↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Existing vision-language models (VLMs) struggle to handle complex real-world scenarios and align with diverse human attention patterns. This limits their practical applications and user experience. The integration of gaze information, collected via AR/VR devices, is proposed as a solution to enhance VLM performance and interpretability.

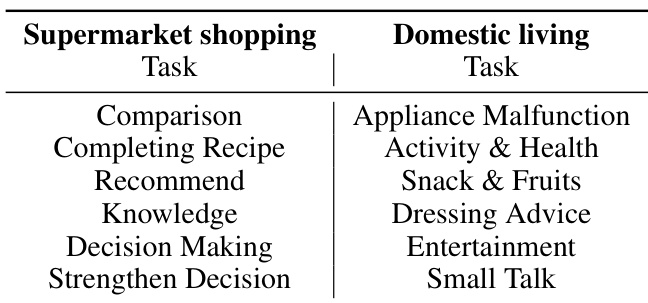

The paper introduces Voila-A, a novel approach that uses gaze data to align VLM attention. It features a new dataset (VOILA-COCO, created with GPT-4, and VOILA-GAZE, collected using gaze-tracking devices) and innovative “Voila Perceiver” modules to integrate gaze information into pre-trained VLMs. Experimental results on hold-out and real-life test sets show significant improvements over baselines, demonstrating the effectiveness of Voila-A in enhancing VLM performance and creating more user-centric interactions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on vision-language models and human-computer interaction. It addresses the critical need for aligning model attention with human gaze, improving user experience and interpretability. By introducing a novel approach and dataset, it opens avenues for more intuitive, user-centric AI applications and fosters engaging human-AI interactions across diverse fields. The innovative methods, evaluation metrics, and dataset offer valuable contributions for future research and development in the field.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows example scenarios using AR and VR devices. It highlights that real-world scenes are often complex, containing multiple objects. Users typically focus their attention on a single object of interest at a time. The figure suggests that gaze tracking is a more natural and intuitive way for users to interact with such devices compared to other input methods.

This table presents the statistics of the two datasets used in the paper: Voila-COCO and Voila-Gaze. Voila-COCO is a large-scale dataset automatically annotated using GPT-4, while Voila-Gaze is a smaller, real-world dataset collected using gaze-tracking devices. The table shows the number of images and questions in each dataset split (training, validation, test) and the survival rate (SR) after filtering.

In-depth insights#

Gaze-VLM Alignment#

Aligning Vision-Language Models (VLMs) with human gaze presents a crucial challenge and opportunity. Effective gaze-VLM alignment hinges on bridging the gap between the model’s internal attention mechanisms and the user’s visual focus. This necessitates innovative methods for representing gaze data, such as heatmaps derived from eye-tracking or even mouse traces as proxies. The integration of gaze data must be seamlessly incorporated into the VLM’s architecture, potentially through attention mechanisms or specialized modules that modulate the model’s attention based on gaze information, without significant architectural modifications or catastrophic forgetting of pre-trained knowledge. Furthermore, robust evaluation metrics beyond traditional VLM benchmarks are critical, incorporating aspects of user experience, intentionality, and model interpretability. Ultimately, successful gaze-VLM alignment will pave the way for more natural and intuitive human-computer interaction, especially in applications such as AR/VR where gaze is a primary interaction modality.

Trace Data as Proxy#

Employing trace data, such as mouse movements, as a proxy for gaze data presents a cost-effective and scalable alternative to directly collecting gaze data, which can be expensive and time-consuming. This approach is particularly valuable in scenarios involving complex scenes or extended interaction durations where obtaining precise gaze data is challenging. While trace data might not perfectly mirror the nuances of gaze patterns, studies show reasonable correlations, making it a suitable substitute, especially when combined with techniques to enhance its similarity to gaze data (e.g., downsampling and heatmap transformation). However, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of using trace data as a proxy. Potential discrepancies between trace and gaze may introduce noise or inaccuracies in models trained on such data. Therefore, careful consideration of these limitations and robust evaluation strategies are paramount to ensure the reliability of findings when using trace data as a proxy for gaze in vision-language model alignment tasks.

Voila-A Architecture#

The Voila-A architecture appears to be designed for efficient integration of gaze information into existing Vision-Language Models (VLMs), likely leveraging a pre-trained VLM as a foundation. A key innovation seems to be the Voila Perceiver module, which integrates gaze data seamlessly without extensive modification of the pre-trained network. This module likely employs a multi-stage processing pipeline. The first stage could involve converting gaze data into a meaningful representation, such as a heatmap, followed by encoding this information into key embeddings. A subsequent stage probably integrates these gaze embeddings with image features through a mechanism like gated cross-attention. The final stage would then feed the combined representation into subsequent layers of the pre-trained VLM, allowing the model to leverage both visual and gaze information for enhanced understanding. The use of a heatmap representation for gaze is notable, as it provides a spatially rich representation that can be easily integrated into existing convolutional or attention-based architectures. The architecture appears to prioritize minimal modification of the pre-trained VLM weights, thereby preserving pre-trained knowledge while enhancing performance. The framework is probably designed for scalability, making it suitable for integration with large-scale VLMs and diverse real-world applications. By aligning the model’s attention with human gaze patterns, Voila-A aims to create more intuitive, user-centric interactions.

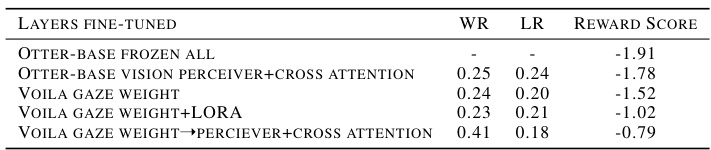

Ablation Study Results#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to understand their individual contributions. In this context, an ablation study on a vision-language model (VLM) might involve removing or altering different modules to assess the impact on performance metrics such as accuracy or user satisfaction. Removing a gaze integration module, for example, would reveal its effectiveness in aligning the model’s attention with human gaze patterns. Analyzing results across various ablations provides insights into the relative importance of different architectural choices, training techniques, or data augmentation strategies. For instance, comparing performance with and without gaze data reveals whether the additional data significantly improves the model’s understanding of user intent. Furthermore, ablation studies can help identify potential bottlenecks or areas where the model struggles. A drop in performance after removing a specific component highlights its importance and suggests areas that need more attention during model development or training. It provides a systematic way of identifying areas for optimization, guiding future model design and improving the overall user experience and the VLM’s capabilities. These insights would be crucial for enhancing the VLM’s effectiveness and interpreting the results of the main experiments more comprehensively. By understanding which parts of the model are crucial, researchers can refine and improve future iterations of the VLM.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Improving the efficiency of the inference process is crucial for real-time applications. This could involve optimizing the model architecture or employing more efficient training techniques. Expanding the model to incorporate other modalities, such as audio or haptic feedback, would enhance user interaction and potentially broaden applicability. Addressing the occasional hallucinations observed in the model’s responses is another important area. This may require increased training data or more sophisticated methods to handle complex visual scenarios. Investigating the effects of different types of user input, besides gaze, could enhance the model’s adaptability and usability. For example, comparing performance using mouse traces versus direct touch input. Finally, applying the model to a wider range of real-world applications should be explored, such as educational contexts, assistive technology, and interactive gaming, to better understand the model’s limitations and strengths in different settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

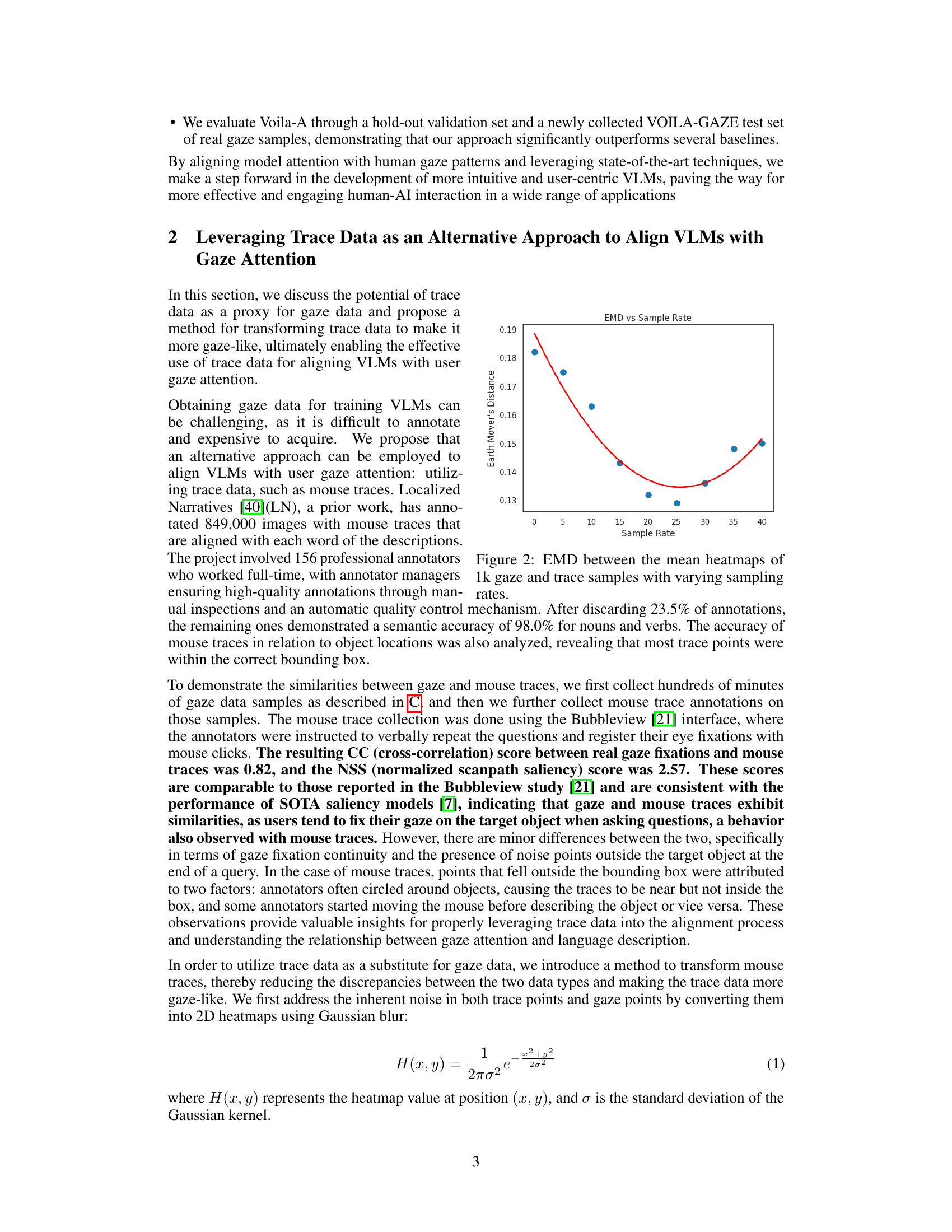

This figure shows the Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD) between the average heatmaps of 1,000 gaze and trace samples at different sampling rates. The EMD measures the difference between two probability distributions, in this case representing the similarity between gaze and mouse trace data. The x-axis represents the sampling rate, and the y-axis represents the EMD. A lower EMD indicates greater similarity. The graph shows that the EMD has a local minimum around a sampling rate of 25, suggesting that this sampling rate effectively transforms the trace data to be more similar to gaze data. This finding supports using mouse trace data as a proxy for gaze data in training vision-language models.

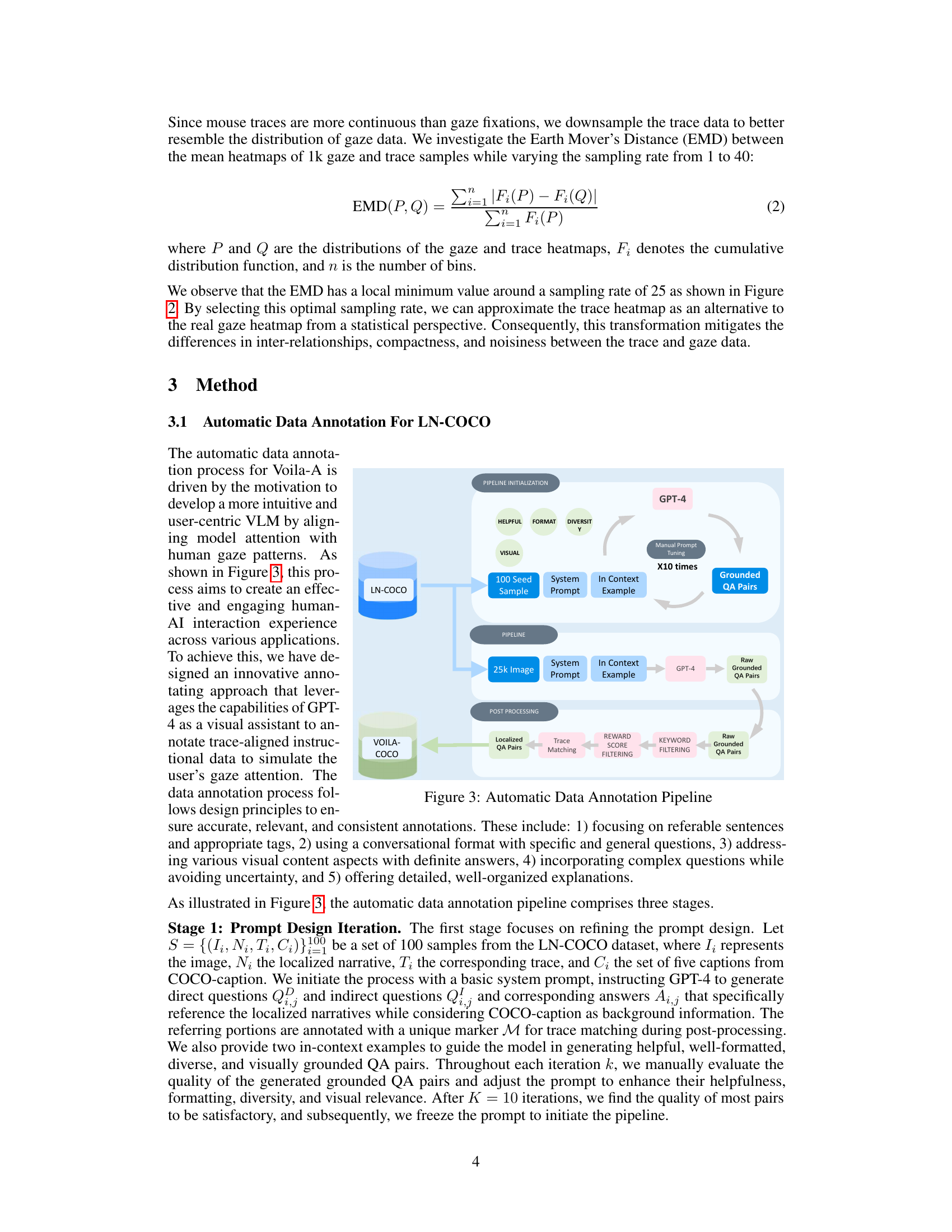

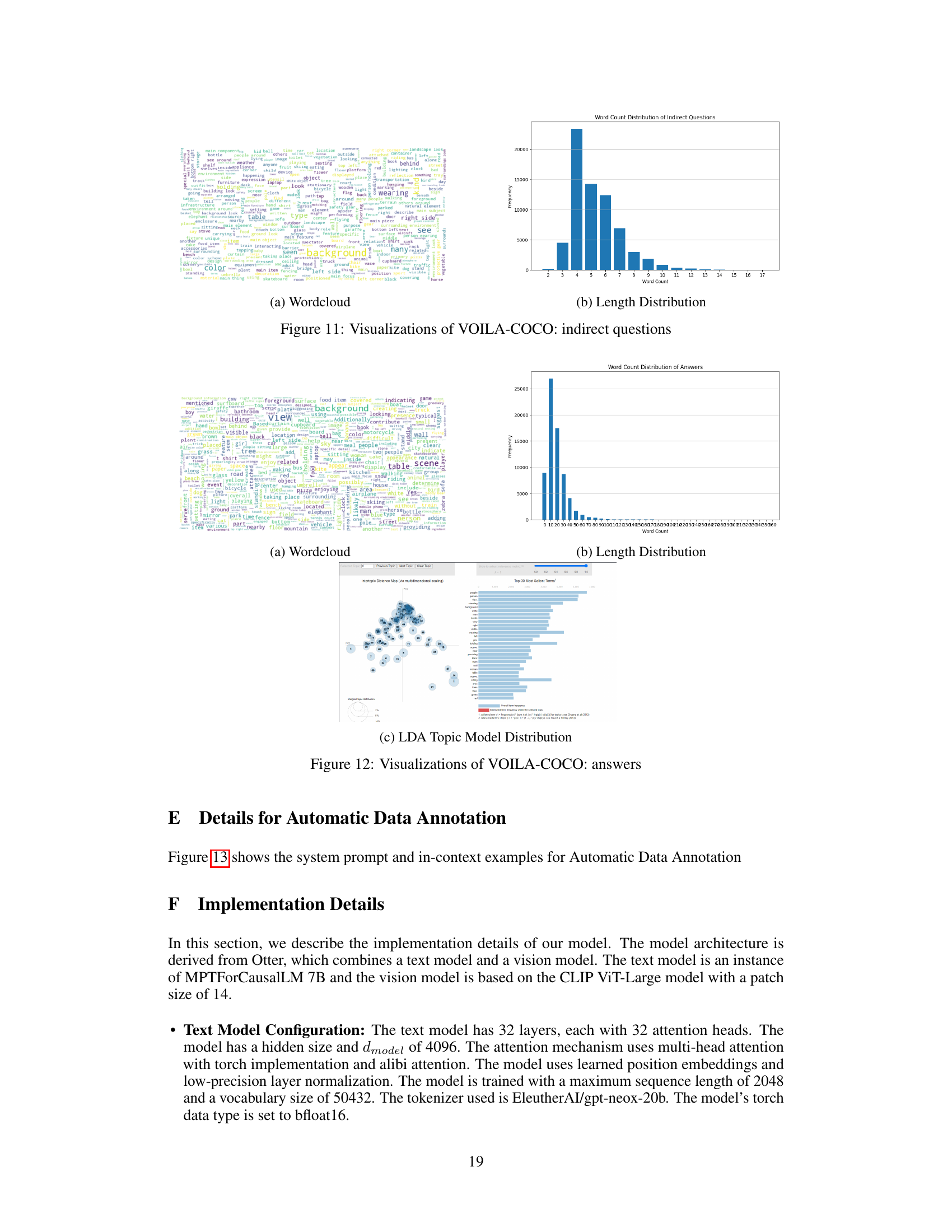

This figure illustrates the pipeline for automatically annotating data using GPT-4. It starts with 100 seed samples from the LN-COCO dataset. The prompt design is iteratively refined (10 iterations) using manual prompt tuning and GPT-4 to ensure helpful, diverse, and well-formatted grounded QA pairs are created. Once the prompt is finalized, the pipeline processes 25k image pairs from LN-COCO, using the refined prompt and GPT-4 to generate raw grounded QA pairs. A post-processing stage filters these pairs based on reward score and keywords, resulting in the final VOILA-COCO dataset of localized QA pairs, incorporating trace data alignment.

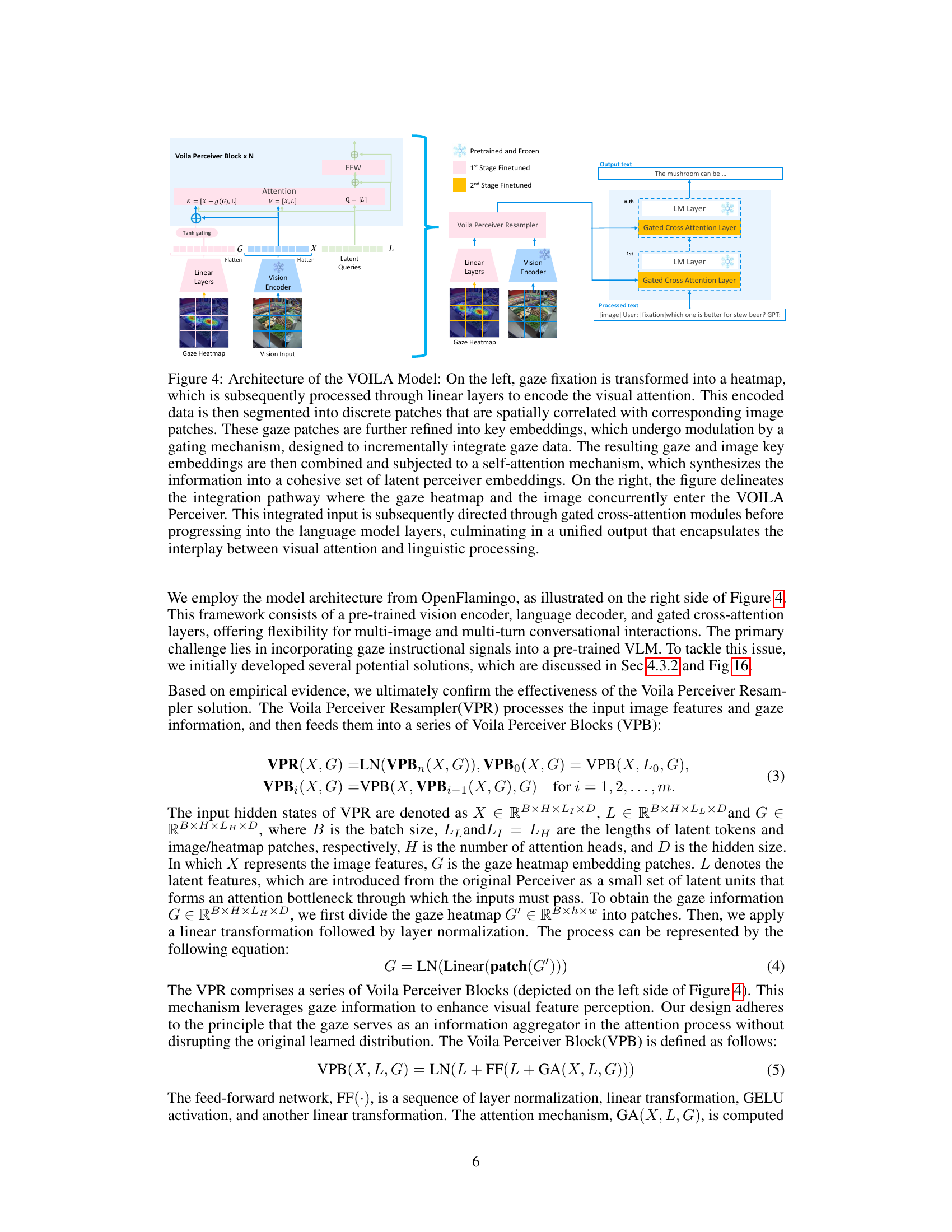

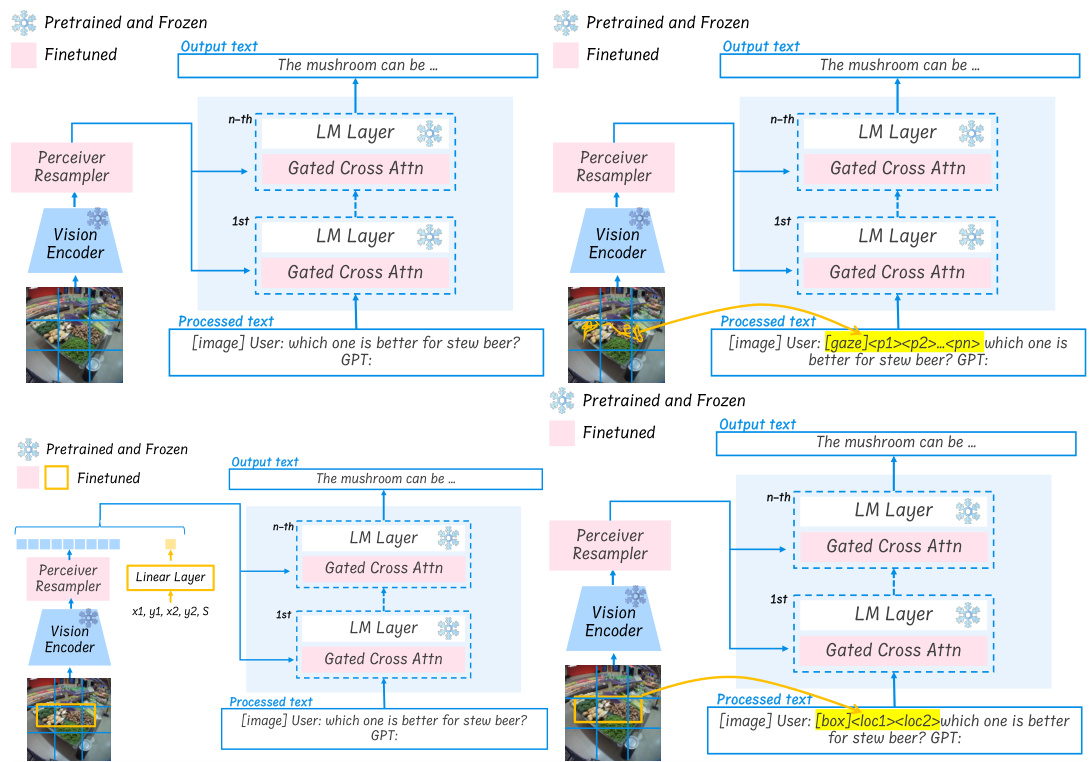

This figure shows the architecture of the VOILA model. The left side illustrates how gaze fixation is processed into key embeddings that are integrated with image patches. The right side shows how the combined gaze and image information is processed through gated cross-attention modules and language model layers to produce a unified output reflecting both visual and linguistic information.

This figure presents a bar chart comparing the performance of three vision-language models: VOILA, Otter, and Kosmos-2, on the VOILA-COCO-Testset. The chart shows the percentage of wins, ties, and losses for each model across three evaluation metrics: Overall, Helpful, and Grounding. The results illustrate VOILA’s superior performance, particularly in terms of helpfulness and grounding capabilities, compared to the baseline models.

The figure shows the results of GPT-RANKING on the VOILA-GAZE test set. It compares the performance of Voila-A against two baseline models (Otter and Kosmos-2) across three aspects: overall performance, helpfulness, and grounding. The bar chart displays the percentage of wins, ties, and losses for each comparison.

This figure shows four different scenarios where a user wearing a head-mounted display interacts with a vision-language model (VLM) by making a gaze-based query. Each scenario showcases the system’s ability to understand and respond accurately to the user’s gaze focus and intent. The scenarios range from simple object identification (e.g., determining the color of cakes) to more complex tasks involving user needs or intentions. The responses from the VLM demonstrate natural language understanding and real-world applicability.

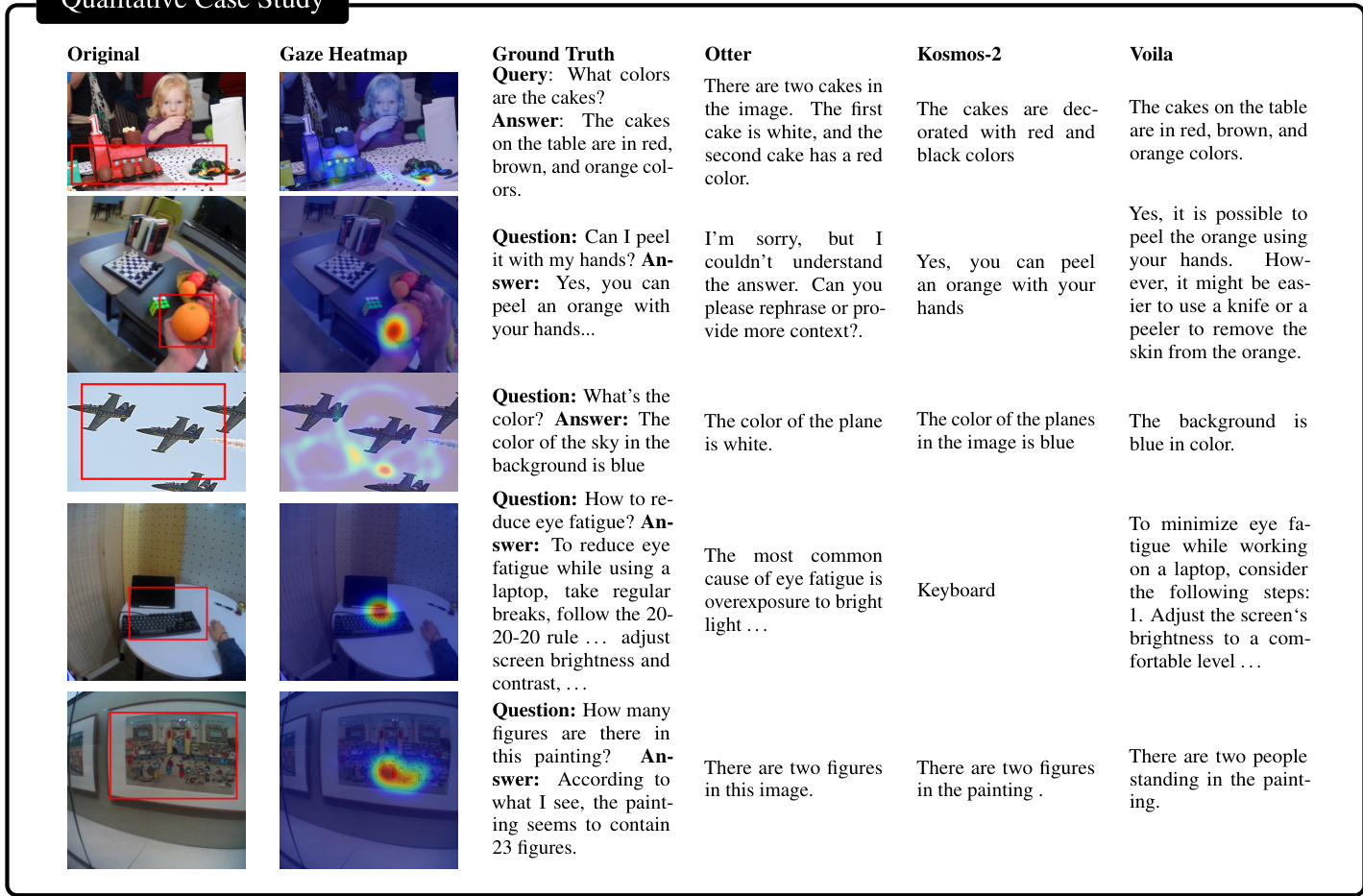

This figure shows a qualitative case study comparing the performance of three different models (Otter, Kosmos-2, and Voila) on various types of questions. The top row shows examples where all models perform well. The middle row highlights scenarios where baseline models struggle with coreference and gaze grounding, while Voila performs well. The bottom row presents challenging scenarios where even Voila faces difficulties.

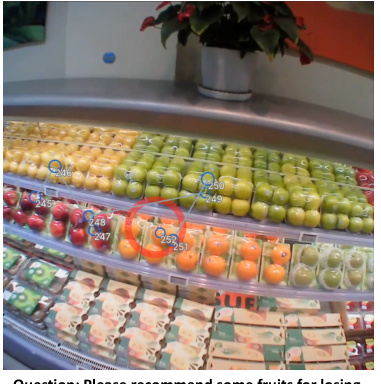

This figure shows example images from the VOILA-GAZE dataset. The images depict real-life scenarios captured using a gaze-tracking device. Each image shows a grocery store shelf with various fruits. The gaze data is overlaid onto the images as points indicating where the user was looking while asking the corresponding questions.

This figure shows three example images from the VOILA-GAZE dataset. Each image shows a scene from a real-world setting (supermarket, museum, and home) and includes gaze data. The gaze data is represented by circles around specific locations that the user was focusing on.

This figure shows example annotations from the VOILA-COCO dataset. Each image shows an egocentric view with gaze points overlaid. The captions and questions demonstrate how gaze data is used to generate relevant and contextually appropriate questions and answers. It highlights the integration of image, gaze, and language to simulate real-world human-AI interactions.

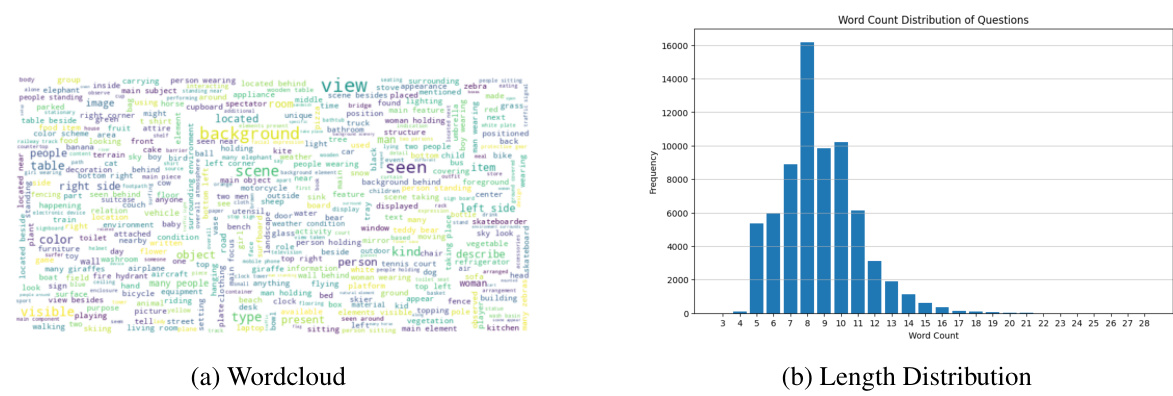

This figure visualizes the word count distribution and length distribution of direct questions from the VOILA-COCO dataset. The wordcloud (a) shows the most frequent words used in the direct questions, giving insight into the common topics and vocabulary. The histogram (b) displays the frequency of questions with different word counts, showing the distribution of question lengths in the dataset.

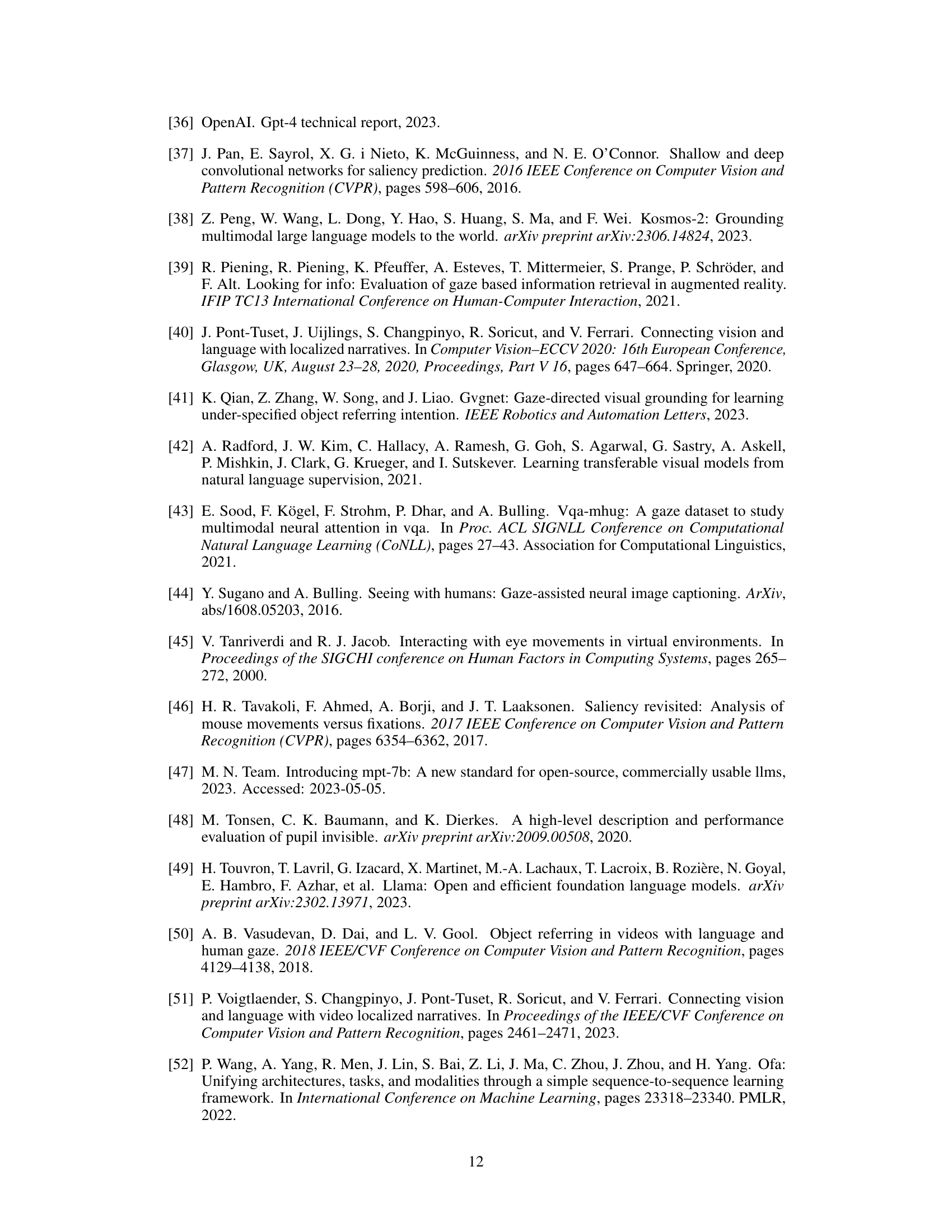

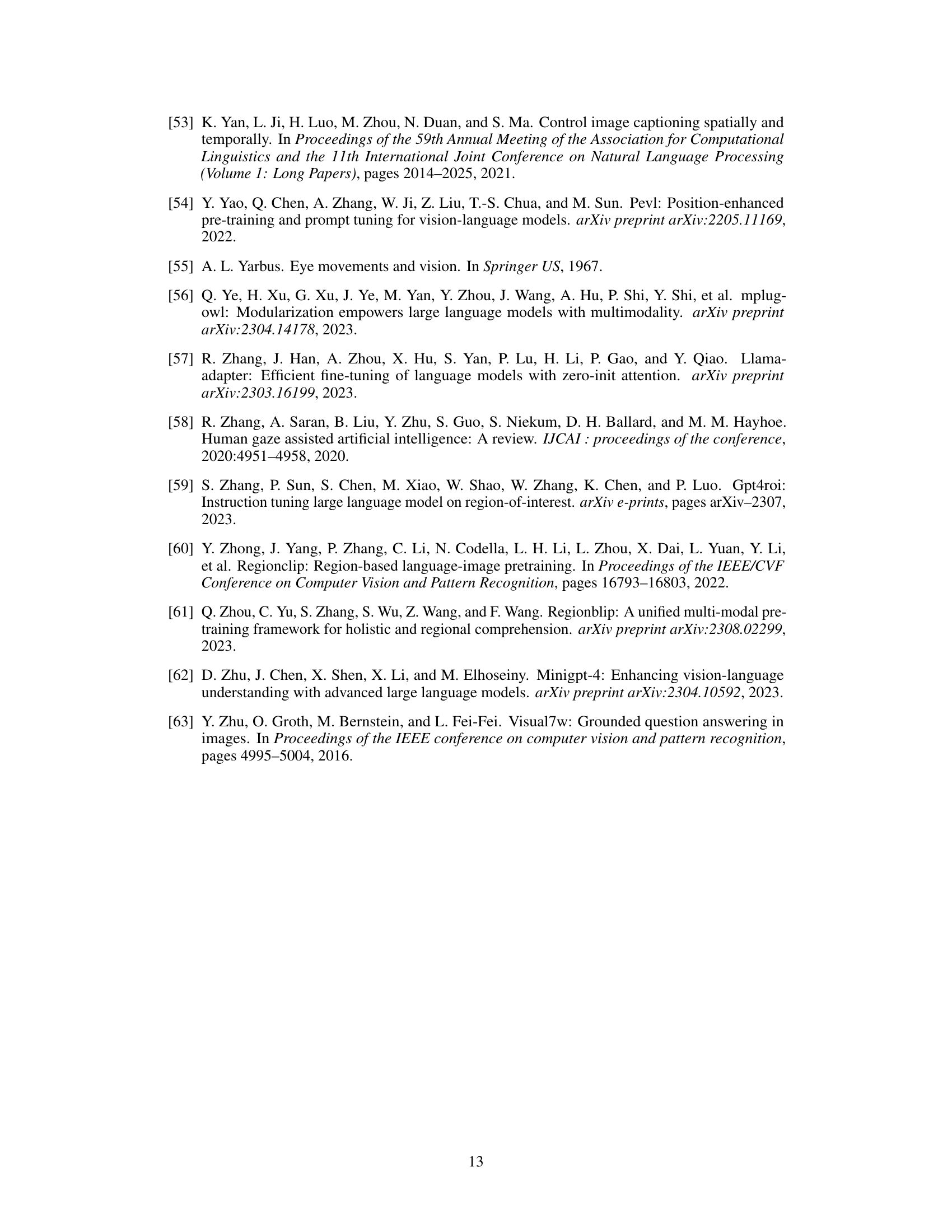

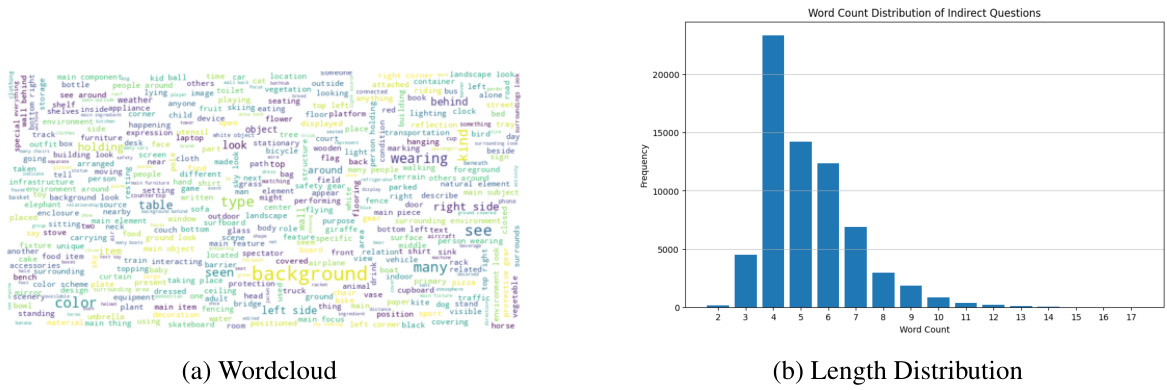

This figure visualizes the indirect questions from the VOILA-COCO dataset. It shows two sub-figures: (a) Wordcloud, which displays a visual representation of the frequency of words used in the indirect questions; and (b) Length Distribution, which presents a histogram showing the distribution of the number of words per indirect question.

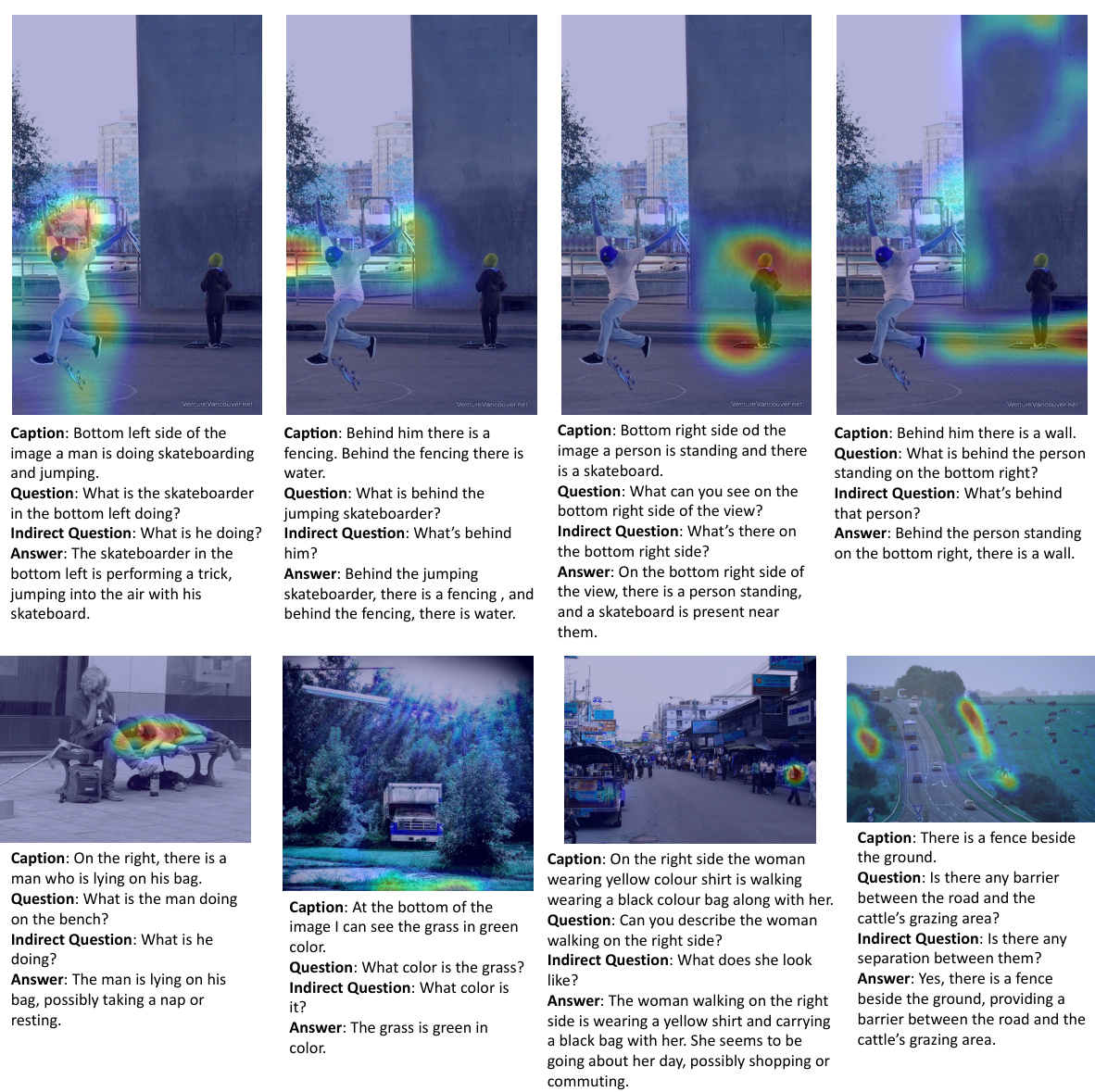

This figure shows several annotated examples from the VOILA-COCO dataset. Each example includes an image, a gaze heatmap, a caption describing the image, a question about the image, an indirect version of the question (more conversational), and a generated answer. The examples demonstrate the pipeline’s ability to generate accurate and relevant answers based on the image and gaze information.

This figure shows several examples from the VOILA-COCO dataset. Each example consists of an image, a gaze heatmap, a caption generated by a human, a question asked by the human, an indirect question that reflects the human’s gaze focus, and finally, an answer to both the original question and the indirect question. The examples illustrate the diverse scenarios and complexities covered in the dataset.

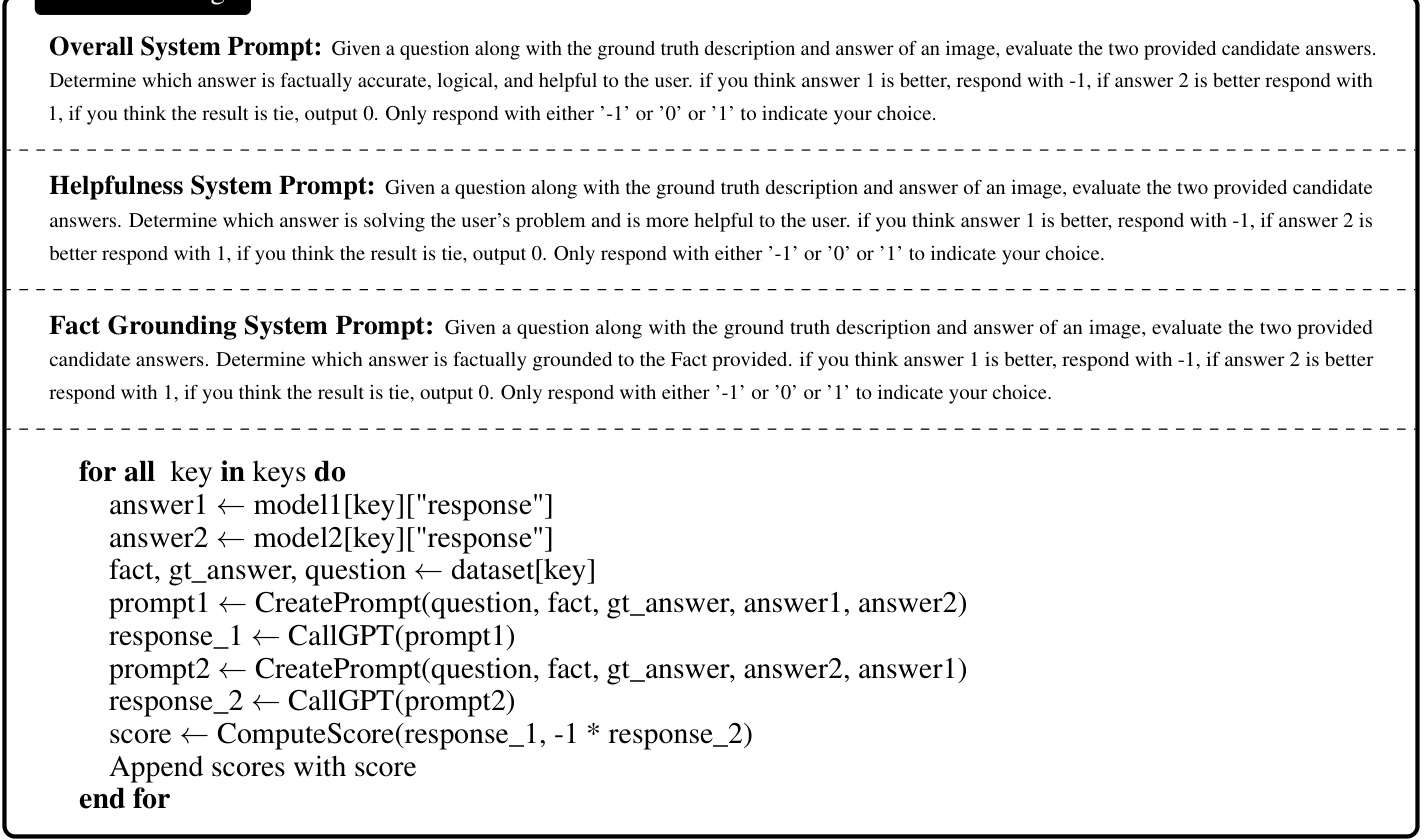

The figure shows the pseudocode for the GPT-4 ranking procedure used to evaluate the models. The procedure takes as input a list of keys corresponding to question-answer pairs. For each key, it retrieves the responses from two models, model1 and model2. It then constructs two prompts for GPT-4, one with answer1 preceding answer2, and the other with answer2 preceding answer1. The GPT-4 responses are used to compute a score, which is then appended to a list of scores. The final list of scores represents the GPT-4 ranking evaluation of the two models.

This figure illustrates the architecture of the VOILA model, showing how gaze information is integrated with image features to improve vision-language model performance. The left side depicts the processing of gaze data into key embeddings, which are then combined with image embeddings and fed into a self-attention mechanism. The right side details how this combined information is integrated into the language model to generate a unified output.

More on tables

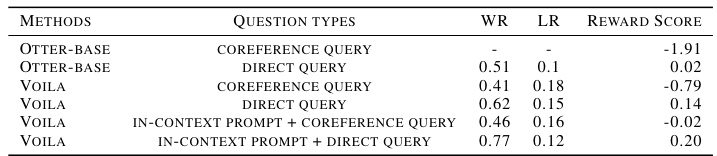

This table presents the results of an ablation study on different query types (direct and coreference) and their impact on the model’s performance. It compares the winning rate (WR), loss rate (LR), and reward scores for Otter-base and VOILA models across different question types. Additionally, it shows the results with in-context prompts to demonstrate the impact of adding contextual information on the model’s ability to handle coreference queries.

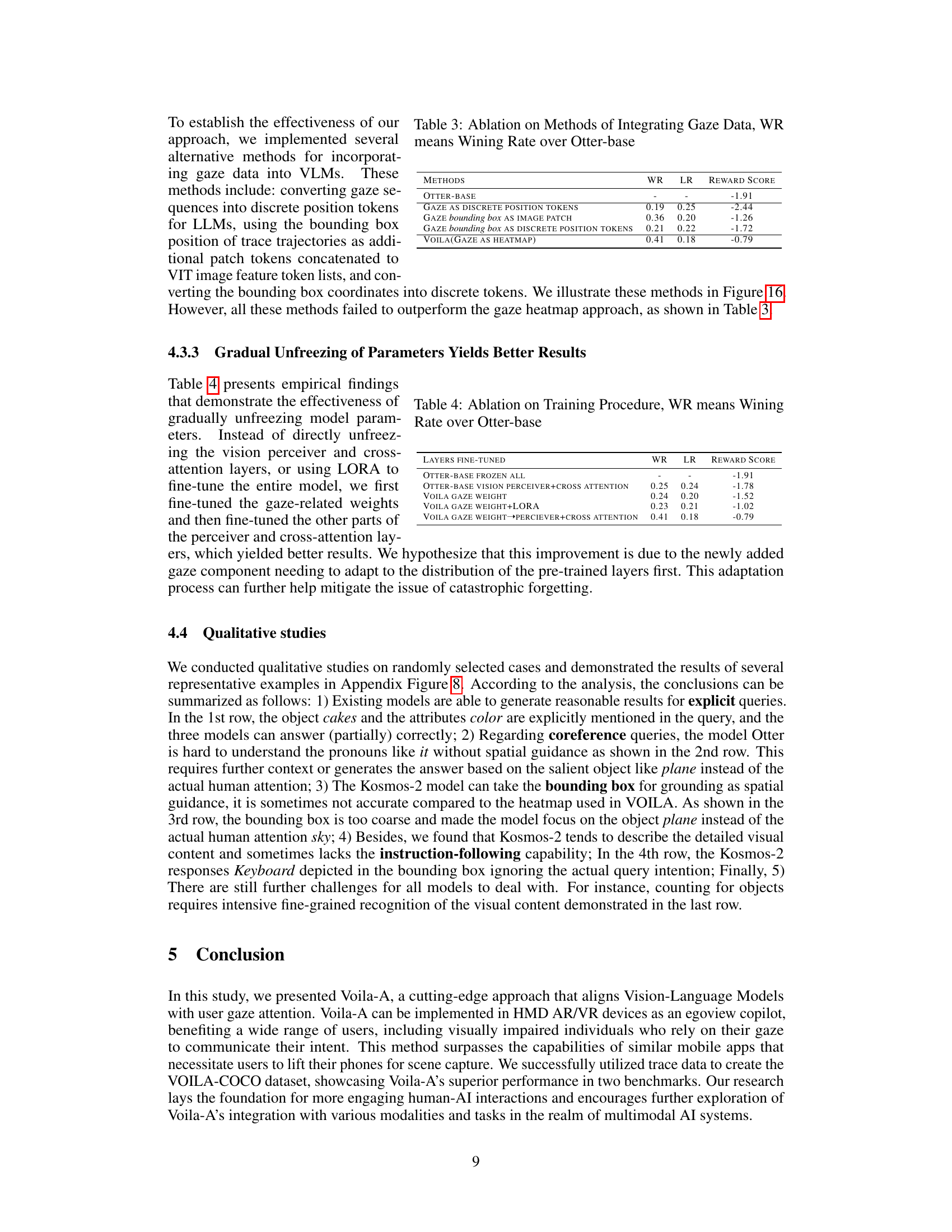

This table presents the results of ablation studies comparing different methods of integrating gaze data into the Vision-Language Model (VLM). The methods compared include using gaze as discrete position tokens, gaze bounding box as image patches, gaze bounding box as discrete position tokens, and the proposed Voila method which uses gaze as a heatmap. The results are presented in terms of winning rate (WR), loss rate (LR), and reward score, all relative to the Otter-base model.

This table presents the results of ablation studies on the training procedure of the VOILA model. It compares the performance of different fine-tuning strategies on the model’s ability to align vision-language models with the user’s gaze attention. The strategies involve fine-tuning different layers (gaze weight only, gaze weight + LoRA, and gaze weight + perceiver + cross-attention) and freezing all layers in the baseline Otter model. The performance is measured using winning rate (WR), learning rate (LR), and reward score, with VOILA’s approach achieving the best performance.

This table presents the statistics for the VOILA-COCO and VOILA-GAZE datasets, showing the number of images and questions in each split (training, validation, test). The Survival Rate (SR) indicates the percentage of raw data retained after filtering steps during data annotation and curation.

Full paper#