↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many modern machine learning applications involve incorporating the solution of optimization problems within the learning process. This often requires differentiating through optimization layers which can be computationally expensive. Current methods rely heavily on implicit differentiation, which necessitates costly computations on Jacobian matrices, making them inefficient for large-scale problems.

BPQP addresses these issues by reformulating the backward pass as a simplified quadratic programming problem. This reformulation allows for the use of efficient first-order optimization algorithms, drastically reducing computational cost and improving overall efficiency. Experiments show that BPQP is significantly faster than existing methods across various optimization problems and datasets, highlighting its potential for enhancing end-to-end learning in large-scale applications.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents BPQP, a novel framework for efficient end-to-end learning, significantly improving the speed of differentiable optimization layers. It offers flexibility in solver choice and adaptability as solver technology evolves, paving the way for more efficient and scalable applications of deep learning in diverse scenarios involving large-scale datasets and numerous constraints.

Visual Insights#

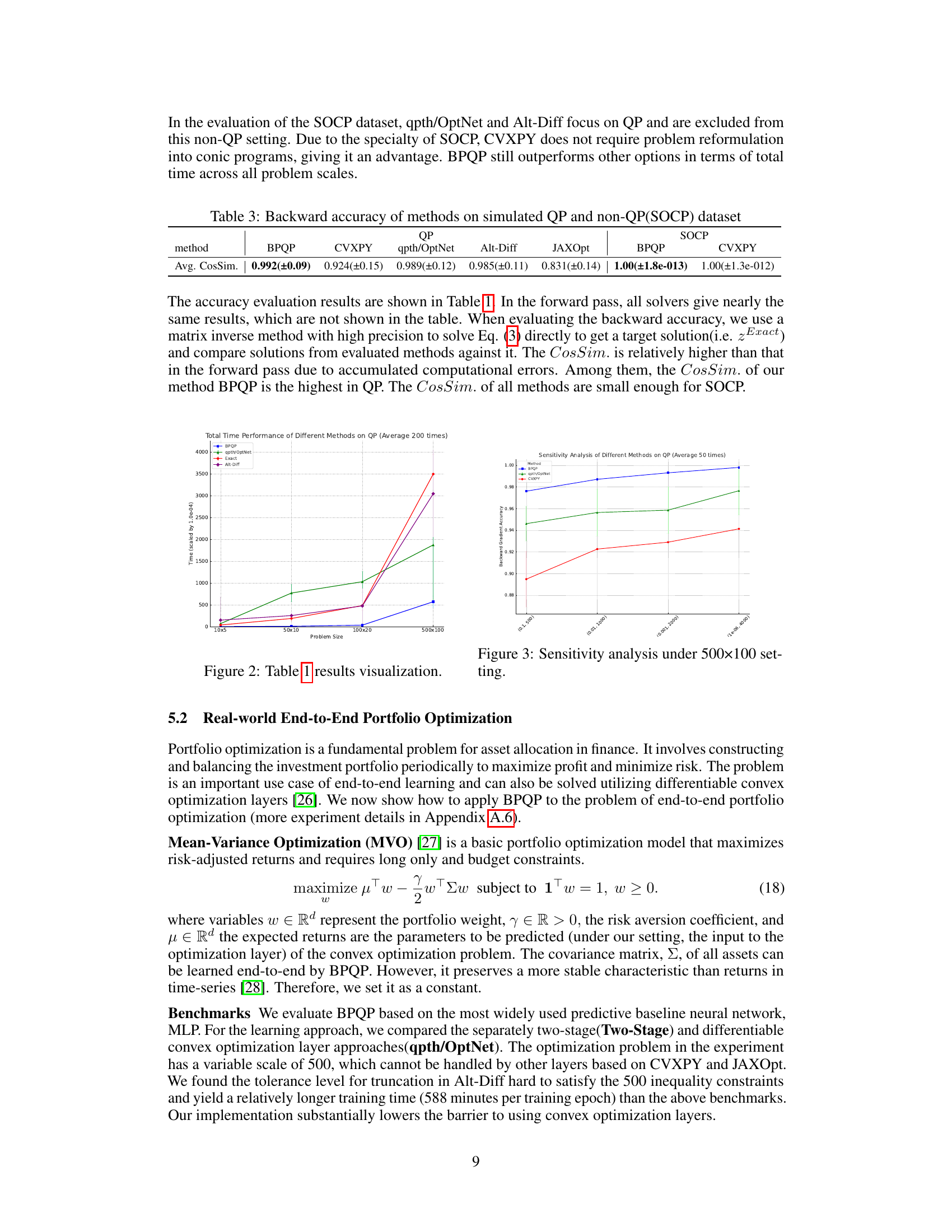

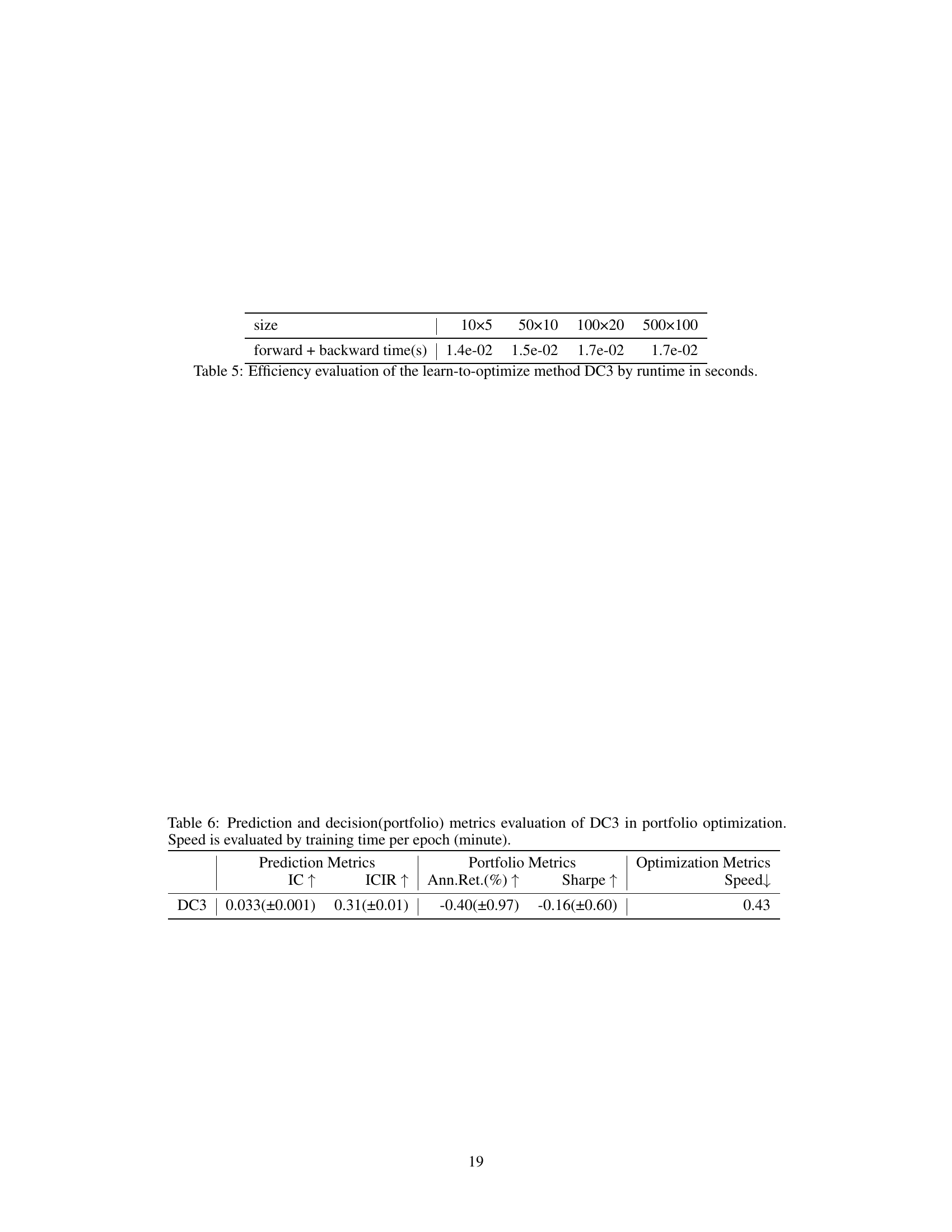

This figure illustrates the learning process of the BPQP framework. The forward pass solves a convex optimization problem to produce an optimal solution z*, given inputs y from the preceding layer. The backward pass, crucial for end-to-end learning, is simplified and decoupled by reformulating it as a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem, thus enabling efficient gradient calculation. The use of efficient first-order solvers for both the forward and backward passes speeds up the overall training process.

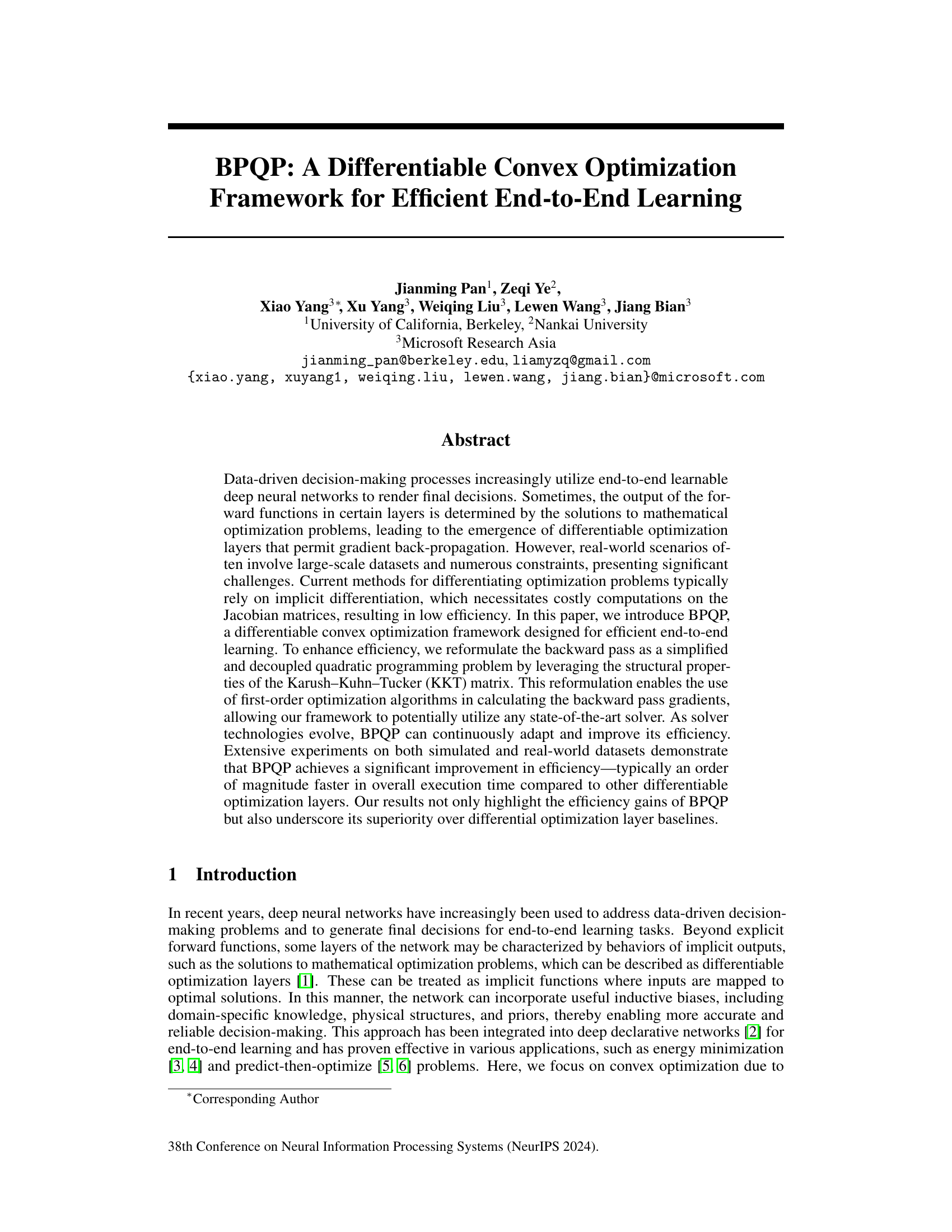

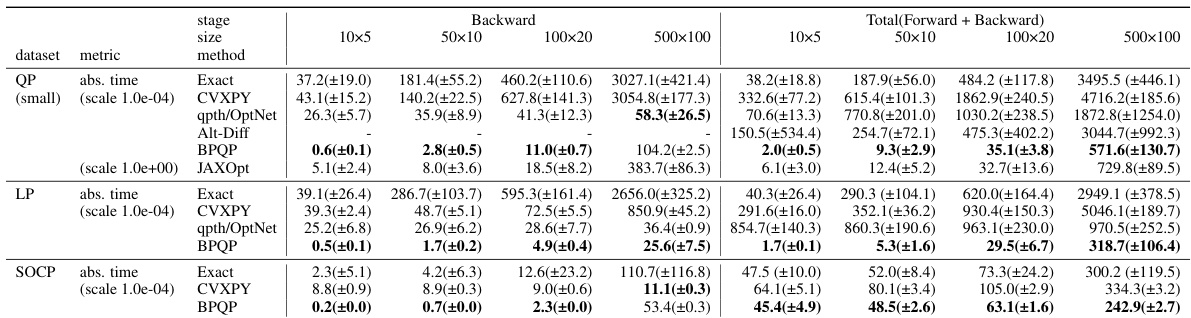

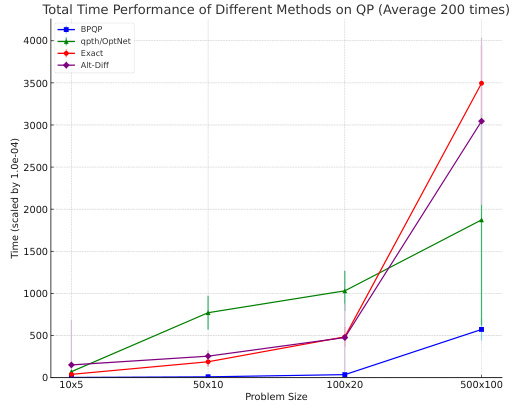

This table presents the efficiency comparison of different optimization methods (Exact, CVXPY, qpth/OptNet, Alt-Diff, BPQP, and JAXOpt) on three datasets (QP, LP, and SOCP) with varying problem sizes (10x5, 50x10, 100x20, 500x100). The runtime in seconds for forward, backward, and total processes are shown. Lower numbers indicate better performance. The table allows for a direct comparison of the efficiency gains of BPQP against state-of-the-art methods in solving large-scale convex optimization problems.

In-depth insights#

BPQP Framework#

The BPQP framework presents a novel differentiable convex optimization approach for efficient end-to-end learning. Its core innovation lies in reformulating the backward pass as a simplified quadratic programming (QP) problem, decoupling it from the forward pass and enabling the use of efficient first-order solvers. This design choice significantly improves computational efficiency, often achieving an order of magnitude speedup compared to existing methods. The flexibility to employ various QP solvers further enhances adaptability and potential for optimization as solver technology advances. While focused on convex problems, the framework’s theoretical underpinnings suggest potential applicability to certain non-convex scenarios through careful adaptation. The framework’s efficiency gains are empirically validated across diverse datasets, showcasing its practicality and potential impact on large-scale machine learning applications requiring differentiable optimization layers.

KKT Reformulation#

The Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions are central to optimization problems, providing necessary and sufficient conditions for optimality. A key challenge in applying end-to-end learning to optimization problems is efficiently computing gradients during backpropagation. KKT reformulation addresses this by transforming the computationally expensive process of implicit differentiation of the KKT system into a more tractable form. This might involve simplifying the KKT matrix structure, for instance, by leveraging sparsity or exploiting problem-specific characteristics. The goal is to create a simplified quadratic programming (QP) problem or a similar structured optimization problem whose solution efficiently yields the gradients needed for backpropagation. This reformulation is crucial for enabling efficient end-to-end training, significantly speeding up the learning process and allowing the method to scale to larger problems which was not previously possible.

Efficient QP Solver#

An efficient QP (Quadratic Programming) solver is crucial for the effectiveness of the proposed differentiable convex optimization framework. The paper highlights the importance of decoupling the forward and backward passes, enabling the use of specialized QP solvers without the constraints of differentiability in both phases. This decoupling, achieved through a novel reformulation of the backward pass as a simplified QP, is a key innovation. The choice of solver is flexible, potentially allowing for significant efficiency gains by adapting to specific problem structures. The use of first-order optimization algorithms is emphasized, suggesting scalability to large-scale problems. The paper’s experimental results demonstrate significant speed improvements compared to alternative approaches, highlighting the efficiency benefits of this design choice and showcasing the framework’s adaptability as solver technology progresses.

Empirical Analysis#

A robust empirical analysis section should present comprehensive results that thoroughly validate the claims made in the paper. It needs to go beyond simply reporting metrics; instead, it should delve into the significance of the findings, providing insights into the practical implications of the research. The analysis should be rigorous, employing appropriate statistical methods to determine the statistical significance of the results and addressing potential confounding factors. Visualizations such as graphs and charts are crucial for making the results clear and accessible to the reader. Crucially, the authors should perform a thorough comparison with existing methods and demonstrate the proposed method’s superiority. This comparison should include a discussion of any limitations or weaknesses of competing approaches, and it should be clear why the proposed method is superior. Finally, the analysis should be reproducible, with detailed descriptions of the experimental setup, datasets, and procedures to ensure that other researchers can validate the claims made in the paper.

Future Extensions#

The paper’s core contribution is a novel differentiable convex optimization framework (BPQP) for efficient end-to-end learning, significantly accelerating computations compared to existing methods. Future work could explore several promising avenues. Extending BPQP to handle non-convex optimization problems is a key challenge and opportunity. While the current framework excels with convexity, many real-world problems are inherently non-convex. Strategies for adapting the backward pass, perhaps via approximations or specialized solvers, are needed. Another important direction is improving scalability. While BPQP demonstrated efficiency gains, further optimization is crucial for extremely large-scale datasets and complex problems. This could involve leveraging distributed computing, exploring more sophisticated QP solvers, or developing adaptive strategies to tackle the computational complexity of higher dimensional problems. Finally, expanding the scope of applications is warranted. While portfolio optimization showed significant benefits, exploring the efficacy of BPQP across a wider range of domains, such as control systems, signal processing, and reinforcement learning, would solidify its impact and identify potential limitations.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the BPQP framework’s learning process. The forward pass involves solving a convex optimization problem (using an arbitrary solver, with a first-order solver as the default) to obtain the optimal solution z*, given input y. The backward pass, crucial for end-to-end learning, is simplified to a decoupled Quadratic Programming (QP) problem using the structural properties of the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) matrix. This reformulation makes the backward pass significantly more efficient than traditional methods that directly solve the original KKT linear system and allows for flexibility in using efficient QP solvers. The decoupling of the forward and backward passes is a key aspect of BPQP’s performance gains.

This figure illustrates the learning process of the BPQP framework. The forward pass involves solving a convex optimization problem with input y to obtain the optimal solution z*. The backward pass is simplified by reformulating it as a quadratic programming (QP) problem, which is then solved using an efficient solver (ADMM, by default, is used but the framework can leverage other solvers). This decoupling of the forward and backward passes significantly reduces computational costs, enabling efficient end-to-end learning.

This figure illustrates the BPQP learning process. The forward pass uses an arbitrary solver to find the optimal solution (z*) to a convex optimization problem, given inputs (y) from the previous layer. The backward pass, instead of using computationally expensive methods like implicit differentiation on the Jacobian matrix, leverages the properties of the Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) matrix to reformulate the gradient calculation as a simplified quadratic programming (QP) problem. This allows for the use of efficient first-order optimization algorithms, significantly improving overall efficiency. The figure visually depicts this decoupling of the forward and backward passes and the simplified QP problem used in the backward pass.

More on tables

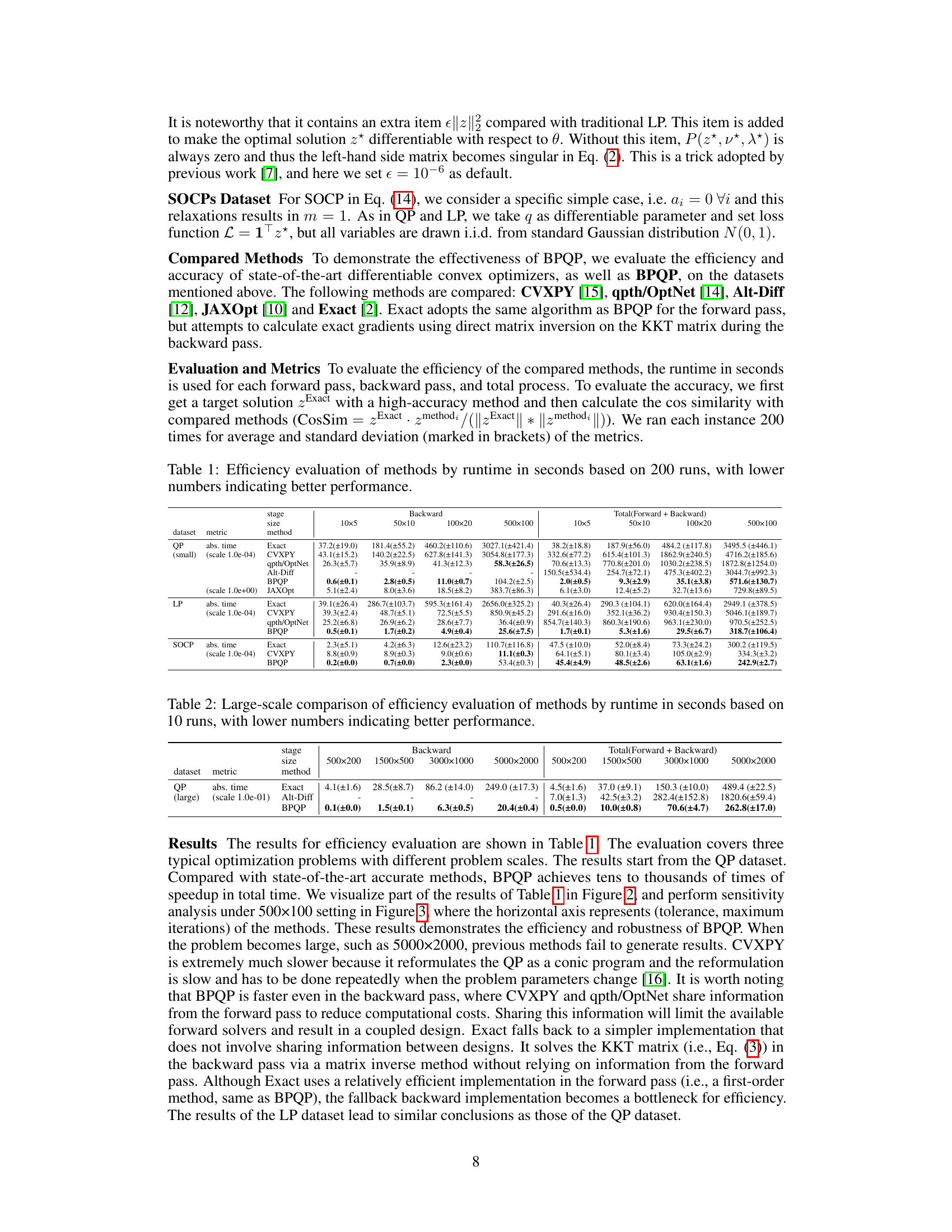

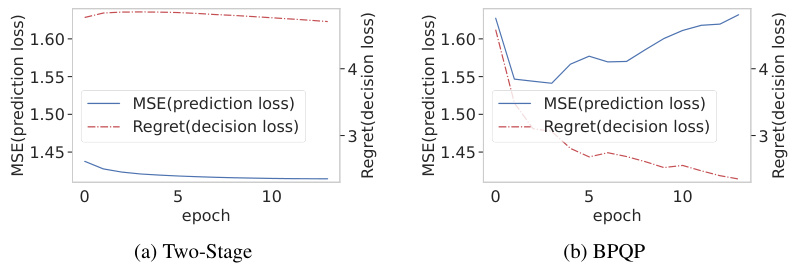

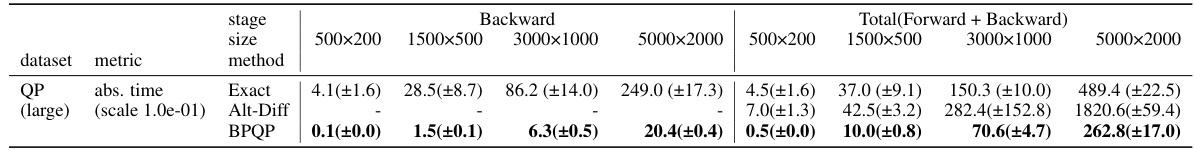

This table presents a large-scale comparison of the efficiency of different optimization methods. It shows the runtime in seconds for solving both the forward and backward passes of a convex optimization problem, with problem sizes ranging from 500x200 to 5000x2000. The methods compared are Exact, Alt-Diff, and BPQP. Lower numbers indicate better performance.

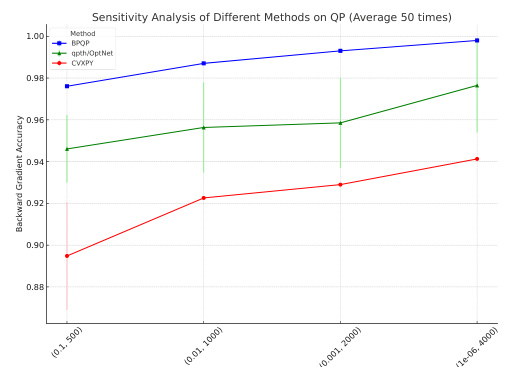

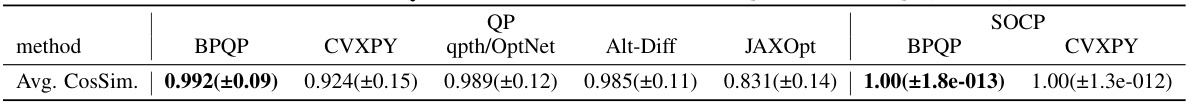

This table presents the backward pass accuracy results for various methods (BPQP, CVXPY, qpth/OptNet, Alt-Diff, JAXOpt) on both Quadratic Programming (QP) and Second-Order Cone Programming (SOCP) datasets. The accuracy is measured using the cosine similarity (CosSim) between the gradients computed by each method and a high-precision reference gradient. Lower CosSim indicates less accurate gradients.

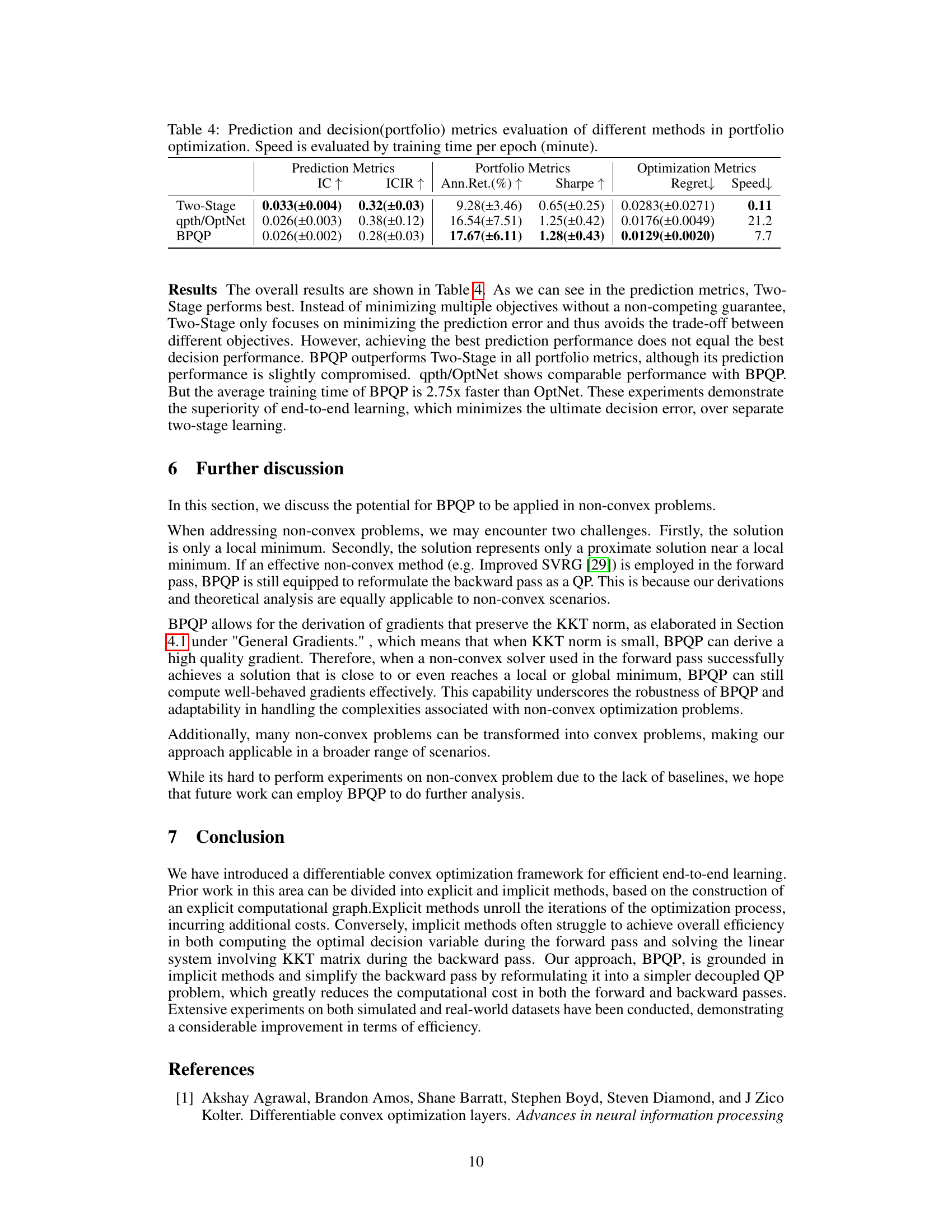

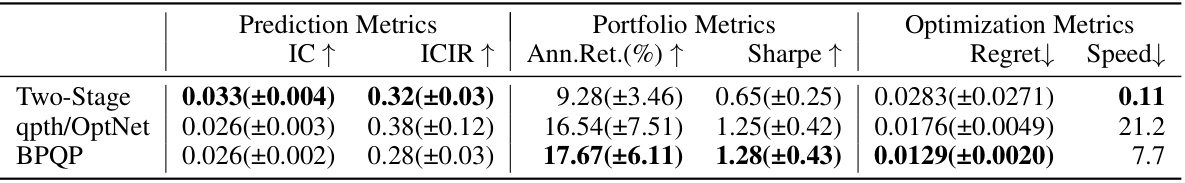

This table presents a comparison of different portfolio optimization methods. It shows the performance of three approaches: Two-Stage, qpth/OptNet, and BPQP. For each method, the table provides prediction metrics (IC and ICIR), portfolio metrics (Annualized Return and Sharpe ratio), and optimization metrics (Regret and training speed). The results highlight the trade-offs between prediction accuracy and overall portfolio performance, and the efficiency gains offered by different optimization strategies.

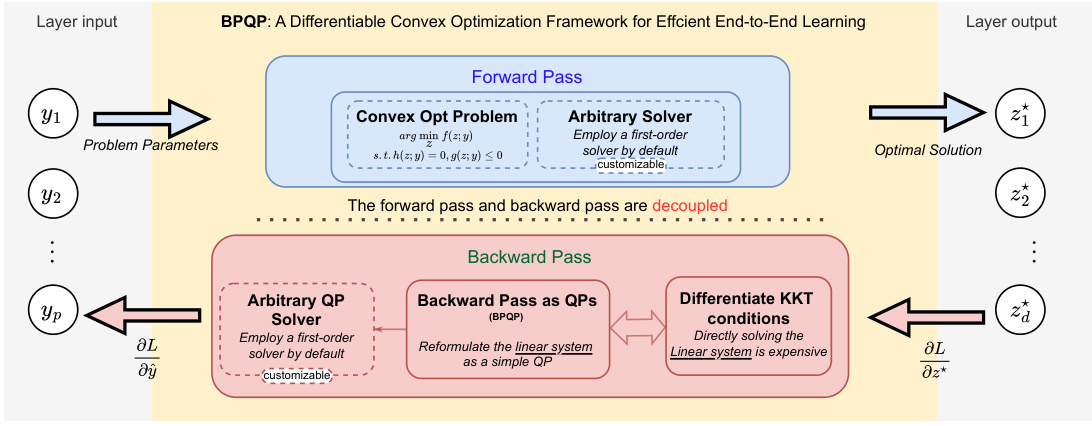

This table presents the efficiency results of the learn-to-optimize method, DC3, in terms of runtime in seconds for different problem sizes. The runtime is measured for both the forward and backward passes of the algorithm. The table shows that the runtime increases as the problem size increases, indicating that the algorithm’s computational cost scales linearly with the problem size.

This table presents the performance evaluation of the DC3 method in portfolio optimization. It includes prediction metrics (IC and ICIR), portfolio metrics (Annualized Return and Sharpe ratio), and optimization metrics (training speed). Lower values for Speed are better. Note that negative values in portfolio metrics may indicate a poor portfolio performance.

Full paper#