↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Offline reinforcement learning (RL) faces challenges due to the distributional shift problem, which leads to overestimation errors in value functions. Existing penalized Q-learning methods, while effective in reducing overestimation, can introduce unnecessary underestimation bias.

This paper introduces Exclusively Penalized Q-learning (EPQ) to overcome this limitation. EPQ selectively penalizes only the states that are likely to cause overestimation errors, thus minimizing unnecessary bias. Experiments demonstrate that EPQ significantly reduces both overestimation and underestimation bias, leading to substantial performance gains in various offline control tasks compared to other offline RL algorithms. EPQ’s success is attributed to its ability to fine-tune penalty based on the data distribution and policy actions, offering a more effective approach to offline reinforcement learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in offline reinforcement learning as it directly addresses the prevalent issue of overestimation bias in existing methods, offering a novel solution with improved performance and reduced bias. It opens new avenues for research by proposing a selective penalization approach, paving the way for more effective and robust offline RL algorithms. This work is timely and relevant given the growing interest in offline RL for real-world applications, where continuous interaction with the environment is costly and risky.

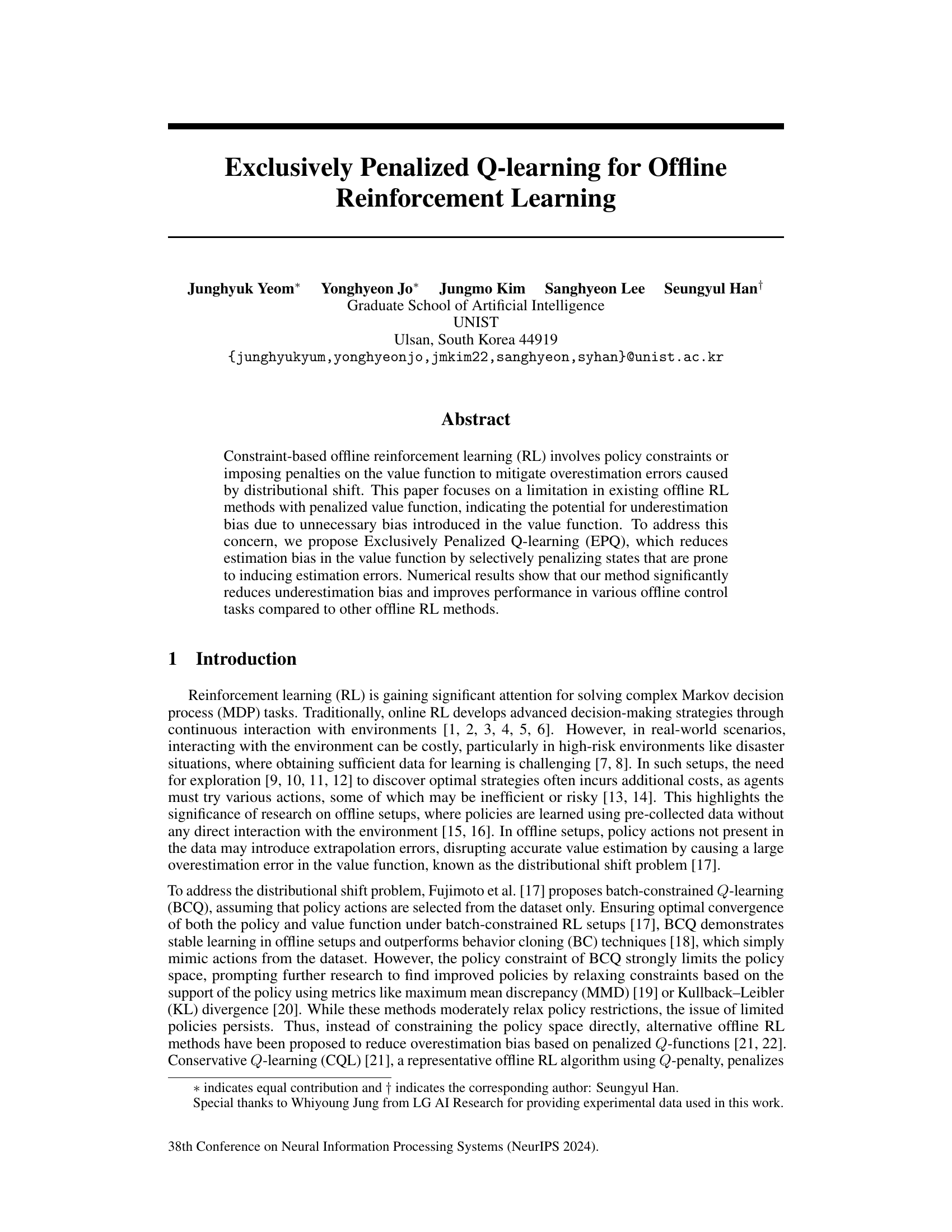

Visual Insights#

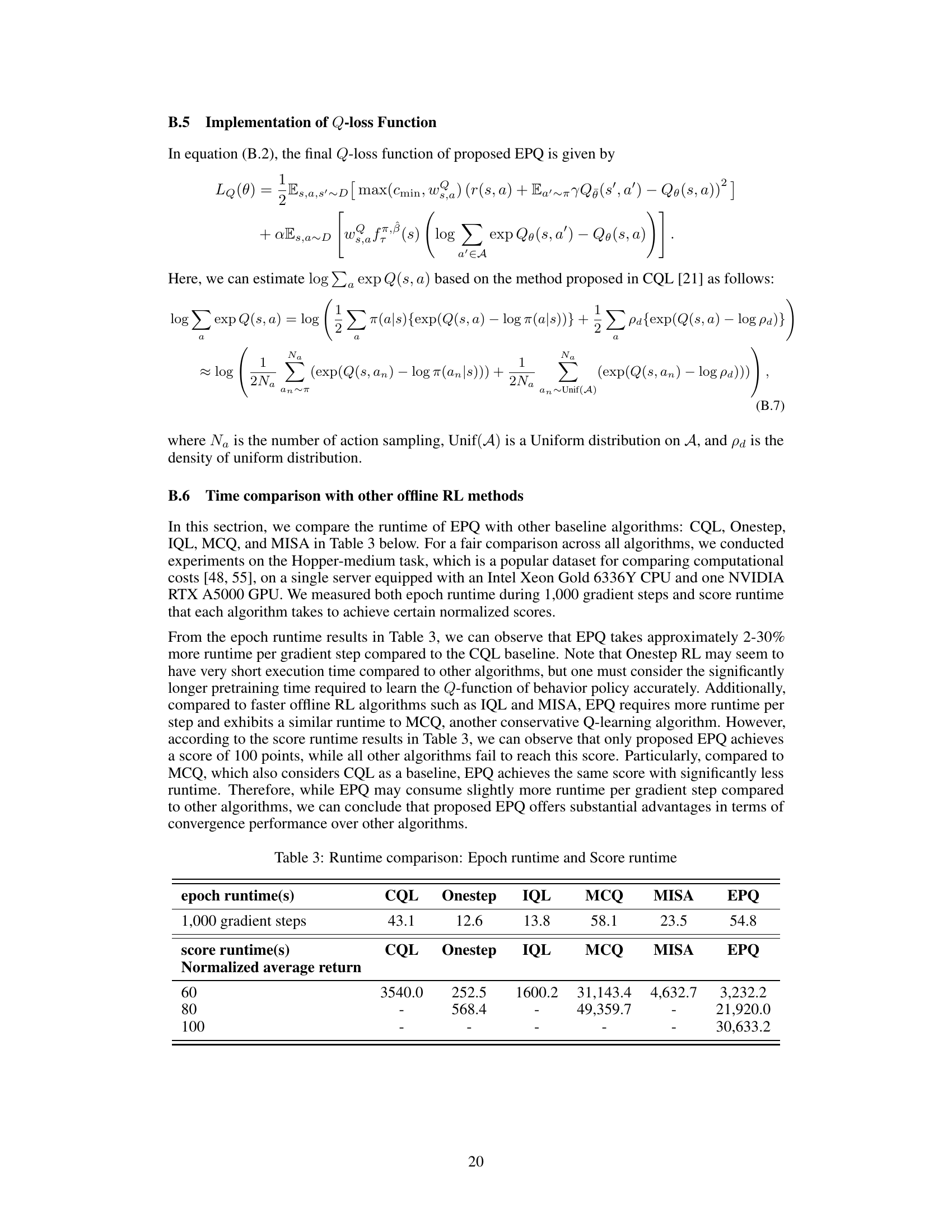

This figure demonstrates the effect of the penalization constant α in CQL on the estimation bias. Three scenarios are shown, each with different behavior policies (β) and target policies (π). The histograms show the distribution of actions for both policies. The plots show the estimation bias of CQL (average difference between the learned Q-function and the expected return) for different values of α. The figure highlights that CQL introduces unnecessary bias for states that do not contribute to overestimation.

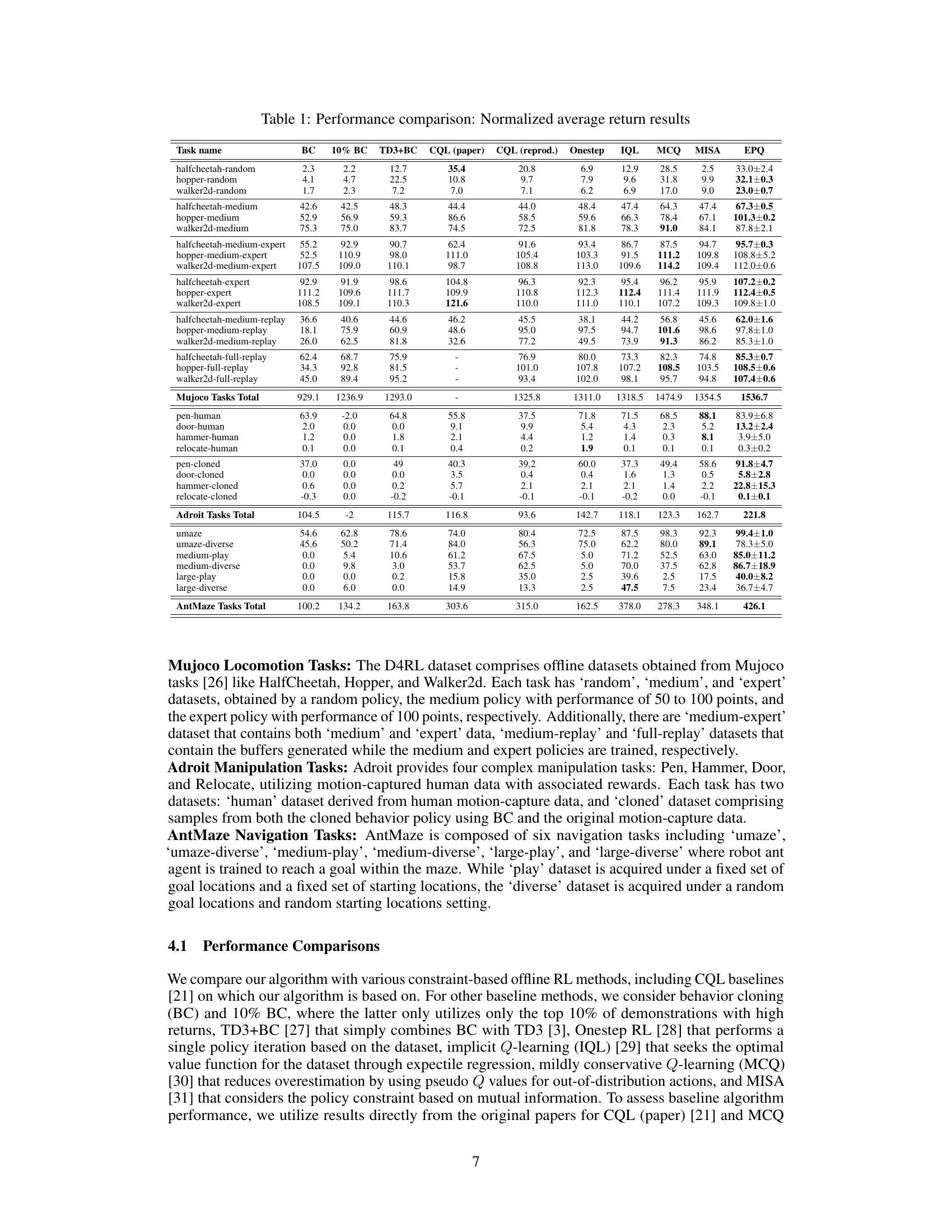

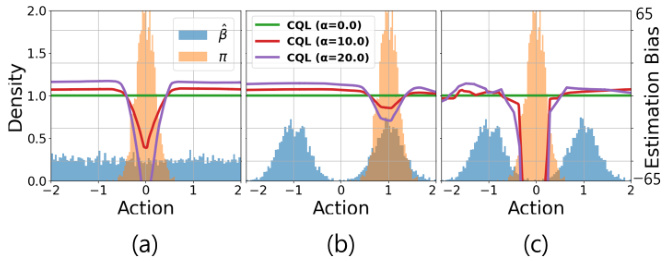

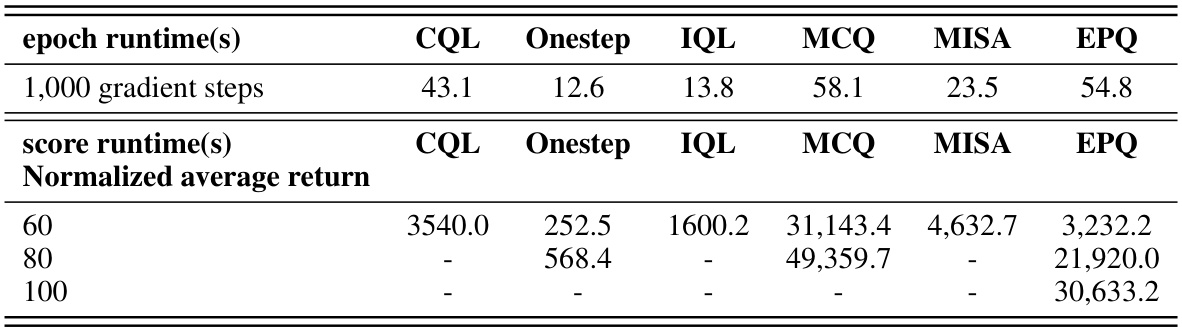

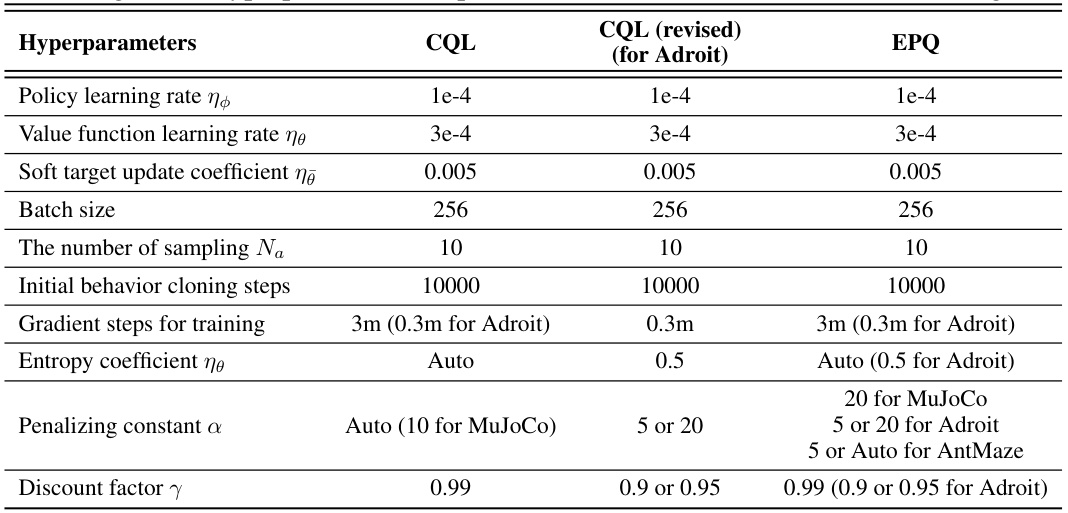

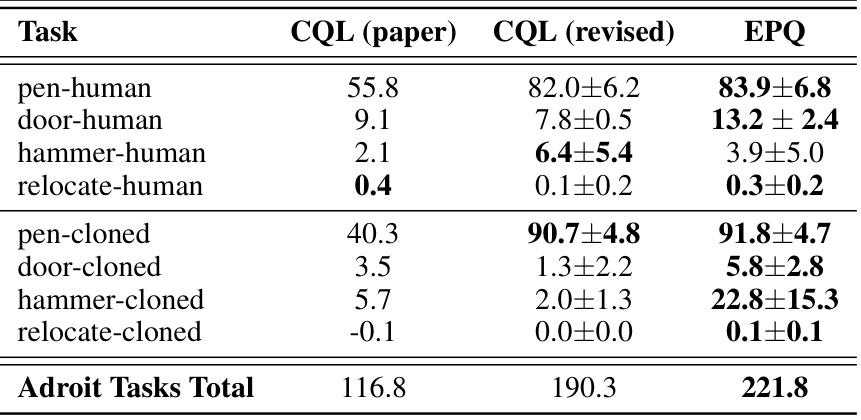

This table presents a comparison of the normalized average return results achieved by various offline reinforcement learning algorithms across different benchmark tasks. The algorithms include behavior cloning (BC), 10% BC, TD3+BC, CQL (paper), CQL (reprod.), Onestep, IQL, MCQ, MISA, and the proposed EPQ algorithm. The benchmark tasks are categorized into MuJoCo locomotion tasks, Adroit manipulation tasks, and AntMaze navigation tasks, each with multiple datasets representing varying levels of data quality and policy performance.

In-depth insights#

Offline RL Bias#

Offline reinforcement learning (RL) grapples with inherent biases stemming from the distributional shift between training data and the target policy’s behavior. Overestimation bias, a common problem, arises when the learned Q-function inaccurately assigns high values to actions unseen during training. This leads to overly optimistic policy evaluations and suboptimal performance. Conversely, underestimation bias can occur due to overly conservative penalty mechanisms that excessively penalize actions not explicitly present in the dataset, leading to risk-averse policies that underperform. Addressing these biases requires careful consideration of the data distribution and strategic mitigation techniques. Methods like conservative Q-learning aim to limit overestimation, but can inadvertently introduce underestimation. Therefore, developing sophisticated algorithms that selectively penalize only states prone to inducing errors and avoid unnecessary bias is crucial for robust offline RL.

EPQ Algorithm#

The Exclusively Penalized Q-learning (EPQ) algorithm is designed to address limitations in existing offline reinforcement learning methods that employ penalized value functions. EPQ selectively penalizes states prone to estimation errors, thereby mitigating overestimation bias without introducing unnecessary underestimation. This targeted approach improves the accuracy of the value function, leading to improved policy performance. A key innovation is its adaptive penalty mechanism, dynamically adjusting the penalty based on the dataset’s coverage of policy actions. This mitigates the over-penalization observed in methods like CQL, which can harm performance. The algorithm leverages a prioritized dataset for further enhancement, focusing the learning process on data points that significantly impact Q-value estimation. This prioritization, combined with the selective penalty scheme, enhances efficiency and robustness. Experimental results demonstrate EPQ’s superiority over various state-of-the-art offline reinforcement learning algorithms, particularly in complex tasks with sparse rewards.

Penalty Control#

Penalty control in offline reinforcement learning aims to mitigate the overestimation bias inherent in value function approximation. Careful penalty application is crucial because excessive penalties can introduce underestimation bias, hindering performance. The effectiveness of penalty methods hinges on selectively penalizing states prone to errors, avoiding unnecessary bias in states where accurate estimation is possible. A key challenge lies in determining the optimal penalty strength. Too little penalty may not effectively curb overestimation, while too much can lead to underestimation. Adaptive penalty mechanisms, adjusting penalties based on data distribution and policy behavior, offer a promising approach to balance these competing concerns. Threshold-based penalties or penalty adaptation factors are used to selectively apply penalties, improving efficiency and reducing unwanted bias. The impact of penalty control on the overall offline learning process and its effect on the convergence rate is a key aspect requiring further investigation. Successfully balancing penalty application for optimal performance is paramount for practical offline reinforcement learning.

Prioritized Data#

Utilizing prioritized data in offline reinforcement learning (RL) addresses the challenge of distributional shift by focusing the learning process on the most informative data points. This involves weighting samples based on their relevance to policy improvement, often by prioritizing those with higher Q-values, or those that are more likely to reduce uncertainty about the value function. Prioritization can significantly improve efficiency by reducing the impact of out-of-distribution data, which can lead to overestimation errors. However, careful consideration must be given to how prioritization is implemented to avoid introducing bias or harming performance. An effective prioritization strategy should balance maximizing informative samples while minimizing the risk of inadvertently focusing on irrelevant data or overfitting to the behavior policy. It’s a crucial aspect of effective offline RL that requires careful design and evaluation.

Future Works#

Future work could explore several promising avenues. Extending EPQ to handle continuous action spaces more effectively is crucial, as many real-world problems involve continuous controls. The current threshold-based penalty might require adaptation for such scenarios. Another important direction is improving the efficiency of the prioritized dataset. The computational cost of generating and updating ßexp(Q) can be significant, limiting scalability. Investigating alternative methods for prioritizing data or reducing the computational burden could enhance the algorithm’s practical applicability. A thorough empirical comparison across a broader range of offline RL benchmarks is warranted. While the paper presents results on D4RL, additional experiments on other datasets could provide a more comprehensive evaluation and reveal potential limitations or strengths of EPQ in diverse settings. Finally, theoretical analysis to provide stronger guarantees on convergence and performance would be valuable. The current theoretical results focus on underestimation bias, but a more complete analysis addressing overestimation and overall performance bounds is needed.

More visual insights#

More on figures

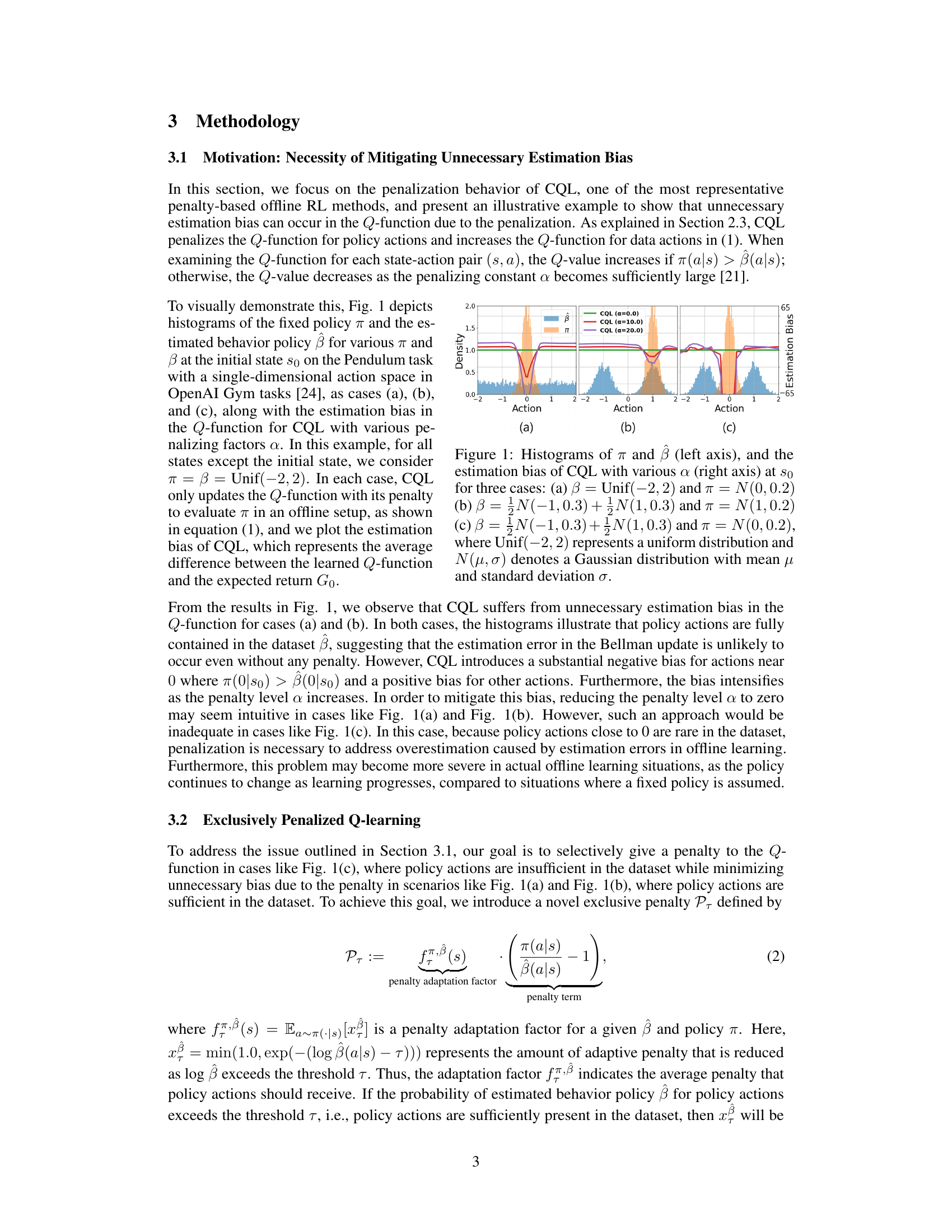

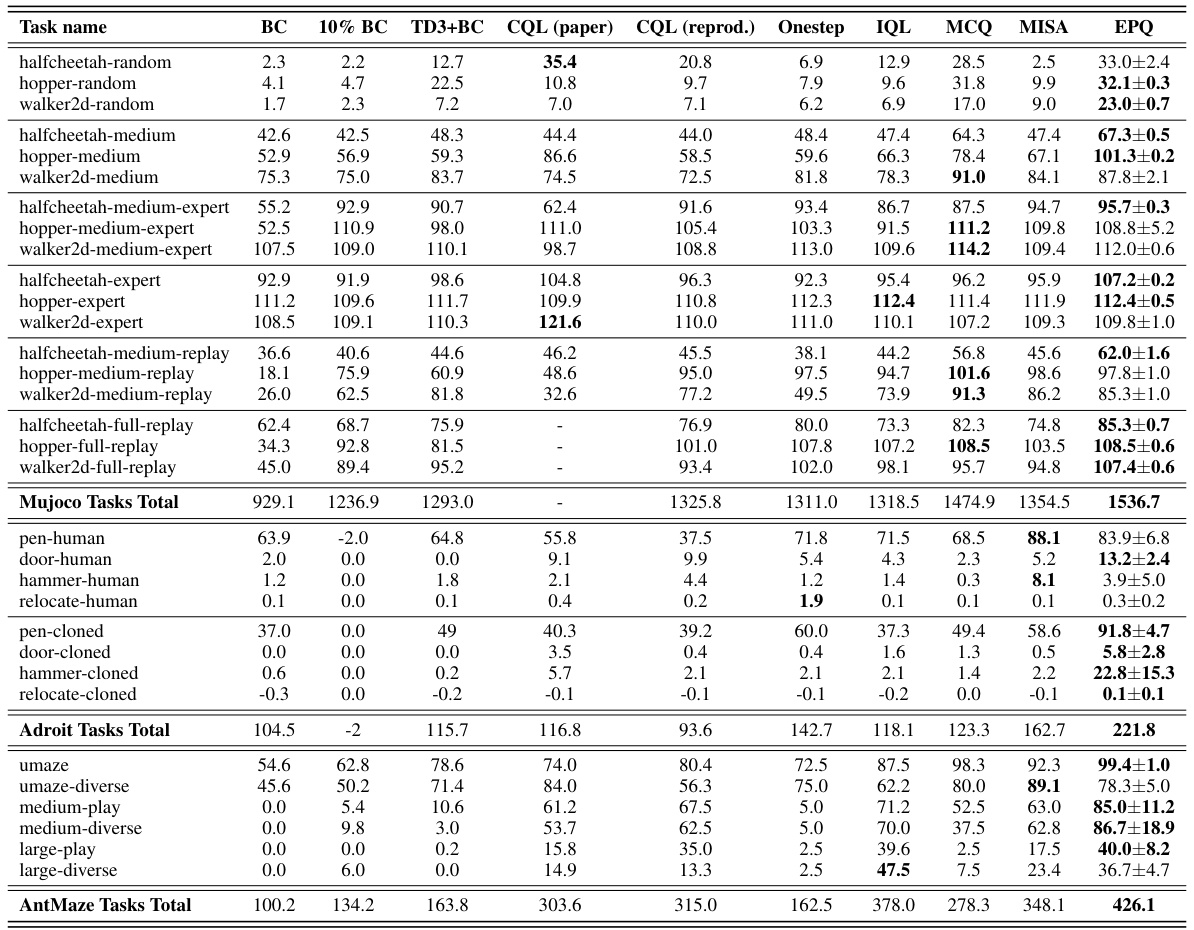

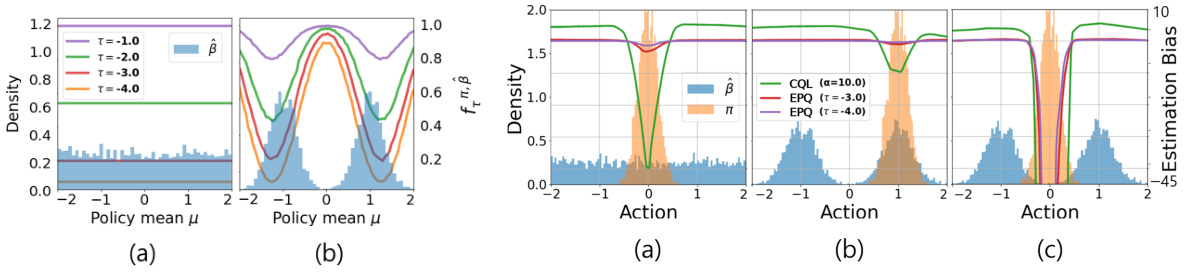

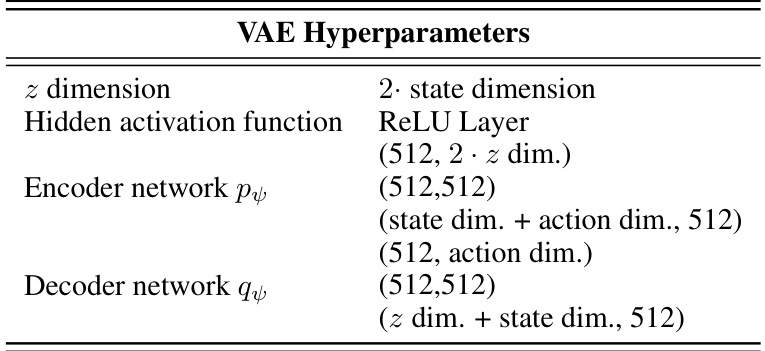

This figure illustrates the exclusive penalty used in the EPQ algorithm. Panel (a) shows how the log-probability of the behavior policy β changes with the number of data samples (N) and how the thresholds (τ) for the penalty adaptation are adjusted accordingly. Panel (b) shows how the penalty adaptation factor (fπ,β) is calculated based on the difference between the log-probability of β and the thresholds τ, resulting in different penalty amounts for different policies (π). The goal is to selectively penalize only when policy actions are insufficient in the dataset, minimizing unnecessary bias.

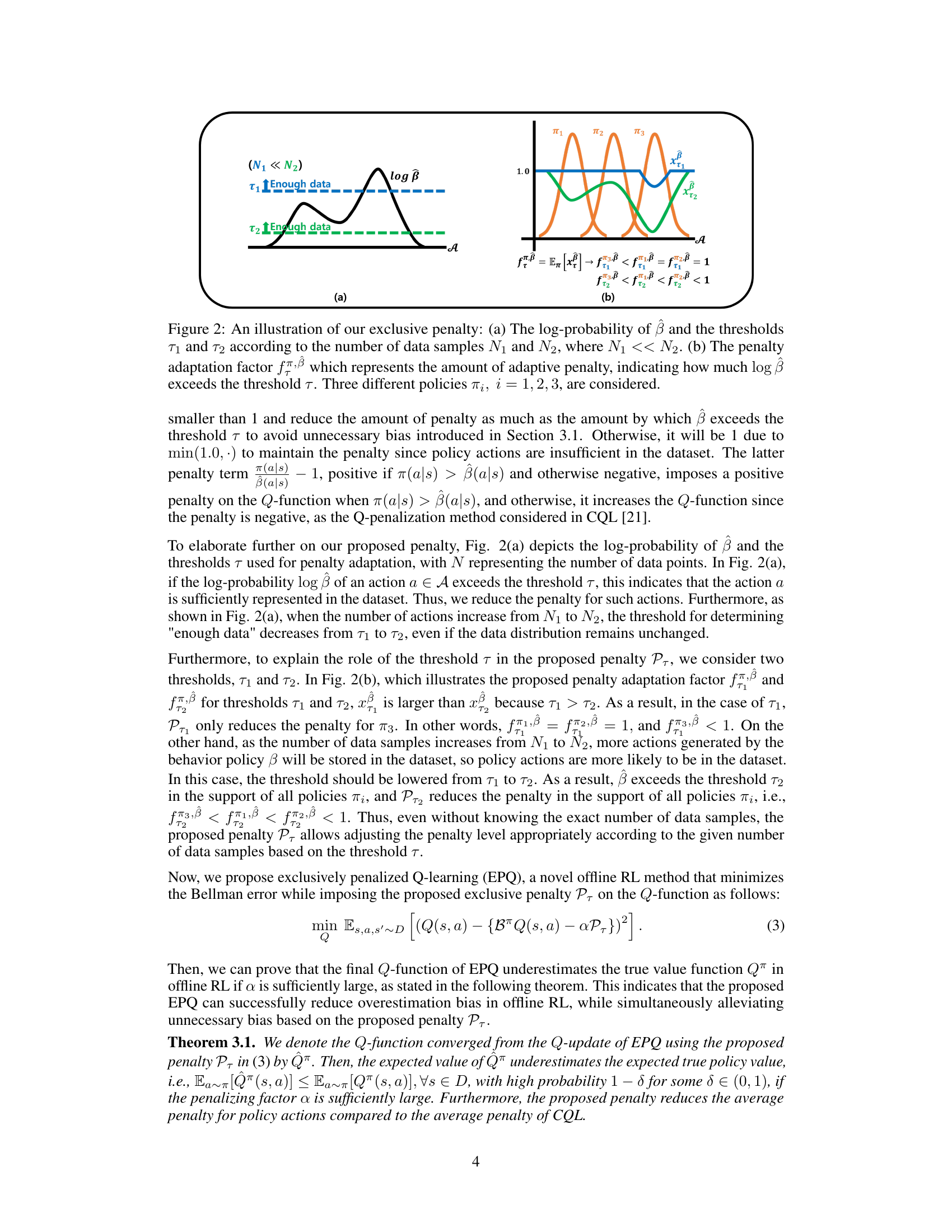

This figure visualizes the penalty adaptation factor fπ,β(s) for different policy distributions (π) and behavior policies (β). Two scenarios are shown: (a) a uniform behavior policy and (b) a bimodal Gaussian behavior policy. The histograms display the distribution of actions (β) and how the penalty adaptation factor varies with threshold τ for different policy distributions. The penalty factor fπ,β(s) decreases as the log-probability of the behavior policy exceeds the threshold τ, reflecting the intention to reduce penalties when the policy actions have sufficient support in the dataset.

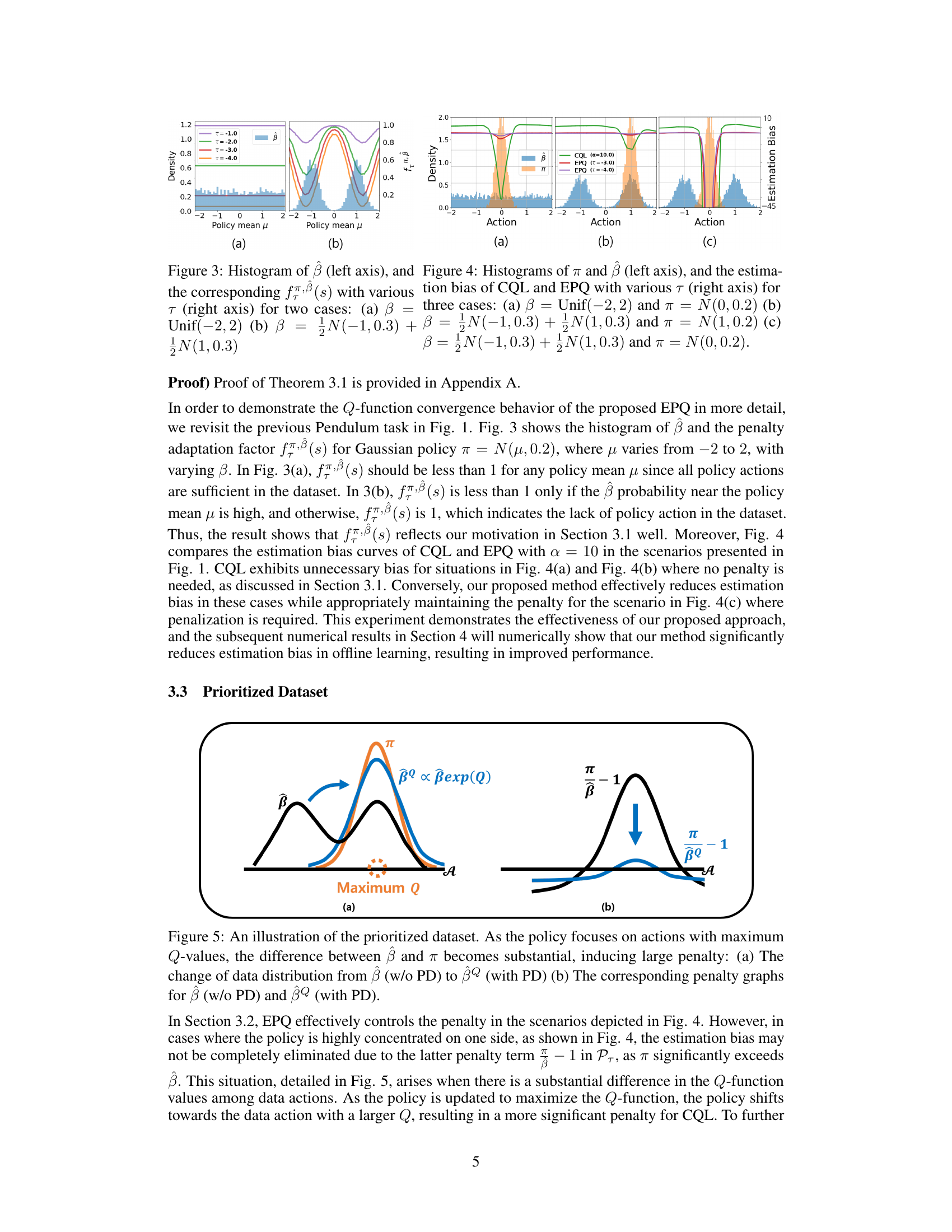

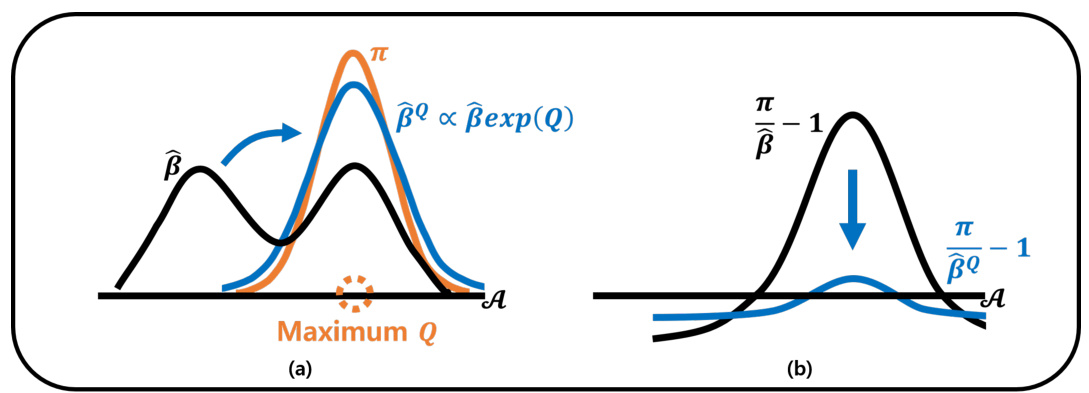

This figure illustrates how the prioritized dataset (PD) addresses the issue of large penalties arising when the policy π concentrates on actions with maximum Q-values, particularly when these actions are not sufficiently present in the original dataset β. Panel (a) shows how the PD, denoted as βº, modifies the data distribution β by emphasizing actions with high Q-values. Panel (b) shows that this modification significantly reduces the penalty associated with the policy π when compared to using the unmodified dataset β.

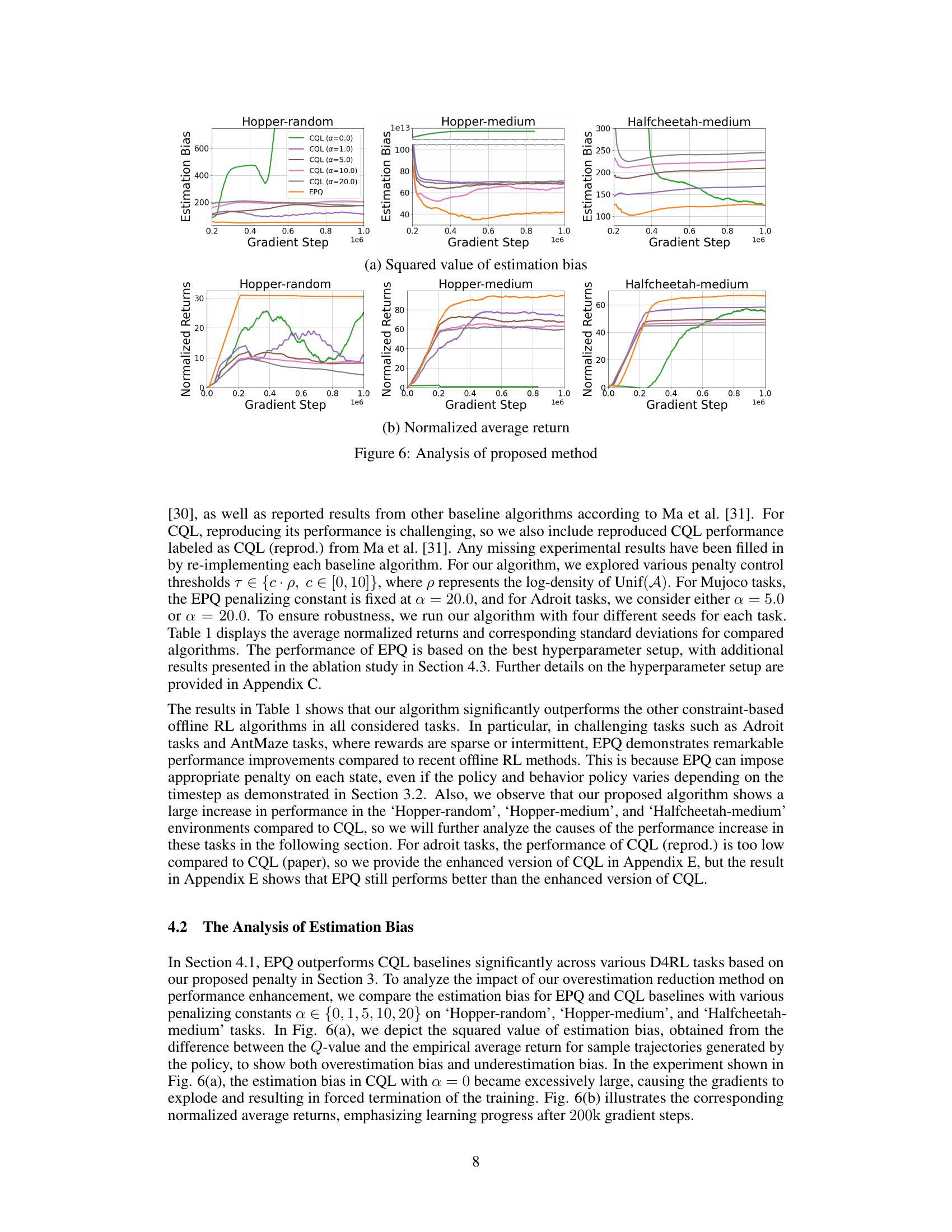

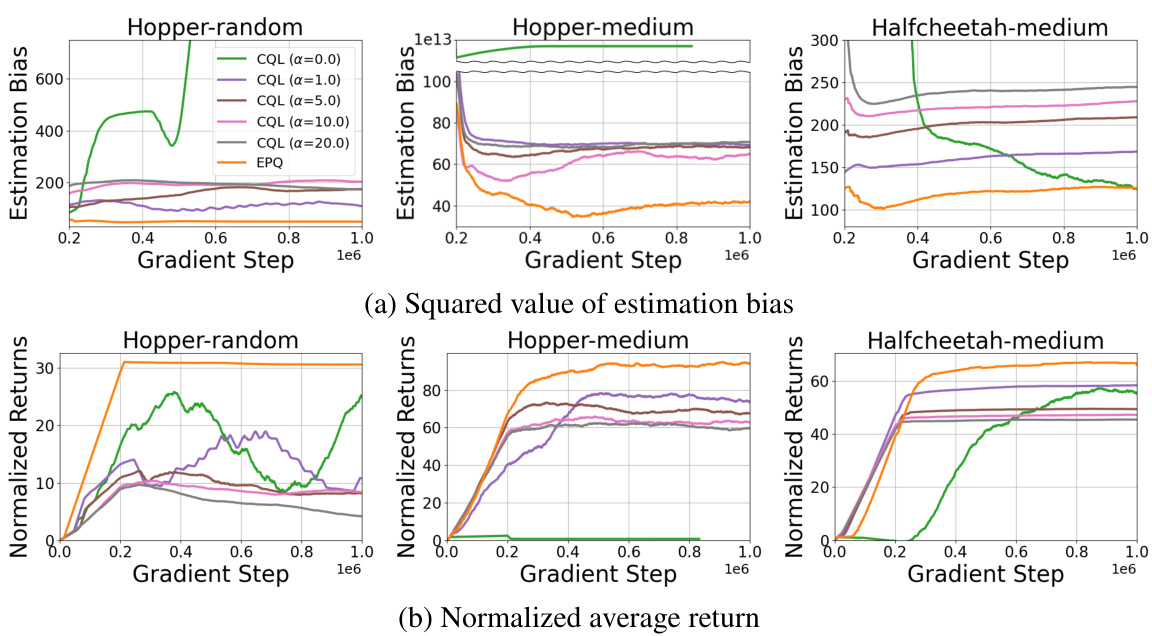

This figure shows the analysis of the proposed method, EPQ, compared to CQL. The top row (a) presents the squared value of the estimation bias for both methods across different gradient steps in three Mujoco tasks (Hopper-random, Hopper-medium, and Halfcheetah-medium). The bottom row (b) displays the normalized average return achieved in the same tasks under similar conditions. The plots illustrate that EPQ effectively reduces the estimation bias (both overestimation and underestimation) and improves the normalized average returns compared to CQL, especially in the Hopper and Halfcheetah tasks.

This figure presents a comparison of the proposed EPQ method with CQL across different Mujoco tasks. It shows plots of both squared estimation bias and normalized average return, demonstrating that EPQ significantly reduces unnecessary estimation bias compared to CQL, leading to improved performance.

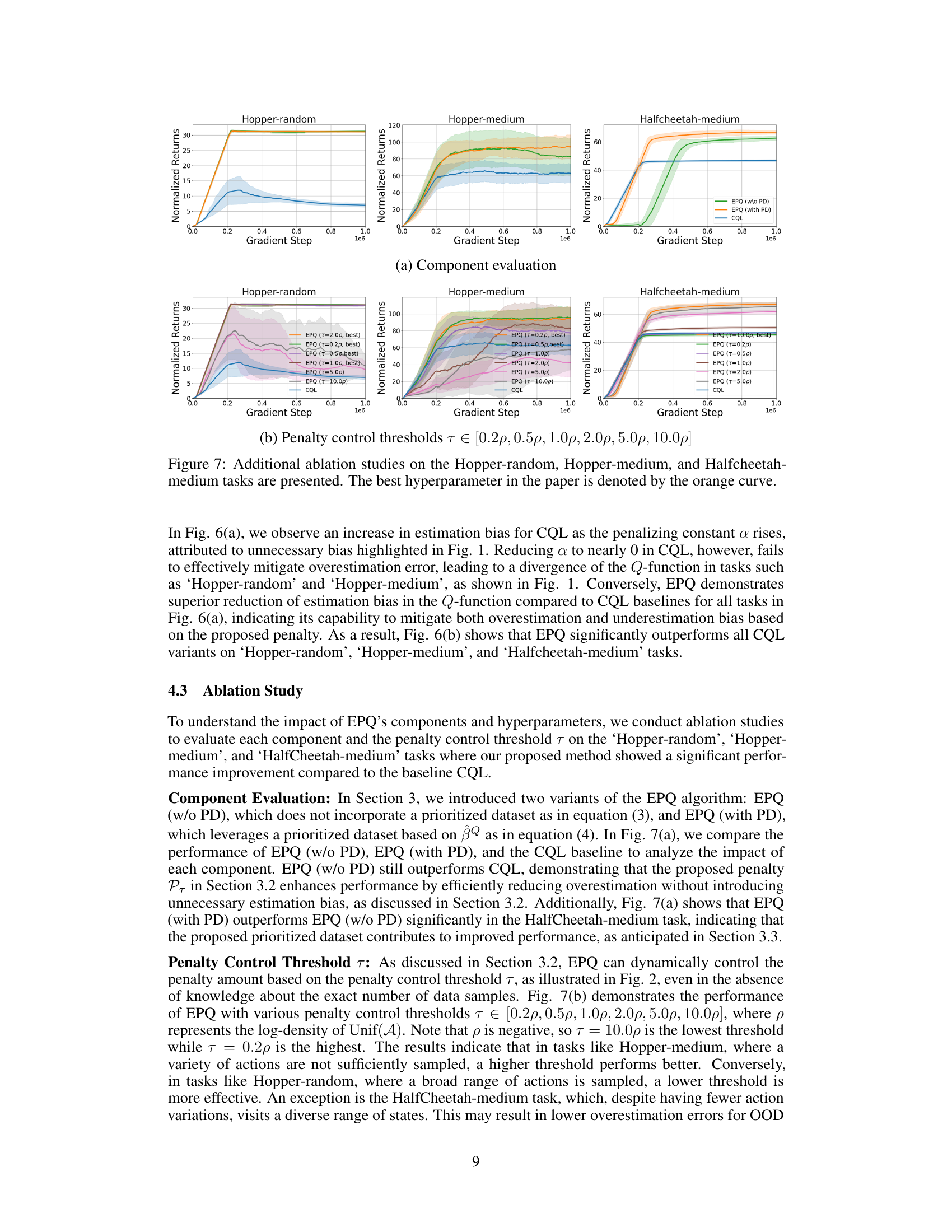

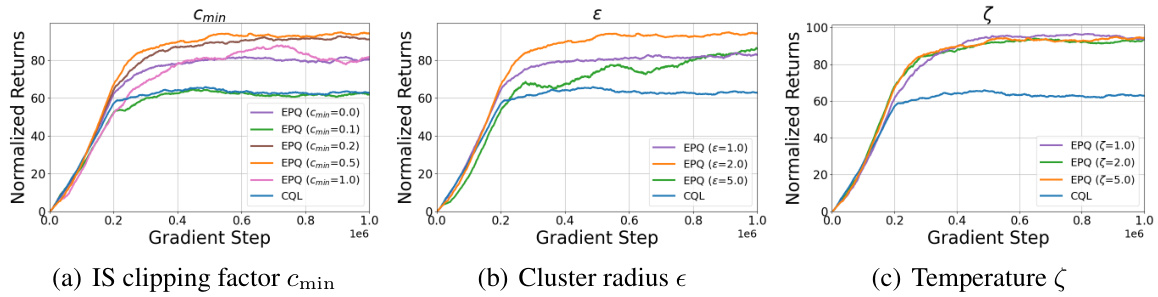

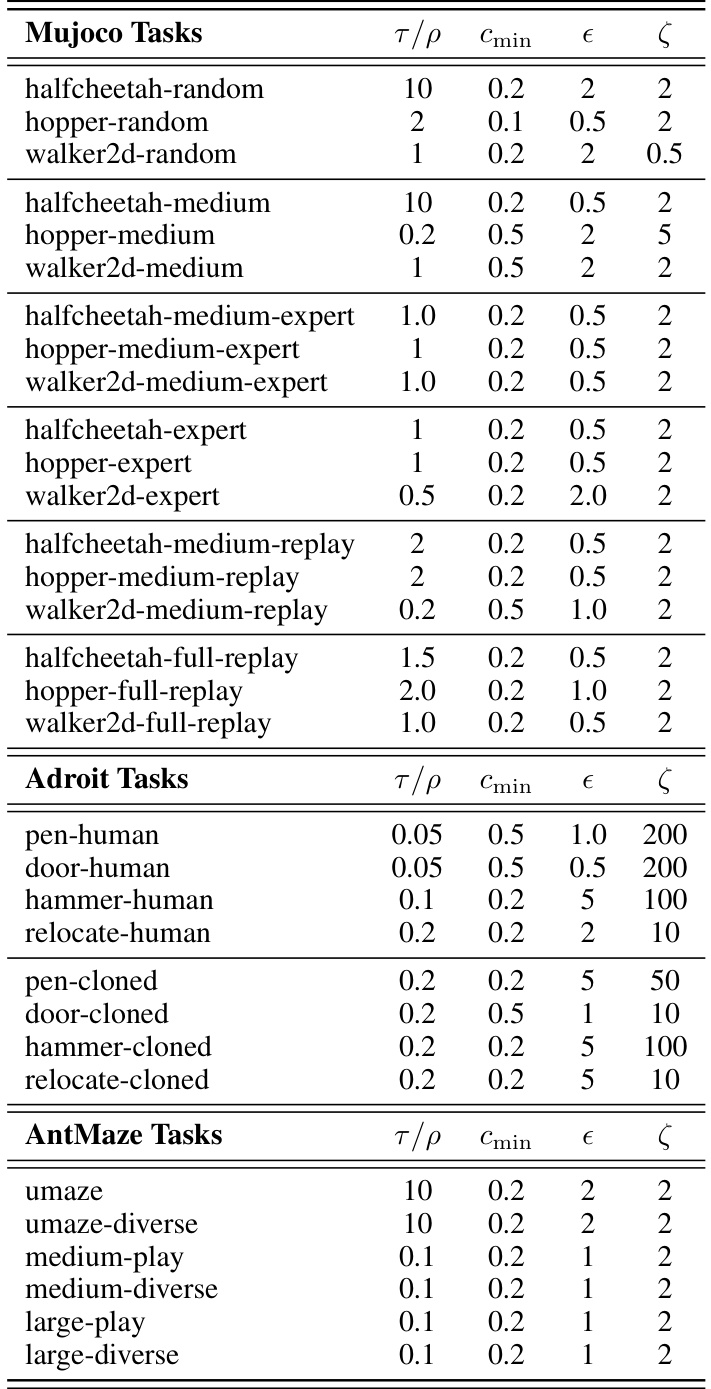

This figure presents additional ablation studies on the Hopper-medium task focusing on the impact of three hyperparameters related to the importance sampling (IS) weight calculation in the EPQ algorithm: the IS clipping factor (Cmin), the cluster radius (ε), and the temperature (ζ). Each subplot shows the normalized average return over gradient steps for various settings of the corresponding hyperparameter, along with the results for the CQL baseline. The goal is to analyze how these parameters affect the performance of EPQ.

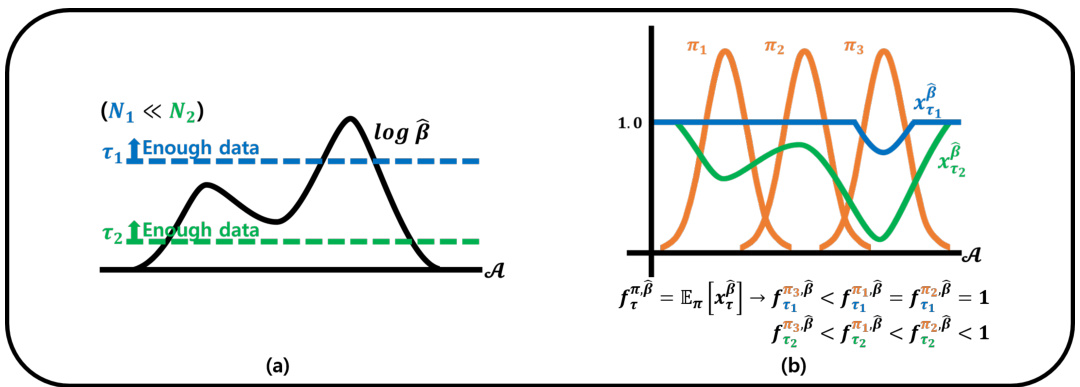

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of the normalized average return achieved by different offline reinforcement learning algorithms across various tasks from the D4RL benchmark. The algorithms compared include Behavior Cloning (BC), 10% BC, TD3+BC, CQL (paper), CQL (reproduced), Onestep, IQL, MCQ, MISA, and the proposed EPQ method. The tasks cover MuJoCo locomotion, Adroit manipulation, and AntMaze navigation, each with multiple datasets representing varying levels of data quality and policy behavior.

This table presents a comparison of the average return achieved by different offline reinforcement learning algorithms across various benchmark tasks. The results are normalized between 0 and 100, with 0 representing random performance and 100 representing expert performance. The algorithms compared include behavior cloning (BC), 10% BC, TD3+BC, CQL (from the original paper and a reproduction), Onestep, IQL, MCQ, MISA, and the proposed EPQ. The tasks are categorized into MuJoCo locomotion tasks, Adroit manipulation tasks, and AntMaze navigation tasks, each with multiple datasets representing varying data quality and policy characteristics. The table allows for a comprehensive comparison of the performance of different methods in offline RL.

This table compares the performance of EPQ with other state-of-the-art offline reinforcement learning algorithms across various tasks from the D4RL benchmark. The tasks are categorized into Mujoco locomotion tasks, Adroit manipulation tasks, and AntMaze navigation tasks. Each task includes several datasets representing different levels of difficulty and data collection methods (random, medium, expert, replay). The table shows the normalized average return for each algorithm and dataset, providing a quantitative assessment of relative performance.

This table presents a comparison of the average return achieved by different offline reinforcement learning algorithms across various tasks from the D4RL benchmark. The results are normalized between 0 and 100, where 0 represents random performance and 100 represents expert performance. The algorithms compared include behavior cloning (BC), 10% BC, TD3+BC, CQL (paper), CQL (reprod.), Onestep, IQL, MCQ, MISA, and the proposed EPQ method. The tasks are categorized into Mujoco locomotion tasks, Adroit manipulation tasks, and AntMaze navigation tasks, each with multiple datasets representing different data distributions (e.g., random, medium, expert).

This table compares the performance of the proposed EPQ algorithm against several existing offline reinforcement learning algorithms across various tasks from the D4RL benchmark. The tasks are categorized into Mujoco Locomotion, Adroit Manipulation, and AntMaze Navigation tasks, with different dataset variations for each. The results show normalized average returns (0-100 scale), providing a clear comparison of the algorithms’ performance in different scenarios.

Full paper#