↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Operator learning, crucial in computational science, typically focuses on Hilbert spaces. However, many real-world problems involve operators mapping between Banach spaces, presenting a significant challenge. This paper addresses the limitations of existing methods by focusing on learning holomorphic operators—a class with wide applications—between Banach spaces.

This research introduces a novel deep learning (DL) methodology combining approximate encoders/decoders with feedforward DNNs. The method achieves optimal generalization bounds, meaning it performs as well as any other method up to logarithmic factors. Crucially, the proposed DNN architectures’ width and depth depend only on the training data size, not the operator’s regularity, showing their adaptability and efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in scientific computing and machine learning. It provides optimal deep learning solutions for a challenging class of problems: learning operators between Banach spaces, which are common in many applications. The optimal generalization bounds and problem-agnostic DNN architectures offer significant advancements. Further research may explore the practical implications of these findings for various applications.

Visual Insights#

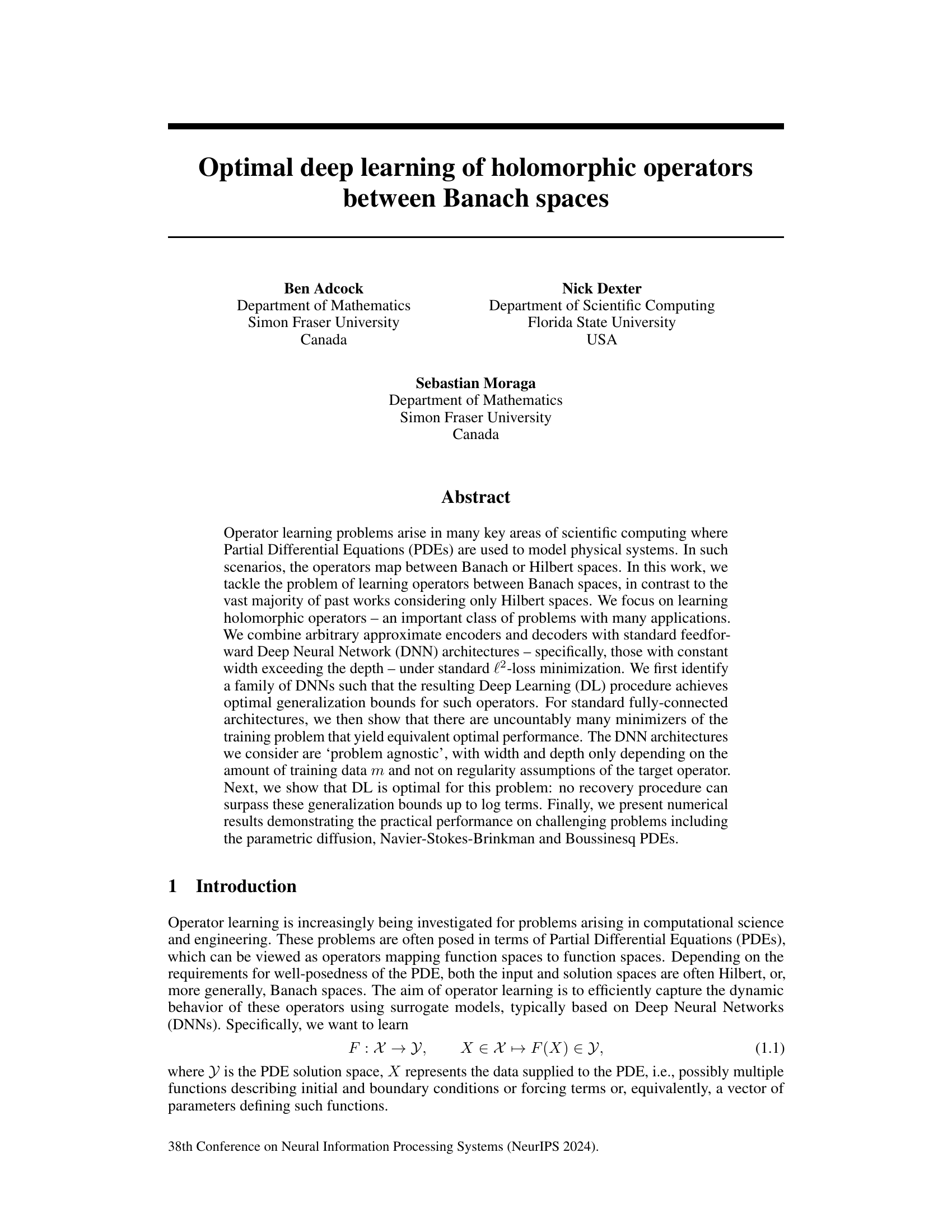

This figure shows the performance of different DNN architectures in approximating the solution operator of the parametric elliptic diffusion equation. The error is measured using the average relative L(X;Y)-norm and plotted against the number of training samples (m). The results are shown for both affine and log-transformed diffusion coefficients, with different parametric dimensions (d = 4 and d = 8). Each line represents a different DNN architecture, showing how the error decreases as the number of training samples increases.

In-depth insights#

Banach Space DL#

The concept of “Banach Space Deep Learning (DL)” signifies a significant extension of traditional DL methods, which typically operate within Hilbert spaces. Moving to Banach spaces allows for the consideration of a broader class of problems, encompassing those involving operators that map between function spaces with less restrictive regularity assumptions. This is crucial as many real-world problems, particularly in areas like fluid dynamics and partial differential equations, are naturally represented in Banach spaces. The research likely explores the theoretical underpinnings of DL in this more general setting, investigating questions of approximation accuracy, generalization bounds, and computational complexity. Challenges would involve adapting optimization algorithms and network architectures to handle the nuances of Banach spaces’ lack of inner product structure. Furthermore, the research likely demonstrates the practical viability and potential advantages of this approach via numerical experiments, possibly on complex, high-dimensional datasets where the benefits of Banach space DL would be most evident. This expands the applicability of DL to previously intractable problems and would have significant implications in scientific computing and machine learning.

Holomorphic Ops#

The concept of “Holomorphic Ops” in the context of the provided research paper likely refers to the application of deep learning techniques to learn and approximate holomorphic operators. These operators, characterized by their complex differentiability, are prevalent in various scientific computing applications, particularly those involving partial differential equations (PDEs). The paper’s focus on Banach spaces, rather than solely Hilbert spaces, is significant, as it broadens the applicability of deep learning to a wider class of operator learning problems. The core idea appears to be leveraging the properties of holomorphic functions, which allow for efficient approximation using deep neural networks (DNNs) and enabling the derivation of optimal generalization bounds. The paper likely investigates the theoretical guarantees of this approach, proving that deep learning can achieve near-optimal results with specific DNN architectures, offering problem-agnostic solutions and avoiding potential issues related to parameter complexity or regularity constraints. Numerical experiments on challenging PDEs demonstrate the practical effectiveness of this approach to holomorphic operator learning.

DNN Architecture#

The paper investigates the optimal deep neural network (DNN) architecture for learning holomorphic operators between Banach spaces. A key finding is that DNN width is more crucial than depth, with optimal generalization bounds achieved when the width exceeds the depth. The architectures are designed to be ‘problem-agnostic,’ meaning their width and depth depend only on the training data size and not on the operator’s regularity assumptions. This contrasts with many existing approaches which rely heavily on problem-specific architectures. The authors show that fully-connected DNNs with sufficient width can achieve the same optimal generalization bounds as a more specialized, less practical architecture, suggesting that standard DNNs are suitable for operator learning in Banach spaces. However, a challenge presented is the existence of uncountably many DNN minimizers that yield equivalent performance, emphasizing the complexity of the optimization landscape.

Generalization Bounds#

Generalization bounds in deep learning are crucial for understanding a model’s ability to generalize from training data to unseen data. This paper focuses on deriving generalization bounds for deep learning of holomorphic operators between Banach spaces. The significance lies in tackling operator learning problems beyond the typical Hilbert space setting, opening up applications to more complex PDEs. The authors demonstrate the existence of DNN architectures that achieve optimal generalization bounds up to log terms, meaning the error decays algebraically with the amount of training data. A key contribution is the analysis of fully-connected architectures, showcasing that many minimizers of the training problem yield equivalent performance, highlighting robustness and potential for efficient learning. Importantly, the results establish the optimality of deep learning for this problem, showing that no other procedure can surpass these bounds. The paper combines theoretical analysis with numerical experiments, validating the findings on various challenging PDEs. However, the assumptions made, especially those related to holomorphy and the encoder-decoder accuracy, limit the applicability of the results to certain types of operators and learning scenarios. Future work could explore relaxing these assumptions and extending the results to wider classes of operators and PDEs.

Future Work#

The authors acknowledge several avenues for future research. Relaxing the holomorphy assumption is crucial for broader applicability. Exploring operators lacking this strong condition, while maintaining optimal generalization bounds, would significantly expand the framework’s utility. Investigating the role of the DNN architecture more fully is warranted, particularly concerning the existence of multiple minimizers. Further work should assess whether all minimizers yield equivalent optimal performance or if specific architectures are superior. Developing more efficient training algorithms is another important area; the present techniques, though effective, could benefit from improvements to reduce training times and computational resource needs. Finally, addressing the limitations of the Banach space analysis would increase the theoretical understanding and facilitate applications beyond Hilbert spaces, potentially leading to broader applications in various areas of computational science and engineering.

More visual insights#

More on figures

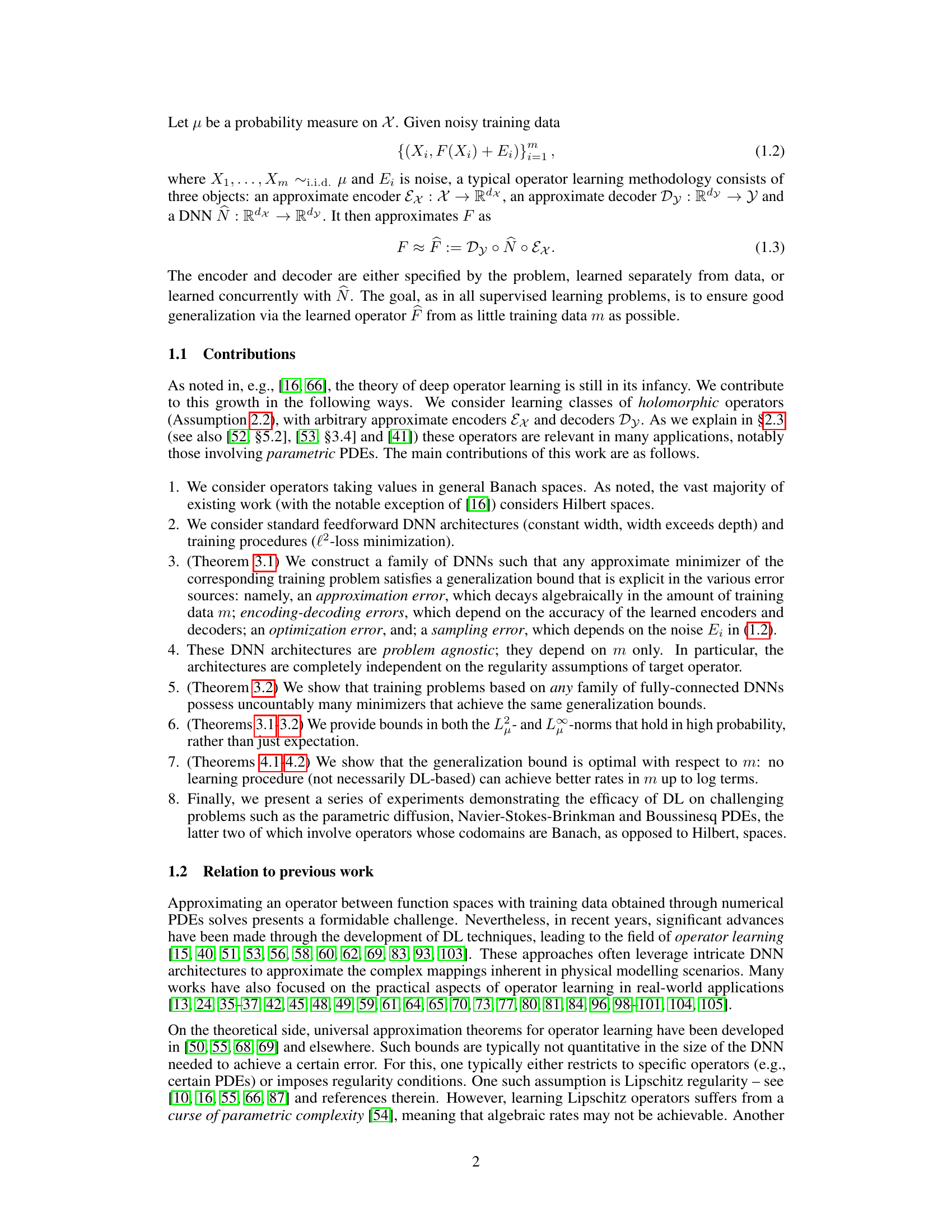

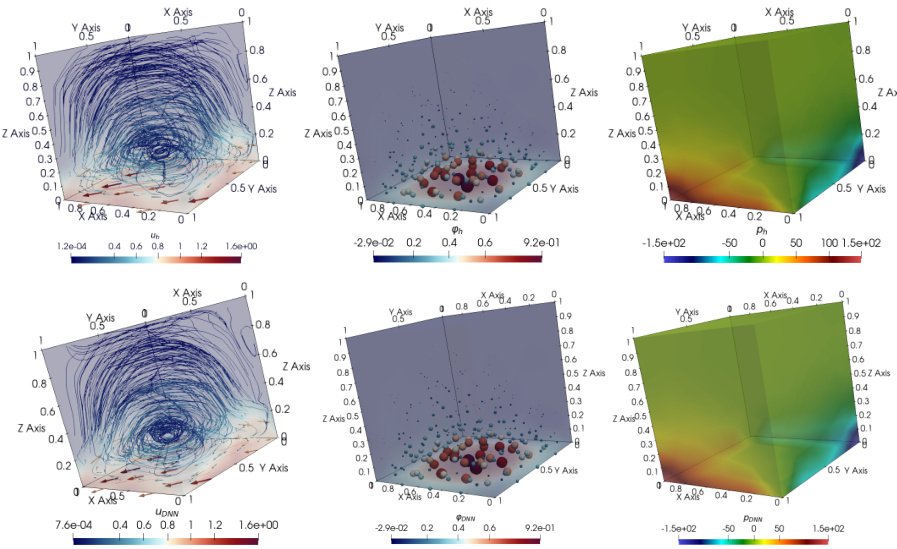

This figure shows the average relative L(X;Y)-norm error for different deep neural network (DNN) architectures in approximating the velocity field (u) of the parametric Navier-Stokes-Brinkman (NSB) equations. The results are shown for different numbers of training samples (m) and for both affine and log-transformed diffusion coefficients. The plot includes error bars to show variability and a reference line indicating a rate of m⁻¹. A similar figure (Figure 7) shows the same results, but for the pressure component (p).

This figure compares the performance of different DNN architectures on approximating the temperature field (φ) of the Boussinesq equation. It shows the average relative L2 error versus the number of training samples (m) for various DNNs with different activation functions (ELU, ReLU, tanh) and sizes (4x40, 10x100). The results are shown for both affine and log-transformed diffusion coefficients and two parametric dimensions (d=4 and d=8). An additional parametric dependence in the thermal conductivity tensor (K) is also considered in this example.

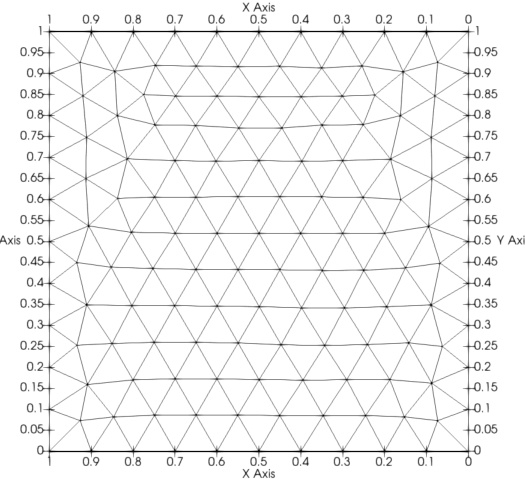

This figure shows the domain (Ω) and the finite element mesh used in the numerical experiments for the parametric elliptic diffusion equation. The domain is a unit square, and the mesh is a regular triangulation consisting of triangles.

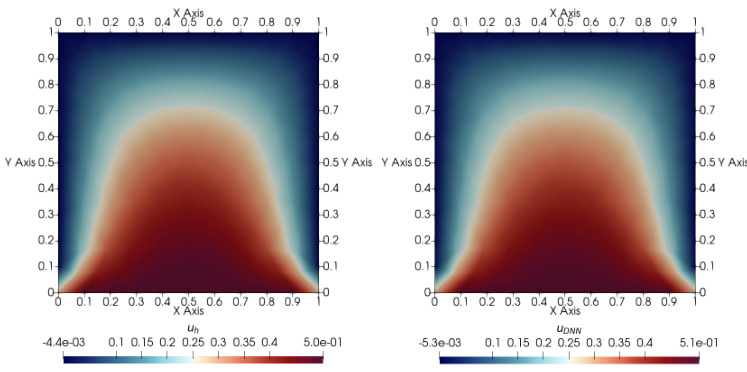

This figure compares the solution of the parametric Poisson equation (B.9) generated by the FEM solver and the ELU 4x40 DNN approximation. The left plot shows the solution from the FEM solver, while the right plot shows the DNN approximation after 60,000 training epochs with 500 training samples. Both plots illustrate the solution u(x) for a specific parameter set (1,0,0,0), using an affine coefficient (a1,d) and a parametric dimension d=4. The total degrees of freedom used in the FEM discretization is 2622.

This figure compares the solution of the parametric Poisson problem (B.9) obtained using a Finite Element Method (FEM) solver against the solution obtained using an ELU 4x40 Deep Neural Network (DNN). The DNN was trained on 500 sample points. The figure displays both solutions for a specific parameter set (x = (1,0,0,0)). The left panel shows the FEM solution, while the right panel shows the DNN approximation. This visualization helps assess the accuracy of the DNN in approximating the FEM solution for the given problem.

This figure compares the average relative L(X;Y)-norm error for different DNN architectures (4x40 and 10x100 with ReLU, ELU, and tanh activations) applied to the parametric Navier-Stokes-Brinkman (NSB) equations. The error is plotted against the number of training samples (m). Two parametric dimensions (d=4 and d=8) and two diffusion coefficients (affine and log-transformed) are considered. The results show that ELU and tanh DNNs generally outperform ReLU architectures. A separate figure (Figure 7) provides corresponding results for the pressure component (p).

This figure compares the average relative L2 error versus the number of training samples (m) for different DNN architectures in solving the parametric elliptic diffusion equation. It showcases the performance of various DNNs (with different activation functions and sizes) using both affine and log-transformed diffusion coefficients with varying parametric dimensions (d=4 and d=8). The results illustrate the impact of DNN architecture and coefficient type on the learning outcome.

The figure shows the average relative L²(X;Y) error versus the number of training samples (m) for different DNN architectures (ELU, ReLU, tanh) in approximating the temperature component of the solution of a parametric Boussinesq equation. Two parametric dimensions (d = 4, 8) and two types of diffusion coefficients (affine and log-transformed) are considered. The results demonstrate the performance of the different DNN architectures and the effect of increasing the number of training samples on the error, providing insights into the convergence rates.

Full paper#