↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional Bayesian Optimization (BO) methods struggle with computationally expensive black-box optimization problems due to slow convergence. Recent research explores transfer learning to speed up the optimization process, focusing on transferring search spaces, but existing methods are not adaptive or flexible enough to identify promising subspaces efficiently. This paper introduces MCTS-transfer, a novel search space transfer method that iteratively divides, selects, and optimizes a learned subspace using Monte Carlo tree search.

MCTS-transfer offers several advantages. First, it provides a well-performing search space for warm-start optimization. Second, it adaptively identifies and leverages information from similar source tasks to improve the subspace search. This adaptive approach is crucial because it allows for the efficient identification of promising areas within the search space during the optimization process. Third, it demonstrates superior performance compared to other search space transfer methods on different optimization tasks. The results highlight its potential to significantly advance black-box optimization in various real-world applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it proposes a novel search space transfer learning method that significantly improves the efficiency and effectiveness of black-box optimization. This is crucial for many real-world applications, such as neural architecture search and hyperparameter optimization, where evaluating objective functions can be computationally expensive. The method’s ability to adaptively identify and leverage information from similar source tasks makes it particularly relevant to current research trends in transfer learning and Bayesian optimization. Furthermore, the use of Monte Carlo tree search offers a new avenue for exploration and exploitation in the search space, opening up opportunities for further research into more efficient and robust optimization strategies.

Visual Insights#

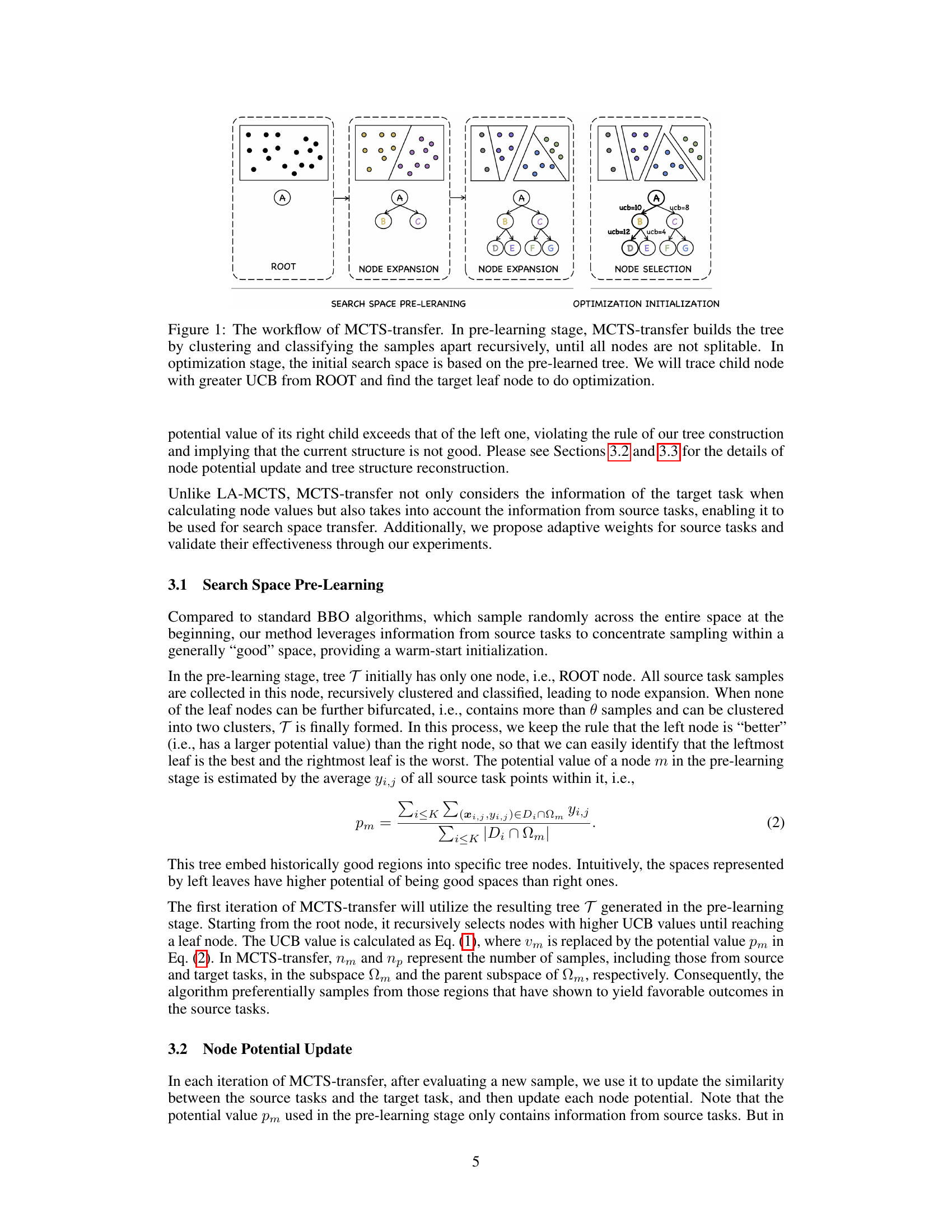

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of MCTS-transfer. The pre-learning stage uses a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to iteratively partition the search space based on data from source tasks. This creates a tree structure where each node represents a subspace. The optimization stage then uses this pre-learned tree to guide the optimization of the target task. Starting from the root node, the algorithm selects a leaf node with the highest Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) value and performs optimization within the corresponding subspace. New data from the target task is then used to update the tree structure and guide further optimization.

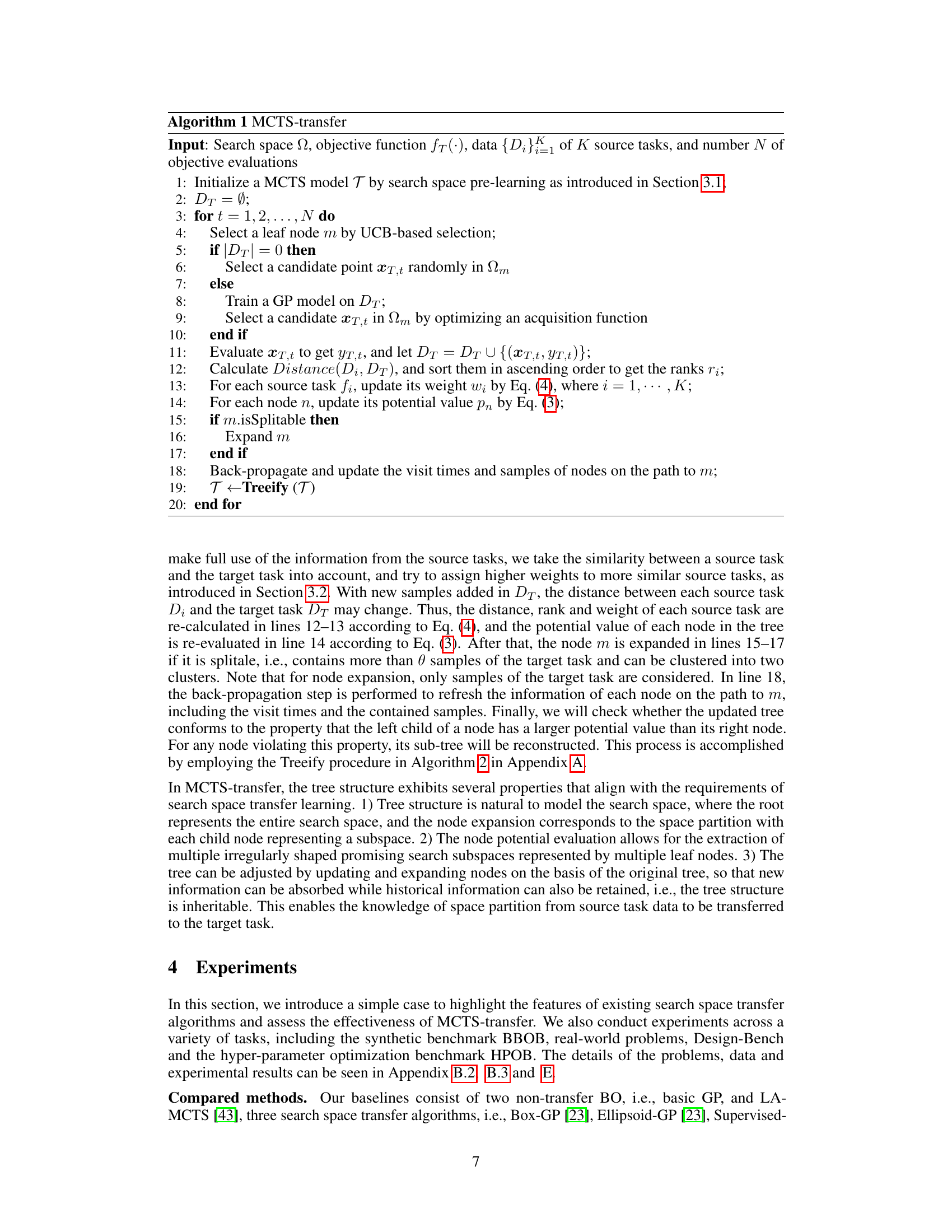

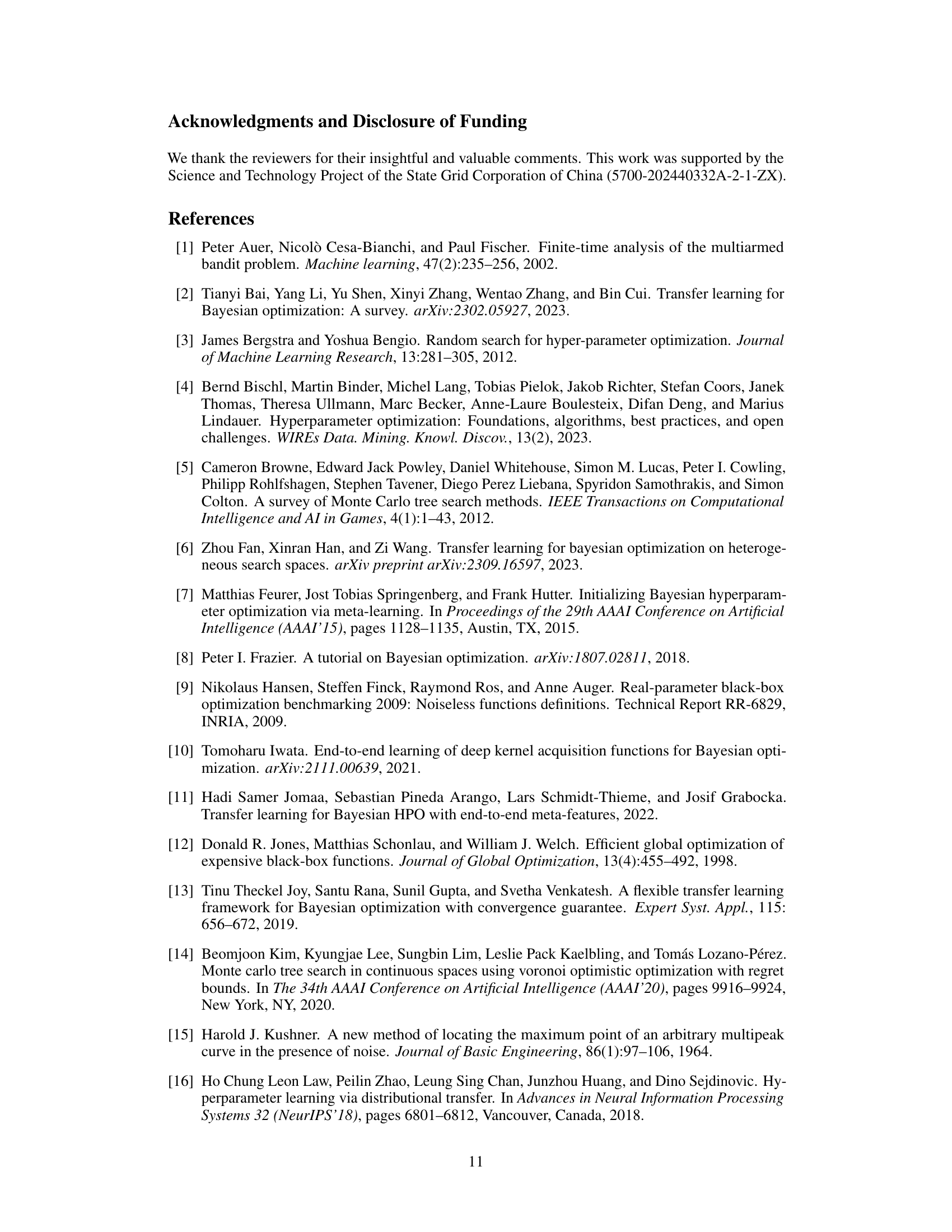

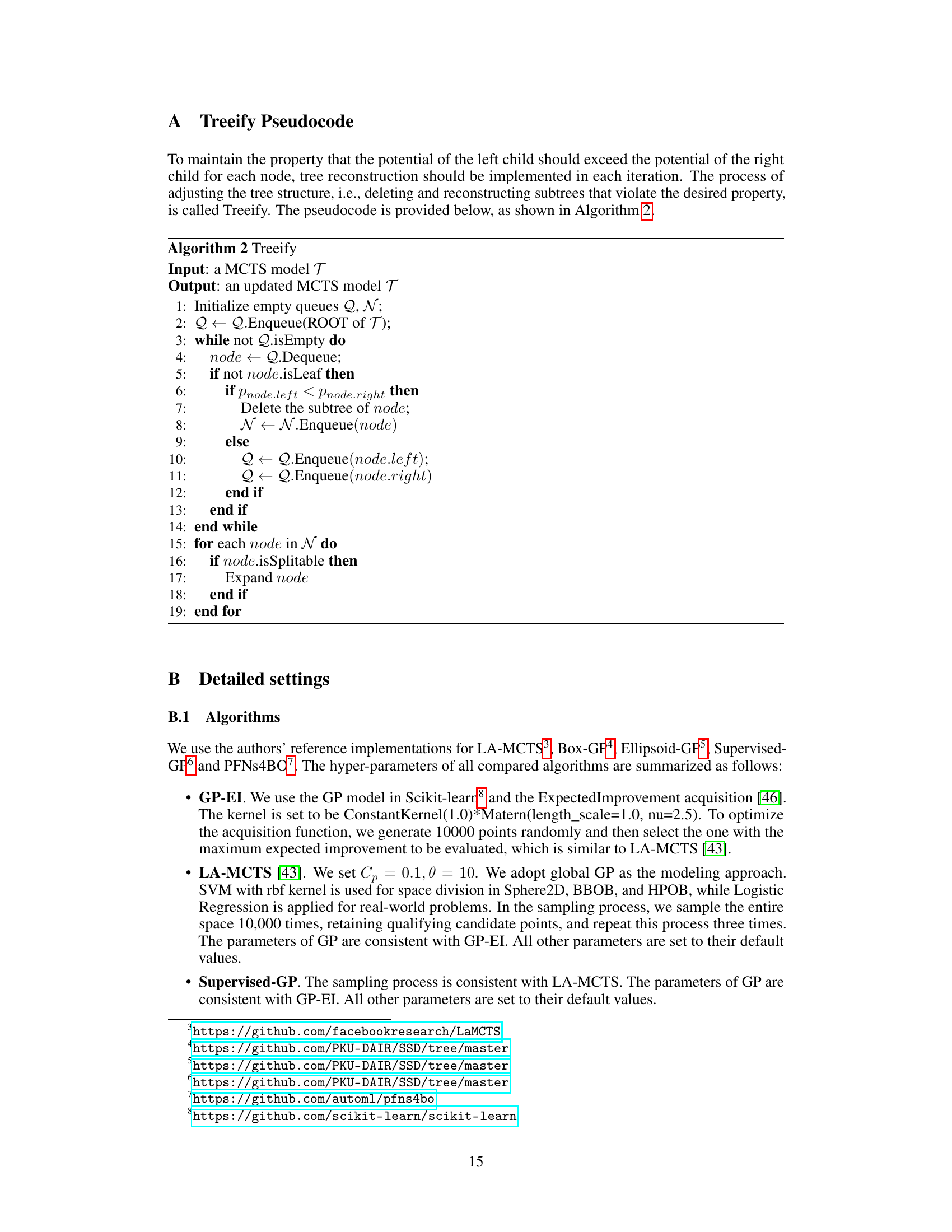

The figure shows the performance comparison of MCTS-transfer against other algorithms (GP, LA-MCTS, Box-GP, Ellipsoid-GP, Supervised-GP, and PFN) on the BBOB benchmark. It presents the evaluation results across five different BBOB functions (GriewankRosenbrock, Lunacek, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock, and SharpRidge), showcasing both ‘similar’ and ‘mixed’ transfer learning settings. The graphs illustrate the objective function values over the number of evaluations, providing insights into the convergence speed and performance of each method under varying conditions.

In-depth insights#

MCTS-Transfer:Core Idea#

MCTS-Transfer leverages the power of Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to enhance Bayesian Optimization (BO) by intelligently transferring knowledge from similar source tasks. Its core idea is an iterative process of dividing, selecting, and optimizing within a learned subspace. Initially, MCTS constructs a search space representation using data from source tasks, forming a tree structure where nodes signify subspaces. During optimization, MCTS selects a node (subspace) using an Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) approach, balancing exploration and exploitation. BO is then applied within the chosen subspace. Crucially, MCTS-Transfer dynamically adjusts weights assigned to source tasks based on their similarity to the current target task, allowing it to prioritize relevant information. This adaptive weighting, coupled with the iterative refinement of the search space through MCTS, enables efficient identification and utilization of valuable information from source tasks, resulting in faster optimization for the target task. The algorithm’s flexibility is a key strength, as it does not rely on a fixed partitioning of the search space but instead dynamically refines its focus as more data becomes available.

Adaptive Search Space#

An adaptive search space in the context of black-box optimization is a crucial concept that dynamically adjusts its exploration strategy based on the information gathered during the optimization process. Instead of relying on a fixed, predefined search space, which might overlook promising areas or waste resources on unfruitful regions, an adaptive approach intelligently refines the search area. This could involve techniques such as iteratively partitioning the space, focusing computational effort on more promising sub-regions, or adjusting the dimensionality of the space depending on the problem’s characteristics. The effectiveness of an adaptive search space is primarily determined by its ability to balance exploration and exploitation, efficiently identifying and exploiting regions containing high-quality solutions while simultaneously exploring less-explored areas. Successful strategies often incorporate feedback mechanisms that analyze the optimization landscape, enabling the algorithm to learn from past evaluations and guide future searches. Incorporating prior knowledge and transfer learning can further enhance adaptation by leveraging information from similar tasks, leading to improved efficiency and effectiveness.

Source Task Weighting#

Source task weighting is a crucial aspect of transfer learning in Bayesian Optimization, particularly when dealing with heterogeneous datasets. The core idea is to assign weights to different source tasks based on their relevance to the target task. This weighting mechanism is essential for effective knowledge transfer, allowing the algorithm to prioritize information from similar tasks while downweighting less relevant ones. Adaptive weighting strategies, where weights are adjusted dynamically during optimization, are particularly beneficial as they allow the model to refine its understanding of task similarity over time. Determining appropriate weights can involve various approaches, from simple heuristics based on distance metrics in the search space to more sophisticated methods that leverage kernel functions or meta-learning techniques. The choice of weighting scheme significantly impacts the model’s performance, influencing both its convergence speed and solution quality. A well-designed weighting mechanism is key to avoiding negative transfer, where information from dissimilar tasks hinders performance, and maximizing the beneficial impact of transfer learning.

Experimental Evaluation#

A robust experimental evaluation section should meticulously detail the methodology, ensuring reproducibility. It should clearly define the metrics used to assess performance, such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, or AUC, depending on the specific task. Datasets utilized must be thoroughly described, including size, characteristics, and any preprocessing steps. The evaluation should involve a rigorous comparison against relevant baselines and state-of-the-art methods. Statistical significance testing should be employed to validate the observed improvements, addressing potential biases and random variation. Furthermore, error bars or confidence intervals should be included in the results presentation to provide a clear sense of uncertainty. The analysis should interpret the experimental findings thoroughly, linking them back to the theoretical claims made in the paper and addressing any unexpected or anomalous outcomes. Ablation studies that systematically remove components to measure their individual contributions are valuable. Finally, it is essential to provide a clear and concise overview of the results, summarizing key findings and their implications within the broader context of the research field.

Future Work: Heterogeneous Transfer#

Future work in heterogeneous transfer learning for Bayesian Optimization (BO) presents exciting challenges and opportunities. Extending current homogeneous transfer methods, which assume similar source and target tasks, to handle the heterogeneity inherent in real-world problems is crucial. This involves developing techniques to effectively leverage knowledge from diverse source tasks, potentially with varying dimensions, data types, or optimization objectives. Addressing the task similarity issue is paramount; robust methods are needed to accurately assess and quantify the relevance of different source tasks for the target optimization problem. Adaptive weighting strategies should be refined to dynamically adjust the contribution of each source task based on emerging information during the optimization process. Furthermore, research should focus on developing efficient algorithms that can handle the increased computational complexity associated with managing and processing diverse datasets. Novel approaches to subspace representation and transfer, beyond simple geometric methods, are needed to capture the complex relationships between heterogeneous tasks. Finally, comprehensive evaluation benchmarks and metrics are required to rigorously assess the effectiveness of heterogeneous transfer in diverse BO settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

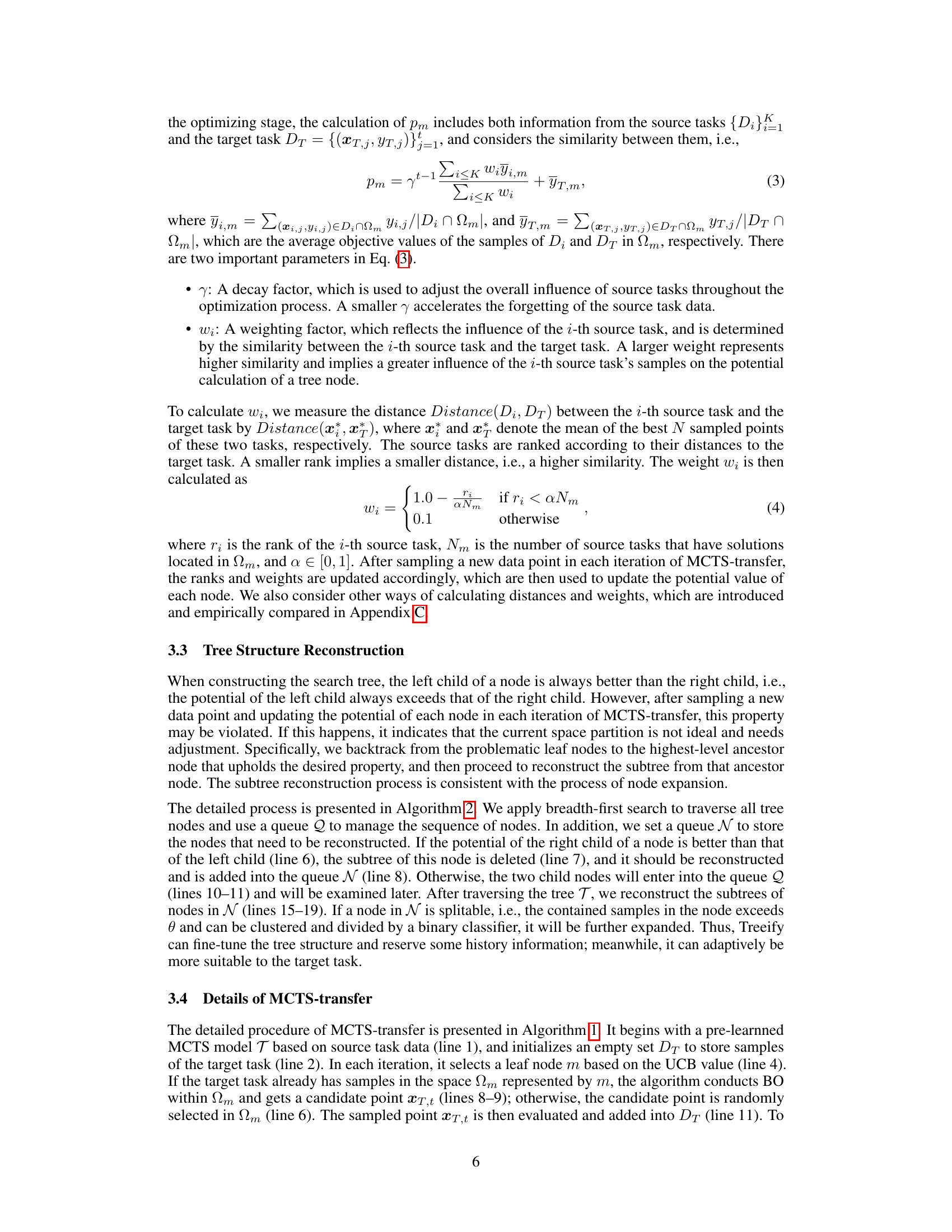

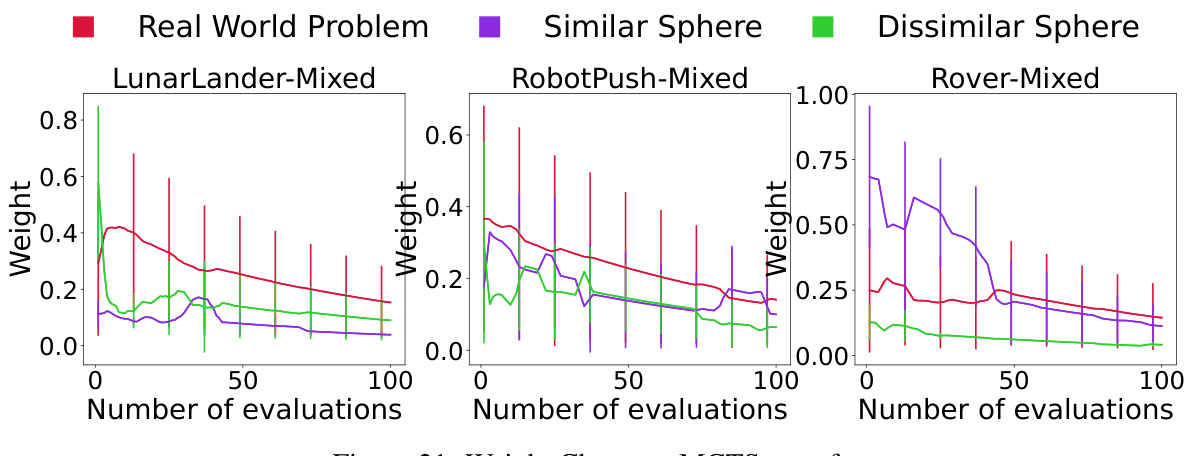

The figure compares the performance of MCTS-transfer with other search space transfer algorithms (Box-GP, Ellipsoid-GP, and Supervised-GP) on the Sphere2D problem. It shows the best value achieved by each algorithm over a certain number of evaluations in both mixed and dissimilar transfer settings. The right panel displays the weight change curves for the three source tasks, demonstrating MCTS-transfer’s ability to assign higher weights to more similar tasks.

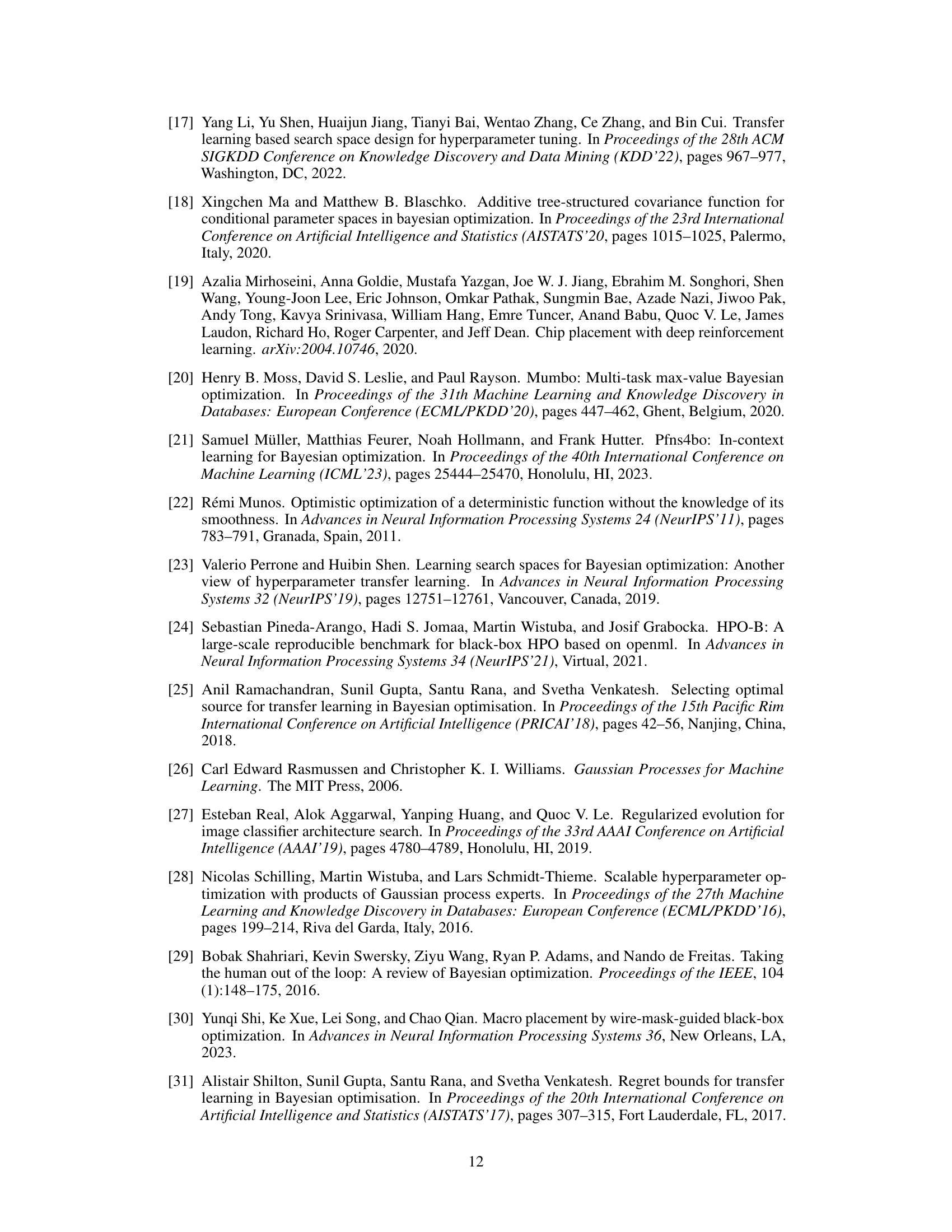

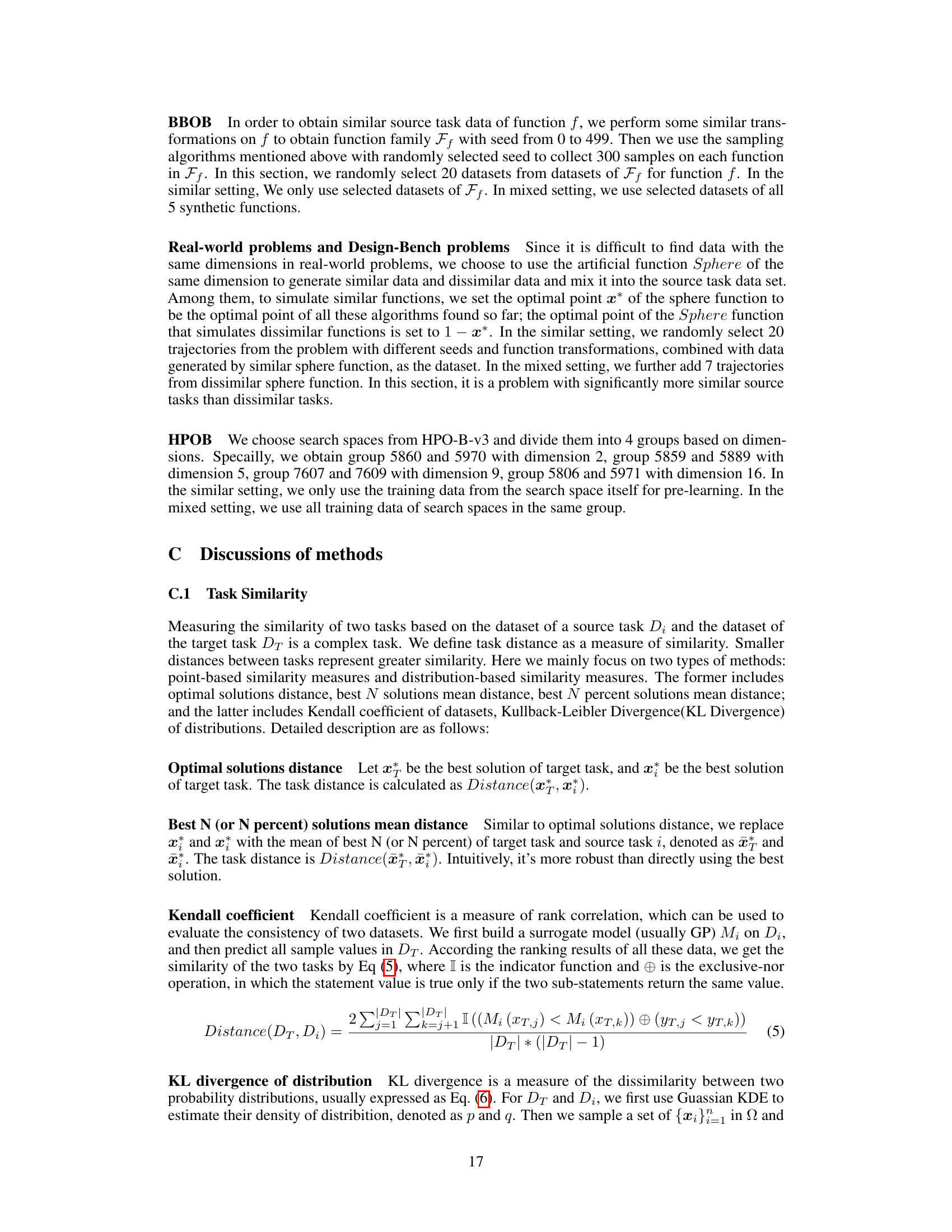

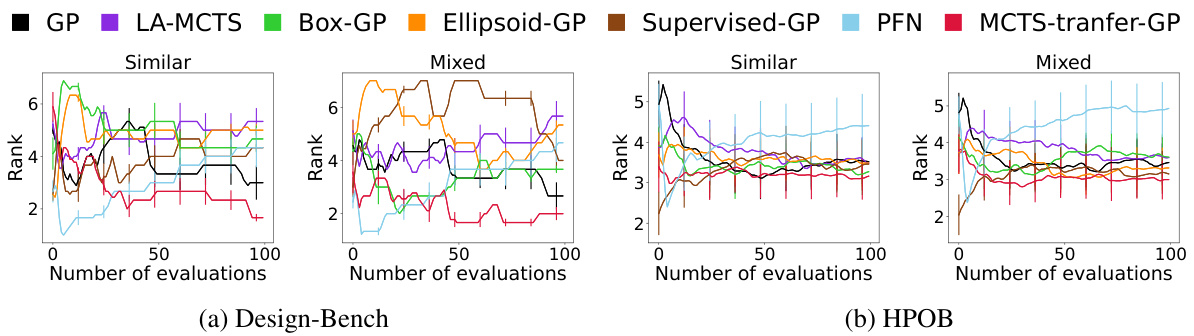

This figure compares the performance of MCTS-transfer against other algorithms (GP, LA-MCTS, Box-GP, Ellipsoid-GP, Supervised-GP, PFN) on both synthetic benchmark functions from BBOB and real-world problems. The graphs illustrate the rank of each algorithm over a certain number of evaluations, demonstrating MCTS-transfer’s superior performance, particularly in mixed transfer scenarios (where a combination of similar and dissimilar source tasks are used for pre-training). The results highlight the ability of MCTS-transfer to handle complex situations with varying degrees of task similarity.

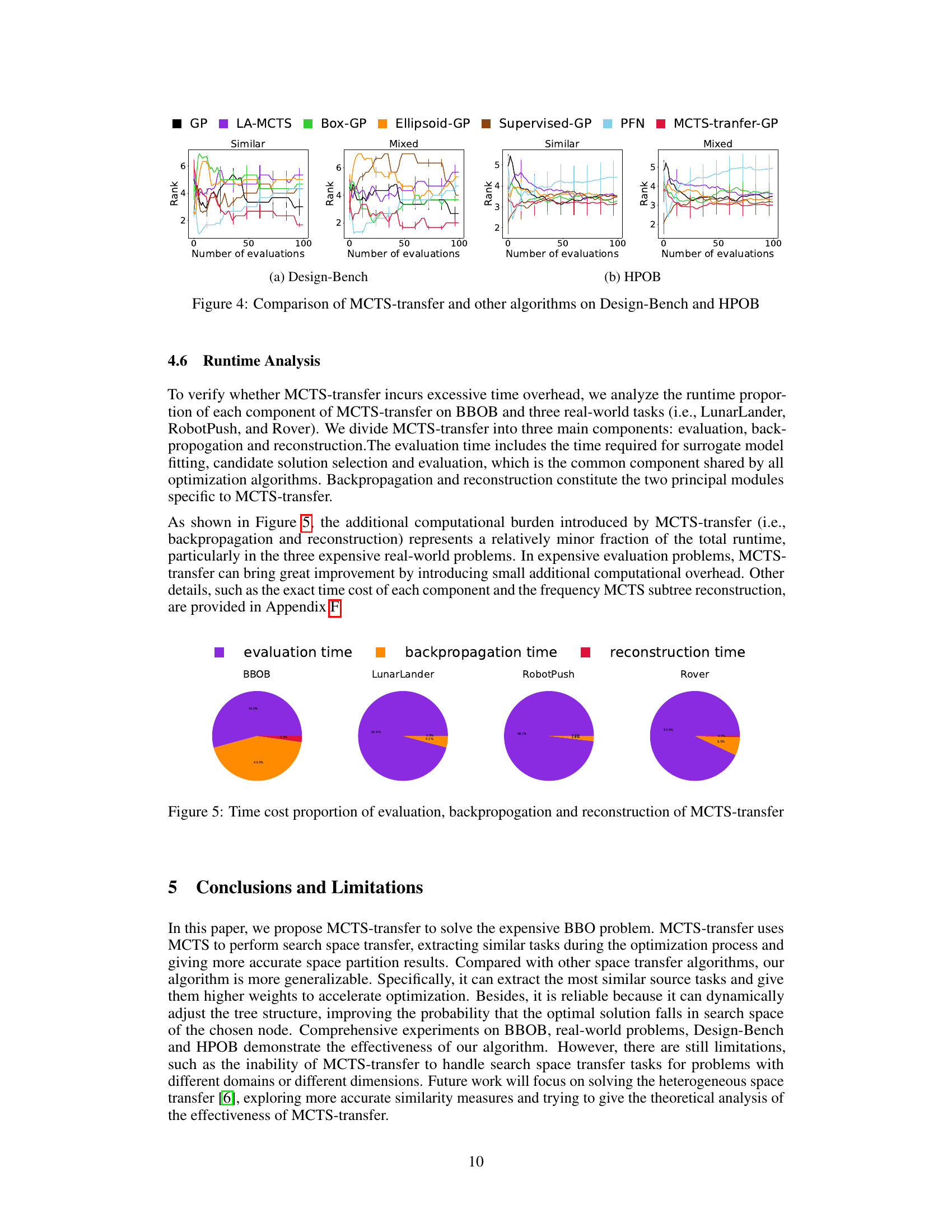

This figure compares the performance of MCTS-transfer against other algorithms (GP, LA-MCTS, Box-GP, Ellipsoid-GP, Supervised-GP, PFN) on Design-Bench and HPOB benchmarks, under both similar and mixed transfer learning settings. The plots show the mean rank of the algorithms over a series of evaluations. MCTS-transfer demonstrates competitive performance, particularly in the mixed transfer setting where it needs to handle less similar source tasks.

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of the MCTS-transfer algorithm. The pre-learning stage uses MCTS to build a tree structure by recursively dividing the search space based on source task data. Each node in the tree represents a subspace. The optimization stage then uses this pre-learned tree to initialize the search for the target task, iteratively selecting subspaces with high potential based on UCB values and refining the tree structure with new target task data.

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of the MCTS-transfer algorithm. The pre-learning stage uses MCTS to build a tree structure by recursively dividing the search space based on source task data. Each node in the tree represents a subspace. The optimization stage then uses this pre-learned tree to initialize the search for the target task. It iteratively selects subspaces based on an upper confidence bound (UCB) and then optimizes within the selected subspace before updating the tree based on new observations.

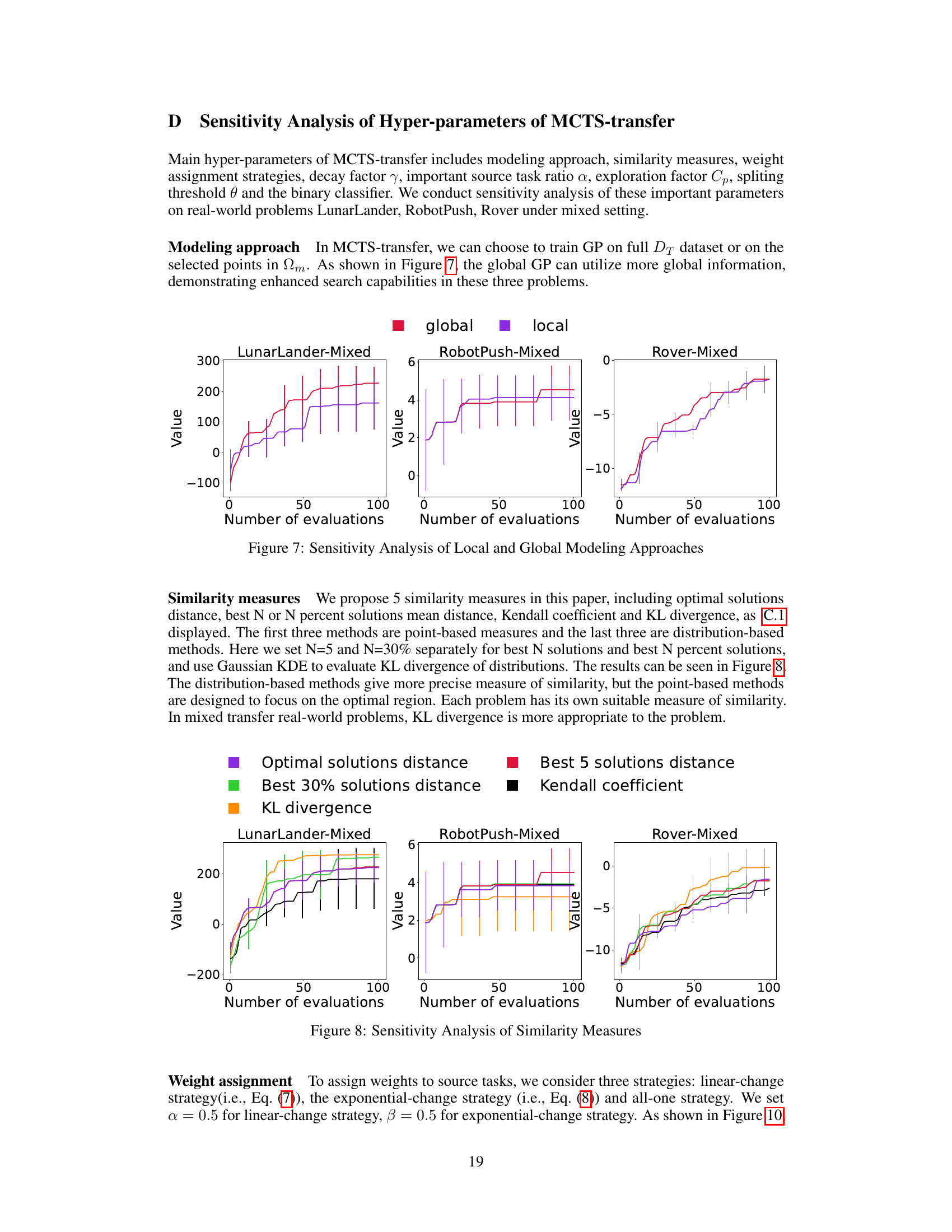

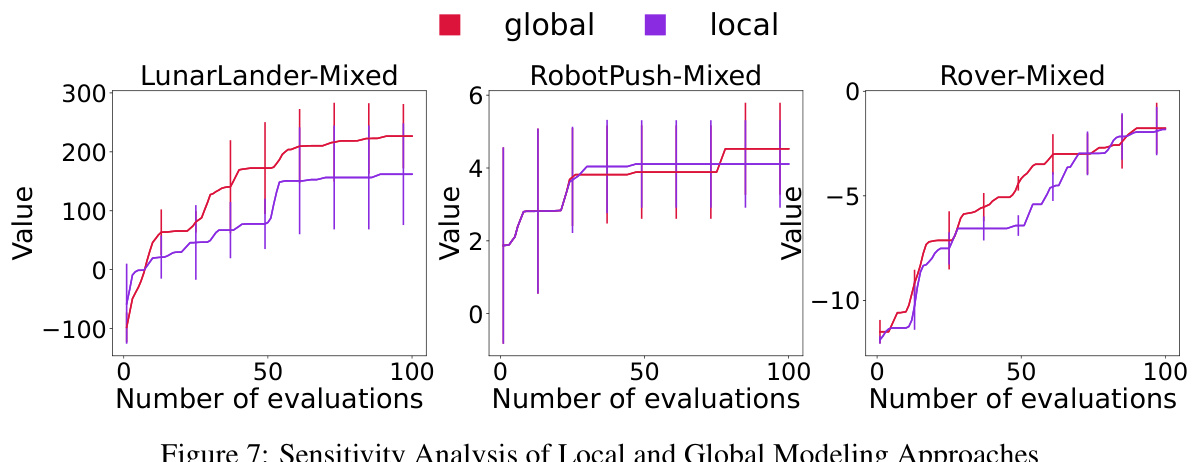

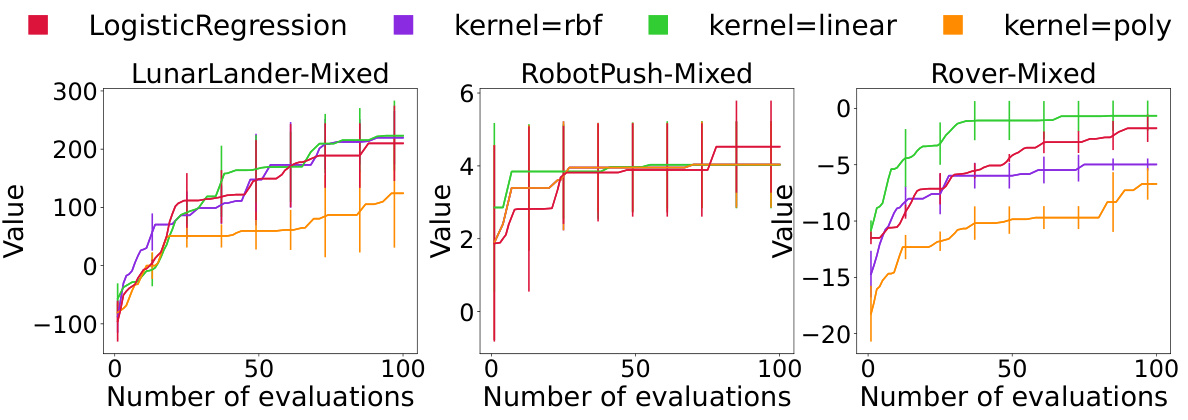

This figure presents a sensitivity analysis comparing the performance of using a global Gaussian Process (GP) model versus a local GP model within the MCTS-transfer algorithm. The analysis is performed on three real-world problems (LunarLander-Mixed, RobotPush-Mixed, and Rover-Mixed). The plots show the average objective value against the number of evaluations performed, with error bars indicating variability. The results show how the choice of global versus local modeling affects the optimization performance across different tasks.

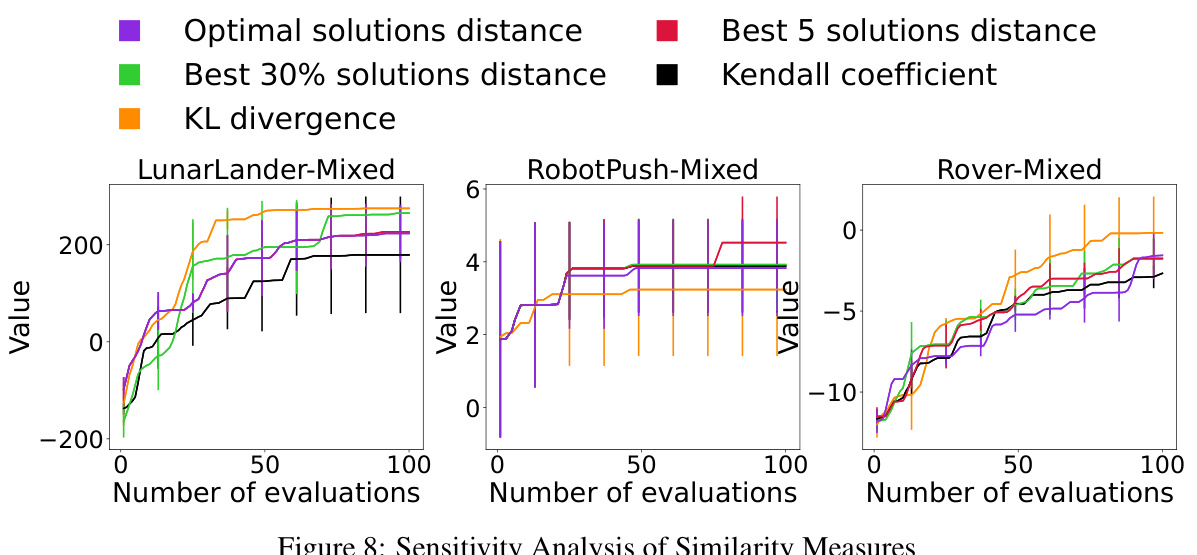

This figure displays the sensitivity analysis of five different similarity measures used in the MCTS-transfer algorithm. The measures are: Optimal solutions distance, Best 5 solutions distance, Best 30% solutions distance, KL divergence, and Kendall coefficient. The graph shows how the performance of the algorithm varies across three different real-world problems (LunarLander-Mixed, RobotPush-Mixed, and Rover-Mixed) depending on which similarity measure is selected. Each line represents a different measure, and the y-axis represents the objective function value obtained by the algorithm. The x-axis represents the number of evaluations performed. The comparison demonstrates the impact of the chosen similarity measure on the algorithm’s ability to effectively transfer knowledge from source tasks to a target task and optimize its performance.

The figure compares the performance of three different weight change strategies (linear, exponential, and all-one) across three real-world problems (LunarLander-Mixed, RobotPush-Mixed, and Rover-Mixed) using MCTS-transfer. The linear strategy shows relatively stable performance, while the exponential strategy leads to faster convergence initially but might under-utilize source task data. The all-one strategy demonstrates the ability to fully utilize information but is more sensitive to dissimilar data. The graph illustrates the best value obtained during optimization against the number of evaluations performed.

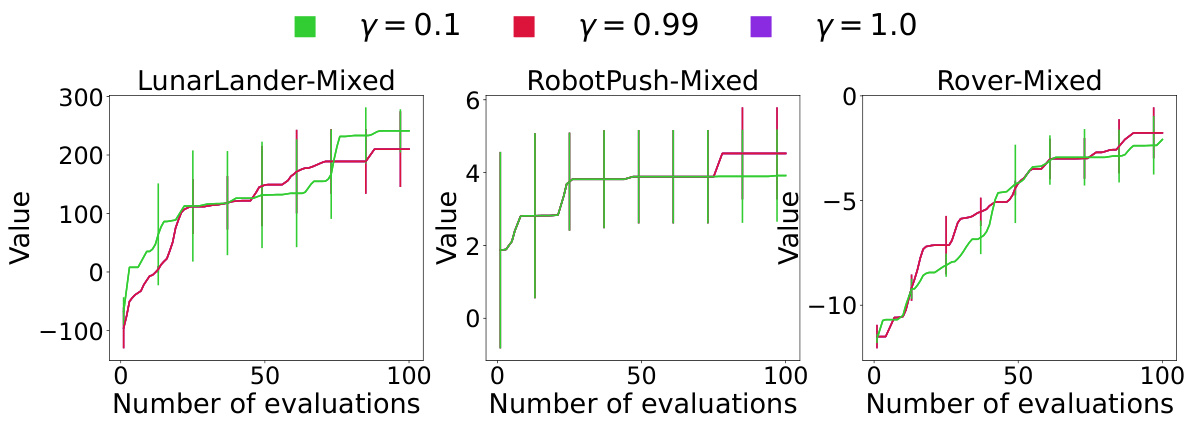

This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of the decay factor (γ) in MCTS-transfer on three real-world problems (LunarLander, RobotPush, and Rover) under mixed transfer settings. The decay factor controls the influence of source tasks on the node potential calculations. The results indicate that a decay factor of 0.99 and 1.0 leads to better performance compared to a factor of 0.1, suggesting that a moderate decay rate allows effective combination of information from source and target tasks to accelerate optimization.

The figure displays the sensitivity analysis of the important source task ratio α in the linear-change strategy. It shows how the performance of MCTS-transfer varies with different values of α on three real-world problems (LunarLander, RobotPush, and Rover) under mixed transfer settings. The results indicate that a balanced α value effectively utilizes information from both similar and dissimilar source tasks, achieving better overall performance.

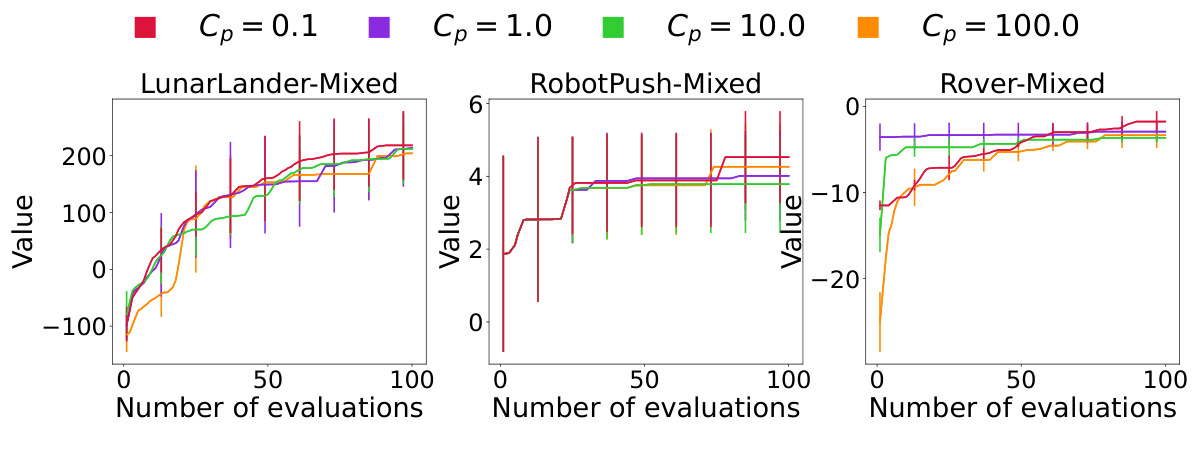

The figure shows the sensitivity analysis of the exploration factor Cp in MCTS-transfer on three real-world problems (LunarLander, RobotPush, and Rover) under mixed transfer settings. Different values of Cp (0.1, 1.0, 10.0, and 100.0) were tested, and the resulting performance (value) is plotted against the number of evaluations. Error bars represent variability in the results. The plot helps to understand how the exploration-exploitation balance (controlled by Cp) affects the optimization performance in different scenarios.

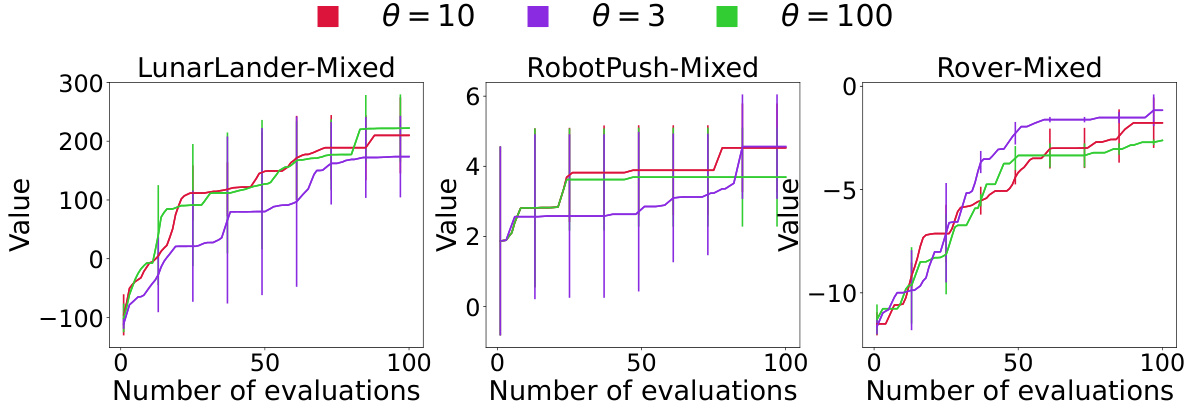

This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of the splitting threshold (θ) in MCTS-transfer on three real-world problems: LunarLander, RobotPush, and Rover. Three different values of θ (10, 3, and 100) are tested under a mixed transfer setting. The plots illustrate how the choice of θ impacts the performance of the algorithm in terms of the objective function value over the number of evaluations. A smaller θ leads to a deeper tree, potentially increasing computational cost but also allowing for a more refined search space partition. The results show the impact of this parameter on the algorithm’s convergence and exploration-exploitation balance.

This figure shows the sensitivity analysis of different binary classifiers used in the MCTS-transfer algorithm for dividing the search space. The three real-world problems, LunarLander, RobotPush, and Rover, are evaluated under mixed transfer settings. Different classifiers (Logistic Regression, SVM with rbf, linear, and polynomial kernels) are compared to determine their effectiveness in dividing the search space into ‘good’ and ‘bad’ clusters. The results indicate that Logistic Regression and SVM with a linear kernel generally provide superior search space partitioning.

This figure illustrates the workflow of the MCTS-transfer algorithm. The pre-learning stage uses MCTS to iteratively divide the search space into subspaces based on source task data, resulting in a tree structure. The optimization stage uses this pre-learned tree to iteratively select and optimize promising subspaces for the target task, adapting the tree structure dynamically during the optimization process based on newly sampled target task data.

The figure presents the performance comparison of MCTS-transfer against other baseline algorithms (GP, LA-MCTS, Box-GP, Ellipsoid-GP, Supervised-GP, and PFN) on three real-world problems: LunarLander, RobotPush, and Rover. The results are shown for both similar and mixed transfer settings. Each subfigure shows the optimization progress of the algorithms over a certain number of evaluations. It visualizes the objective function values achieved over time for each algorithm in each scenario, illustrating the relative performance of MCTS-transfer compared to the baselines in different transfer settings and the problem’s characteristics.

This figure illustrates the two main stages of the MCTS-transfer algorithm: pre-learning and optimization. The pre-learning stage uses a Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) to iteratively divide the search space based on source task data, creating a tree structure where each node represents a subspace. This tree serves as a warm start for the optimization stage. In the optimization stage, MCTS is used again to select a promising subspace for optimization, using the UCB (Upper Confidence Bound) value to guide the selection. The algorithm adaptively adjusts the search space partition based on newly generated target task data throughout the optimization process.

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of the MCTS-transfer algorithm. The pre-learning stage uses source task data to build a tree structure that partitions the search space. Each node in the tree represents a subspace. The optimization stage then uses this pre-learned tree to guide the search for the target task, iteratively selecting subspaces with high potential and refining the tree structure based on new observations. The UCB (Upper Confidence Bound) is used to balance exploration and exploitation during subspace selection.

This figure illustrates the two-stage process of the MCTS-transfer algorithm. The pre-learning stage uses MCTS to iteratively divide the search space into subspaces based on source task data. The resulting tree structure guides the optimization process in the second stage. In the optimization stage, MCTS is again used to select a promising subspace from the pre-learned tree. A Bayesian optimization algorithm is then applied to refine the search within this subspace. The process iteratively refines the search space and adapts it to the target task.

This figure illustrates the two main stages of the MCTS-transfer algorithm: pre-learning and optimization. The pre-learning stage uses source task data to build a tree structure by recursively clustering and classifying samples, resulting in a hierarchical representation of the search space. The optimization stage leverages this pre-learned tree to efficiently guide the search for the target task. The algorithm iteratively selects a leaf node based on its UCB value, optimizes within the corresponding subspace, and updates the tree structure dynamically based on new observations.

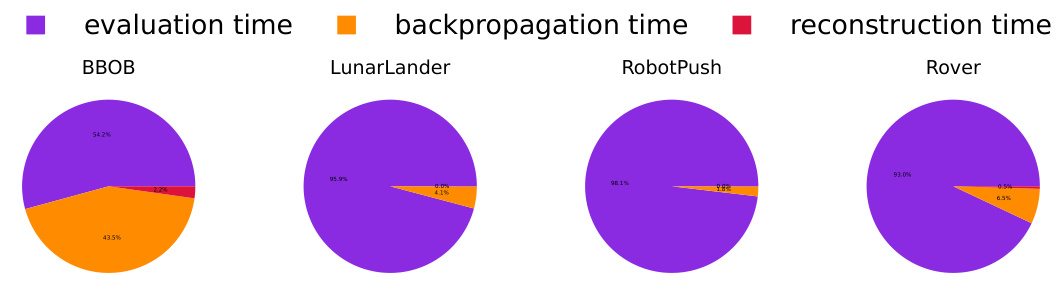

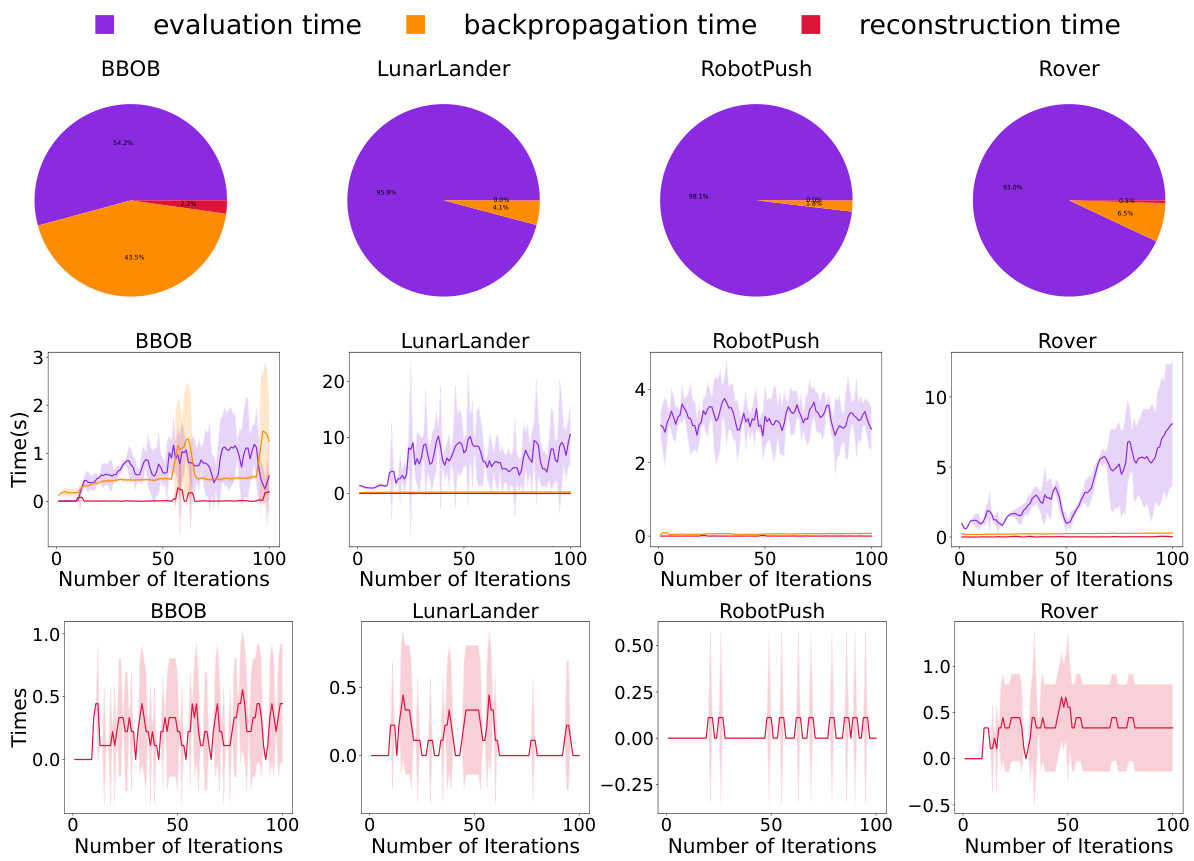

The figure displays the weight changes of three mixed real-world problems over 100 evaluations. The weights are assigned to source tasks (real-world problems, similar sphere, and dissimilar sphere) dynamically during the optimization process, reflecting the similarity between source tasks and the target task. The results show that the weights of real-world problems and similar sphere problems are higher than those of dissimilar sphere problems in most cases, even with inconsistencies in initialization. This demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to prioritize similar source task data, leading to more accurate node potential evaluation and search space partition.

Full paper#