↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current computer vision models prioritize efficiency over biological realism, using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) despite their limitations in accurately capturing temporal dynamics inherent in biological systems. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) offer better temporal modeling but are less efficient for visual processing. This research addresses this by introducing CordsNet, a hybrid model that combines the spatial processing prowess of CNNs with the temporal dynamics of RNNs.

CordsNet effectively integrates continuous-time recurrent dynamics into a CNN framework. The researchers developed a novel training algorithm to improve computational efficiency. They demonstrate its superior performance on image recognition benchmarks, showing improved robustness to noise and better prediction of neural activity in biological vision systems compared to conventional CNNs. This shows the benefits of combining different model architectures to achieve better results for biological vision systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in computer vision and neuroscience because it bridges the gap between Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), offering a novel hybrid architecture that combines the strengths of both. This has significant implications for building more biologically plausible and robust vision systems, opening new avenues for understanding the brain’s visual processing mechanisms. The proposed methods for training and analyzing the hybrid model are also valuable contributions, offering improved efficiency and insights into the dynamics of the system.

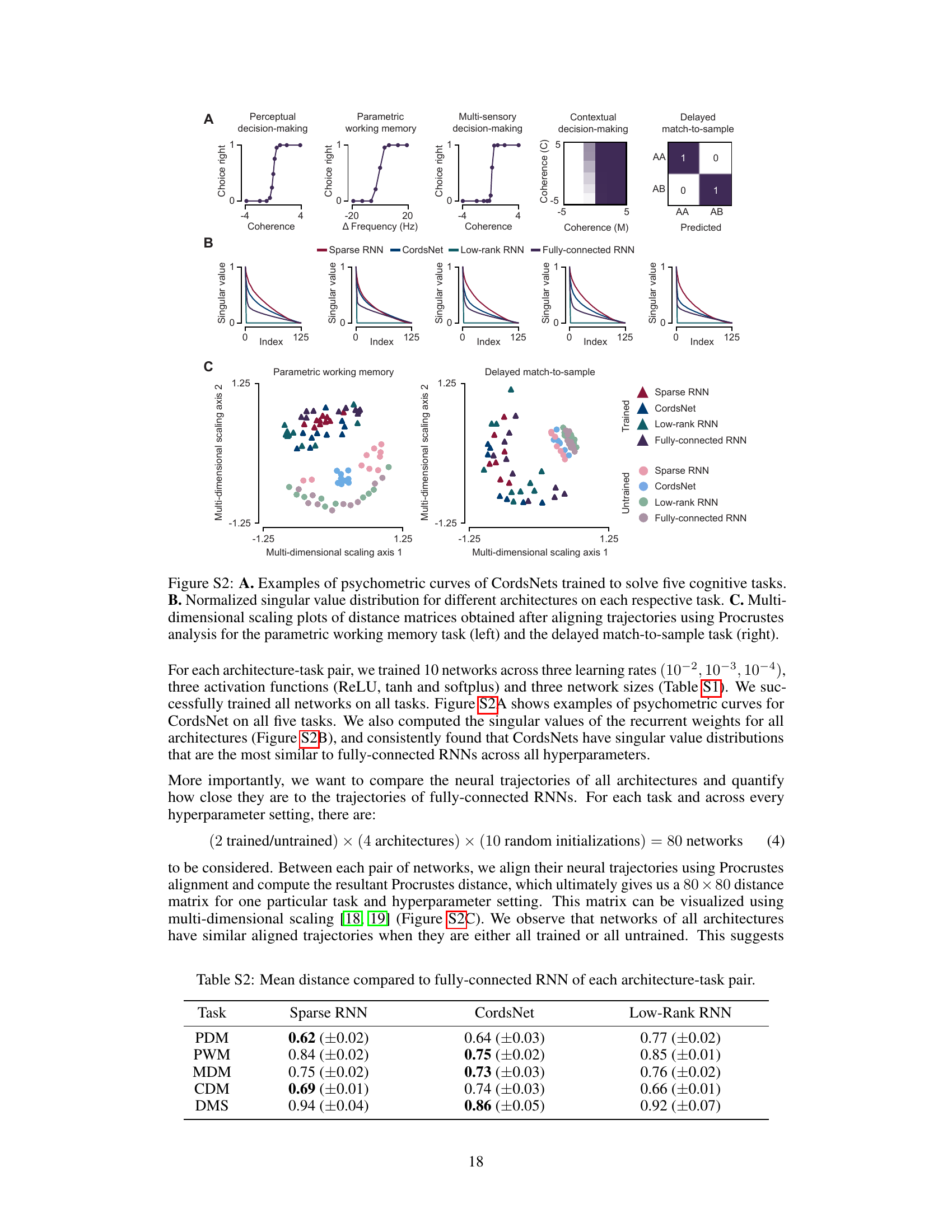

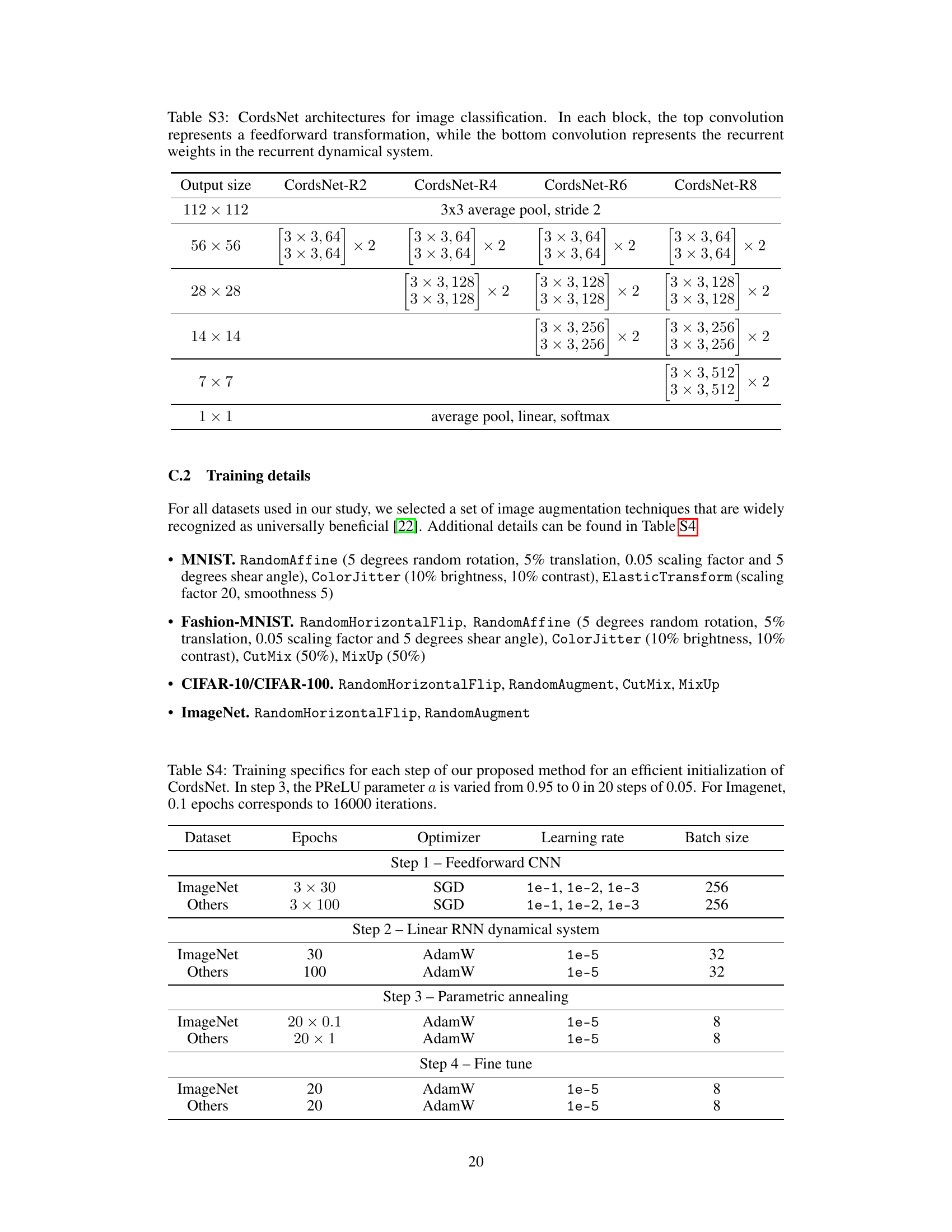

Visual Insights#

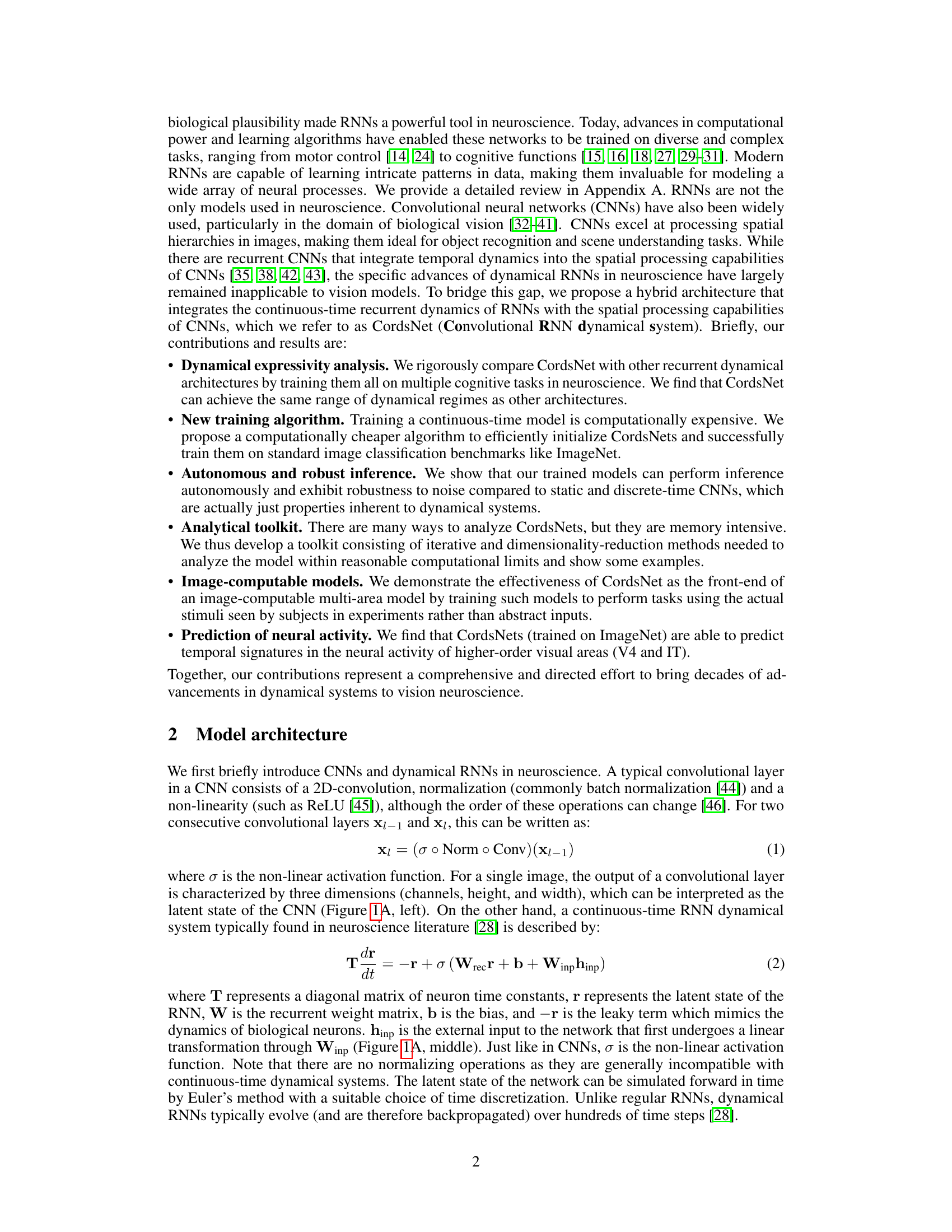

This figure provides a visual overview of the proposed CordsNet architecture and its relationship to traditional CNNs and RNNs. Panel A shows a comparison of the three architectures. Panel B illustrates the various dynamic regimes that CordsNet can exhibit, including stable, oscillatory, and chaotic patterns of neural activity. Panels C and D demonstrate the ability of CordsNet to produce similar dynamical results to other RNN architectures and to successfully perform the memory-pro delayed response task, respectively.

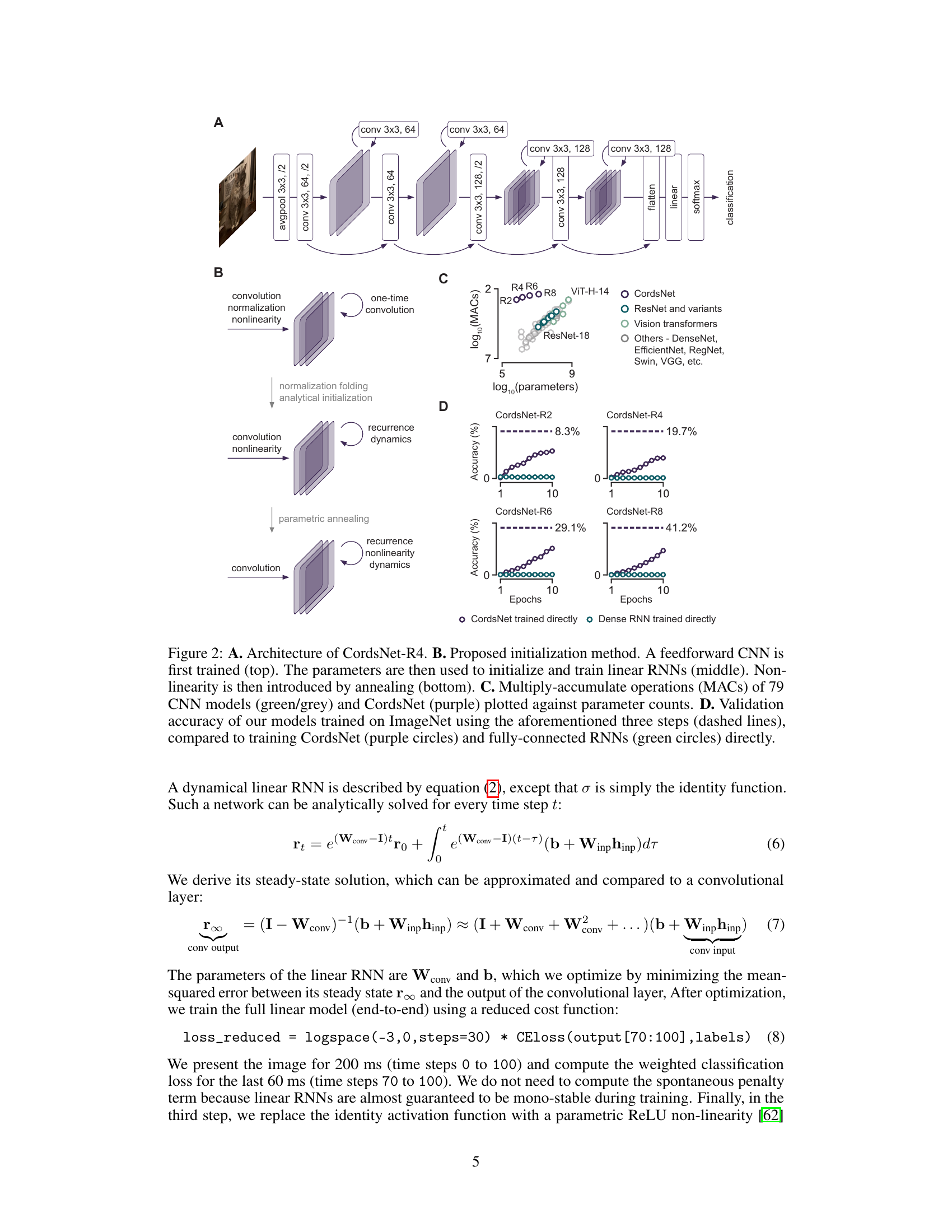

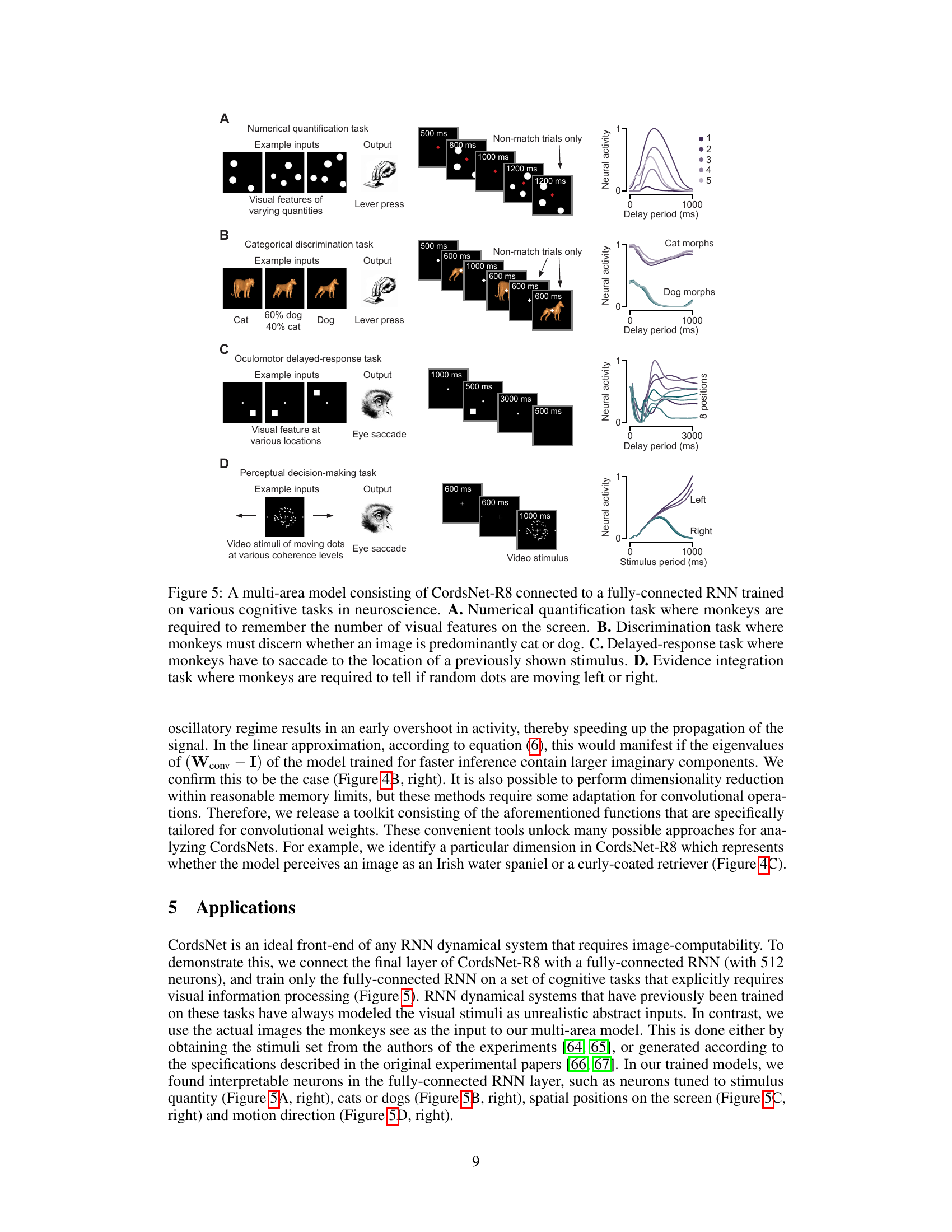

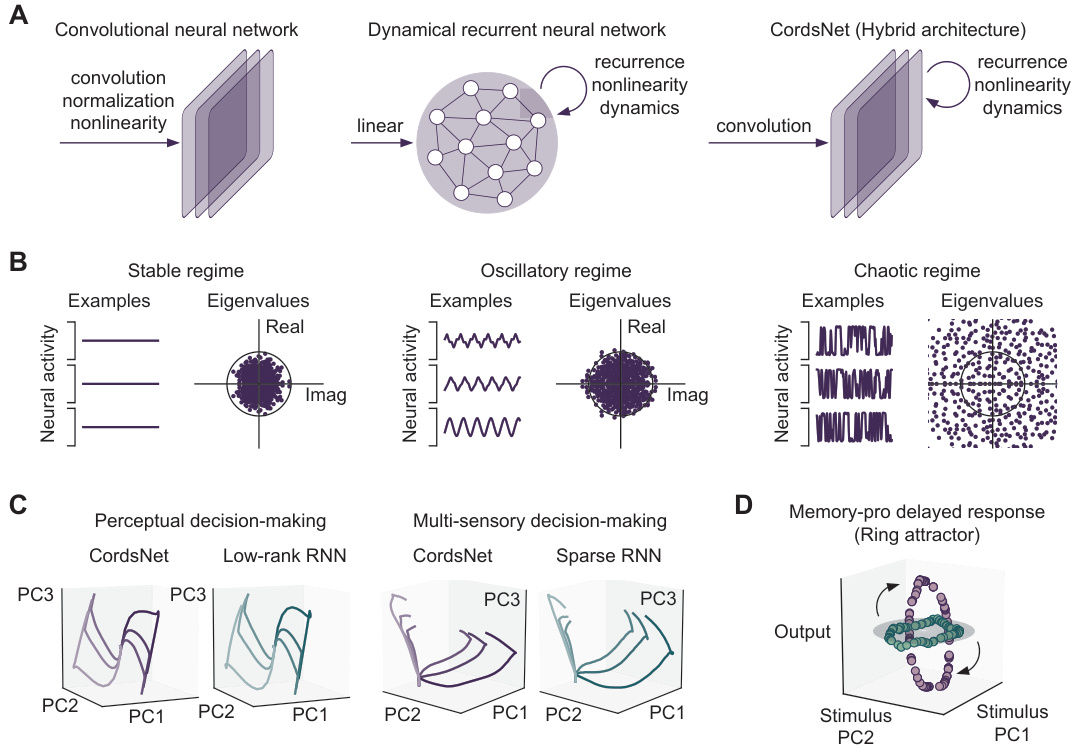

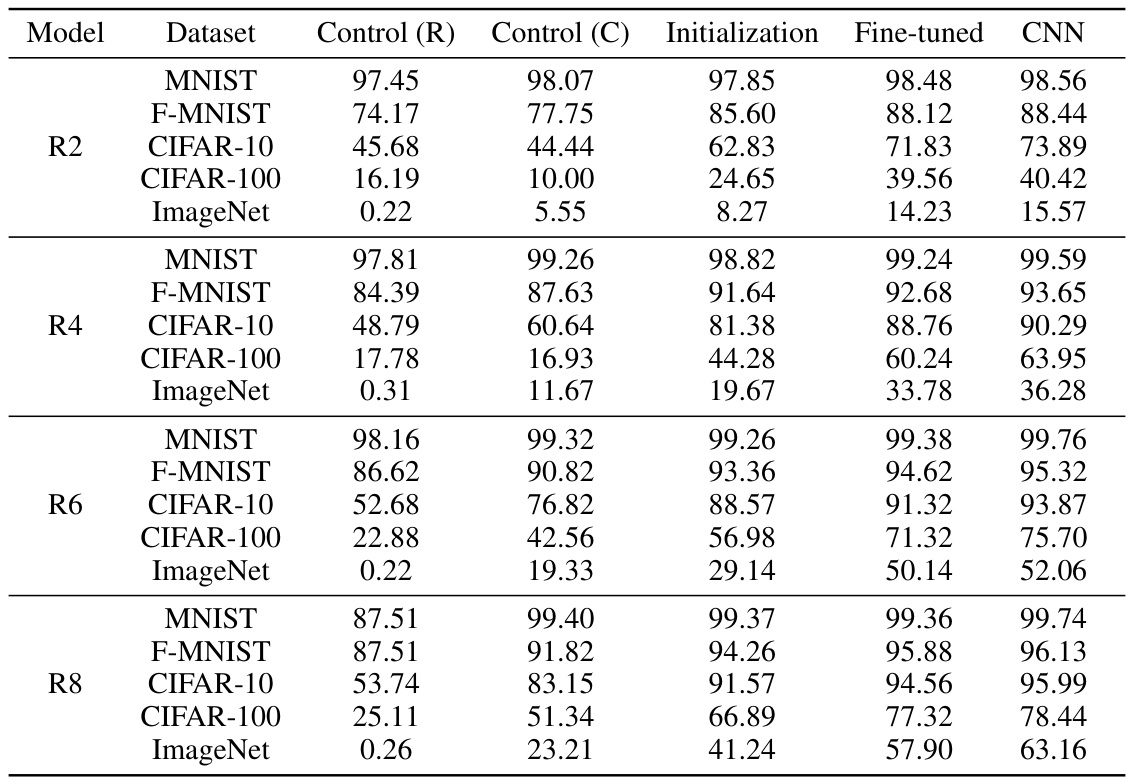

This table presents the test accuracies achieved by CordsNets (trained using the proposed initialization method and after fine-tuning) on various datasets (MNIST, F-MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, ImageNet). The results are compared against those of equivalent feedforward CNNs, as well as control groups using CordsNets trained directly (for the same amount of time as the initialization method) and fully-connected RNNs (with matched parameter counts). The table shows how the initialization method improves performance compared to directly training the model and that performance is comparable to CNNs after fine-tuning.

In-depth insights#

Hybrid CNN-RNN Arch#

A hybrid CNN-RNN architecture merges the strengths of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for enhanced performance in visual tasks. CNNs excel at spatial feature extraction, while RNNs capture temporal dynamics. This combination aims to overcome limitations of using CNNs alone, such as difficulties in modeling time-dependent information in video or sequential image data. By incorporating RNN layers after the CNN layers, the model can leverage the extracted spatial features for temporal processing, improving accuracy and robustness. A key challenge is effective training of such a hybrid network, requiring efficient algorithms that manage the computational complexity of both CNN and RNN components. The architecture’s success hinges on demonstrating improved performance on benchmark datasets and potentially revealing new biological insights into visual processing. The integration of spatial and temporal processing capabilities promises significant advances in AI applications. However, this architecture needs to address the increased computational cost compared to purely CNN-based methods.

Dynamical Expressivity#

The concept of “Dynamical Expressivity” in the context of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for biological vision refers to the range and richness of temporal dynamics these networks can exhibit. It’s crucial because biological neural systems display a vast array of dynamic behaviors, from stable states to oscillations and even chaos. A highly expressive RNN should be able to mimic this diversity, allowing it to model various neural processes accurately. The paper likely investigates whether a specific RNN architecture, possibly one combining convolutional and recurrent components, can achieve sufficient dynamical expressivity. This involves analyzing the model’s behavior under various conditions (e.g., different inputs, parameter settings), examining the resulting activity patterns (e.g., using dimensionality reduction, analyzing eigenvalues and eigenvectors), and comparing them to the known dynamic regimes of other RNNs. Demonstrating adequate dynamical expressivity is critical for validation, suggesting the model’s plausibility as a biologically realistic model of visual processing.

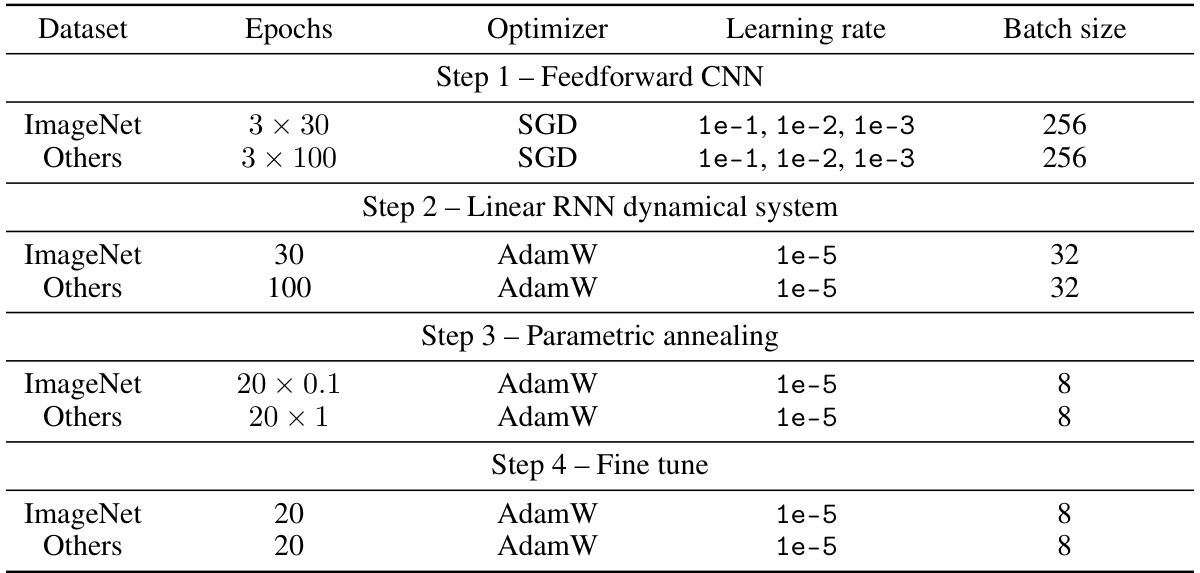

Training & Inference#

The training and inference phases are crucial for evaluating the efficacy of recurrent neural networks (RNNs). Training focuses on efficiently initializing and training continuous-time models, which is computationally expensive. The authors address this challenge by developing a computationally cheaper algorithm that leverages a three-step process: first training a feedforward CNN, then folding batch normalization into convolution operations to initialize linear RNNs, and finally introducing a parametric ReLU non-linearity via annealing. Inference in the proposed architecture, CordsNet, is autonomous and robust to noise, owing to inherent noise-suppressing mechanisms in recurrent dynamical systems, unlike static CNNs. This characteristic significantly enhances performance even with noisy inputs. The model exhibits increased robustness to noise making it highly suitable for real-world applications. The authors’ developed analytical toolkit facilitates efficient analysis despite the computational cost of analyzing convolutional structures. Thus, CordsNet successfully combines the strengths of CNNs for spatial processing with the superior temporal dynamics of RNNs, achieving competitive results in image recognition tasks while maintaining biological realism.

Noise Robustness#

The research paper analyzes the noise robustness of a novel hybrid architecture, CordsNet, by evaluating its performance under various noise levels. CordsNet’s inherent recurrent dynamics act as a noise-suppressing mechanism, improving its robustness compared to conventional CNNs. This robustness stems from the continuous-time nature of the model and its ability to integrate information over time, effectively filtering out noise. The paper demonstrates this enhanced robustness quantitatively using metrics such as mean-squared error and validation accuracy on noisy images, showing that CordsNet maintains higher accuracy at high noise levels. This noise robustness is a crucial advantage, especially in real-world applications where noisy or imperfect data is prevalent. The results highlight the potential of dynamical systems for developing more robust and reliable AI models for various applications, including biological vision.

Biological Modeling#

Biological modeling in the context of neural networks aims to create artificial systems that mirror the structure and function of biological neural systems. This involves translating biological principles into computational models, often using recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to capture the inherent dynamics of neural activity. A key challenge is balancing biological realism with computational tractability. While highly detailed biophysical models offer high fidelity, they are computationally expensive and difficult to train. Simpler models, like integrate-and-fire neurons or rate-based models, offer better scalability but may sacrifice biological detail. Therefore, the choice of model complexity involves a trade-off between accuracy and practicality. The success of biological modeling hinges on the ability of the model to reproduce experimental observations, such as neural firing patterns, behavior in cognitive tasks, and responses to sensory stimuli. Ultimately, successful biological modeling can lead to a deeper understanding of the brain’s computational principles and inspire new artificial intelligence architectures with improved efficiency and performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

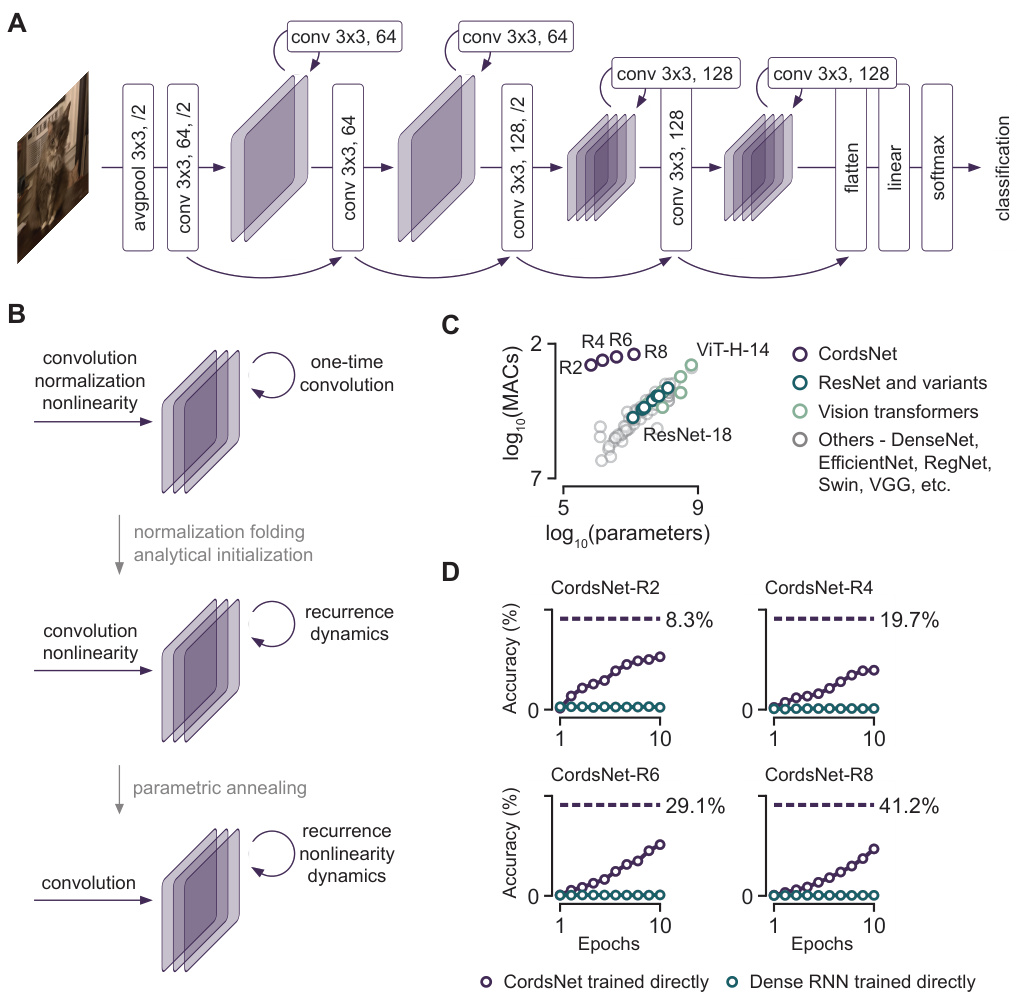

This figure shows the architecture of CordsNet-R4, a hybrid model that combines convolutional and recurrent neural network features. It also details the proposed three-step initialization method, comparing the computational cost (MACs) of CordsNet with other CNN models and illustrating the validation accuracy on ImageNet.

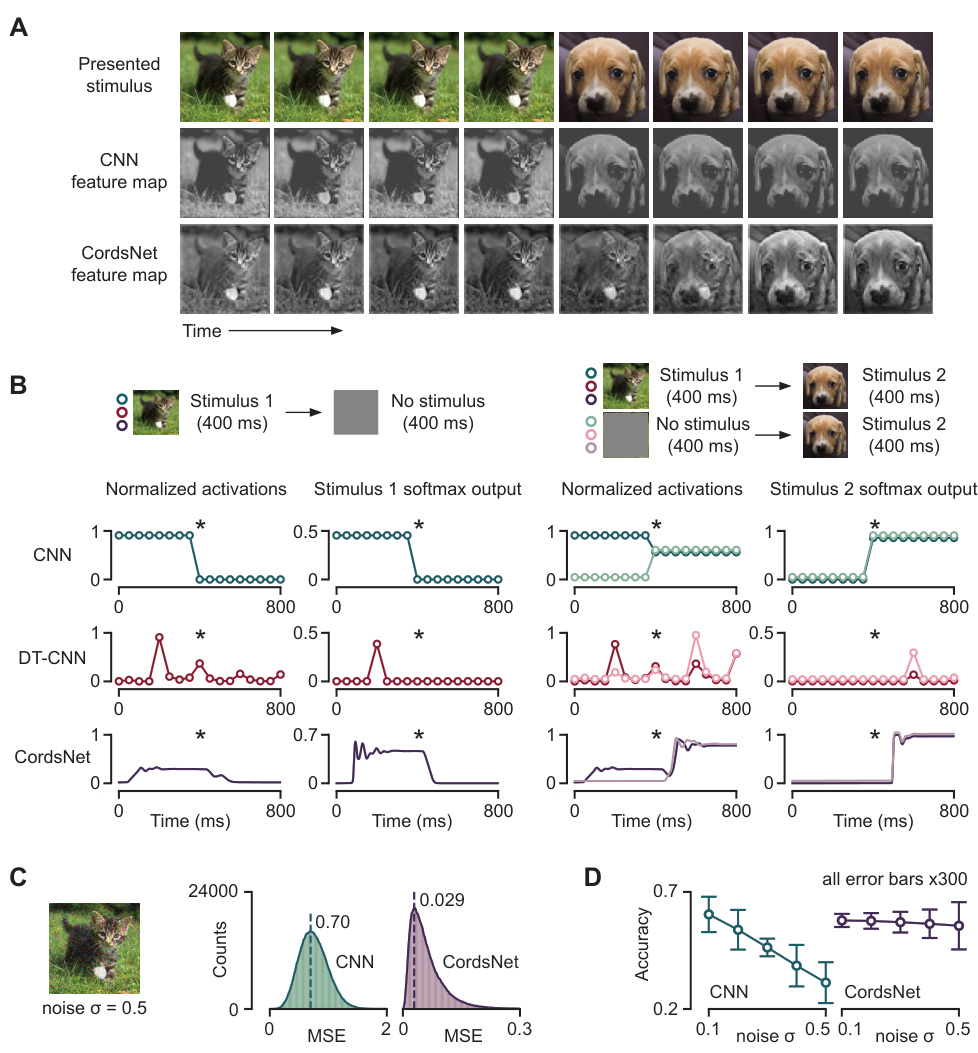

This figure demonstrates the temporal dynamics of CordsNet compared to other CNN architectures. Panel A shows how a single feature map evolves over time in CordsNet, highlighting its continuous-time nature. Panel B compares the neural activity and softmax output of CordsNet, a feedforward CNN, and a discrete-time CNN under different stimulus sequences. C shows the robustness of CordsNet to noise by measuring the mean-squared error between its noisy and noiseless activations. Finally, panel D shows the validation accuracy of CordsNet on ImageNet across various noise levels, demonstrating its superior robustness to noise compared to traditional CNNs.

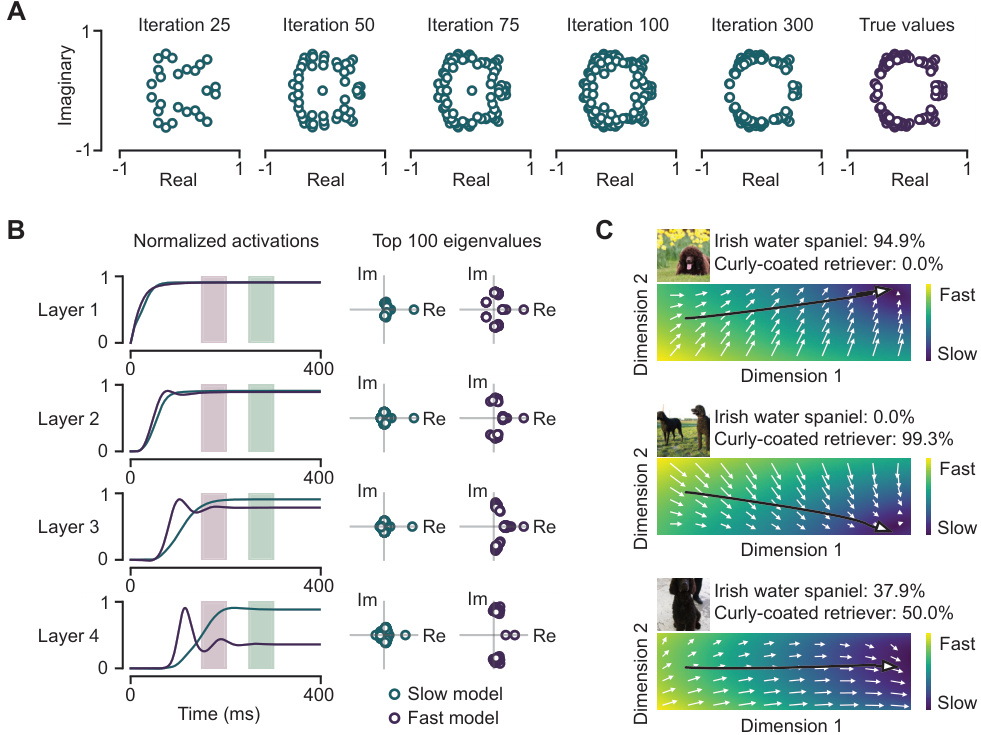

This figure demonstrates the analysis of CordsNet from a dynamical systems perspective. Panel A shows the application of Arnoldi iteration to analyze the convolutional recurrent weight matrix. Panel B shows model activations and eigenvalues for CordsNet-R4 trained to classify images at different time intervals, highlighting the different dynamical characteristics exhibited depending on the training time. Panel C visualizes neural trajectories from the final layer of CordsNet-R8, projected onto two dimensions, for three different images, showcasing the model’s ability to perform autonomous inference.

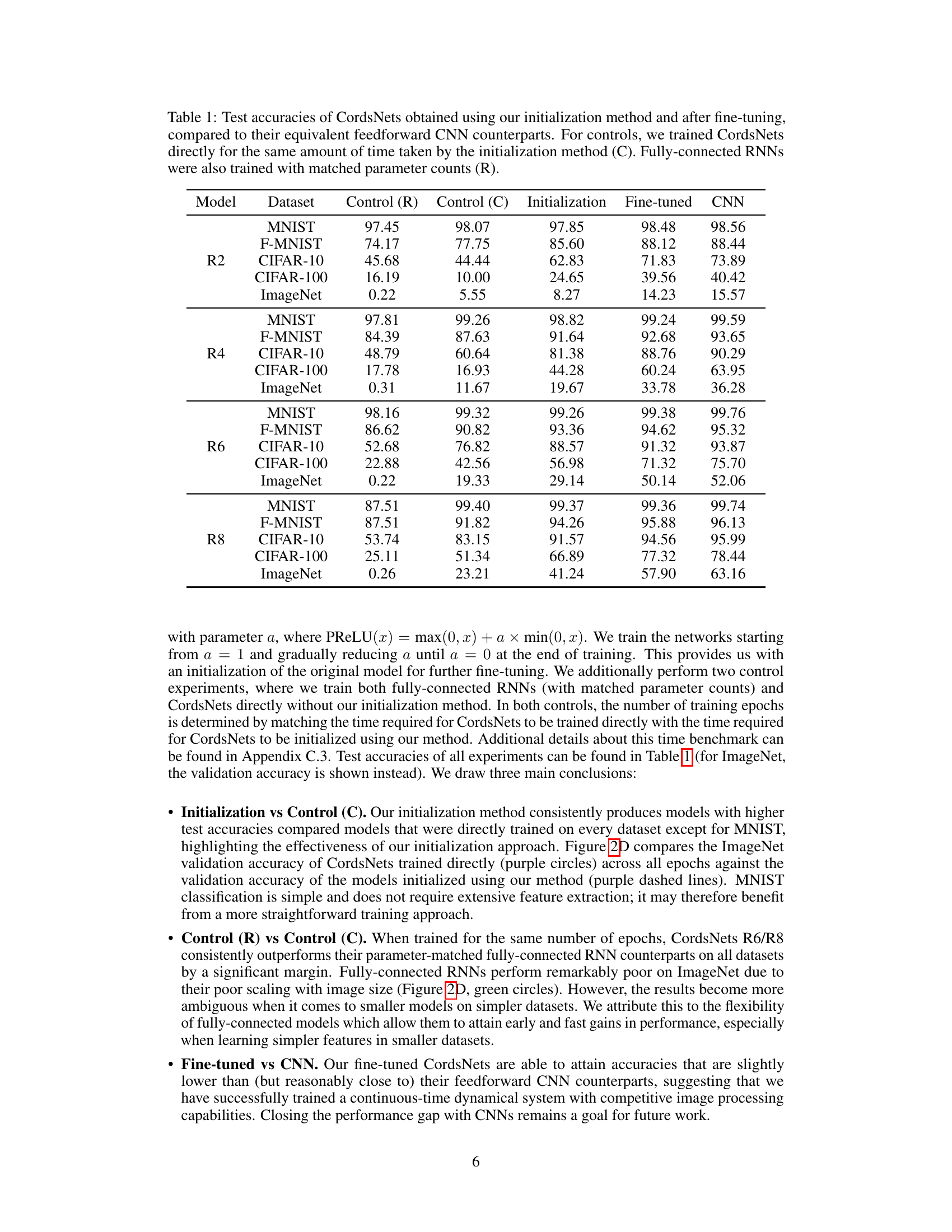

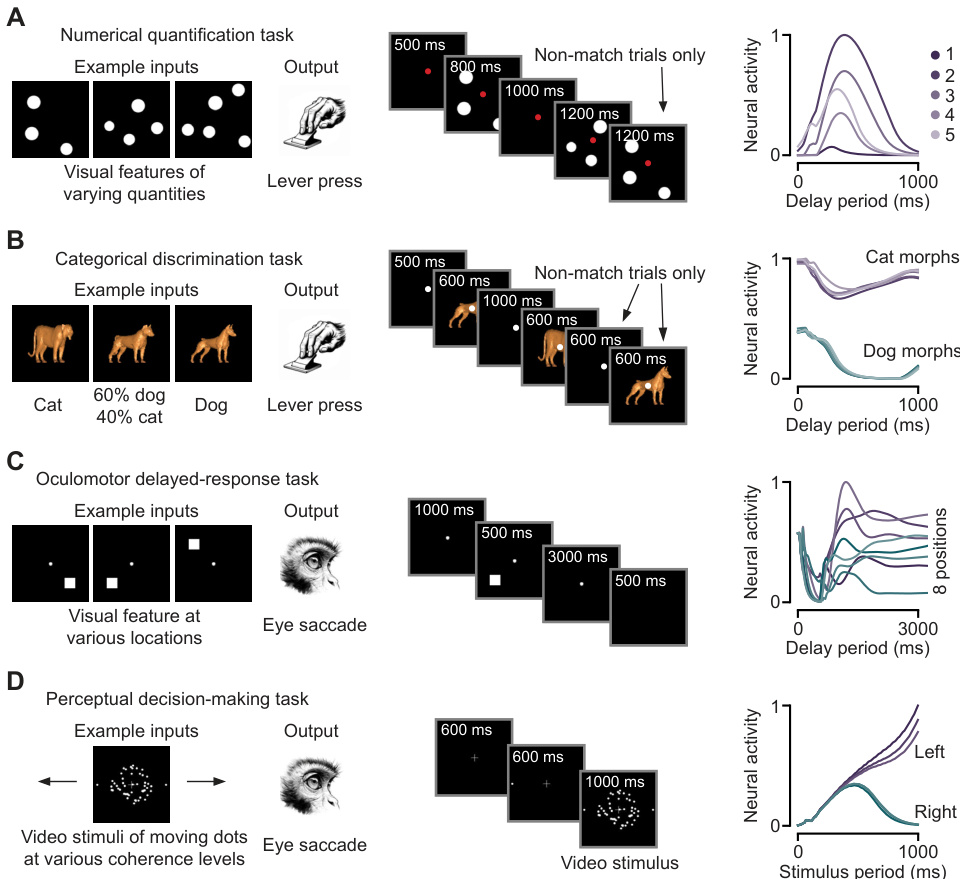

This figure demonstrates the application of CordsNet as a front-end for a multi-area model performing complex cognitive tasks. Four different tasks are shown: a numerical quantification task, a categorical discrimination task, an oculomotor delayed-response task, and a perceptual decision-making task. Each panel shows example inputs, the expected output, and neural activity plots demonstrating the model’s performance on each task. The tasks use actual stimuli from monkey experiments rather than abstract representations, showcasing the model’s capacity to handle naturalistic visual inputs.

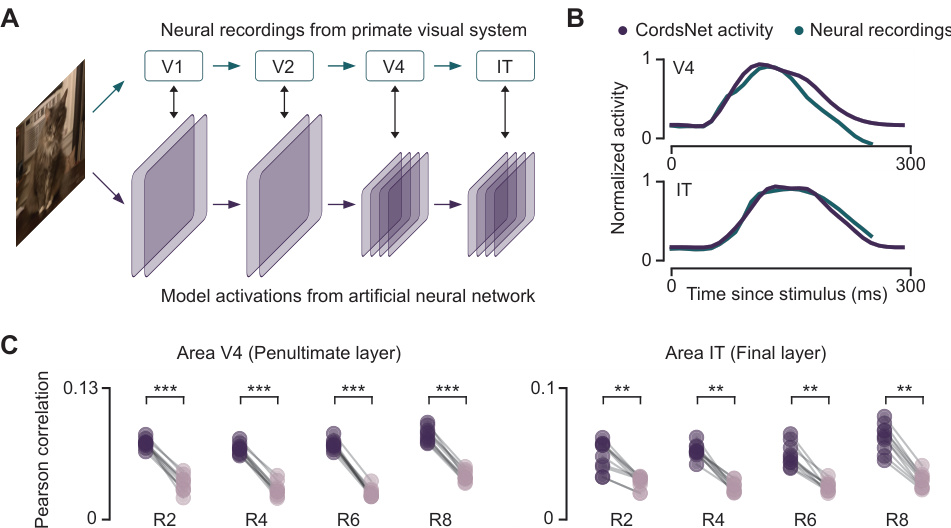

This figure demonstrates the ability of the CordsNet model to predict the temporal dynamics of neural activity in the visual cortex. Panel A illustrates the experimental setup, showing the flow of visual information from V1 to IT and how CordsNet’s activity is compared to neural recordings. Panel B displays the time courses of CordsNet’s activity compared with real neural recordings in V4 and IT, showing that the model replicates the pattern of activity. Finally, panel C quantitatively assesses the similarity between the model and the experimental data using correlation metrics and shows statistically significant similarity.

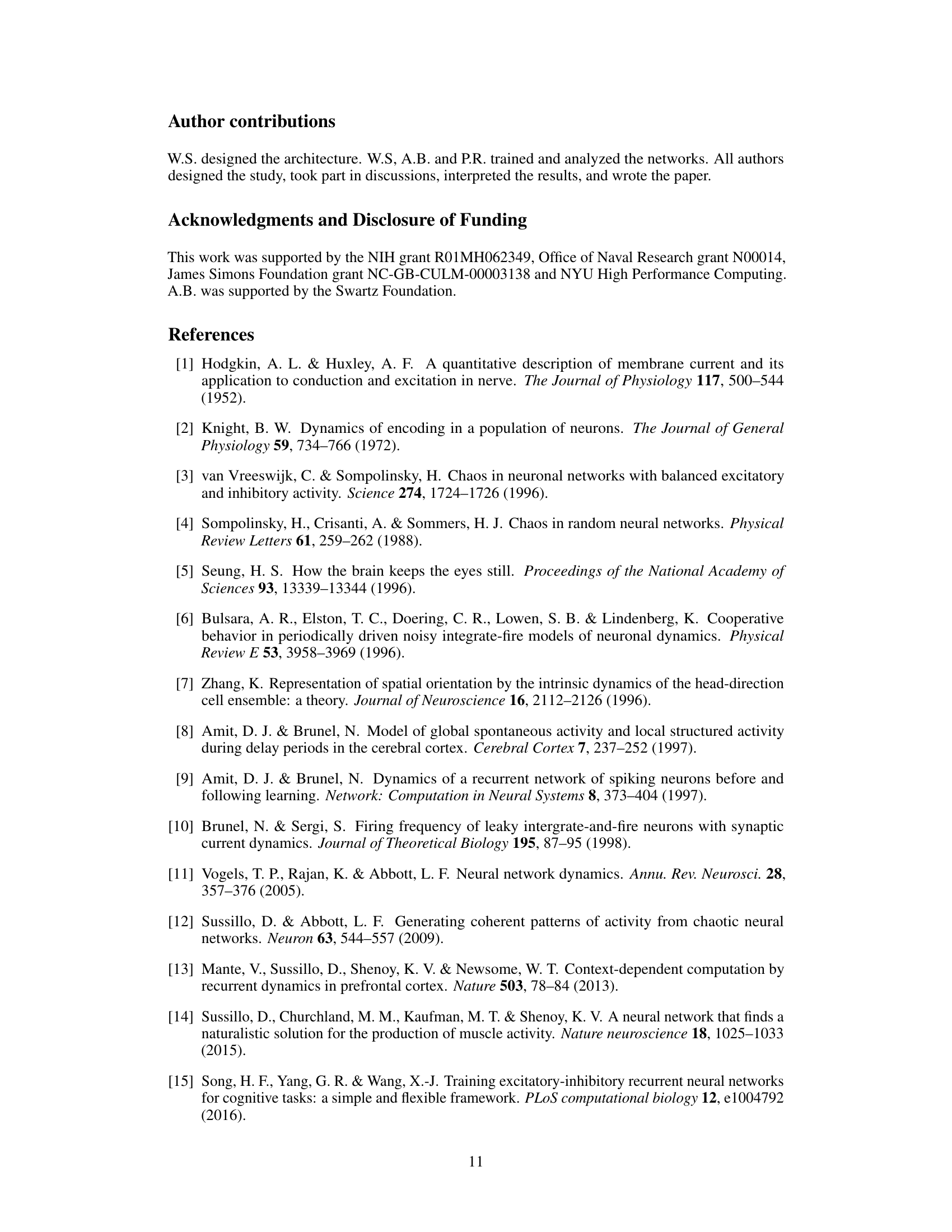

This figure demonstrates the dynamical characteristics of CordsNets by showing the distribution of singular values for different kernel sizes (A) and analyzing the activity patterns in the oscillatory and chaotic regimes (B). In the oscillatory regime, activity shows a periodic pattern in low-dimensional space, whereas in the chaotic regime, the activity is aperiodic and unpredictable.

This figure shows the architecture of CordsNet-R4, a hybrid model that combines convolutional and recurrent neural network components. It also details the proposed initialization method, which involves training a feedforward CNN, initializing linear RNNs with its parameters, and then introducing non-linearity through annealing. The figure further compares the computational efficiency of CordsNet with other CNNs based on MACs and parameter counts. Finally, it contrasts the ImageNet validation accuracy of CordsNet trained using this method with that of directly trained CordsNets and fully-connected RNNs.

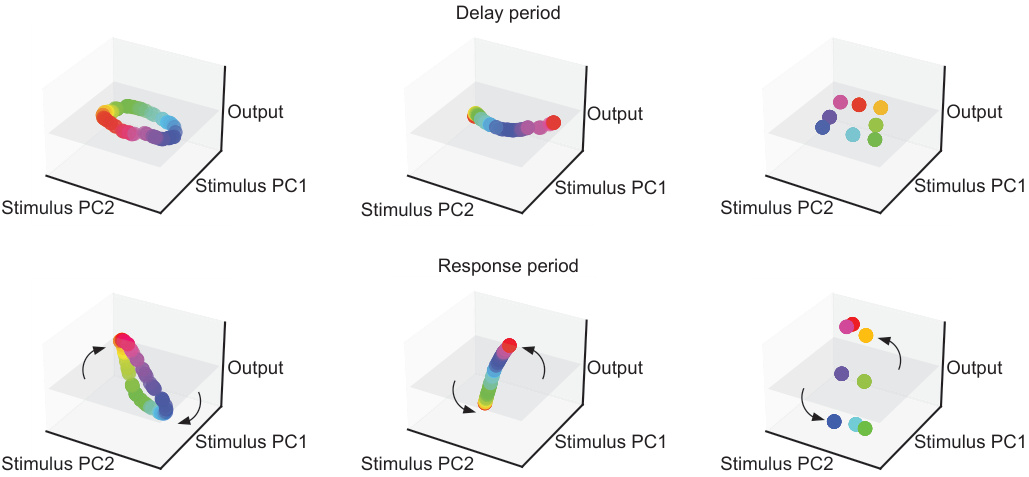

This figure demonstrates the different types of attractor dynamics exhibited by CordsNets during a memory-pro delayed-response task. Depending on the stimulus, the network’s activity converges to a ring, line, or point attractor during the delay period, and then rotates towards the output during the response period, preserving the attractor’s geometry.

This figure demonstrates the temporal dynamics of CordsNet compared to other CNN architectures. (A) shows an example of a feature map evolving over time in CordsNet-R8. (B) compares the neural activity and softmax output of different CNN architectures under various stimulus sequences, highlighting CordsNet’s ability to maintain accurate classifications across time. (C) and (D) illustrate CordsNet’s robustness to noise, showing its resilience in noisy image classification tasks compared to traditional CNNs.

More on tables

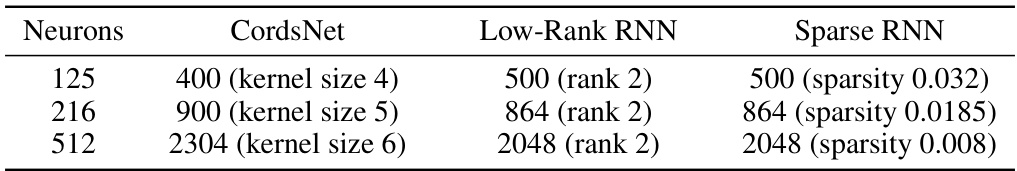

This table shows the number of trainable parameters in the recurrent weight matrices of different recurrent neural network architectures used in the paper’s experiments. Three different network sizes (125, 216, and 512 neurons) are compared. To keep the total number of parameters roughly consistent across the models, the kernel size of CordsNets, the rank of low-rank RNNs, and the sparsity of sparse RNNs were adjusted accordingly. This allows for a fair comparison of the different architectures’ performance in the subsequent cognitive tasks.

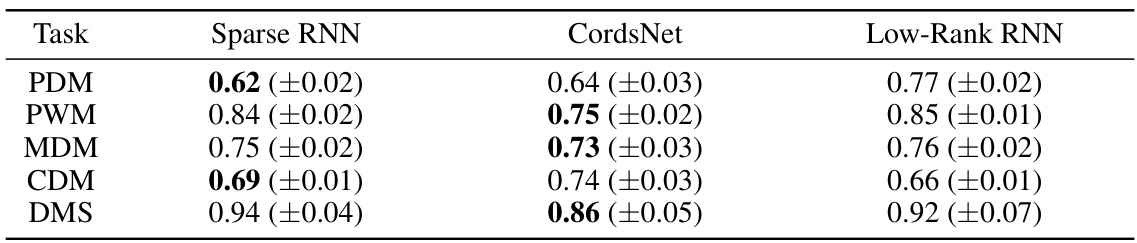

This table presents the mean Procrustes distances between the neural trajectories of different recurrent neural network architectures (Sparse RNN, CordsNet, Low-Rank RNN) and a fully-connected RNN across five cognitive tasks. Lower distances indicate greater similarity in the dynamical solutions found by the different architectures.

This table details the architecture of four different CordsNet models (CordsNet-R2, CordsNet-R4, CordsNet-R6, and CordsNet-R8) used for image classification. Each model consists of multiple blocks, each containing a convolutional layer (feedforward transformation) followed by a convolutional recurrent layer (recurrent weights). The table shows the output size of each block and the kernel sizes and number of channels for the convolutional and recurrent layers within each block. The final layer of each model consists of an average pooling layer, a linear layer, and a softmax layer for classification.

This table presents the test accuracies achieved by CordsNets using the proposed initialization method and after fine-tuning. It compares these results against their equivalent feedforward CNN counterparts. Control experiments involved training CordsNets directly (without the initialization method) and training fully-connected RNNs, both matched to the same training time as the initialization method. Results are shown for various datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet).

This table compares the test accuracies of CordsNets (trained using the proposed initialization method and fine-tuned) against their corresponding feedforward CNN counterparts across various datasets (MNIST, F-MNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100, and ImageNet). It also includes control experiments where CordsNets were trained directly without initialization and fully-connected RNNs were trained with matching parameter counts, providing a comprehensive comparison of the models’ performance.

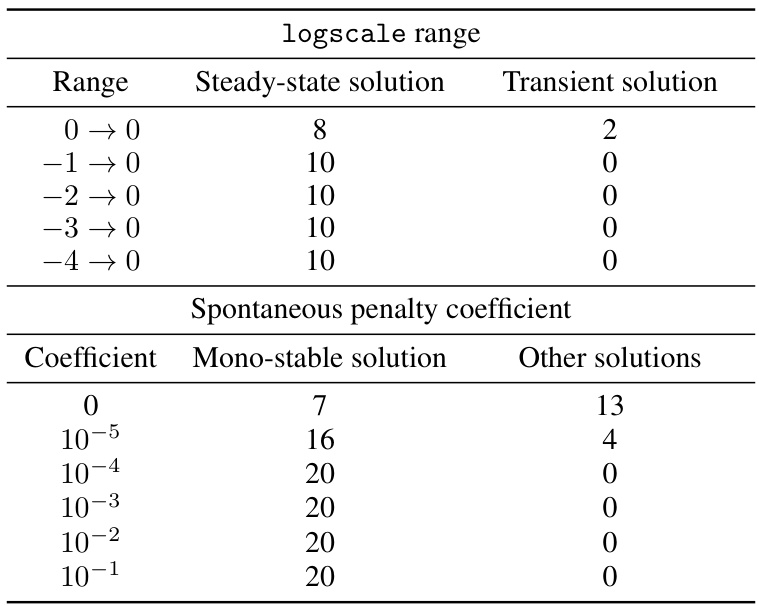

This ablation study investigates the impact of different ranges for the logarithmic scaling of cross-entropy loss across time steps and different coefficients for the spontaneous activity penalty term on the types of solutions obtained during training. The results indicate the number of models that converged to a steady-state solution versus a transient solution for varying logarithmic ranges and the number of models that converged to a mono-stable solution versus other solutions for varying spontaneous penalty coefficients. The goal was to identify parameter settings that reliably produce networks with mono-stable, consistent behavior.

Full paper#