↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Designing proteins that bind effectively to other molecules is crucial for many applications, but creating the binding site (the “pocket”) is challenging. Current methods either rely on computationally intensive physics simulations or struggle to create high-quality pockets because they don’t fully utilize what we know about how proteins and other molecules interact. This paper introduces PocketFlow, a new method that uses “flow matching” to generate protein pockets, alongside information about how the protein and its target molecule typically interact.

PocketFlow addresses these challenges by combining flow-matching, a technique that efficiently generates diverse candidates, with information about the key interactions between proteins and their target molecules (such as hydrogen bonds). By incorporating this extra knowledge, PocketFlow produces pockets with much higher binding affinity and fewer structural flaws than previously possible. Extensive testing shows it significantly outperforms existing methods in generating high-quality binding sites for various types of molecules.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in protein engineering and drug discovery. PocketFlow offers a novel and efficient approach to protein pocket generation, surpassing existing methods in speed and accuracy. Its generalizability to diverse ligand types (small molecules, peptides, RNA) expands the potential applications and opens exciting avenues for future research in de novo protein design and biomolecular interaction studies.

Visual Insights#

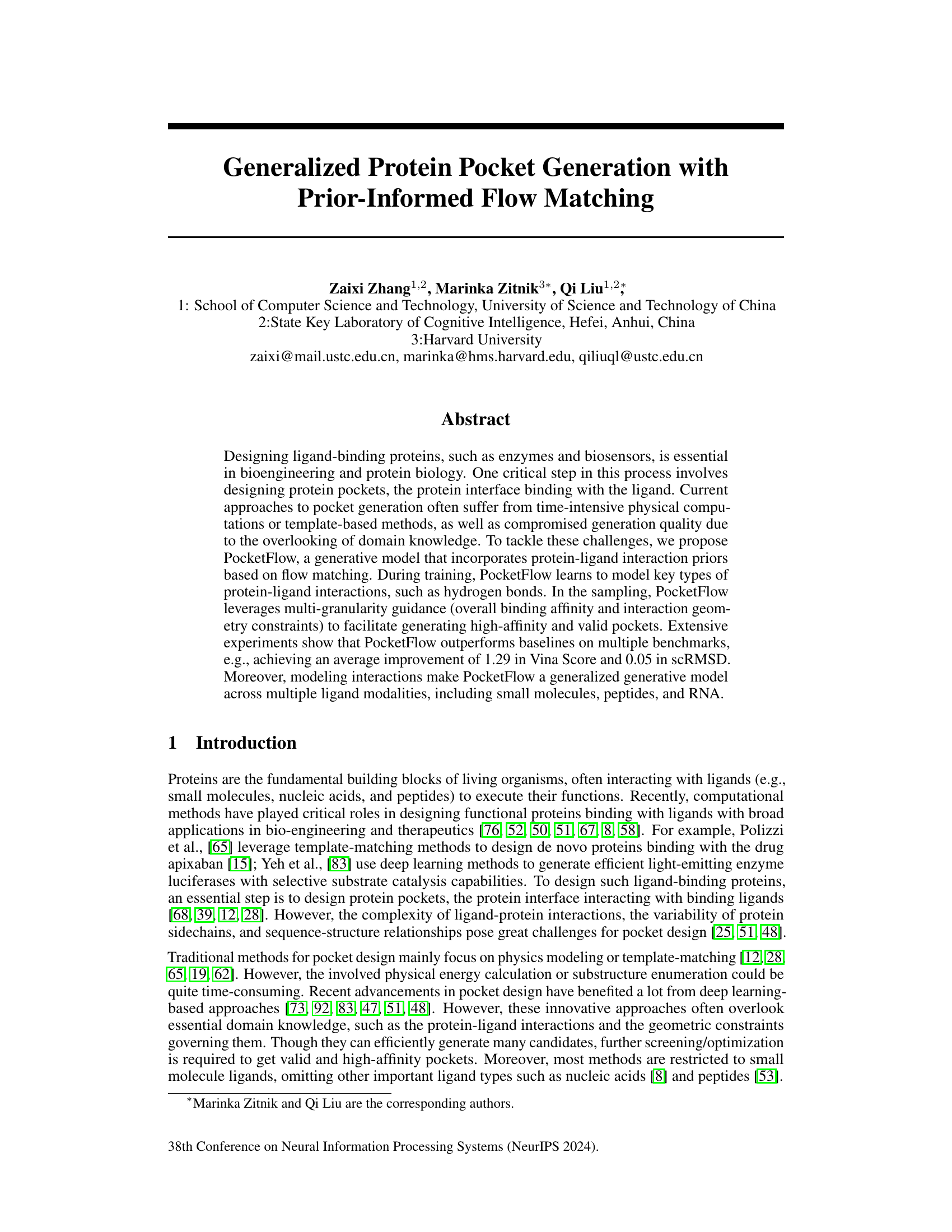

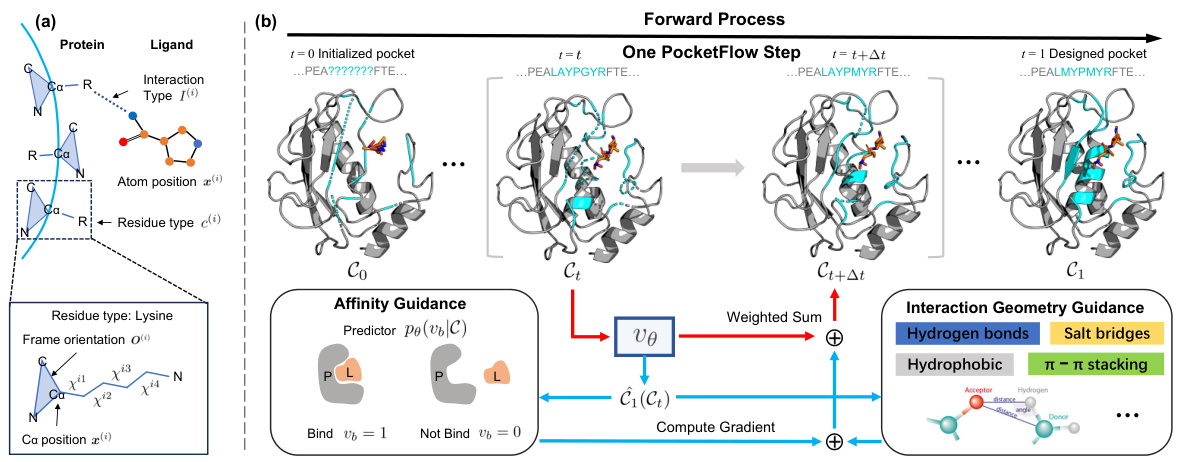

Figure 1(a) shows how the protein-ligand complex is parameterized, focusing on the protein pocket and ligand representation. This includes the residue type, frame orientation, and sidechain torsion angles for the protein residues and atom positions and types for the ligand. Figure 1(b) illustrates the PocketFlow forward process. It starts with an initialized pocket and iteratively refines it through multiple steps. Each step involves both unconditional updates (blue lines) and updates guided by the binding affinity predictor (red lines) and interaction geometry constraints (hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, hydrophobic, π-π stacking). The goal is to produce a final designed pocket (t=1) with improved binding affinity and structural validity.

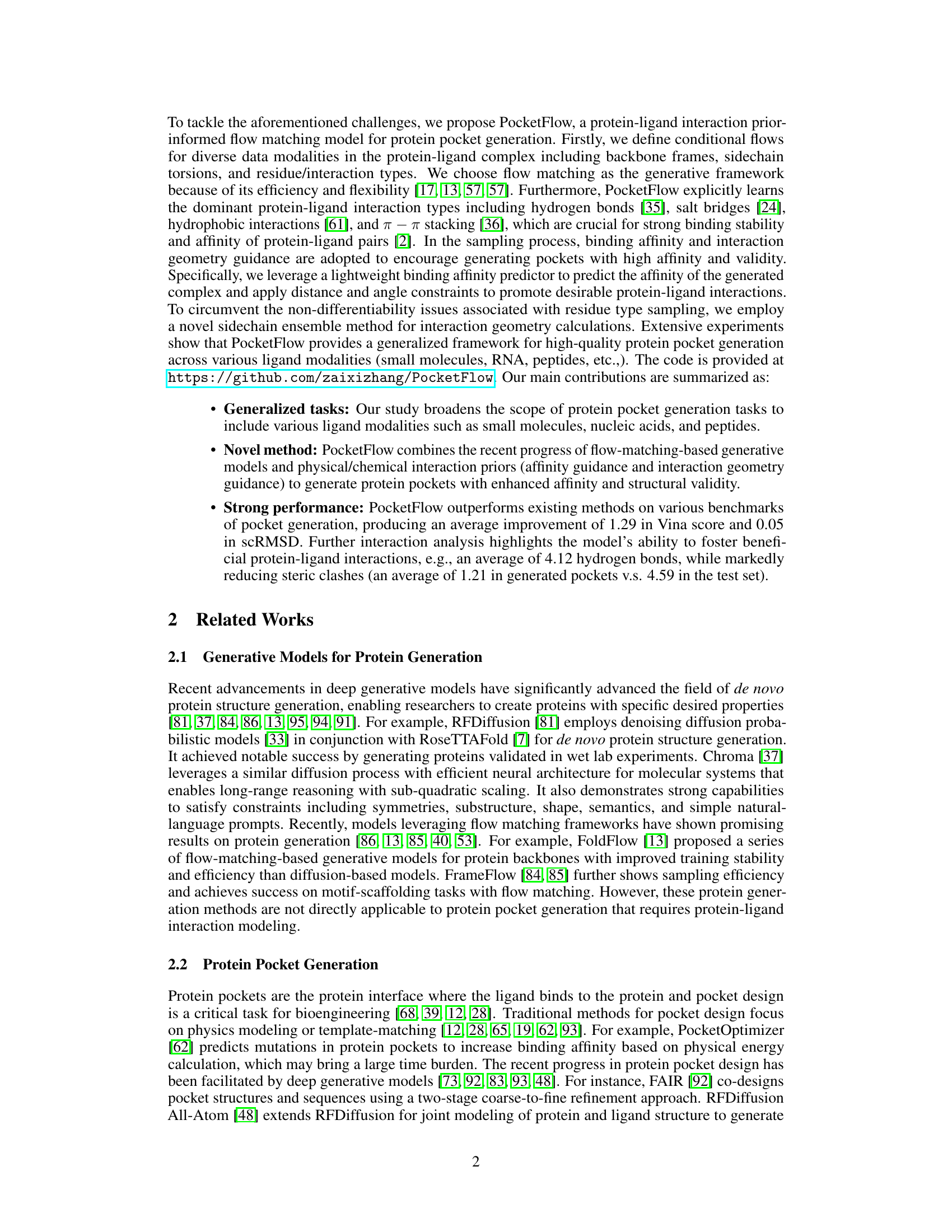

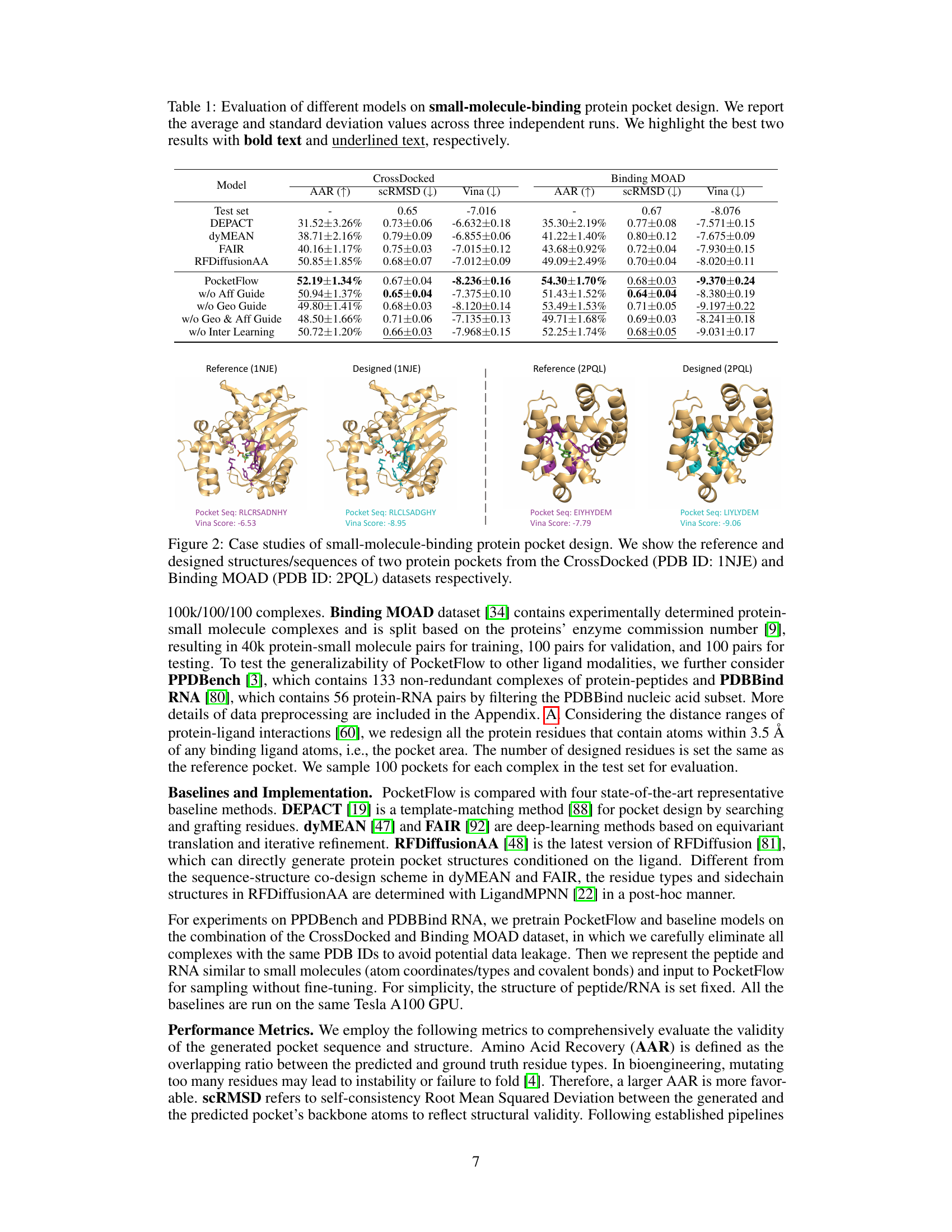

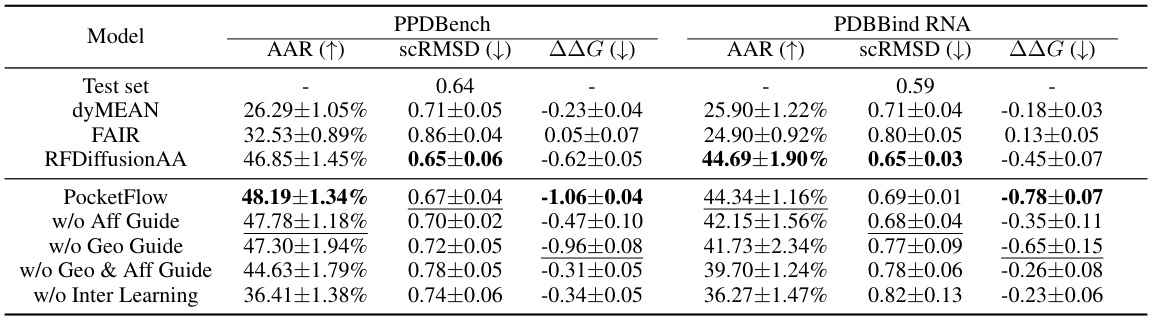

This table compares the performance of PocketFlow against other state-of-the-art methods for designing protein pockets that bind small molecules. The metrics used to evaluate the models include Amino Acid Recovery (AAR), Self-consistency Root Mean Squared Deviation (scRMSD), and Vina score. Higher AAR and lower scRMSD and Vina scores indicate better performance. The table shows that PocketFlow significantly outperforms the baselines across all three metrics.

In-depth insights#

Prior-Informed Flow#

A prior-informed flow model for protein pocket generation leverages the strengths of both generative flow models and domain expertise. Generative flow models offer efficiency and flexibility in sampling complex protein structures. However, they often lack the incorporation of crucial biological knowledge regarding protein-ligand interactions. This is where prior information comes in. By integrating prior knowledge, such as preferred interaction geometries and binding affinities, the model can generate high-quality protein pockets that are both structurally valid and functionally relevant. This approach can significantly improve the accuracy and efficiency of protein design, potentially leading to breakthroughs in drug discovery and other bioengineering applications. The model’s effectiveness depends heavily on the quality and scope of the integrated prior knowledge. The use of multi-granularity guidance, including both overall binding affinity and detailed interaction geometry, adds another layer of refinement, leading to a more robust and generalized solution.

PocketFlow Model#

The PocketFlow model presents a novel approach to protein pocket generation by integrating protein-ligand interaction priors into a flow matching framework. Its key innovation lies in leveraging multi-granularity guidance, encompassing both overall binding affinity and interaction geometry constraints, to generate high-affinity and structurally valid pockets. This approach surpasses traditional methods that are often time-consuming or compromise quality due to insufficient domain knowledge. The model’s use of conditional flows for various data modalities (backbone frames, sidechains, interaction types) allows it to handle diverse ligand types, making it a generalized generative model. PocketFlow’s incorporation of physical and chemical interaction priors, including hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, enhances its accuracy and generalizability. While the model shows promising results, future work could explore refinements such as incorporating sequential flow matching techniques or expanding its training data to include a wider range of ligand modalities. The model’s efficiency and flexibility make it a significant advancement in protein engineering.

Multi-Ligand Design#

Multi-ligand design in protein engineering presents a significant challenge and opportunity. Success hinges on developing methods capable of predicting and optimizing protein-ligand interactions across diverse ligand types, such as small molecules, peptides, and nucleic acids. This necessitates moving beyond single-ligand approaches, which often fail to capture the complexity of biological systems. A comprehensive solution would require integrating advanced computational modeling techniques with experimental validation to address the variability in ligand structures and their interactions with proteins. Machine learning holds immense promise in accelerating this process by identifying common patterns and predictive features across multiple ligand modalities. However, challenges remain, including the need for large, high-quality datasets representing diverse protein-ligand interactions and the development of robust evaluation metrics that assess binding affinity, specificity, and overall biological function. Furthermore, incorporating domain knowledge about protein-ligand interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions) is essential for guiding model development and ensuring the generation of biologically realistic and functional designs. The ultimate goal is to create a powerful design platform facilitating the rapid and efficient creation of proteins with precisely tailored multi-ligand binding capabilities, advancing applications in drug discovery, diagnostics, and synthetic biology.

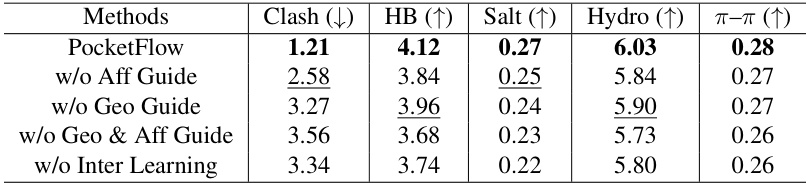

Ablation Studies#

Ablation studies systematically remove or deactivate components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a protein pocket generation model, this might involve removing different aspects such as the affinity predictor, interaction geometry guidance, or specific interaction types. Results from such studies would reveal the importance of each component, highlighting which features are crucial for the model’s performance and which are less critical. For instance, a significant drop in accuracy after removing the affinity predictor would indicate its importance in generating high-affinity pockets. Conversely, a minimal performance decrease when removing a particular interaction type could indicate its lesser importance. These insights are valuable for optimizing the model, identifying redundant components, and understanding the underlying principles driving successful protein pocket design. Well-designed ablation studies offer a granular level of understanding, facilitating targeted improvements and allowing researchers to focus on critical model elements while removing unnecessary complexity.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore improving PocketFlow’s efficiency by optimizing the flow matching framework or investigating more efficient neural architectures. Expanding the range of ligand types beyond small molecules, peptides, and RNA to include larger molecules or macromolecular complexes is also crucial. Additionally, incorporating more sophisticated physical and chemical priors could further improve pocket generation quality, perhaps through incorporating explicit solvent effects or more accurate modeling of protein flexibility. A key area for future work would be developing robust validation strategies for the generated pockets, including efficient computational methods and experimental techniques for assessing binding affinity and specificity. Finally, exploring applications of PocketFlow in protein engineering and drug design presents exciting opportunities, including generating novel enzymes with enhanced catalytic activity or designing highly specific biosensors.

More visual insights#

More on figures

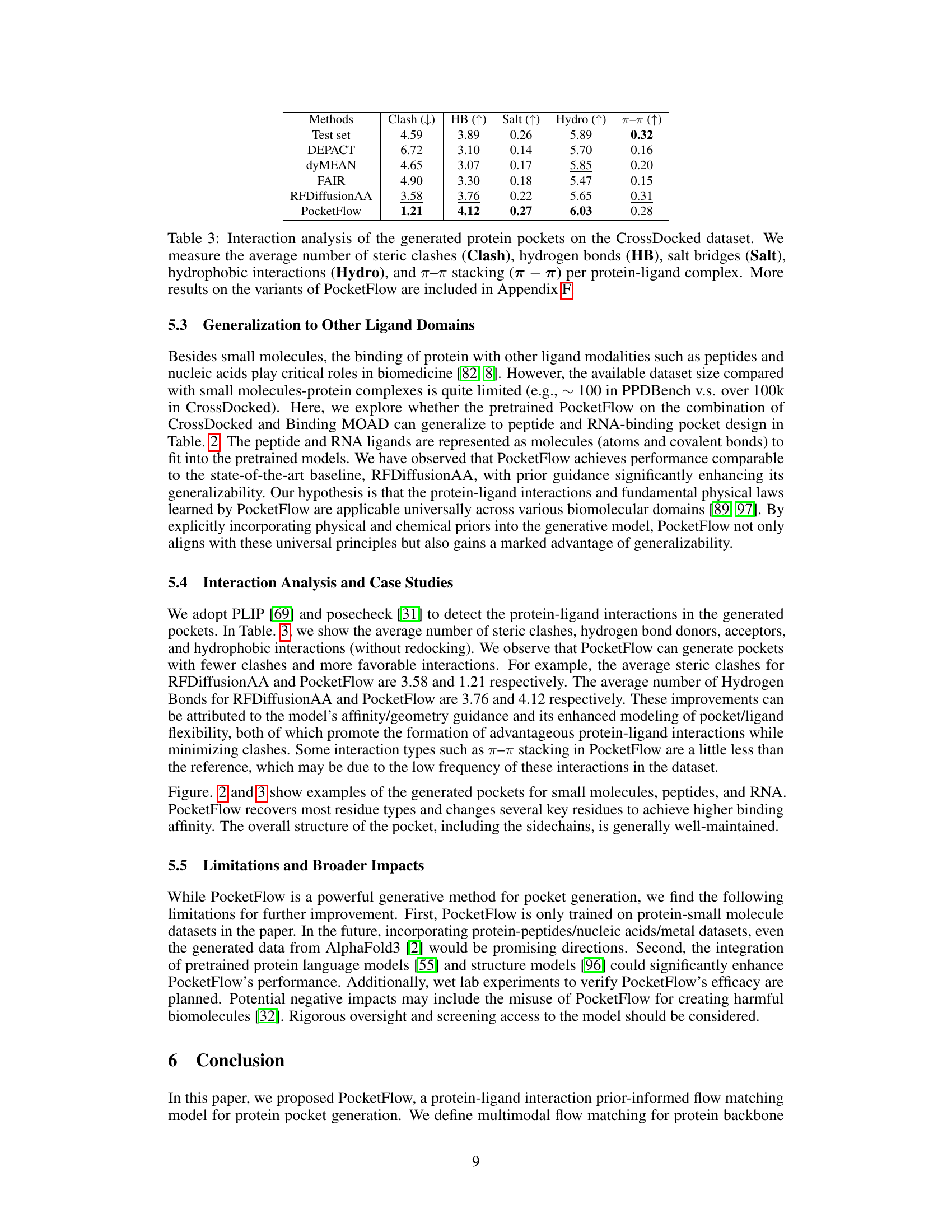

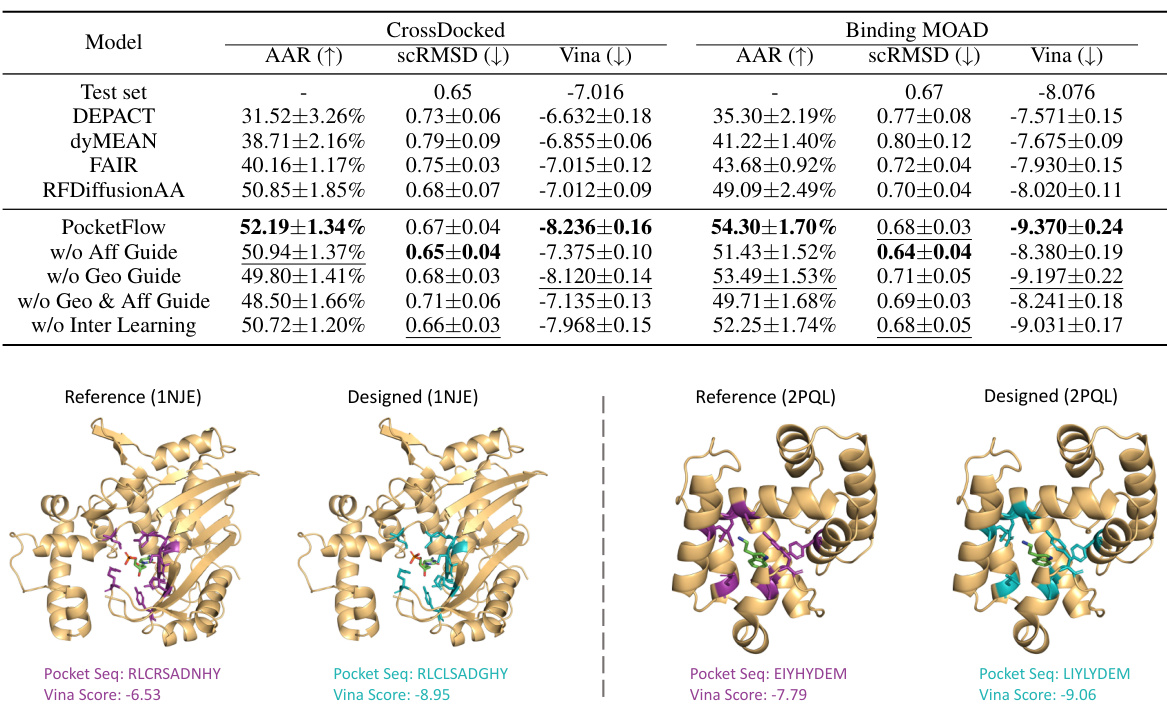

This figure showcases two examples of small-molecule binding protein pocket designs generated by the model. For each example, it shows both the original (‘reference’) protein structure and the structure generated by PocketFlow. Key information, such as the protein pocket sequences and Vina scores (which reflects binding affinity) are provided for both the original and the designed protein pockets, highlighting the model’s ability to improve the binding affinity.

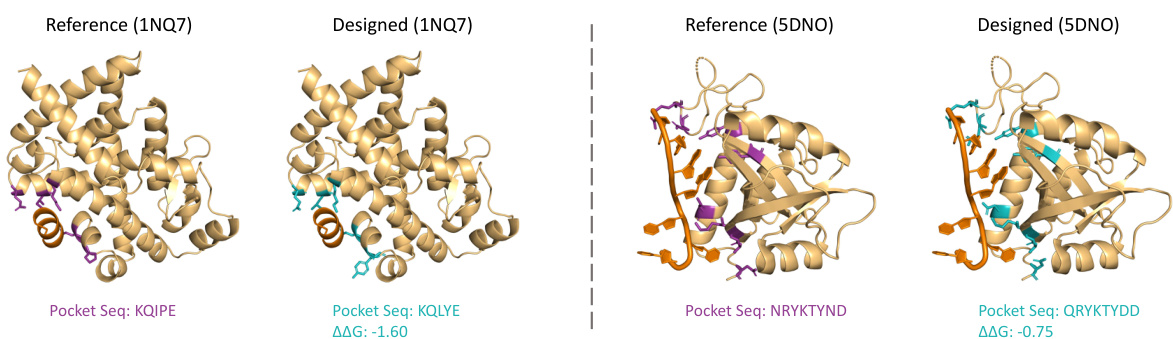

This figure showcases two case studies illustrating PocketFlow’s ability to design protein pockets for peptide and RNA ligands. It presents the reference and PocketFlow-designed structures side-by-side for two protein-ligand complexes from the PPDBench and PDBBind RNA datasets. The designs are evaluated based on amino acid recovery (AAR) and changes in binding affinity (AAG). The ligand molecules are shown in orange, highlighting the binding location within the protein pocket.

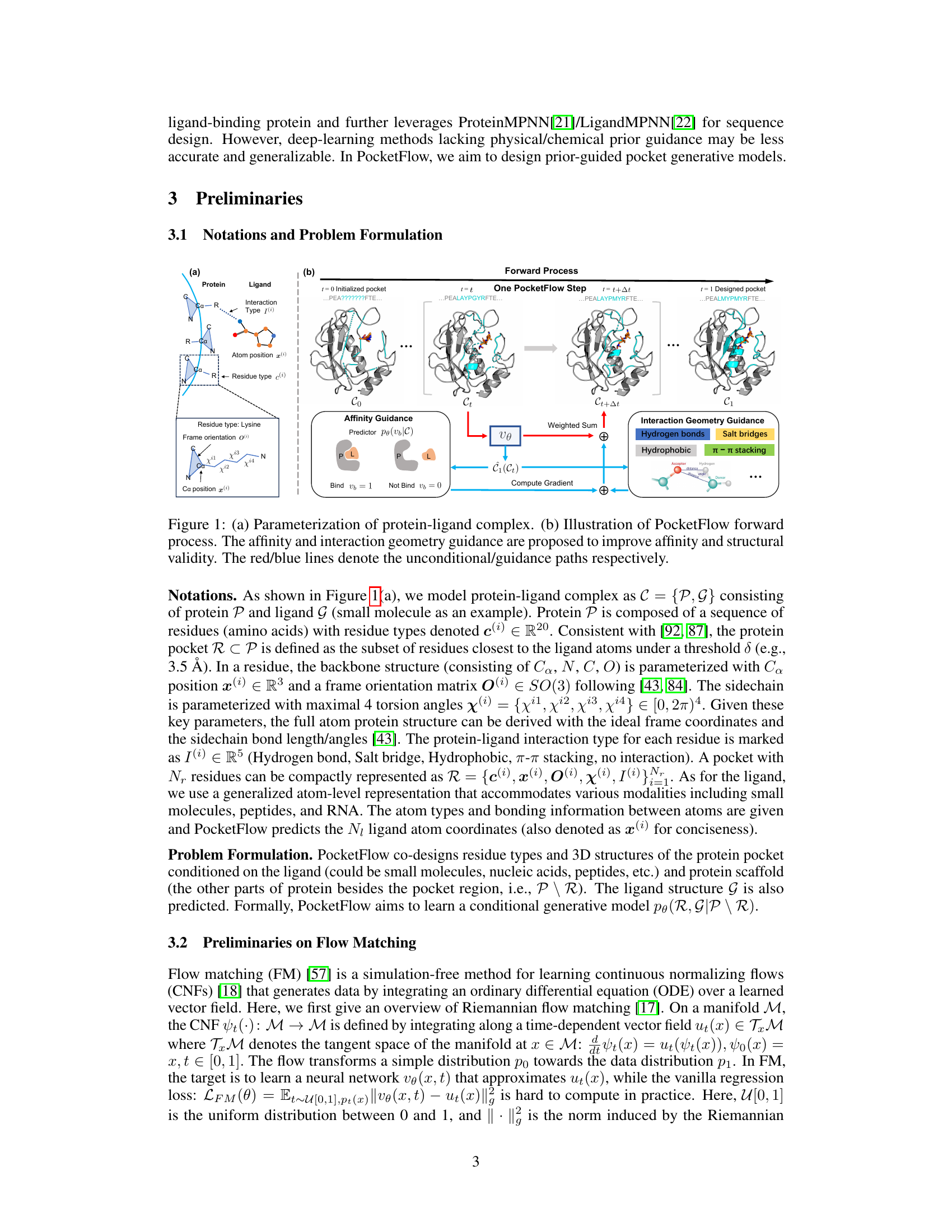

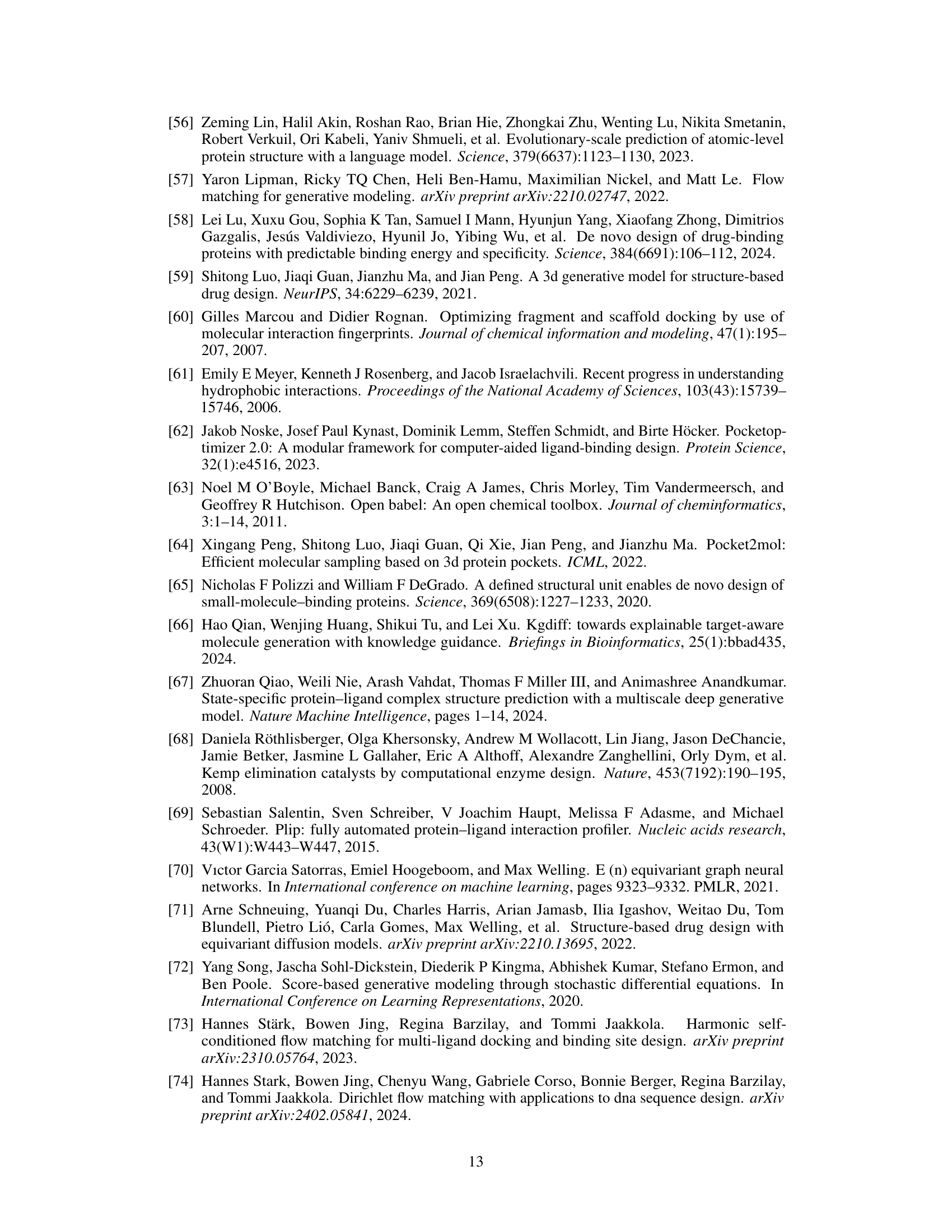

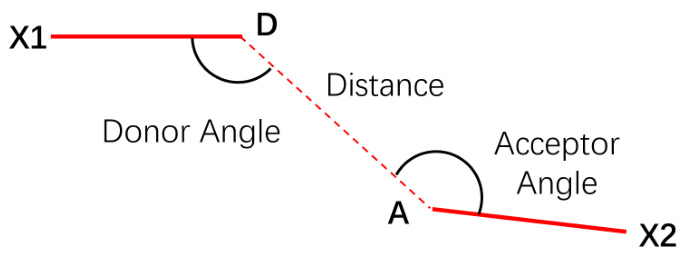

This figure illustrates the geometric constraints involved in forming a hydrogen bond. It shows the donor (D) and acceptor (A) atoms, the distance between them, and the angles formed by the donor and acceptor atoms with their neighboring atoms (X1 and X2). These constraints are important for ensuring a stable hydrogen bond.

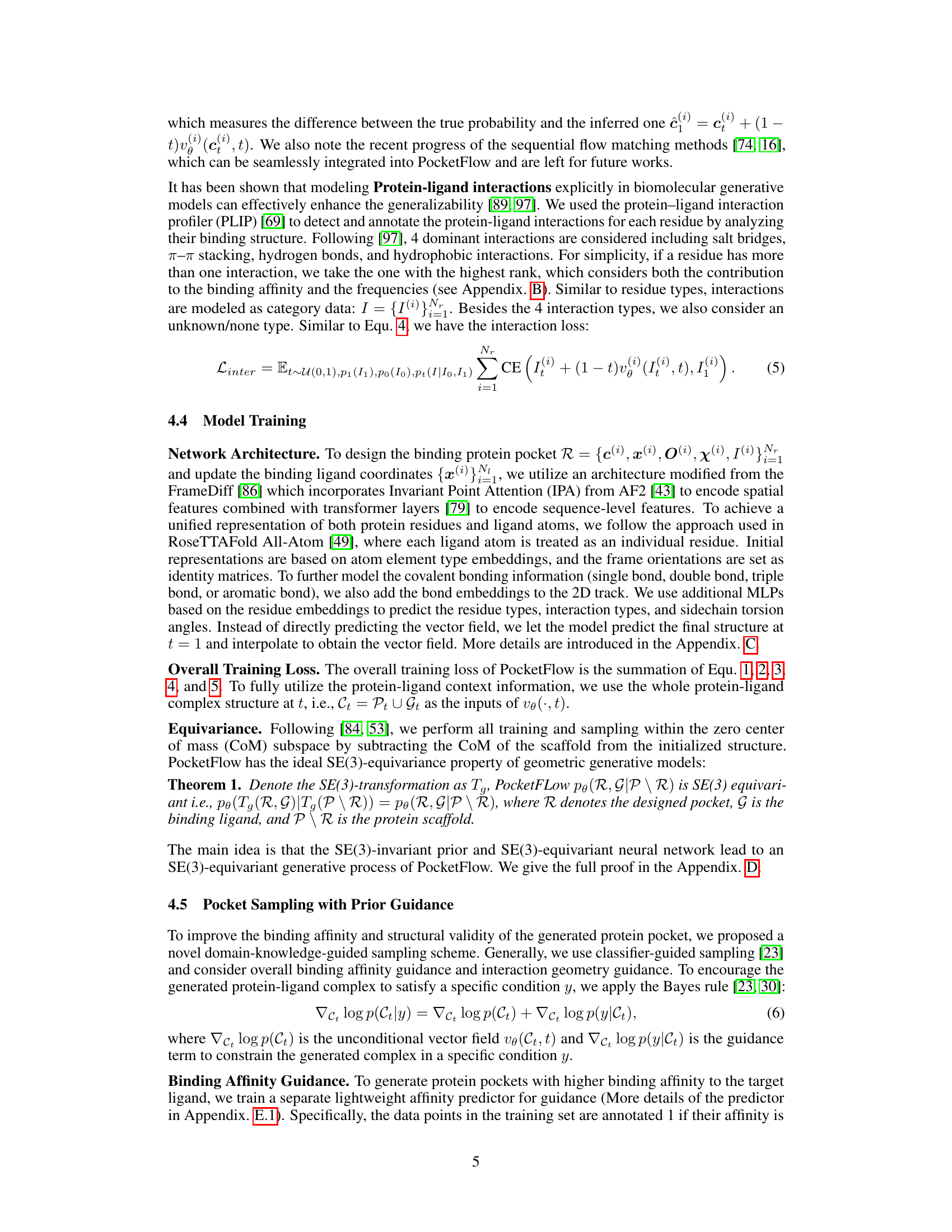

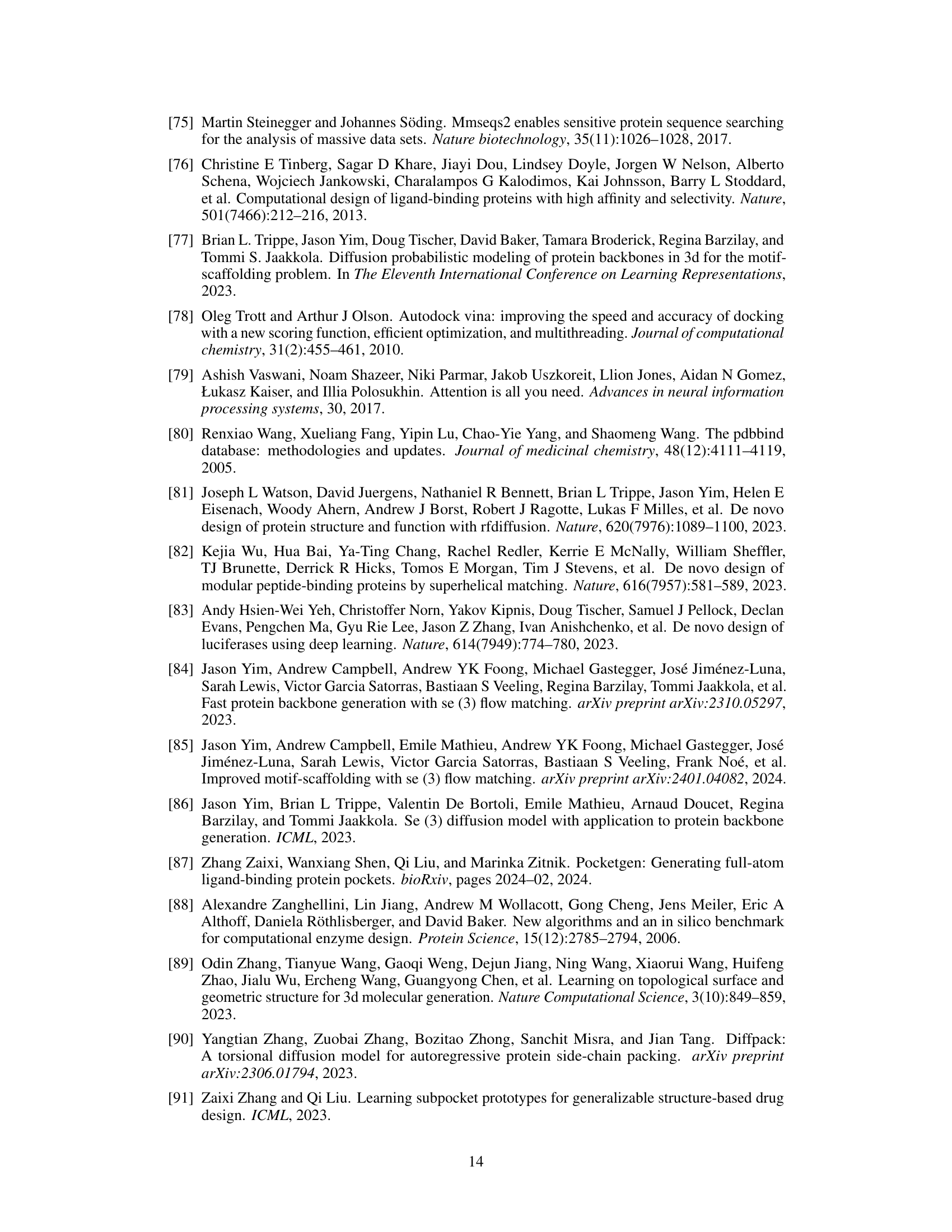

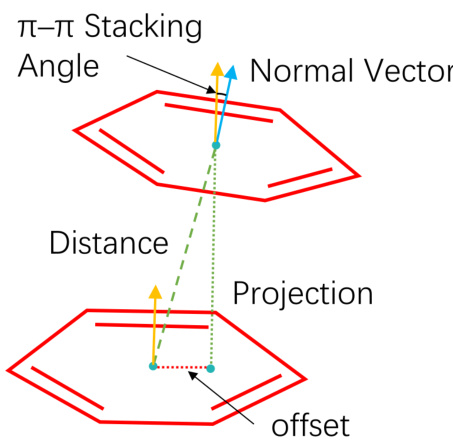

This figure illustrates the geometric constraints for π-π stacking interactions. Two aromatic rings are shown, with their centers indicated by cyan dots. The distance between these centers, the angle between the normal vectors of their planes (represented by yellow and light blue arrows), and the offset of the projection of one ring’s center onto the plane of the other ring are all shown and defined as factors to determining if a π-π stacking interaction occurs.

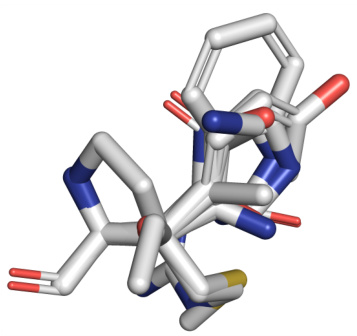

This figure shows a superposition of 20 different residue-type sidechains. The method uses predicted residue type probabilities to estimate sidechain conformations which are then used in calculating geometry guidance for the PocketFlow model. This approach is designed to address the non-differentiability issue associated with directly sampling from the residue type distribution.

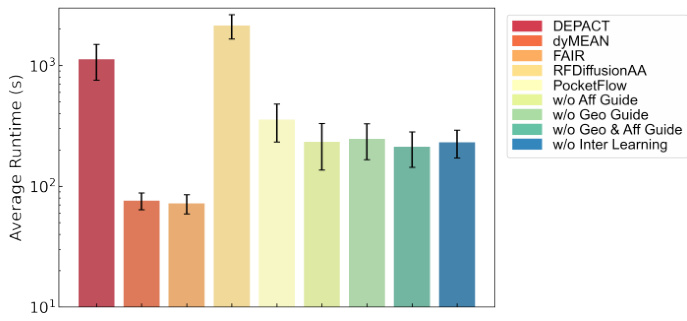

This figure compares the average time taken by different models to generate 100 protein pockets. The models compared include DEPACT, dyMEAN, FAIR, RFDiffusionAA, and several variants of the PocketFlow model (with and without different guidance components). The error bars represent the standard deviation across multiple runs, indicating the variability in generation time for each model.

This figure shows the impact of varying the affinity guidance strength (γ) on three key pocket metrics: Vina score (a measure of binding affinity), amino acid recovery (AAR; a measure of sequence similarity to the ground truth), and self-consistency root mean squared deviation (scRMSD; a measure of structural similarity to the ground truth). The x-axis represents the strength of the affinity guidance (γ), and the y-axis represents the value of the respective metric. The figure demonstrates that an optimal γ value exists that balances the benefits of guidance with the risk of over-regularization, resulting in higher affinity and better structural accuracy.

More on tables

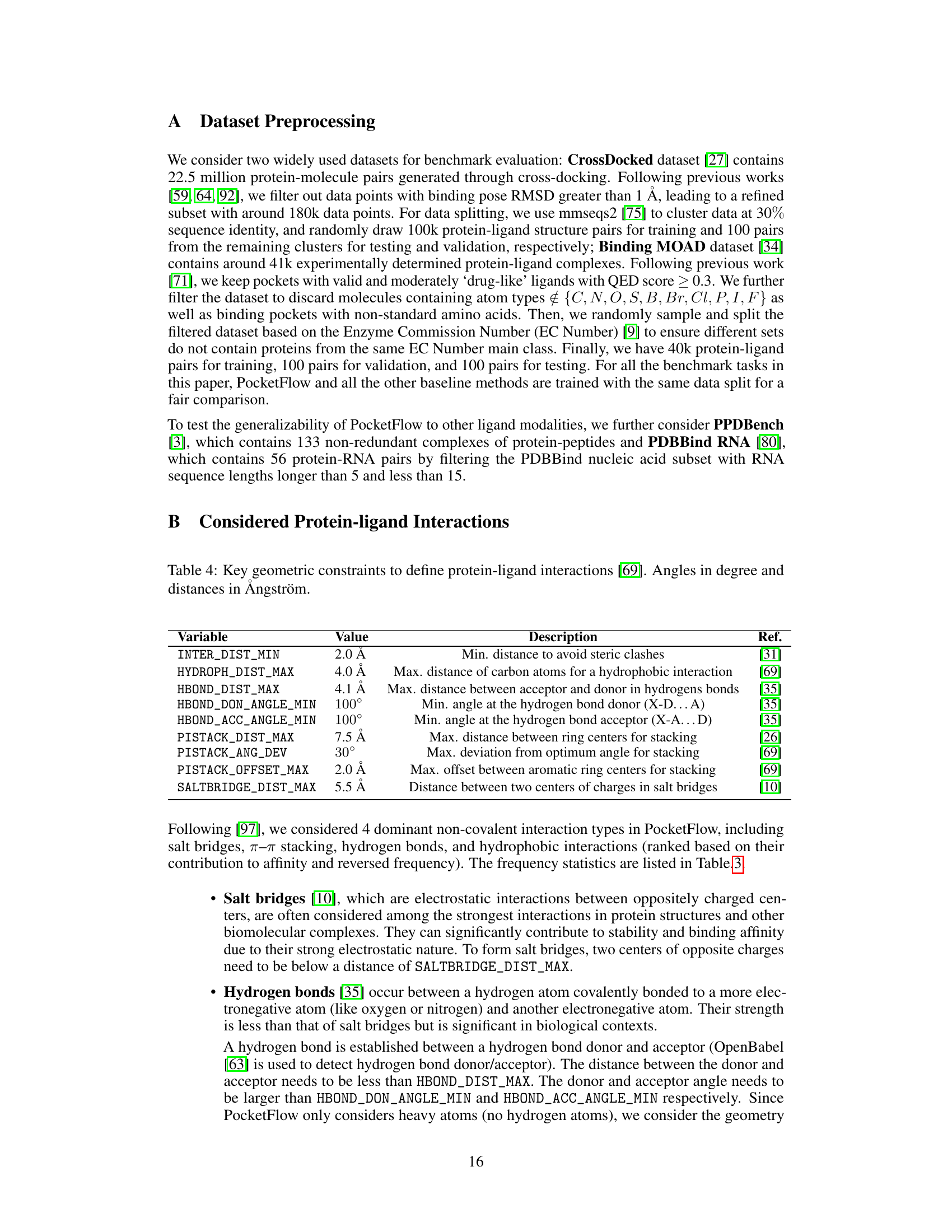

This table compares the performance of PocketFlow against several baseline models (DEPACT, dyMEAN, FAIR, and RFDiffusionAA) on two benchmark datasets for small molecule protein pocket generation (CrossDocked and Binding MOAD). The evaluation metrics include Amino Acid Recovery (AAR), sidechain RMSD (scRMSD), and Vina score. Higher AAR and lower scRMSD and Vina scores indicate better performance.

This table presents a comparison of various methods for designing small-molecule-binding protein pockets. The performance of different models (DEPACT, dyMEAN, FAIR, RFDiffusionAA, and PocketFlow, along with several ablation studies of PocketFlow) is evaluated using three metrics: Amino Acid Recovery (AAR), self-consistency Root Mean Squared Deviation (scRMSD), and Vina score. Higher AAR indicates better sequence similarity, lower scRMSD indicates better structural similarity to the reference, and lower Vina score indicates higher binding affinity. The table shows average values and standard deviations across three independent runs for each model and metric. The best performing models for each metric are highlighted.

This table compares the performance of PocketFlow against other state-of-the-art methods for designing small molecule-binding protein pockets. The metrics used are Amino Acid Recovery (AAR), sidechain Root Mean Square Deviation (scRMSD), and Vina score. Higher AAR and lower scRMSD and Vina scores indicate better pocket designs. The table shows that PocketFlow outperforms the baselines across all metrics.

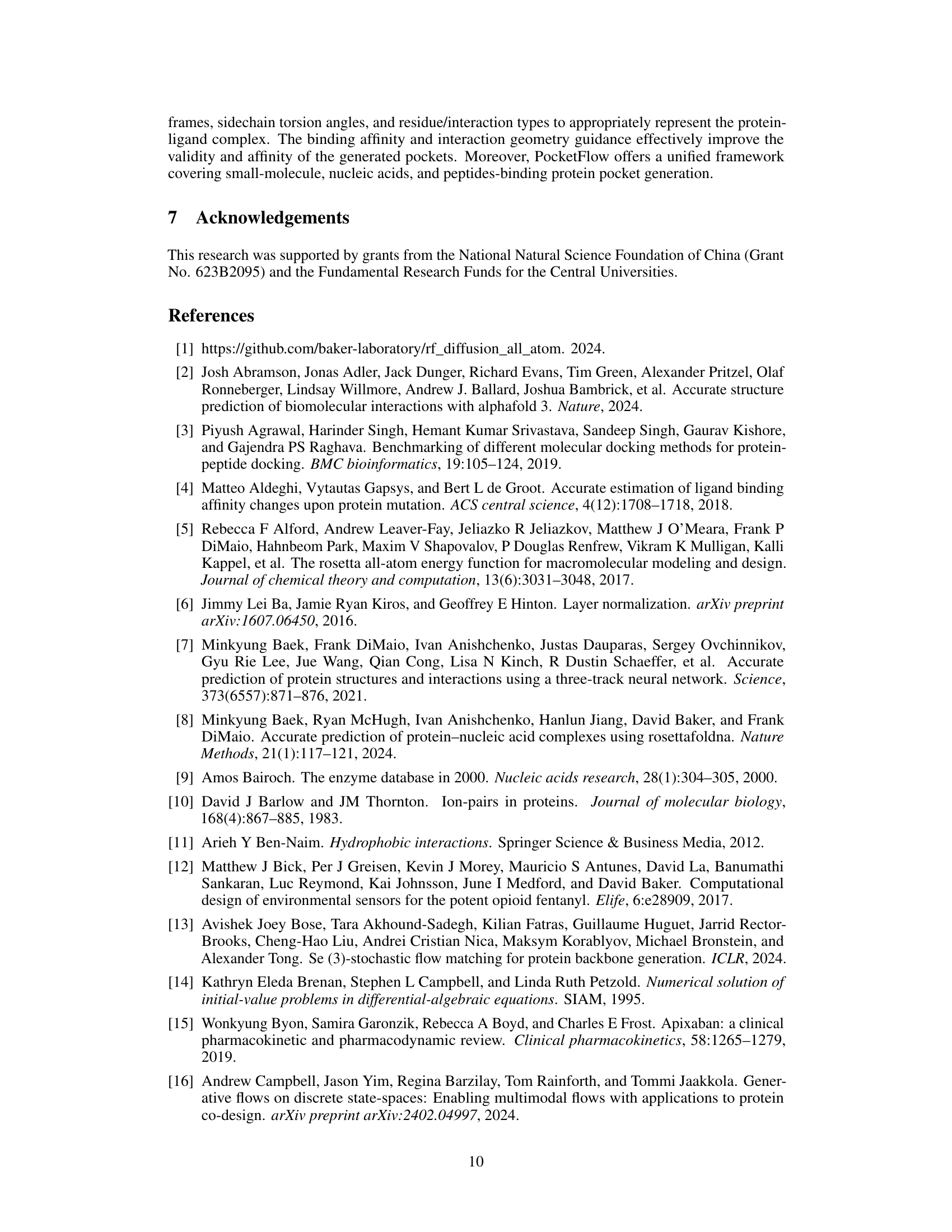

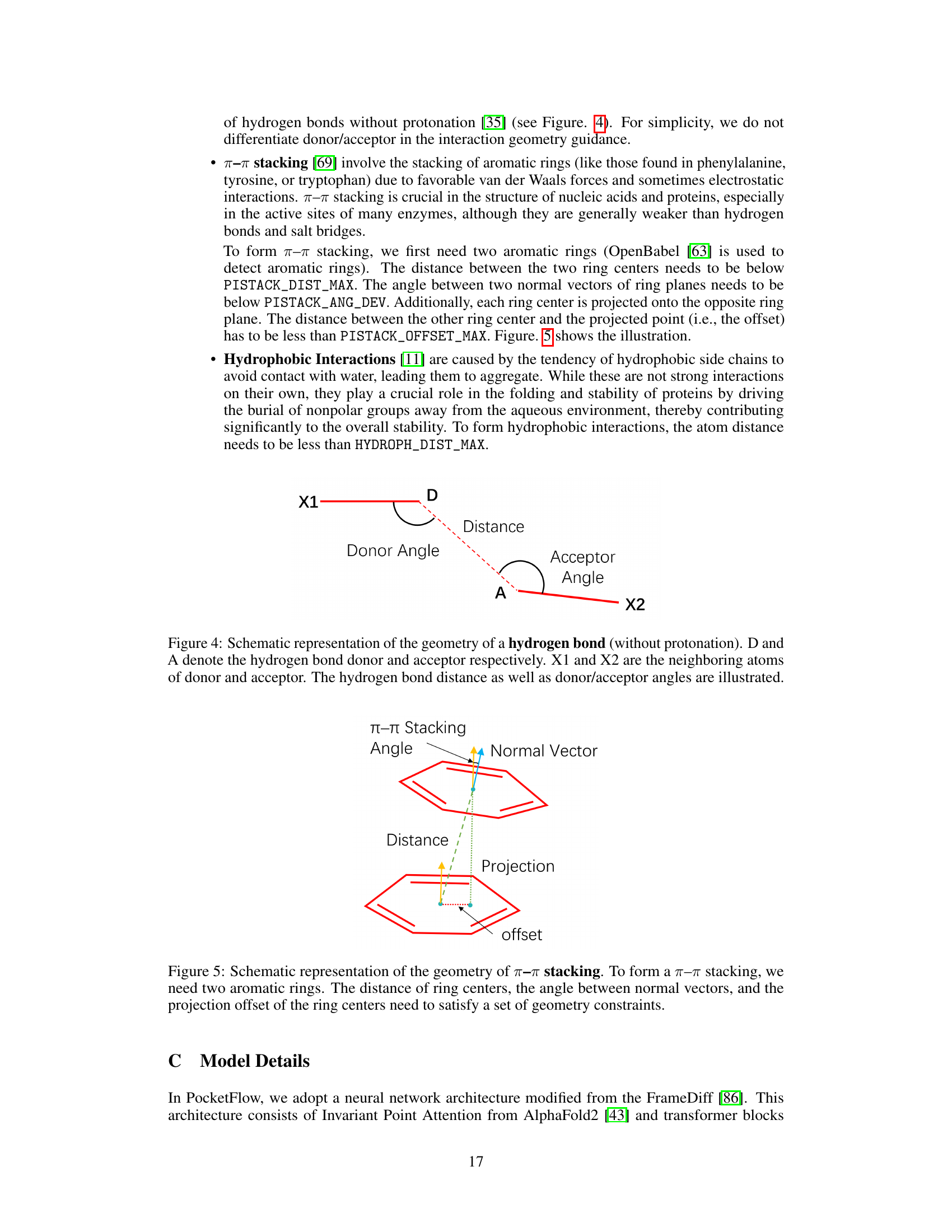

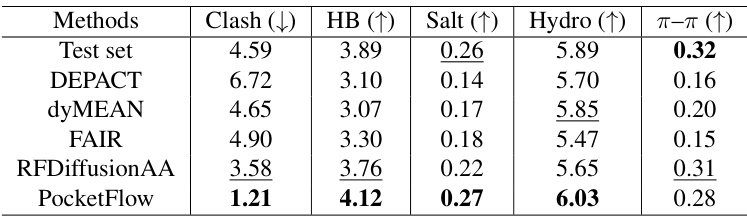

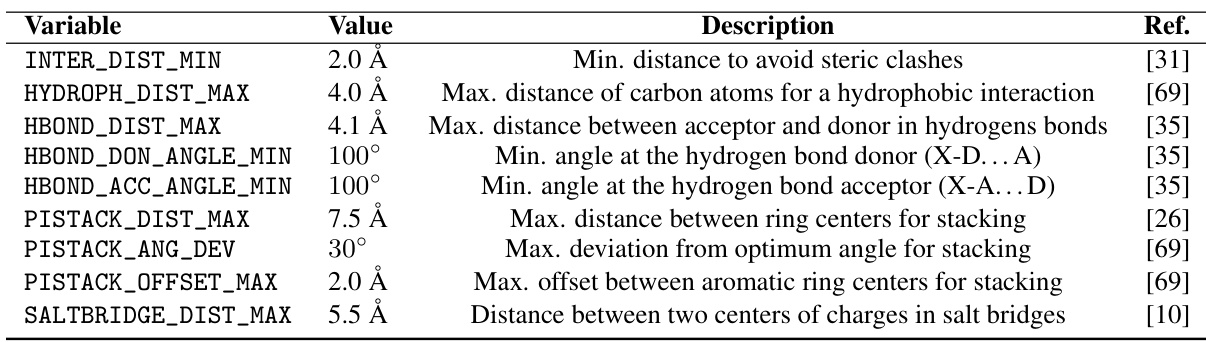

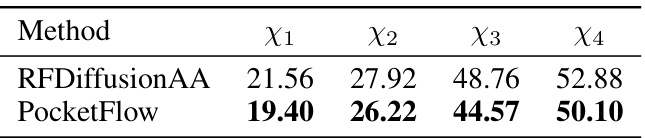

This table presents the results of ablation studies on the interaction analysis of the PocketFlow model. It shows the average number of steric clashes, hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, hydrophobic interactions, and π-π stacking per protein-ligand complex for different versions of the model. Each version removes a specific component: Affinity Guidance, Geometry Guidance, both guidance, or inter-learning. The results demonstrate the contribution of each component to the overall performance of the model. The best-performing versions for each metric are highlighted.

Full paper#