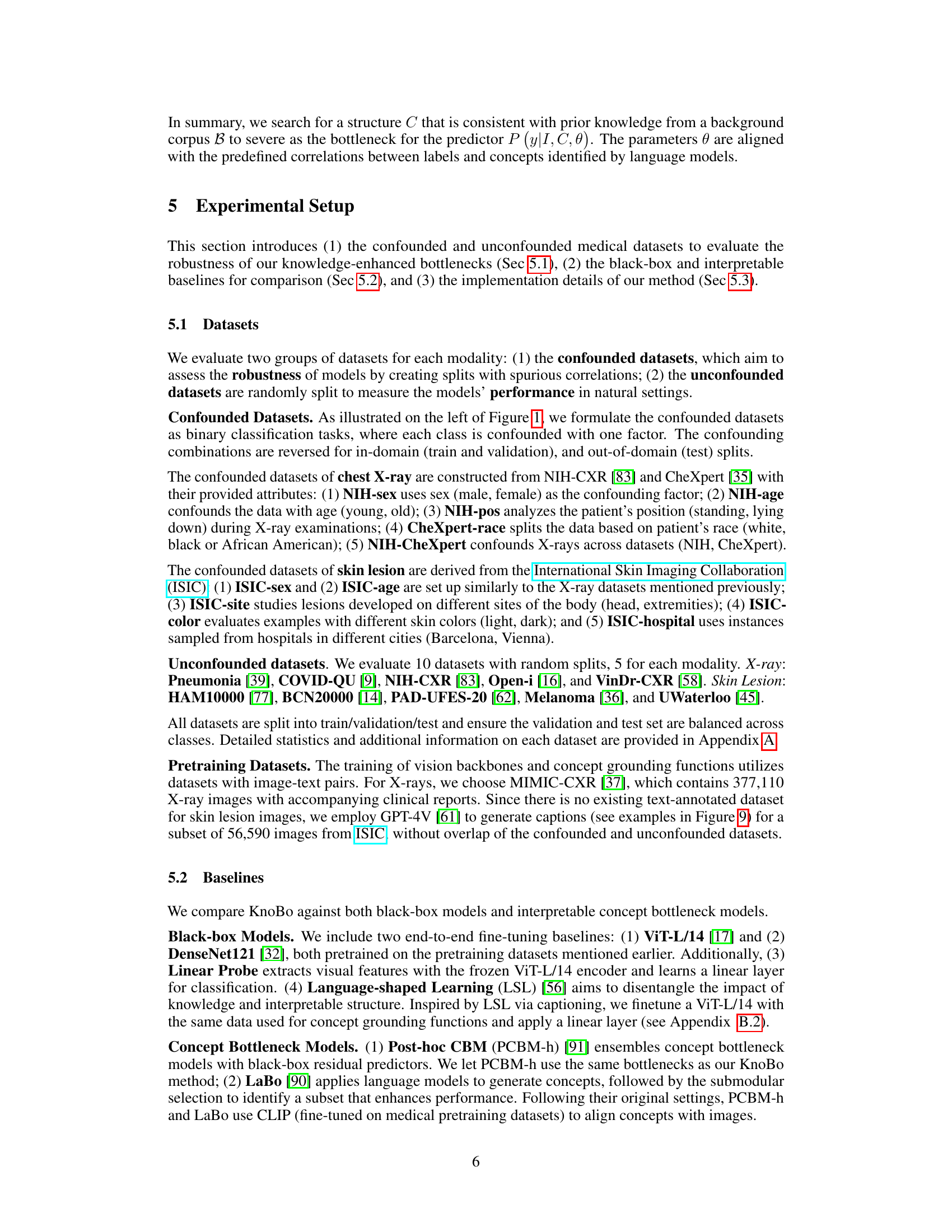

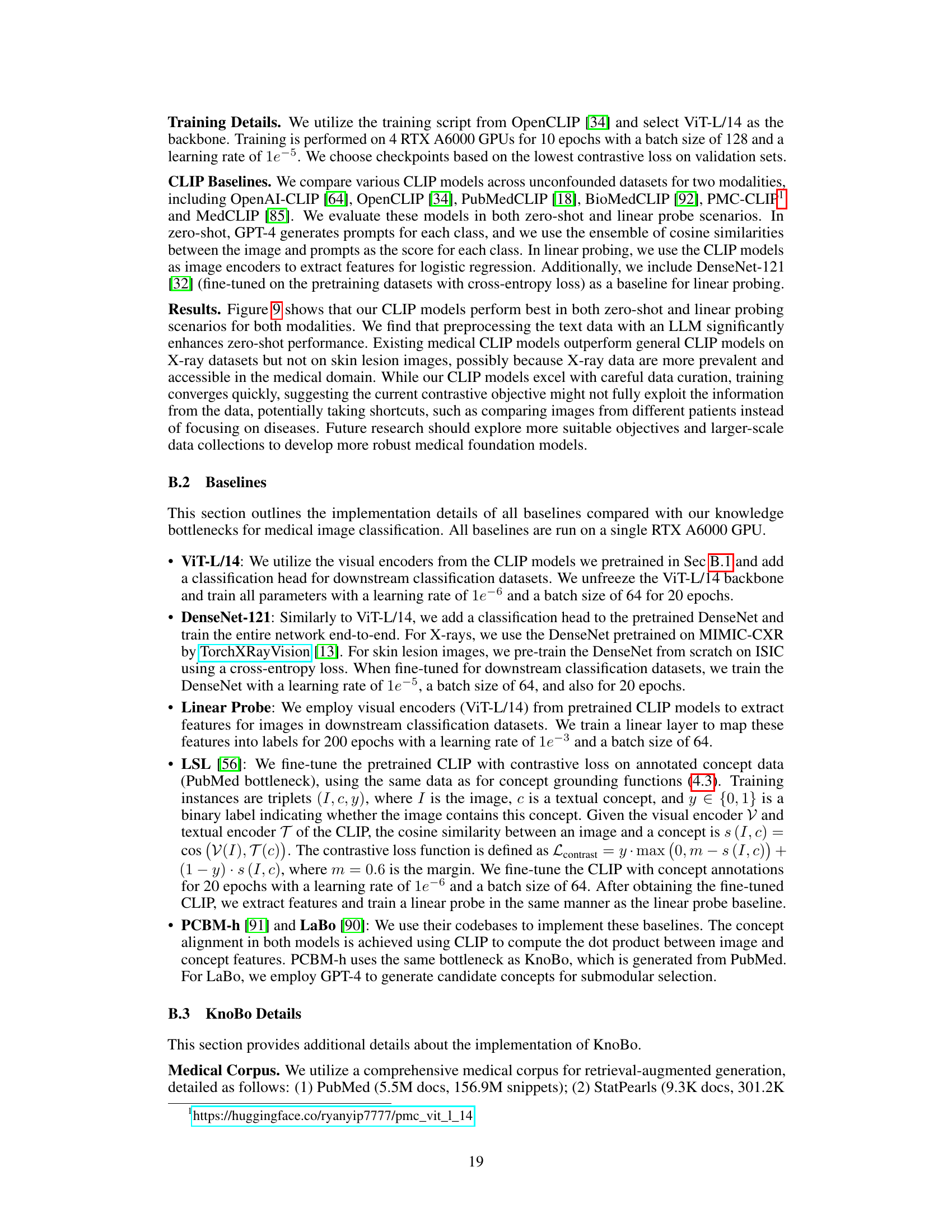

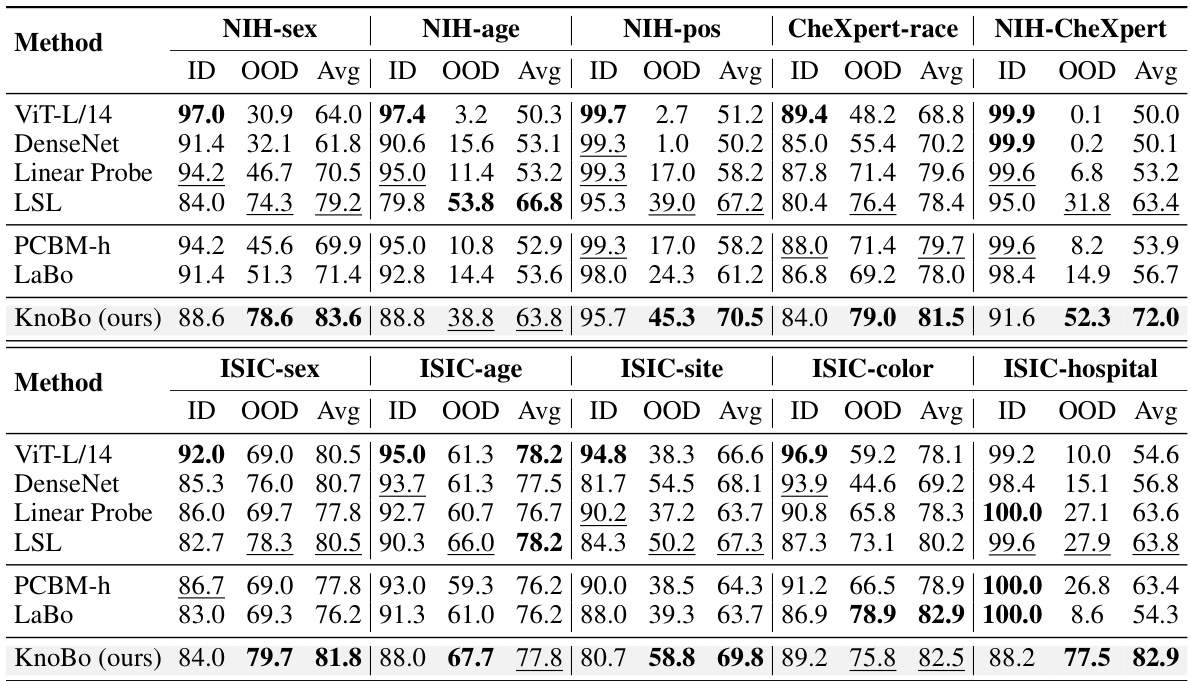

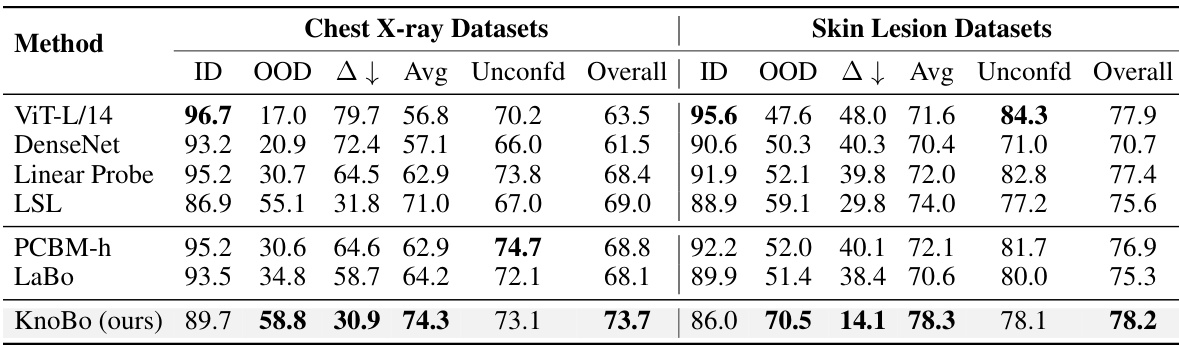

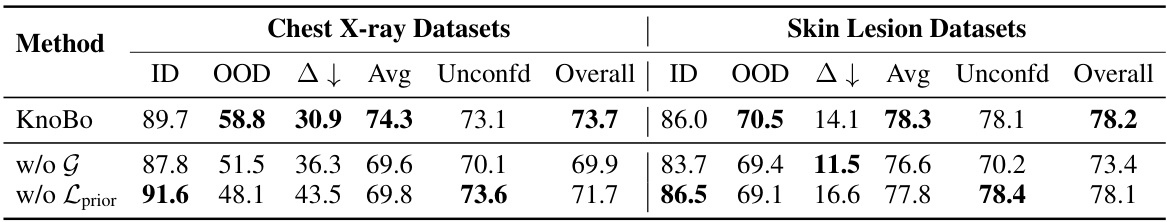

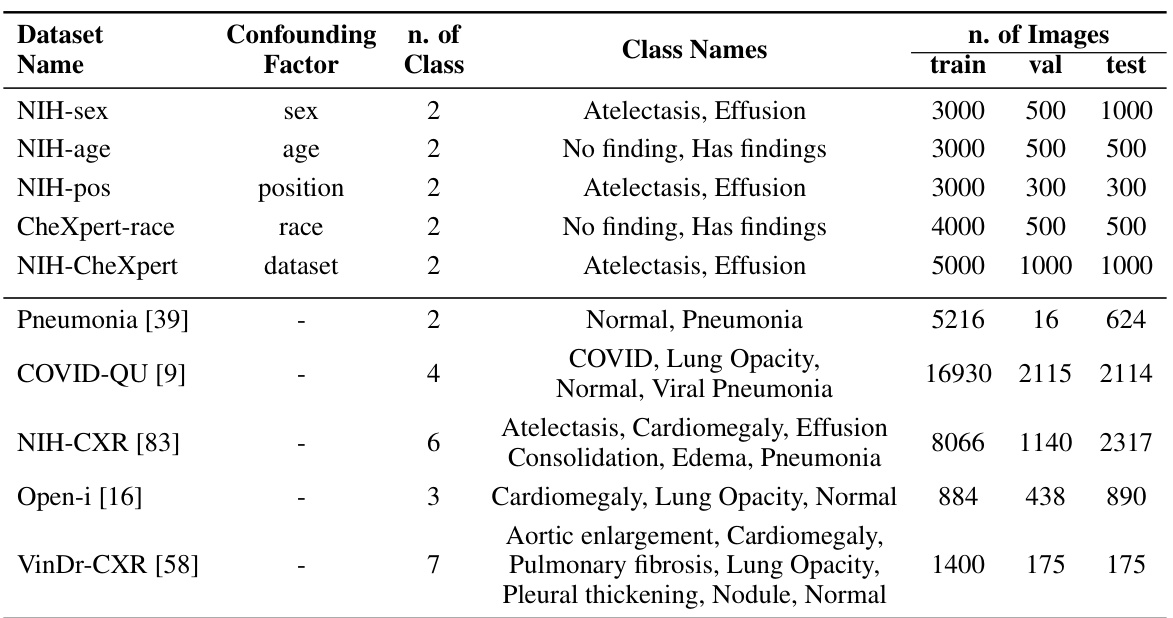

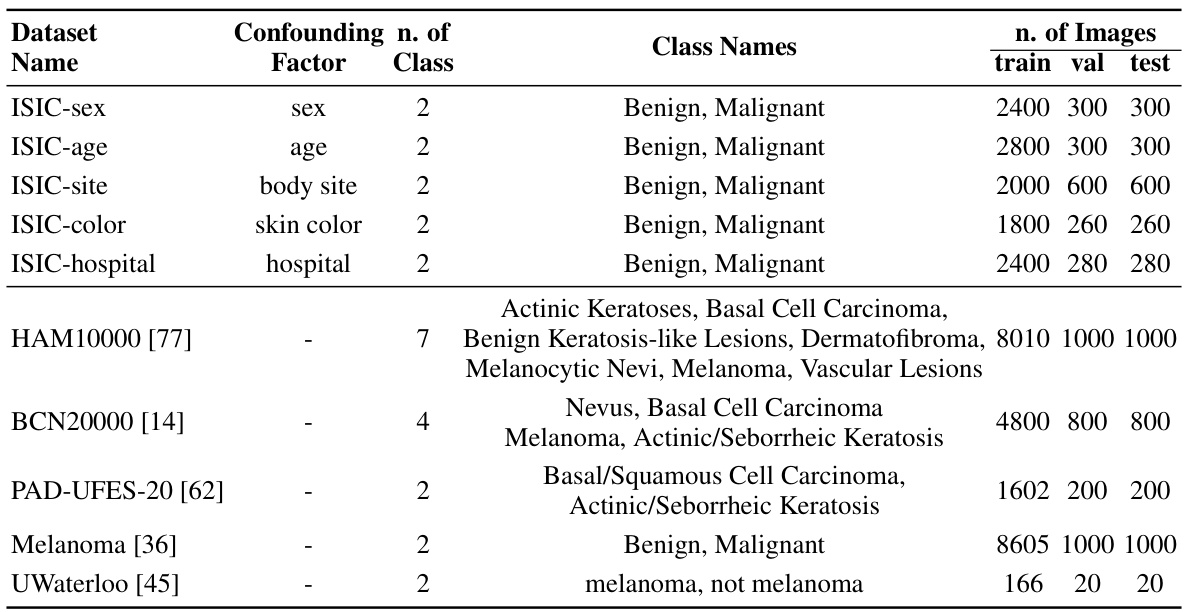

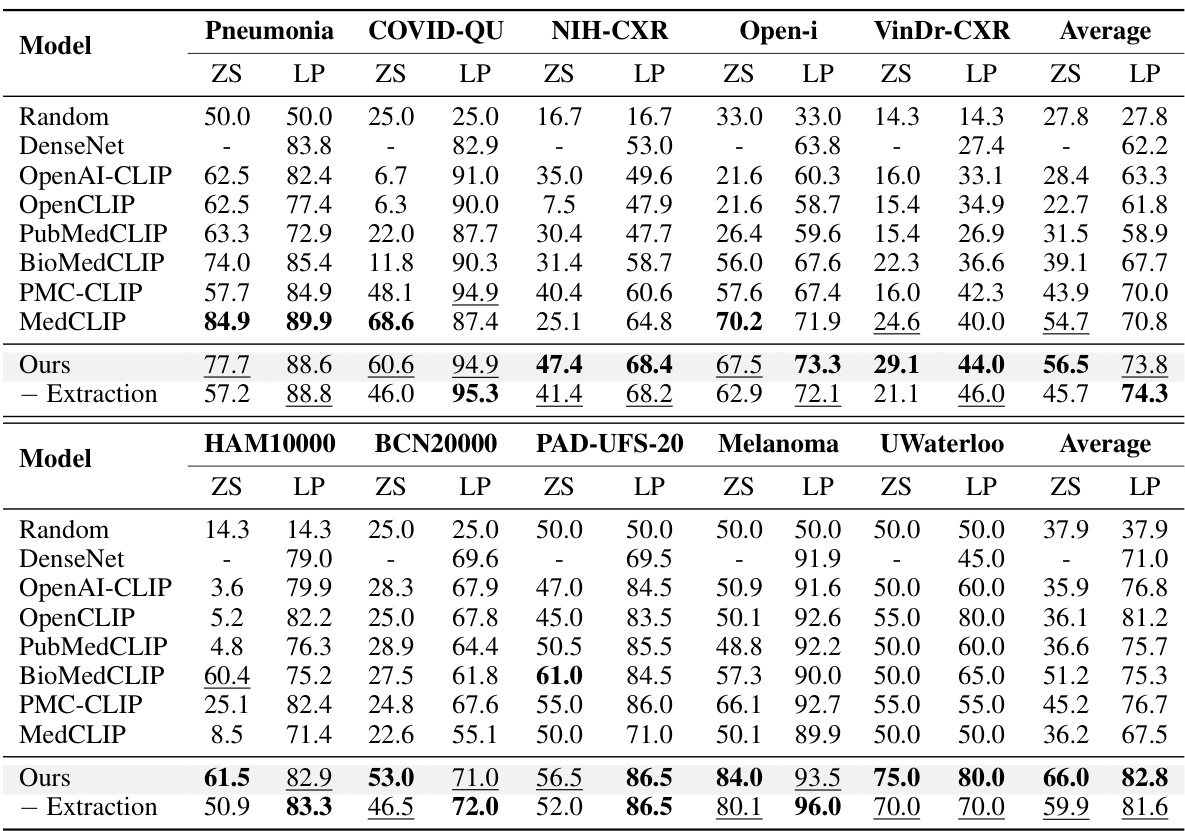

This table presents the performance comparison of different methods on 10 confounded datasets (5 chest X-ray and 5 skin lesion datasets). Each dataset is designed to evaluate model robustness to spurious correlations. The performance is evaluated using in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), and average accuracy. The best and second-best results for each metric are highlighted.

In-depth insights#

Medical Domain Priors#

The concept of “Medical Domain Priors” in the context of medical image analysis is crucial. It highlights the inadequacy of general-purpose visual backbones when directly applied to medical imaging tasks, due to the lack of inherent understanding of medical concepts and patterns. This necessitates the introduction of explicit medical knowledge as priors, effectively bridging the gap between raw image data and clinical interpretation. Methods such as incorporating information from medical textbooks or PubMed enable models to reason with clinically relevant features, significantly improving robustness against domain shifts. Knowledge-enhanced bottlenecks are a promising approach, leveraging readily available medical literature to create interpretable concept spaces that guide model learning and improve generalization. While this offers advantages, further investigation is needed to address challenges like data scarcity, confounder bias, and potential interpretability limitations inherent in using vast, heterogeneous medical knowledge bases. The development of stronger priors through more sophisticated techniques and better curated data is key for the future of accurate and trustworthy medical image analysis.

KnoBo Architecture#

The KnoBo architecture, designed for robust medical image analysis, cleverly integrates interpretability and generalizability. It leverages concept bottleneck models (CBMs), enhancing them with knowledge priors derived from medical literature (e.g., textbooks, PubMed). This prior knowledge, incorporated through a retrieval-augmented language model, guides the construction of an appropriate concept space, ensuring the model focuses on clinically relevant features. The architecture factors learning into three parts: a bottleneck predictor, a structure prior, and a parameter prior. The structure prior constrains the concept space using the knowledge base, making the model’s reasoning more transparent. The parameter prior, based on the knowledge priors, further refines model parameters for improved prediction. This three-pronged design effectively bridges explicit medical knowledge with image data, addressing the challenge of domain shifts in medical image classification and producing more robust and trustworthy results.

Knowledge Sources#

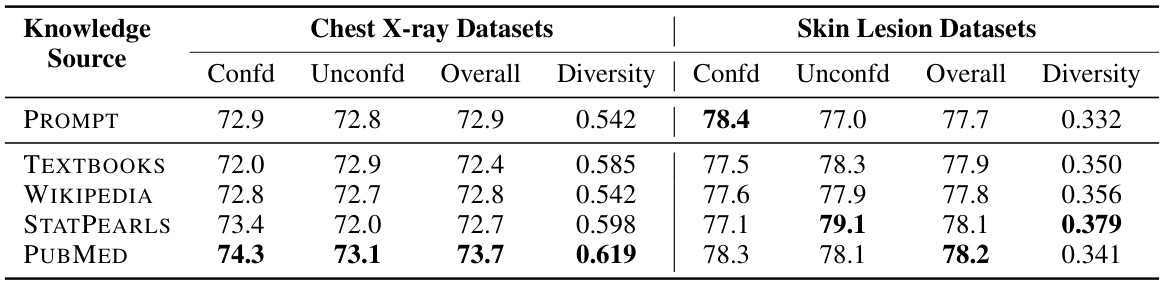

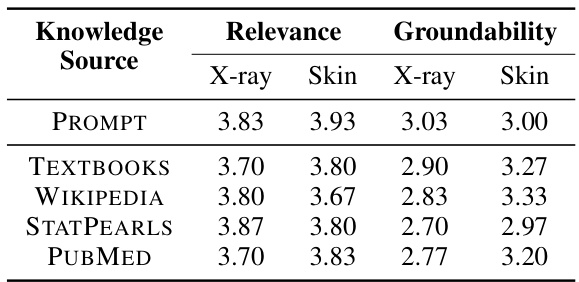

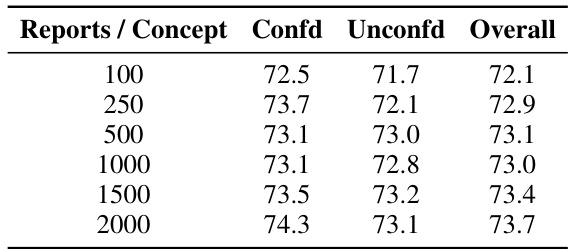

The choice of knowledge source significantly impacts the performance of knowledge-enhanced bottlenecks in medical image analysis. The study explores five different sources: PubMed, textbooks, Wikipedia, StatPearls, and prompts. PubMed consistently outperforms other sources, demonstrating the value of incorporating diverse and high-quality medical information. The diversity of concepts within each knowledge source also plays a crucial role, with PubMed exhibiting a higher diversity than other sources. This highlights the importance of leveraging comprehensive and nuanced medical knowledge rather than relying on limited or less-structured sources. The findings suggest a strong correlation between the quality of the knowledge base and the resulting model robustness, emphasizing that the selection of knowledge sources is a key factor in developing reliable and generalizable AI models for healthcare.

Robustness Evaluation#

A robust robustness evaluation is crucial for assessing the generalizability and reliability of any machine learning model, especially in high-stakes applications like medical image analysis. It should involve a multifaceted approach, going beyond simple accuracy metrics. Thorough testing on diverse datasets with variations in imaging modalities, acquisition parameters, patient demographics, and clinical contexts is key. Synthetically induced domain shifts, mimicking real-world variations such as changes in hospitals or equipment, should be incorporated. Out-of-distribution (OOD) detection and robustness are critical, evaluating performance on unseen data distributions. Beyond quantitative measures, qualitative analysis using visual explanations or human feedback can provide valuable insights into model behavior and limitations. Finally, a comprehensive reporting of results, including both in-distribution and OOD performance, along with detailed descriptions of the datasets and evaluation methods, is essential for transparency and reproducibility.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work on enhancing robustness in medical image analysis using knowledge priors could involve several key areas. Expanding the scope of medical modalities beyond chest X-rays and skin lesions is crucial, encompassing diverse imaging techniques like CT, MRI, and ultrasound. Investigating different knowledge sources and their impact on model performance warrants further exploration, examining the influence of various medical textbooks, databases, and clinical guidelines. Improving the efficiency of concept grounding, perhaps through more advanced large language models, could significantly accelerate the process and reduce computational burden. A thorough evaluation of KnoBo’s performance on larger and more diverse datasets is important to establish its generalizability and clinical utility. Finally, exploring methods for combining knowledge priors with other domain adaptation techniques promises to further improve robustness and accuracy in real-world medical image analysis scenarios. Developing methods for integrating this type of knowledge into already-existing deep learning models rather than designing separate models also would be a valuable research area.

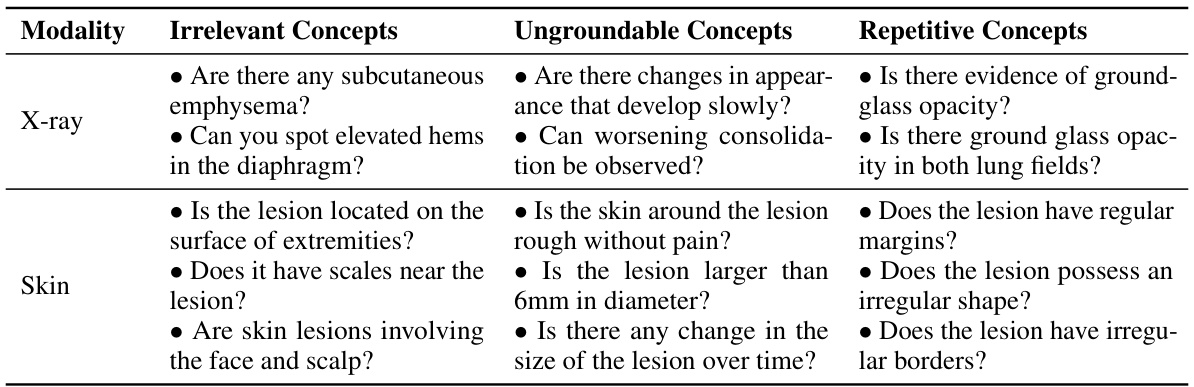

More visual insights#

More on figures

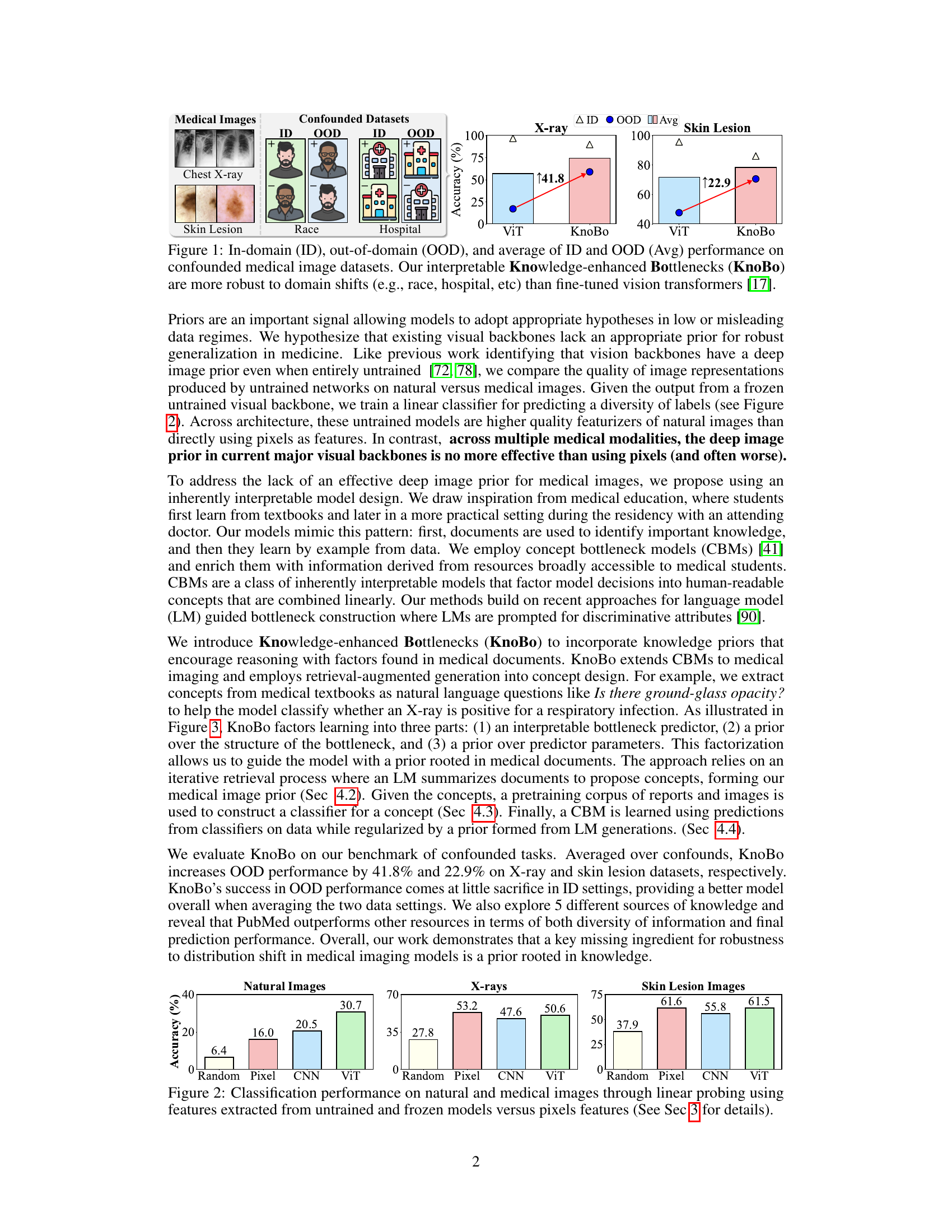

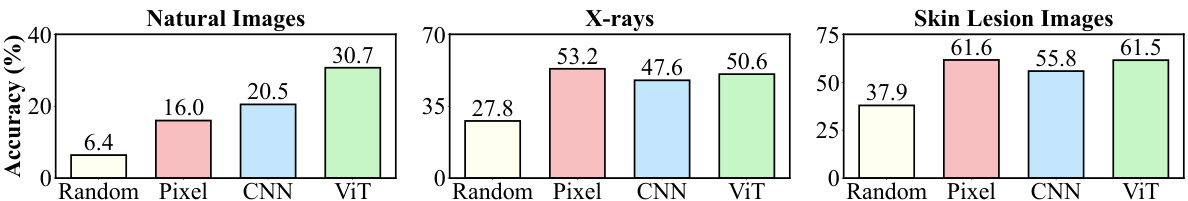

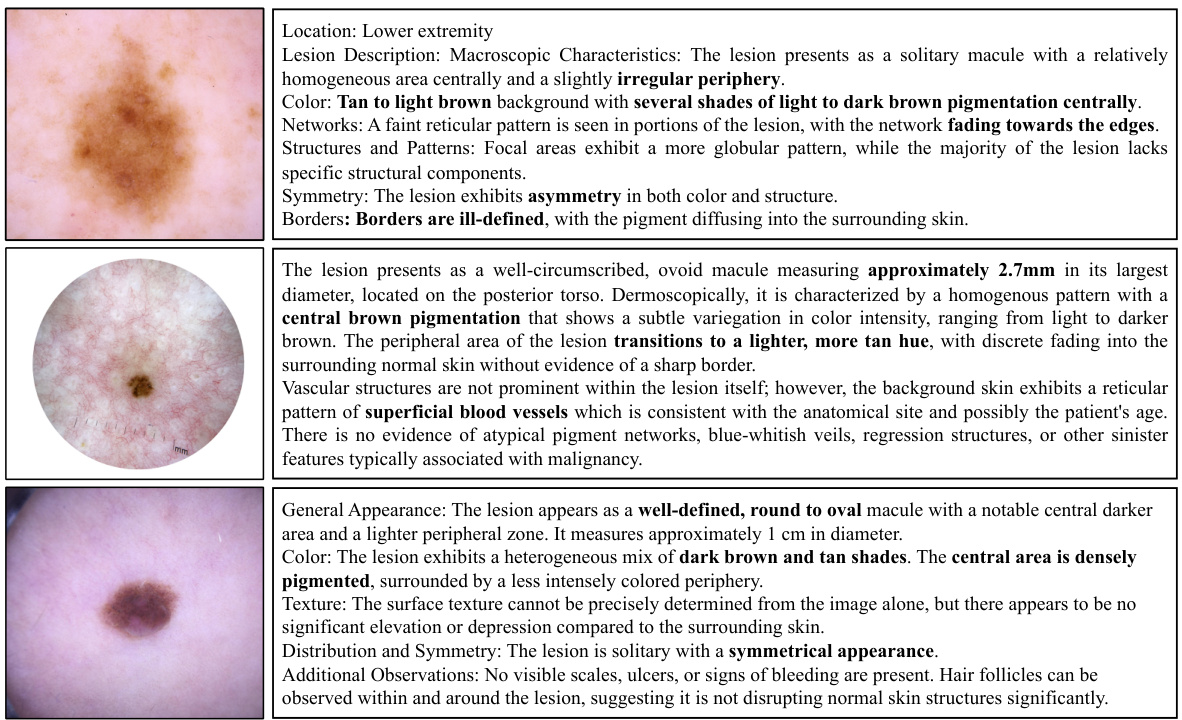

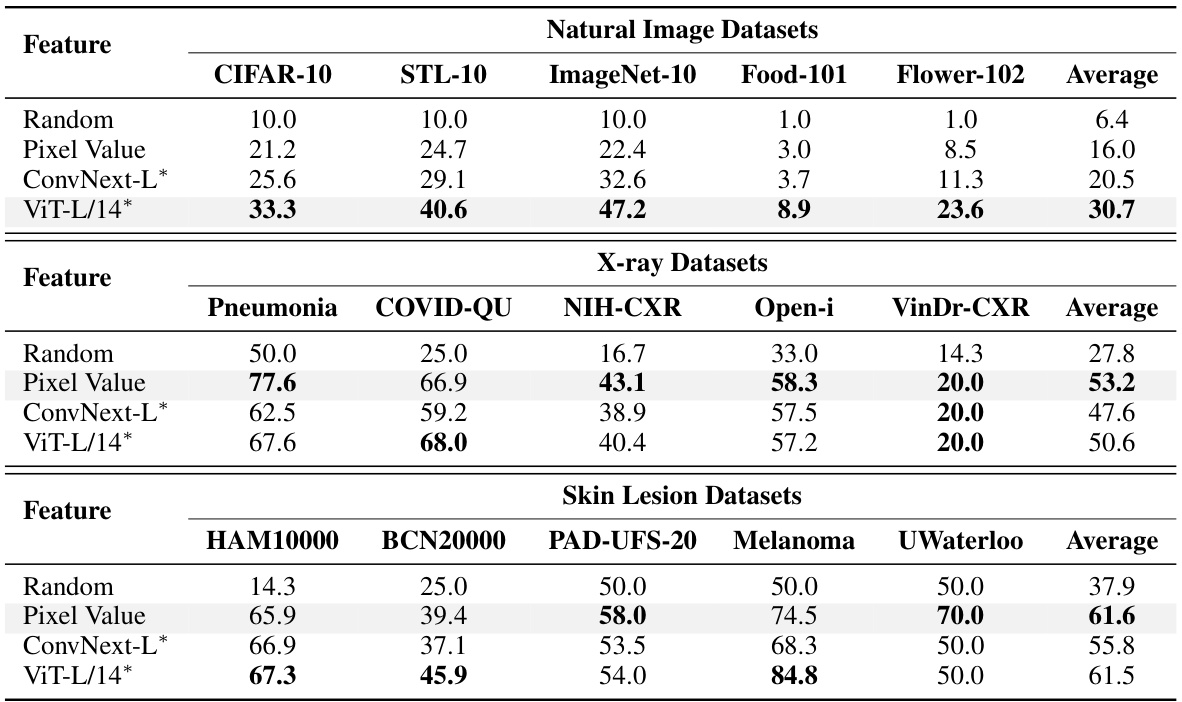

This figure compares the performance of using different feature extraction methods (random pixel values, features from untrained CNN, ViT models) for image classification tasks across natural images and medical images (X-rays, skin lesions). Linear probing was used to evaluate the quality of image representations generated by each method, by training a linear classifier on top of the features. The results indicate that while existing visual backbones are effective at extracting features from natural images, they are not as effective for medical images, where raw pixel values sometimes perform better.

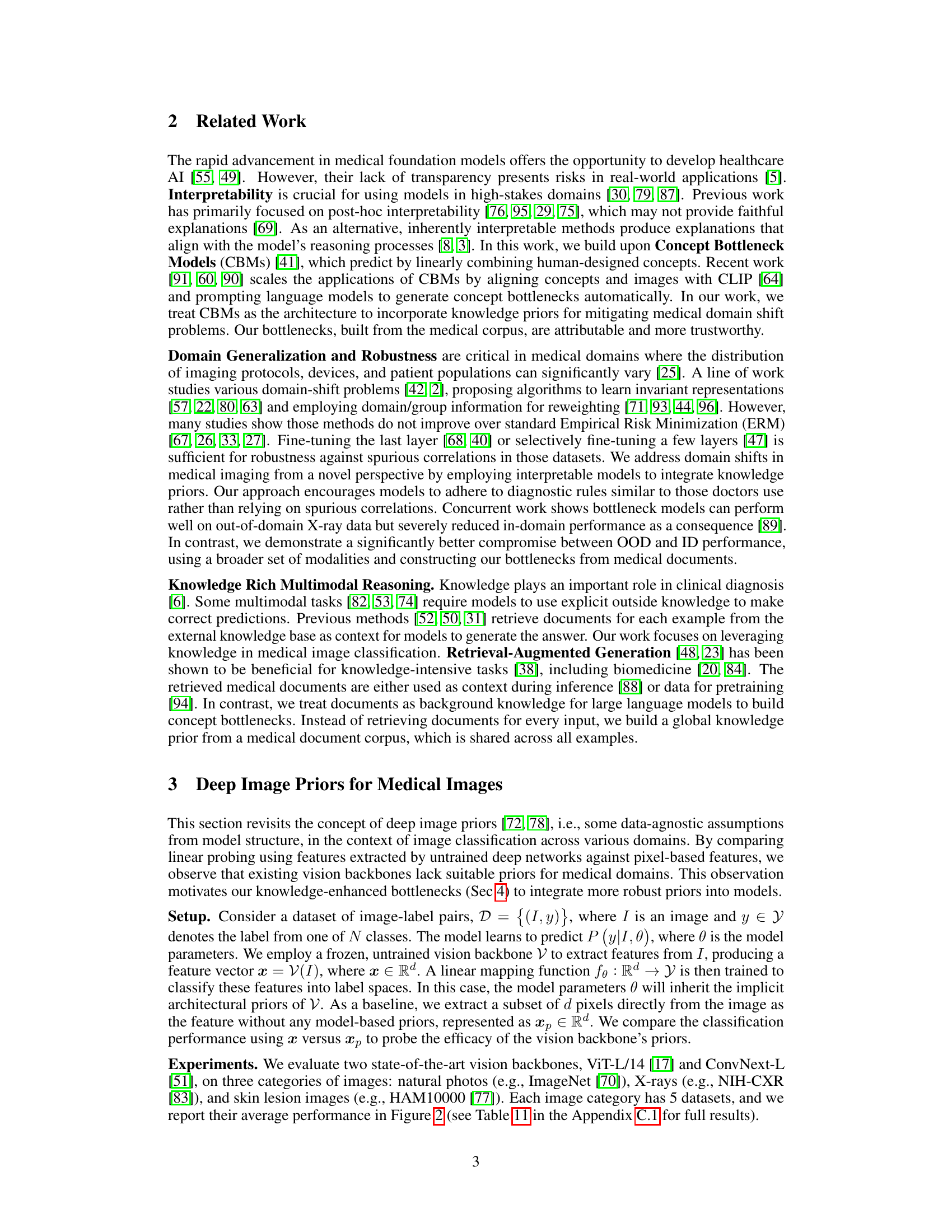

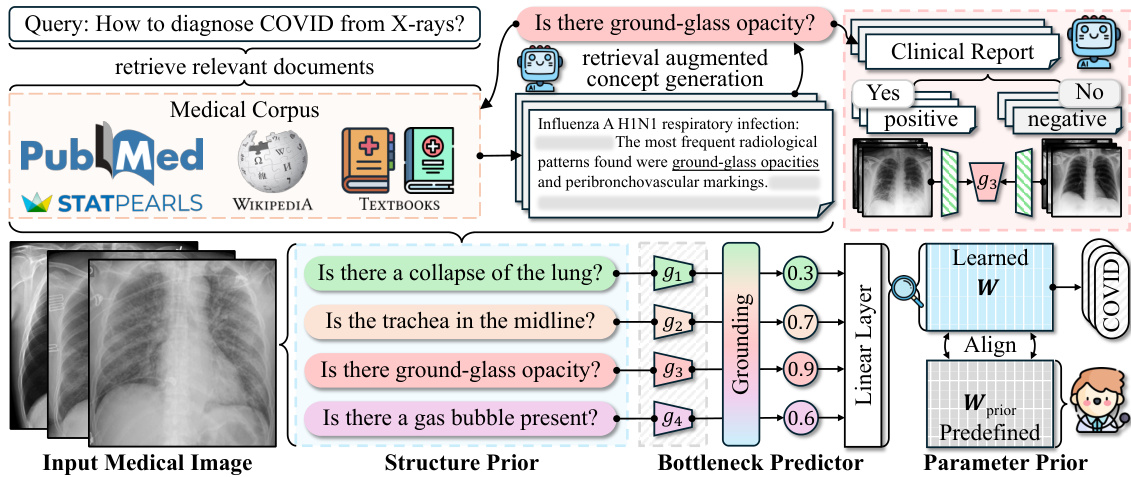

This figure illustrates the architecture of the Knowledge-enhanced Bottlenecks (KnoBo) model. It shows three main components working together: 1. Structure Prior: Uses medical documents to create a concept bottleneck. This bottleneck helps the model focus on clinically relevant factors. 2. Bottleneck Predictor: Maps the input medical image to the concept space created in the Structure Prior stage. It produces a probability of each concept for the input image. 3. Parameter Prior: Constrains the model parameters with information from the medical literature or expert knowledge, making the model less sensitive to biases and spurious correlations in the training data. These components work together to produce a final classification result.

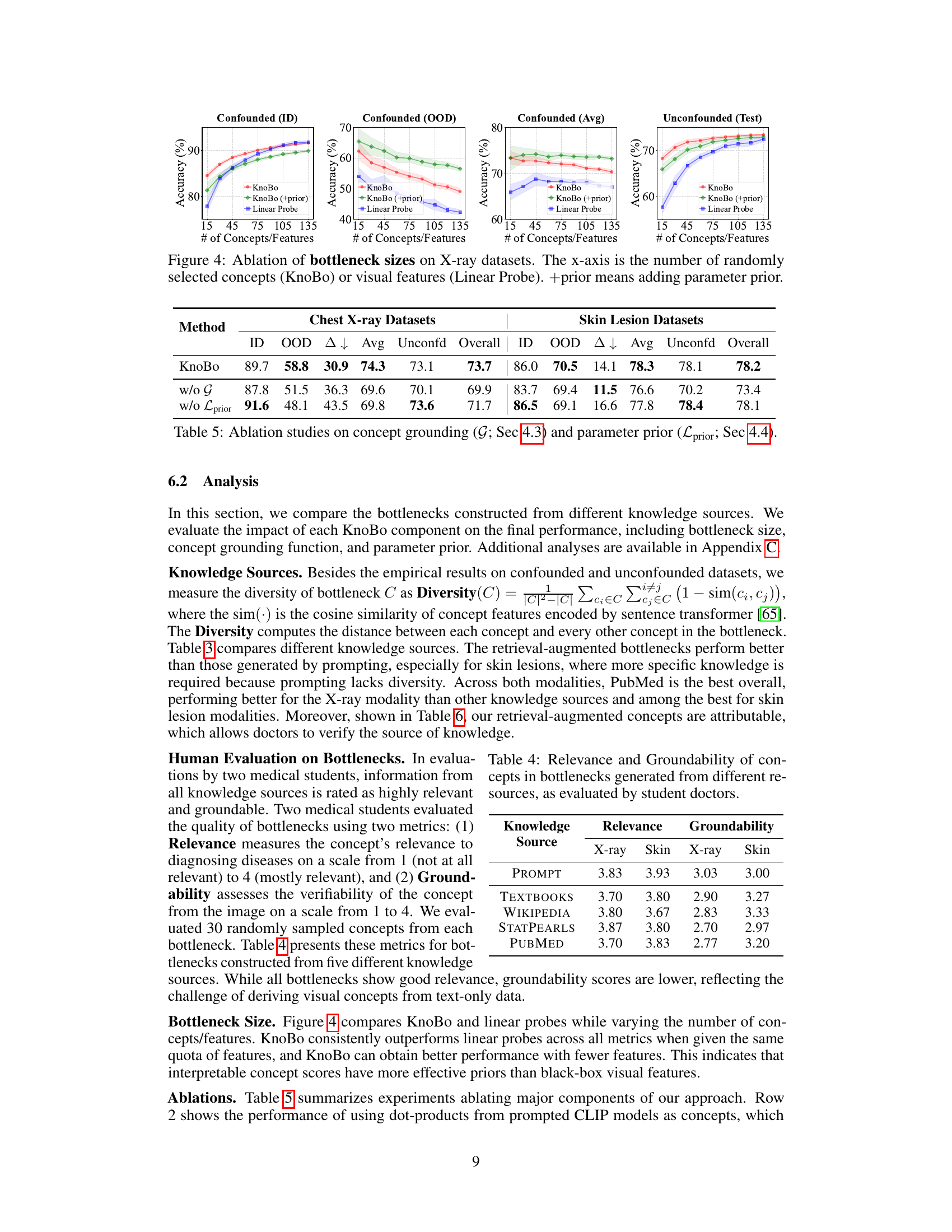

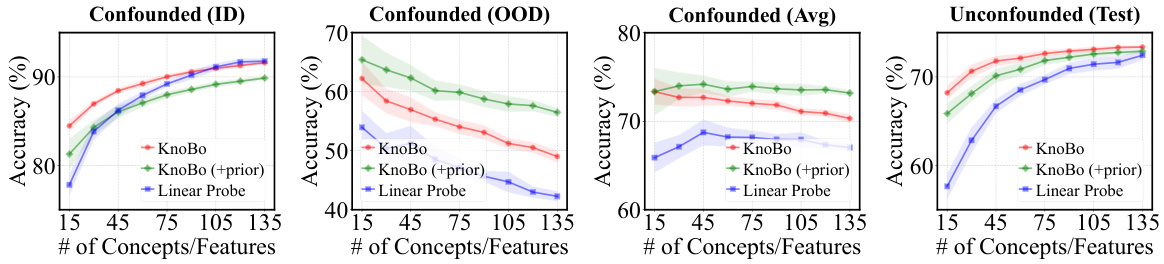

This ablation study analyzes the effect of varying the number of concepts or features used in the model on its performance across different evaluation metrics (in-domain, out-of-domain, average, and unconfounded). It compares KnoBo (with and without a parameter prior) against a linear probe baseline. The results show how the choice of bottleneck size impacts the model’s robustness and accuracy.

This figure illustrates the architecture of Knowledge-enhanced Bottlenecks (KnoBo), a novel method for medical image classification. KnoBo uses three main components to improve model performance and robustness to domain shifts. The Structure Prior utilizes medical documents to construct a reliable bottleneck. The Bottleneck Predictor maps input images onto concepts defined by the prior, which are then used by a linear layer to predict the final label. Finally, the Parameter Prior leverages prior knowledge from medical experts to guide the training process of the linear layer.

This figure shows the results of an ablation study on the number of concepts or features used in the model for chest X-ray image classification. The x-axis represents the number of concepts (for KnoBo) or features (for the Linear Probe baseline). The y-axis shows the accuracy achieved on different types of datasets: in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), the average of both (Avg), and unconfounded test data. Separate lines and shaded areas represent the performance of KnoBo and the linear probe baseline, with and without the addition of a parameter prior.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed KnoBo model and a baseline model (fine-tuned vision transformers) on medical image datasets. The datasets are designed to have confounding factors such as race or hospital. The results show that KnoBo is more robust to these domain shifts, achieving better in-domain and out-of-domain performance than the baseline model. The figure shows the accuracy of each model on in-domain data, out-of-domain data and an average of both.

This figure compares the performance of the proposed KnoBo model and a standard vision transformer (ViT) model on medical image datasets that have been artificially confounded with various factors (race, hospital, etc.). The ID (in-distribution) performance represents accuracy when the model is trained and tested on data from the same distribution. The OOD (out-of-distribution) performance shows how well the model generalizes to data with a different distribution due to the confounding factors. The Avg represents the average of ID and OOD, showing an overall robustness metric. The figure demonstrates KnoBo’s improved robustness against domain shifts.

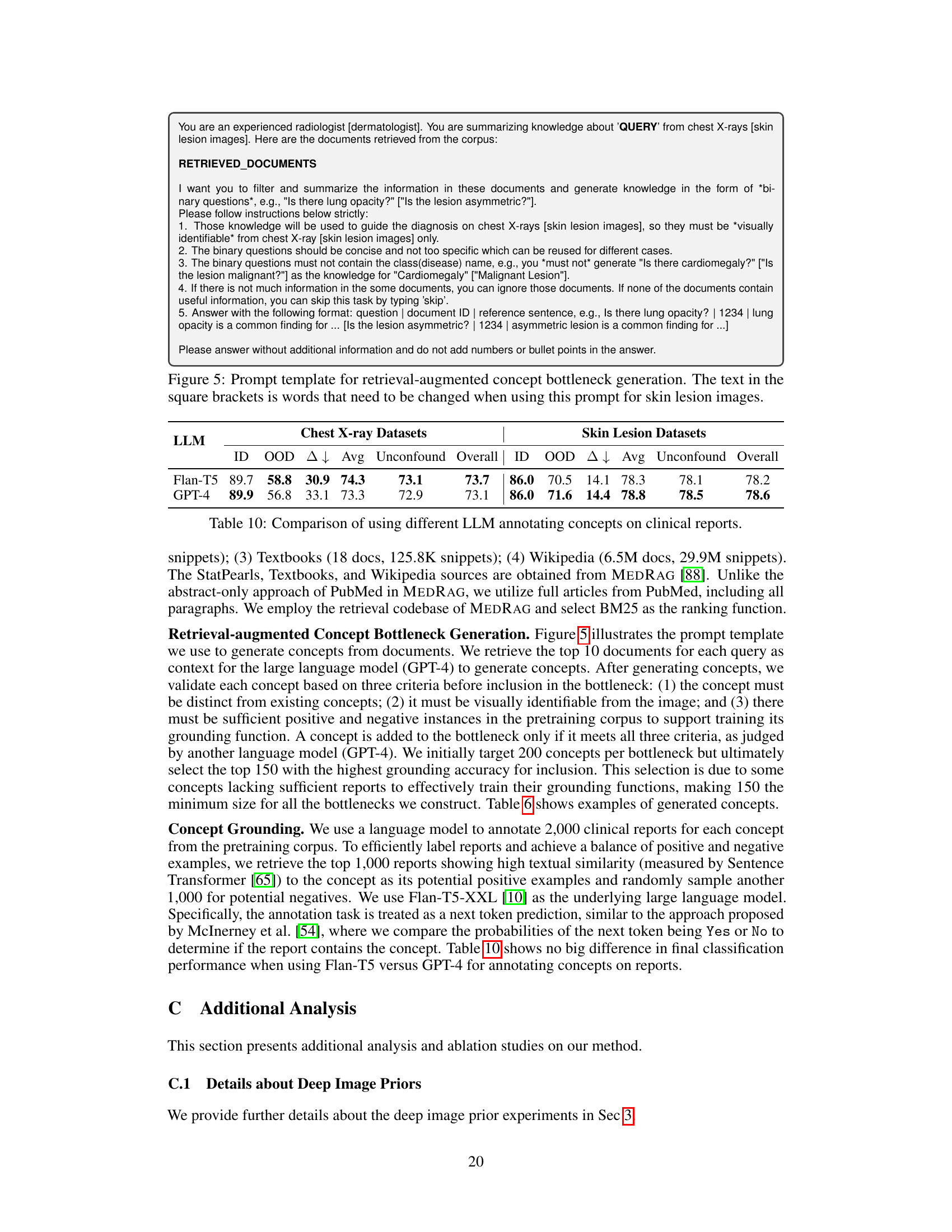

More on tables

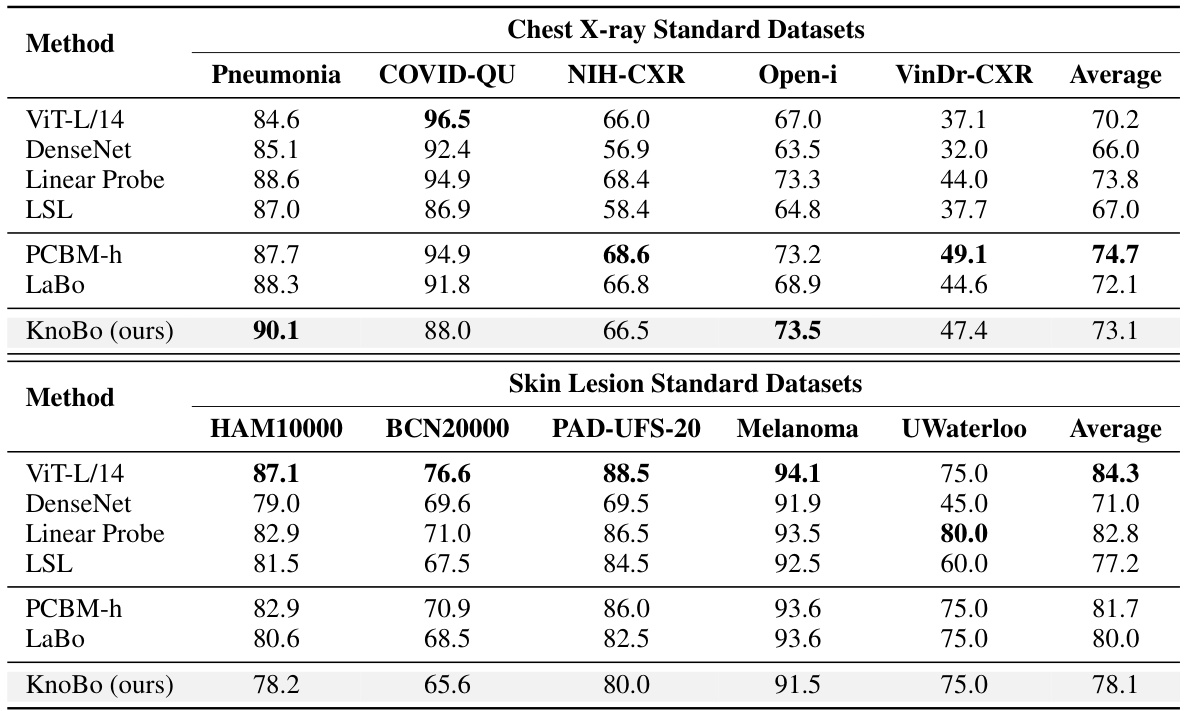

This table presents the performance of different methods on 10 confounded datasets (5 chest X-ray and 5 skin lesion datasets). Each dataset introduces a specific confound (e.g., sex, age, hospital). The table shows the in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), and average accuracy for each method on each dataset. The best and second-best results for each column are highlighted.

This table presents the performance of various methods on 10 confounded datasets for two medical image modalities: chest X-rays and skin lesions. For each dataset, it shows the in-domain (ID) accuracy, the out-of-domain (OOD) accuracy, the average of ID and OOD accuracies (Avg), and the best performing method for each metric. The datasets are designed to test model robustness to various confounding factors such as sex, age, race, etc. The results highlight the impact of domain shifts on model performance and demonstrates the relative robustness of certain methods compared to others.

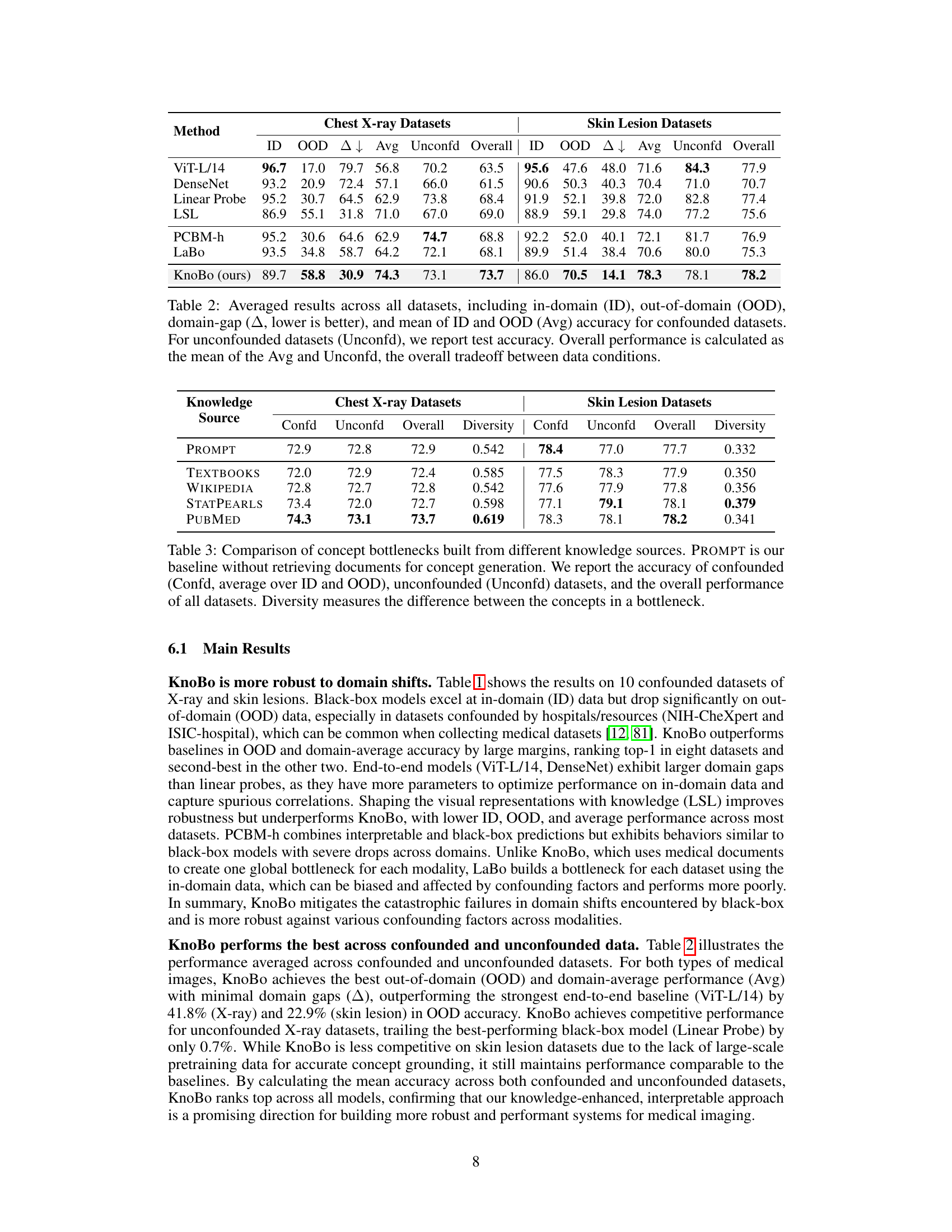

This table compares the performance of concept bottlenecks built using different knowledge sources (PROMPT, TEXTBOOKS, WIKIPEDIA, STATPEARLS, PUBMED). For each source, it shows the accuracy on confounded (average of in-domain and out-of-domain) and unconfounded datasets, as well as an overall accuracy which averages both. A diversity metric is also provided, which measures the difference between concepts within each bottleneck.

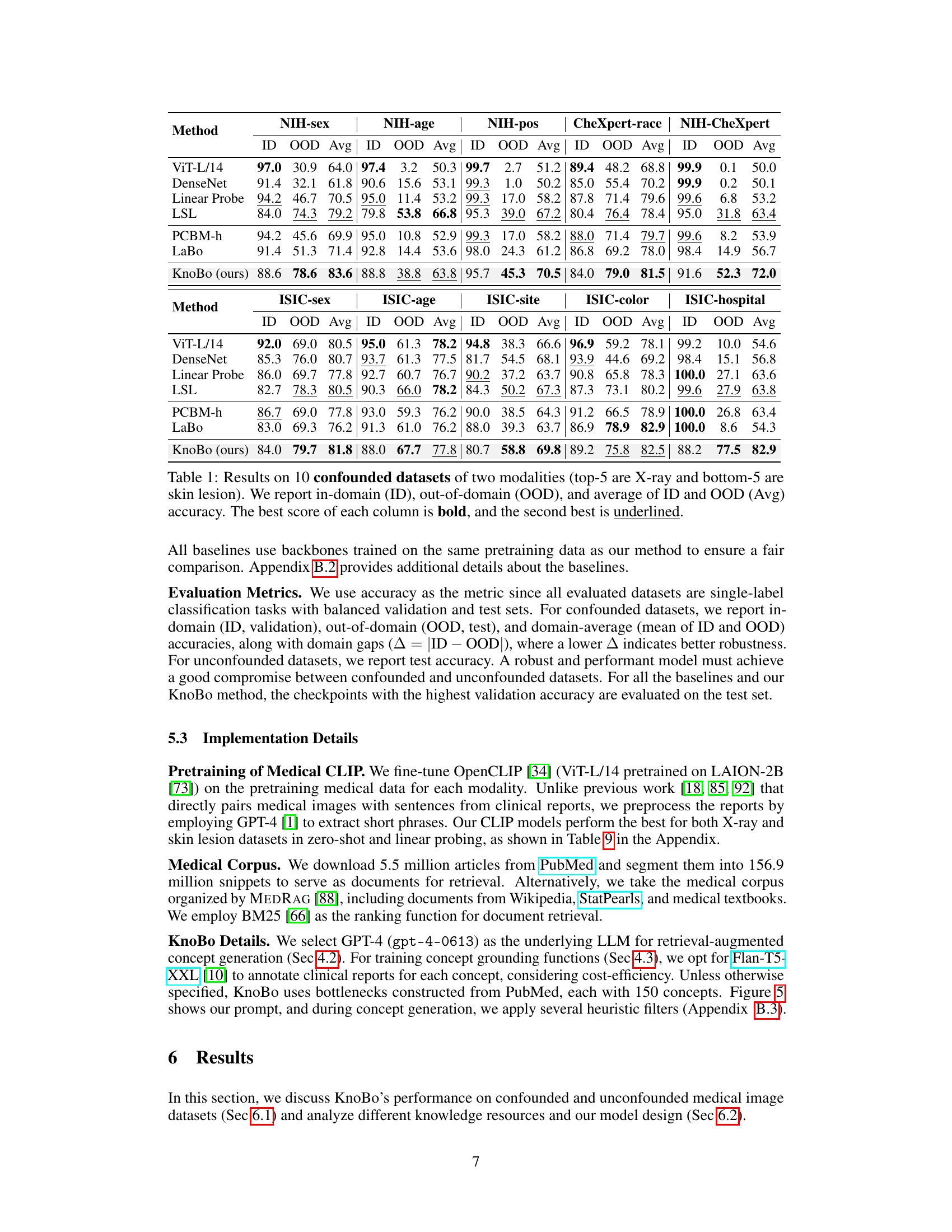

This table summarizes the performance of various methods across all datasets, both confounded and unconfounded. It shows in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), and average accuracy for the confounded datasets and reports the test accuracy for the unconfounded datasets. The domain gap (∆) which represents the difference between ID and OOD accuracy indicates model robustness. Finally, it calculates an overall performance score that considers both types of datasets to assess the overall model effectiveness.

This table shows the performance of different methods on 10 confounded datasets (5 chest X-ray and 5 skin lesion datasets). Each dataset introduces a specific confounding factor, creating a spurious correlation between the label and the confounding factor. The table reports the in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), and average accuracy for each method and dataset. The best performing method for each column is highlighted in bold, and the second-best is underlined. This demonstrates the robustness of each method to domain shifts caused by the different confounding factors.

This table presents the performance of different models on 10 confounded datasets (5 chest X-ray and 5 skin lesion datasets). Each dataset has a specific confounding factor, and the model performance is evaluated using in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), and average accuracy metrics. The best performing model for each metric in each dataset is highlighted in bold.

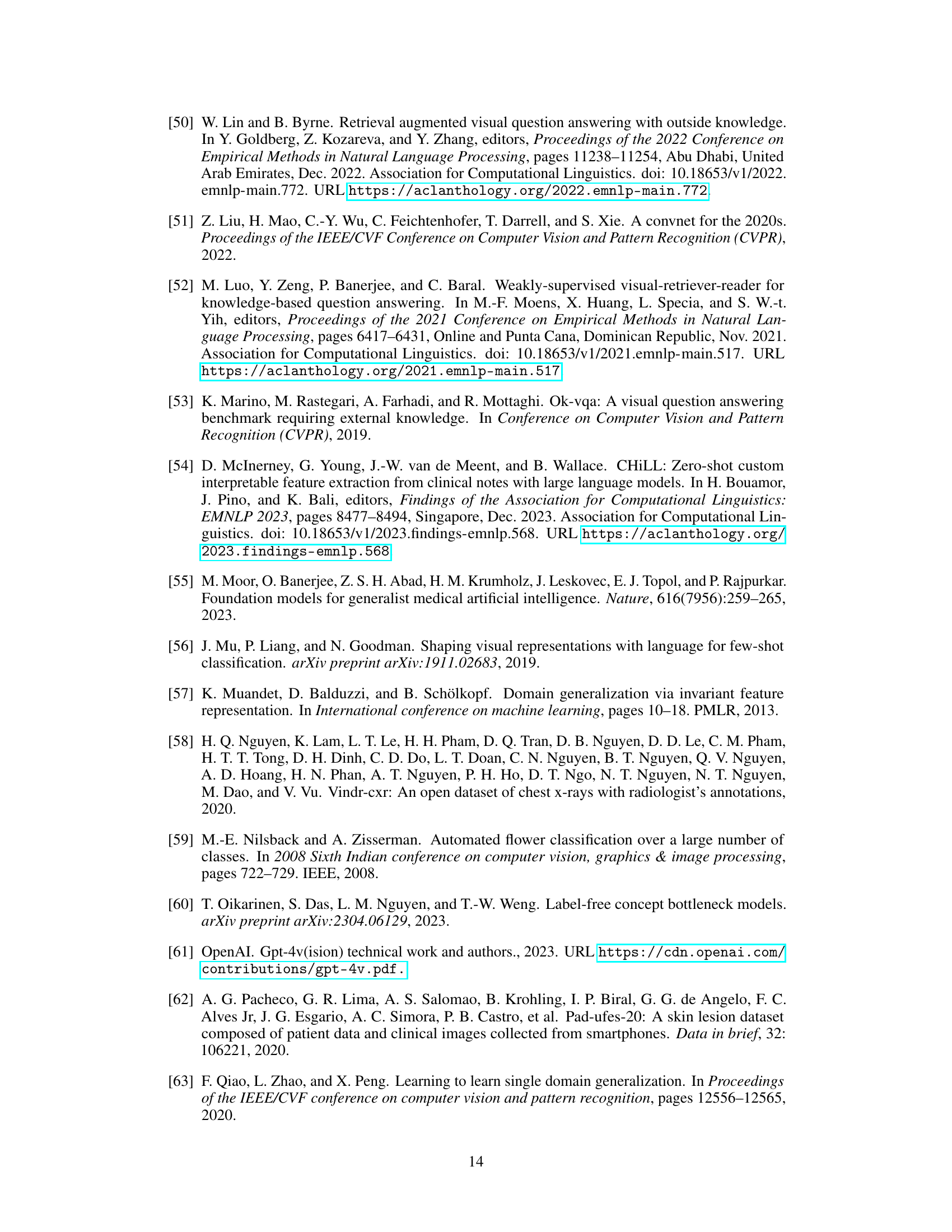

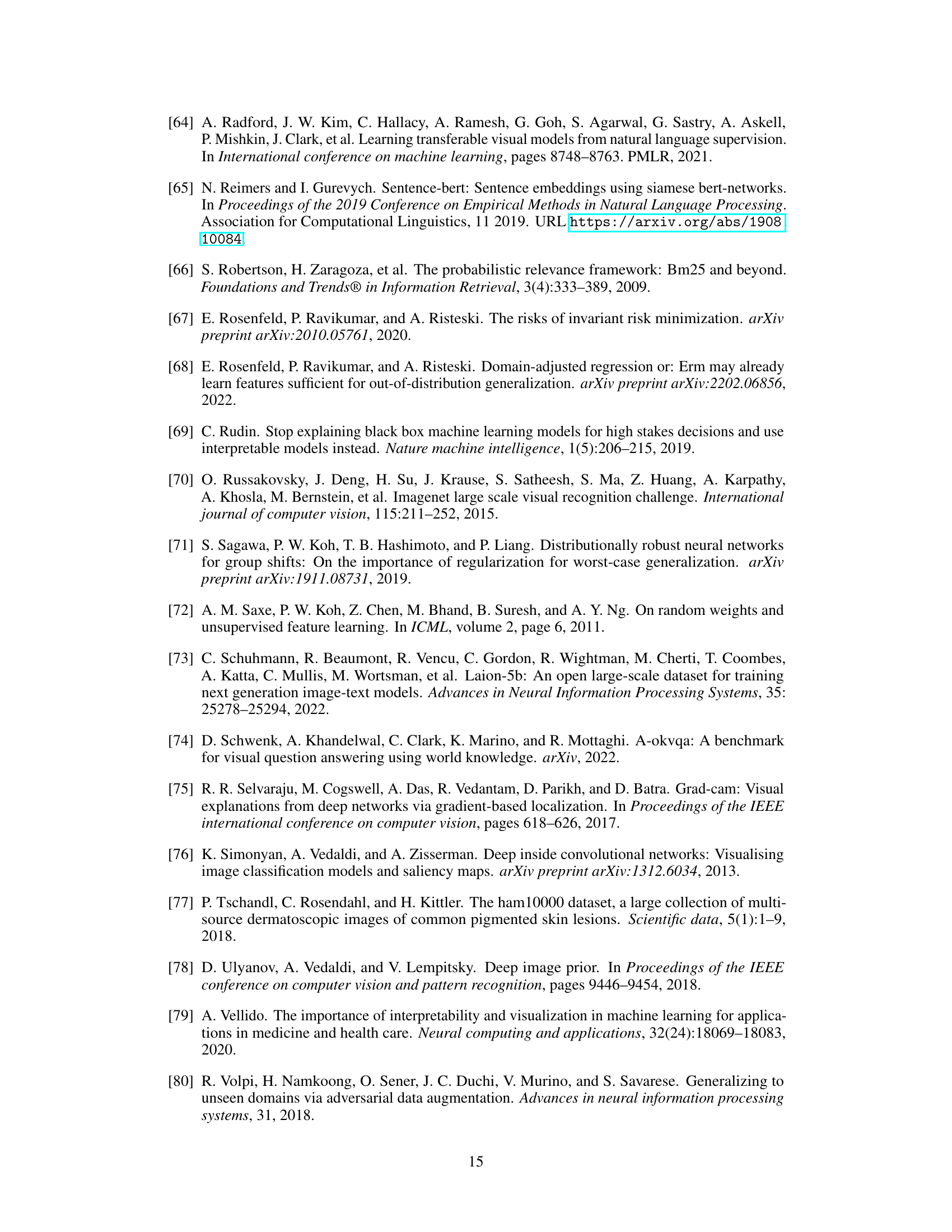

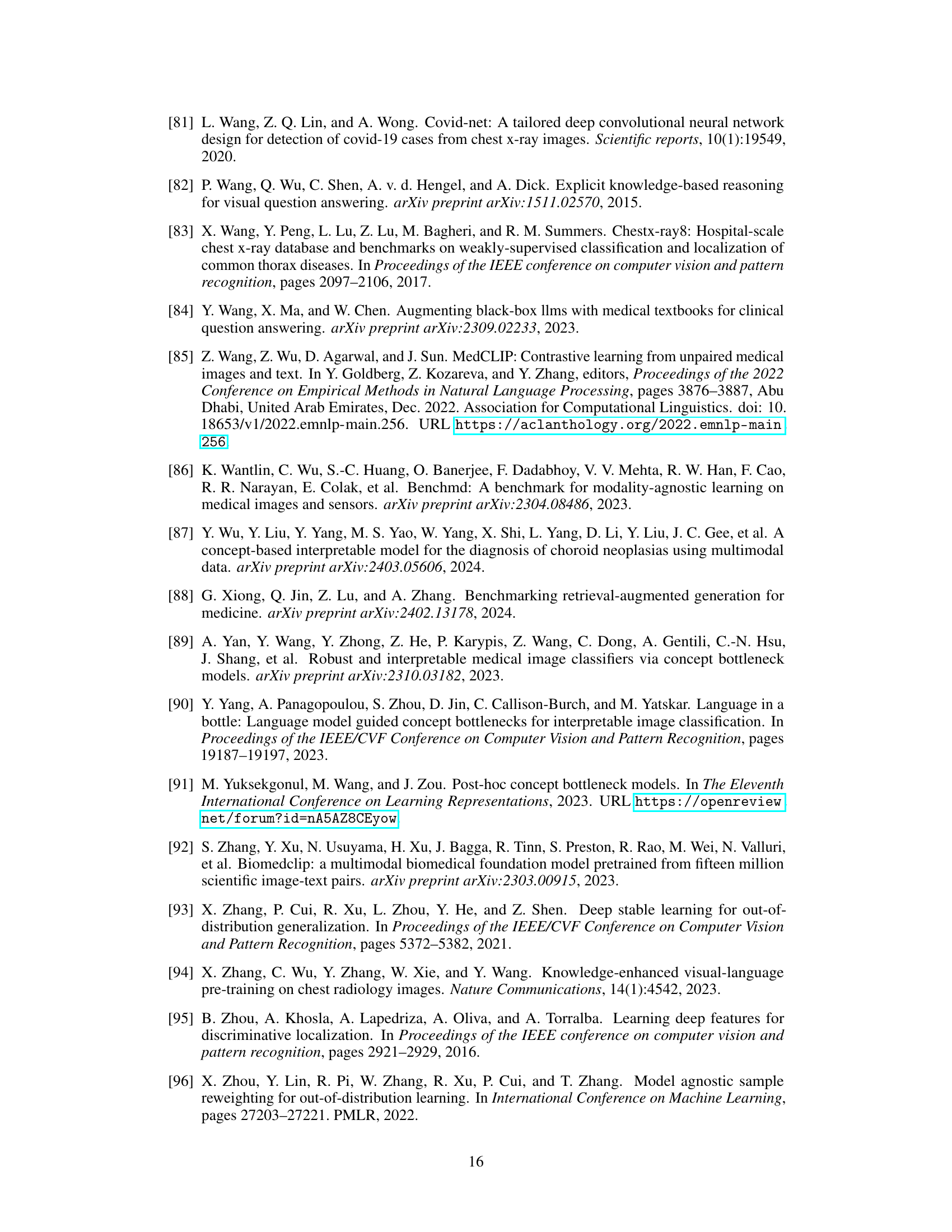

This table presents detailed information on the ten chest X-ray datasets used in the study. For each dataset, it lists the confounding factor used to create spurious correlations (if any), the number of classes in the dataset, the names of those classes, and the number of images used for training, validation, and testing. This allows a reader to understand the characteristics of the data used in the experiments and how the data was split for training, validation, and testing.

This table presents the performance of different models on 10 confounded datasets for chest X-rays and skin lesions. It shows in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD) accuracy, and the average of both (Avg). The best and second-best results for each dataset and metric are highlighted. The results demonstrate the impact of confounding factors on model performance.

This table shows the performance of various models on 10 confounded datasets (5 chest X-ray and 5 skin lesion datasets). Each dataset has a specific confounding factor (e.g., sex, age, race, hospital) that is reversed between the training and testing sets to assess the models’ robustness to domain shifts. The table reports the in-domain accuracy (ID), out-of-domain accuracy (OOD), and the average of the two. The best and second-best results for each metric are highlighted.

This table presents the performance of various methods on 10 confounded datasets for chest X-ray and skin lesion image classification. The results show in-domain accuracy (ID), out-of-domain accuracy (OOD), the average of these two (Avg), and the difference between them (Δ). The best and second-best performances are highlighted in each column.

This table presents the performance of different models on 10 confounded datasets, 5 for chest X-ray and 5 for skin lesions. The datasets are designed to evaluate the robustness of models to domain shifts by introducing spurious correlations between the class labels and various confounding factors (sex, age, position, race, and dataset). The table shows the in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), and average accuracy for each model and dataset. The best performing model for each metric is highlighted in bold, with the second-best underlined.

This table presents the performance of different methods on 10 confounded datasets for two medical image modalities (chest X-ray and skin lesion). The datasets are designed to evaluate model robustness to domain shifts by introducing spurious correlations. For each dataset and method, the in-domain (ID) accuracy, out-of-domain (OOD) accuracy, and their average are reported. The best and second-best performing methods for each metric are highlighted.

This table compares the performance of concept bottlenecks generated using different knowledge sources (PROMPT, TEXTBOOKS, WIKIPEDIA, STATPEARLS, and PUBMED) on both confounded and unconfounded medical image datasets. It shows the accuracy (ID, OOD, Avg) for each source and also calculates the diversity of the concepts within each bottleneck, indicating the variety of information captured by each source. PubMed consistently achieves higher accuracy and demonstrates a higher diversity of concepts compared to the other sources.

This table shows the performance of different models on 10 confounded datasets (5 chest X-ray and 5 skin lesion datasets). Each dataset has a different confounding factor (e.g., sex, age, race, hospital). The table displays the in-domain (ID) accuracy, the out-of-domain (OOD) accuracy, and the average of these two. The best performing model for each metric is highlighted in bold, and the second-best is underlined. This allows for comparison of model robustness to domain shifts.

This table presents the performance of various models on 10 confounded datasets (5 chest X-ray and 5 skin lesion datasets). Each dataset introduces a specific confound (e.g., sex, age, race, hospital). The table shows the in-domain (ID), out-of-domain (OOD), and average accuracy for each model and dataset. The best and second-best performing models for each metric are highlighted in bold and underlined respectively. This allows for a comparison of model robustness across different confounds and modalities.

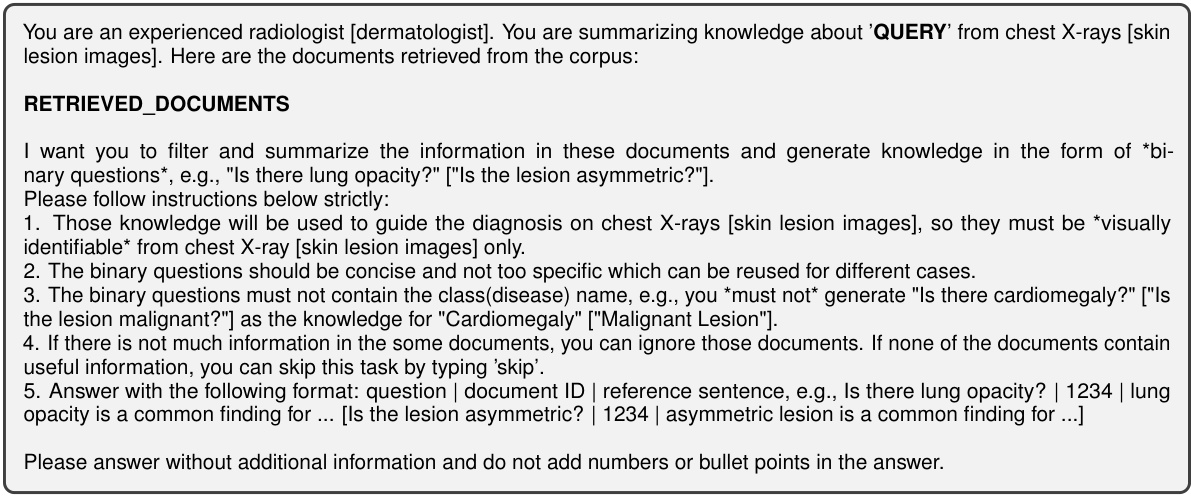

Full paper#