↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Efficient arithmetic units are critical for fast and compact hardware. Existing methods for designing adders and multipliers often fail to sufficiently optimize both speed and size. This leads to increased latency and larger modules, hindering overall system performance. This research addresses this limitation by casting the design task as a tree generation game, leveraging reinforcement learning to find superior designs.

This paper introduces ArithTreeRL, a novel method for designing adders and multipliers using reinforcement learning. The key innovation is representing the design problem as a game, which allows the system to efficiently explore the vast design space. ArithTreeRL demonstrates significant improvements over existing techniques in both speed and size for both adders and multipliers. The results indicate that the approach is not only effective but also scalable, applicable to state-of-the-art 7nm technology.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for hardware designers seeking to improve the performance and efficiency of arithmetic units. By introducing novel tree generation methodologies and leveraging reinforcement learning, this research provides a significant step towards optimizing adder and multiplier designs in modern hardware architectures, particularly relevant in resource-constrained environments and high-performance computing domains.

Visual Insights#

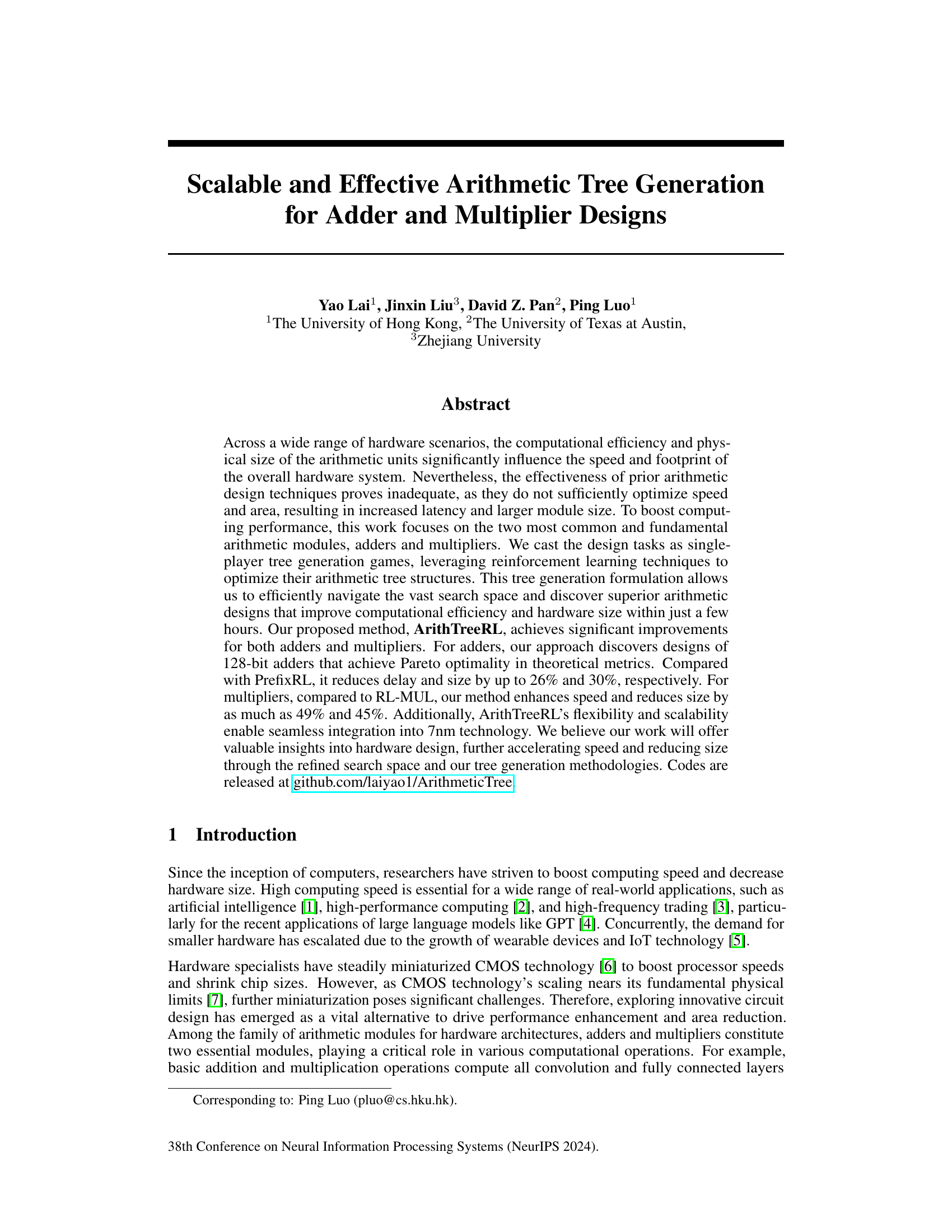

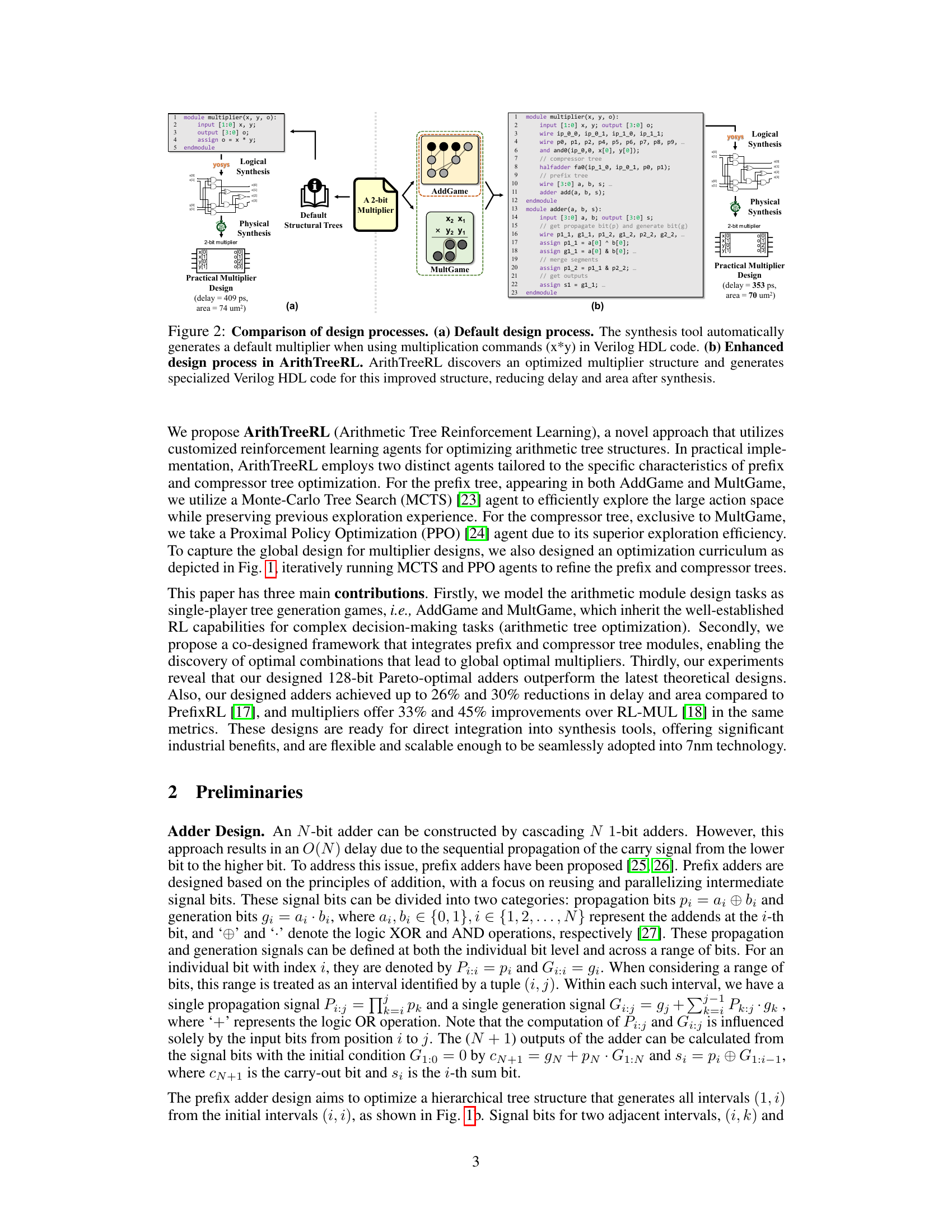

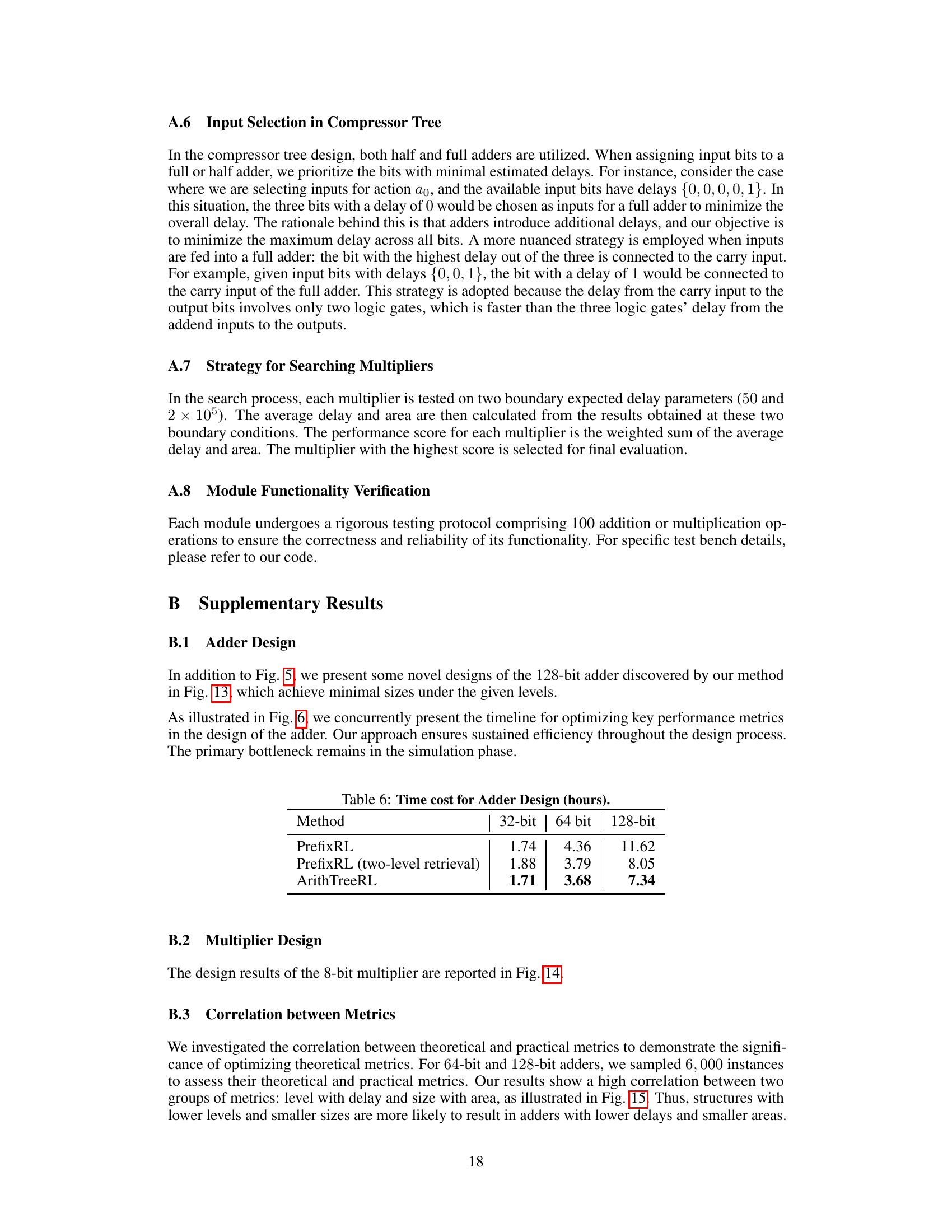

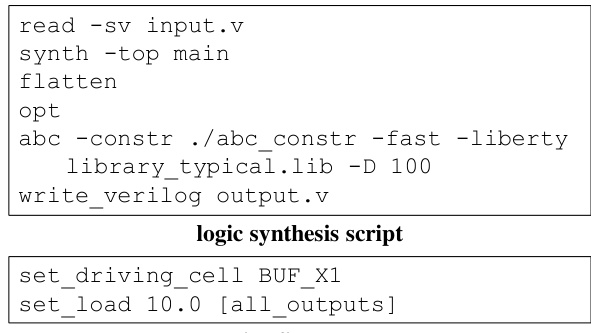

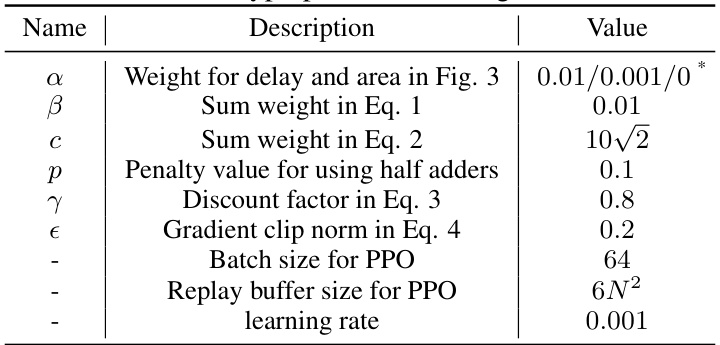

This figure illustrates the ArithTreeRL framework and different tree structures used for adder and multiplier designs. (a) shows the overall framework where two reinforcement learning agents optimize prefix and compressor trees separately. (b) shows the structure of a prefix tree used in adder design, illustrating how different configurations can affect the final adder design. (c) shows the structure of a compressor tree used in multiplier design, again highlighting how different configurations lead to varying outcomes. The different tree structures are directly related to the efficiency and area of the final adder or multiplier designs.

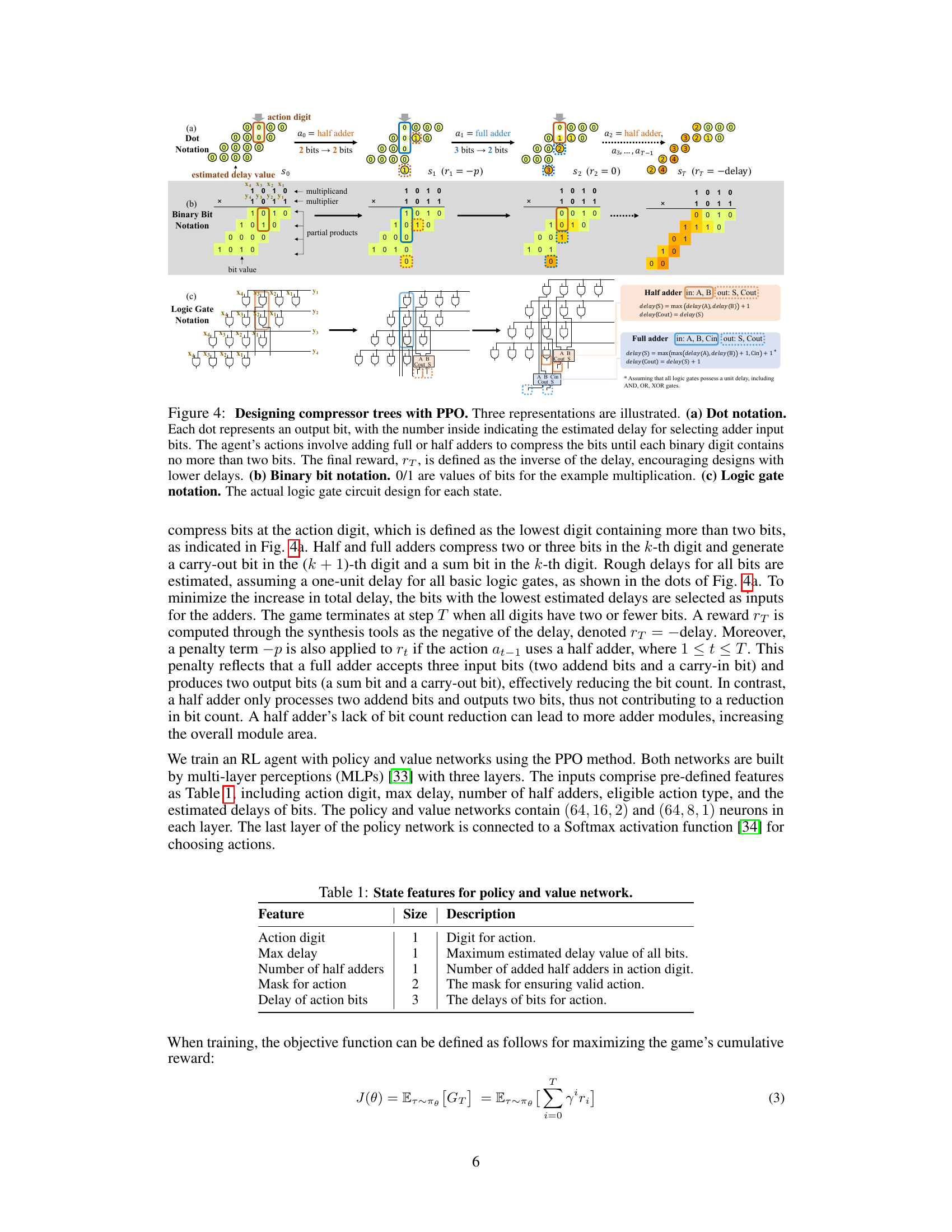

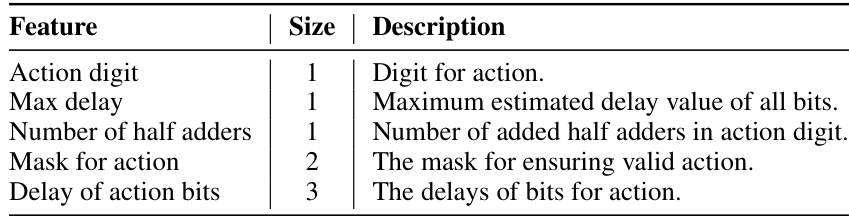

This table lists the features used as input to both the policy and value networks in the MultGame. Each feature represents a different aspect of the state of the game, aiding the reinforcement learning agent in making decisions about which actions to take (adding a half or full adder). The ‘Size’ column indicates the dimensionality of each feature.

In-depth insights#

ArithTreeRL Framework#

The ArithTreeRL framework represents a novel approach to designing efficient arithmetic circuits by casting the design problem as a tree generation game. Reinforcement learning agents are employed to optimize the structures of both prefix and compressor trees, crucial components in adders and multipliers, respectively. The framework leverages the power of game theory, enabling efficient exploration of the vast design space. AddGame focuses on prefix tree optimization in adders, while MultGame jointly optimizes both compressor and prefix trees in multipliers. This co-design approach is key to achieving global optimality. The framework’s flexibility allows seamless integration into existing design flows, promising significant improvements in both computational efficiency and hardware size. MCTS and PPO algorithms are intelligently used to handle the complexity of the search space. The framework ultimately delivers a powerful methodology for accelerating the design process and achieving optimal arithmetic circuits.

RL Agents & Curriculum#

Reinforcement learning (RL) agents are crucial for navigating the complex search space of arithmetic tree optimization. The paper employs two distinct agents: a Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) agent for prefix tree optimization and a Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) agent for compressor tree optimization, leveraging the strengths of each algorithm. MCTS excels in exploring large action spaces while retaining previous experience, making it suitable for the prefix tree. PPO’s superior exploration efficiency is better suited for the compressor tree, which requires a more flexible approach. A key insight is the implementation of an optimization curriculum, iteratively refining the prefix and compressor trees. This curriculum leverages the complementary strengths of the two agents to achieve globally optimal designs. This combined approach, along with novel hardware design methodologies, leads to significant improvements in both speed and area compared to existing state-of-the-art methods.

Adder/Multiplier Games#

The conceptualization of adder and multiplier design as games is a novel approach that leverages the power of reinforcement learning. By framing the design process as interactive games, the authors effectively transform a complex optimization problem into a series of manageable decisions. AddGame and MultGame specifically target adders and multipliers, respectively, allowing for tailored optimization strategies. The use of reinforcement learning agents, such as MCTS and PPO, enables efficient exploration of the vast design space. This game-based approach offers a flexible and scalable solution, allowing for seamless integration into various hardware designs and facilitating superior designs in terms of speed and area.

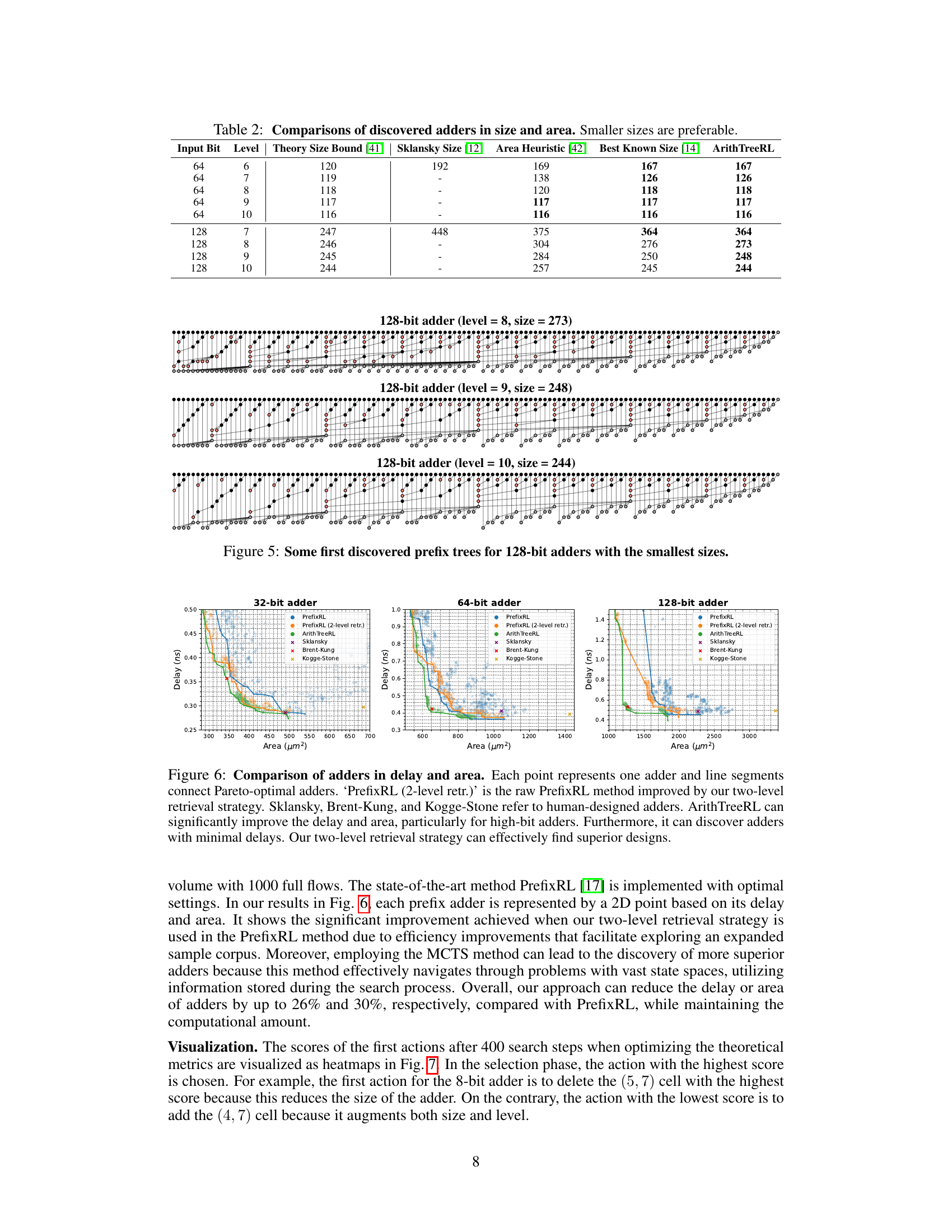

Pareto-Optimal Adders#

The concept of “Pareto-optimal adders” points towards a crucial design challenge in computer arithmetic: finding adder designs that offer the best possible combination of speed and size. A Pareto-optimal solution represents a design where any improvement in one metric (e.g., speed) necessitates a compromise in the other (e.g., size). This means there’s no single “best” adder; the optimal design depends on the specific priorities of the application. Research on Pareto-optimal adders often involves sophisticated optimization techniques, such as integer linear programming or reinforcement learning, to explore the vast design space and discover superior adder configurations that are both fast and compact. The exploration of Pareto-optimal adders is essential as modern hardware systems often rely on extremely efficient arithmetic units, and improving adder design is key to building faster and smaller devices.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore extending ArithTreeRL to encompass a broader range of arithmetic modules, beyond adders and multipliers. This might involve tackling more complex operations like division and square root calculation, or exploring specialized arithmetic units for specific applications (e.g., digital signal processing). Another promising area is investigating the use of more advanced RL algorithms or hybrid approaches to further enhance the efficiency and scalability of the tree generation process. For instance, incorporating techniques like evolutionary algorithms or multi-agent RL could potentially lead to superior designs. The work could also focus on improving the synthesis and integration flows, reducing the reliance on external tools and potentially developing a more streamlined, integrated design methodology. Finally, a critical future step would be a thorough experimental validation of ArithTreeRL across a wider range of technologies and fabrication processes, beyond the 7nm technology explored in this paper, to demonstrate its broader applicability and robustness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

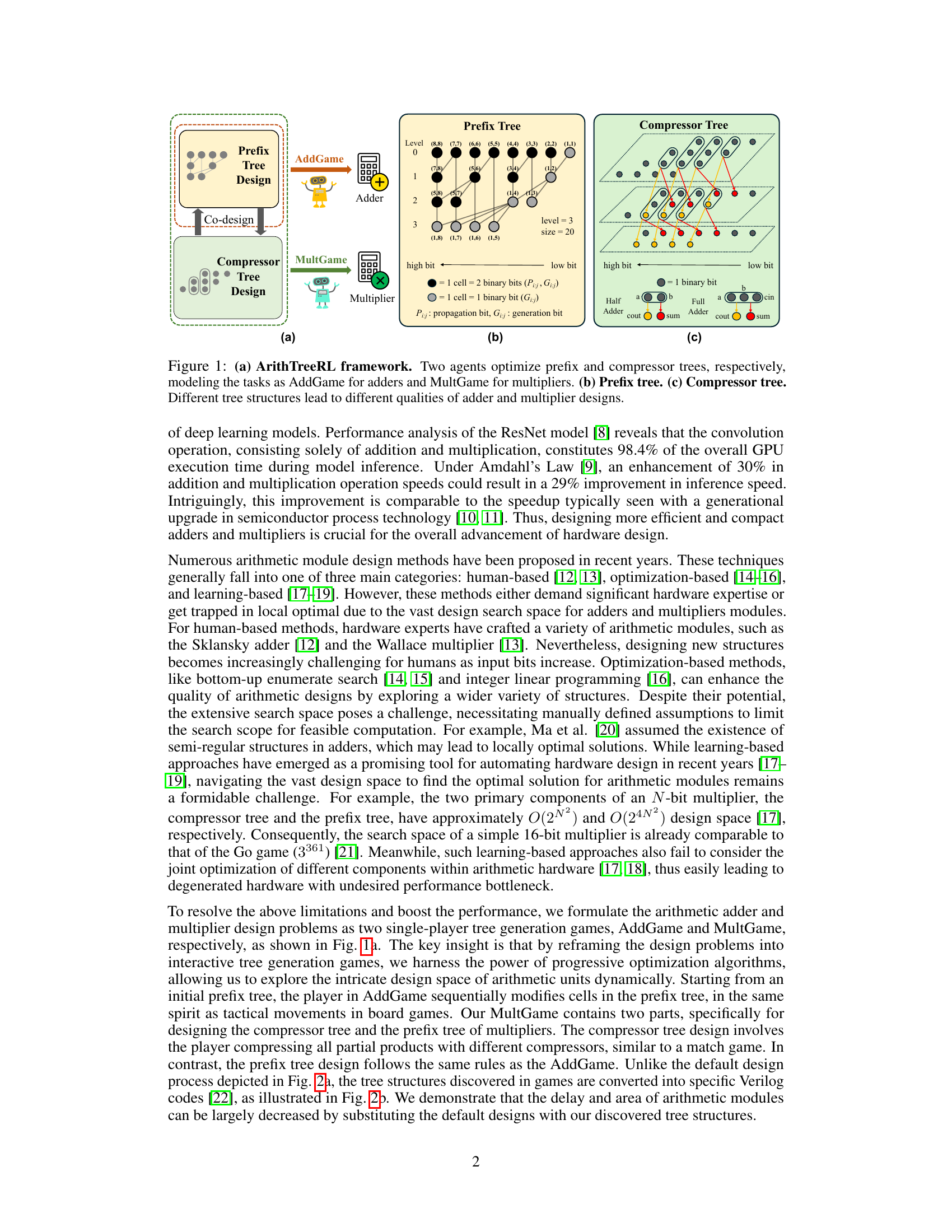

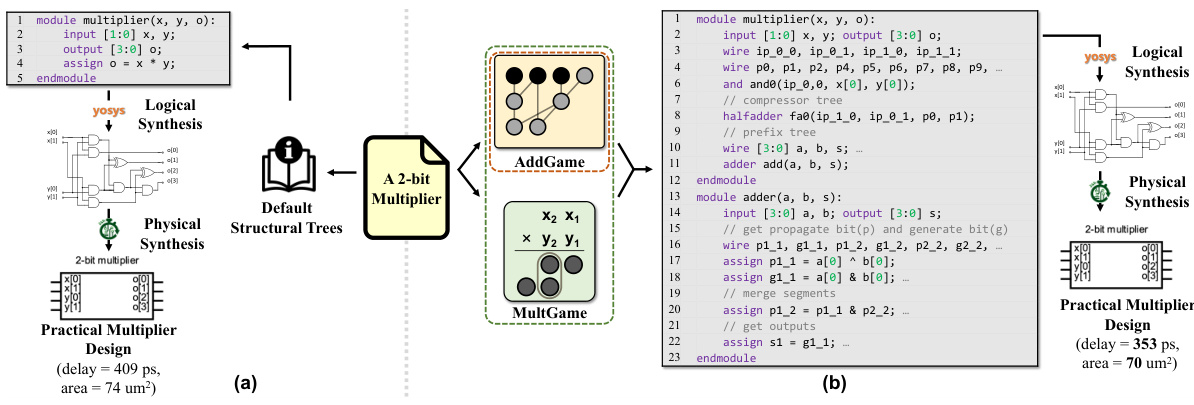

This figure compares two design processes for multipliers: the default process using a synthesis tool and the enhanced process using ArithTreeRL. The default process directly generates a multiplier from Verilog code, resulting in a design with higher delay and area. ArithTreeRL enhances this process by discovering an optimized multiplier structure, generating specialized Verilog code for that structure, which results in a significant reduction in both delay and area after the synthesis process. It demonstrates the impact of ArithTreeRL’s optimized tree structure in improving hardware efficiency.

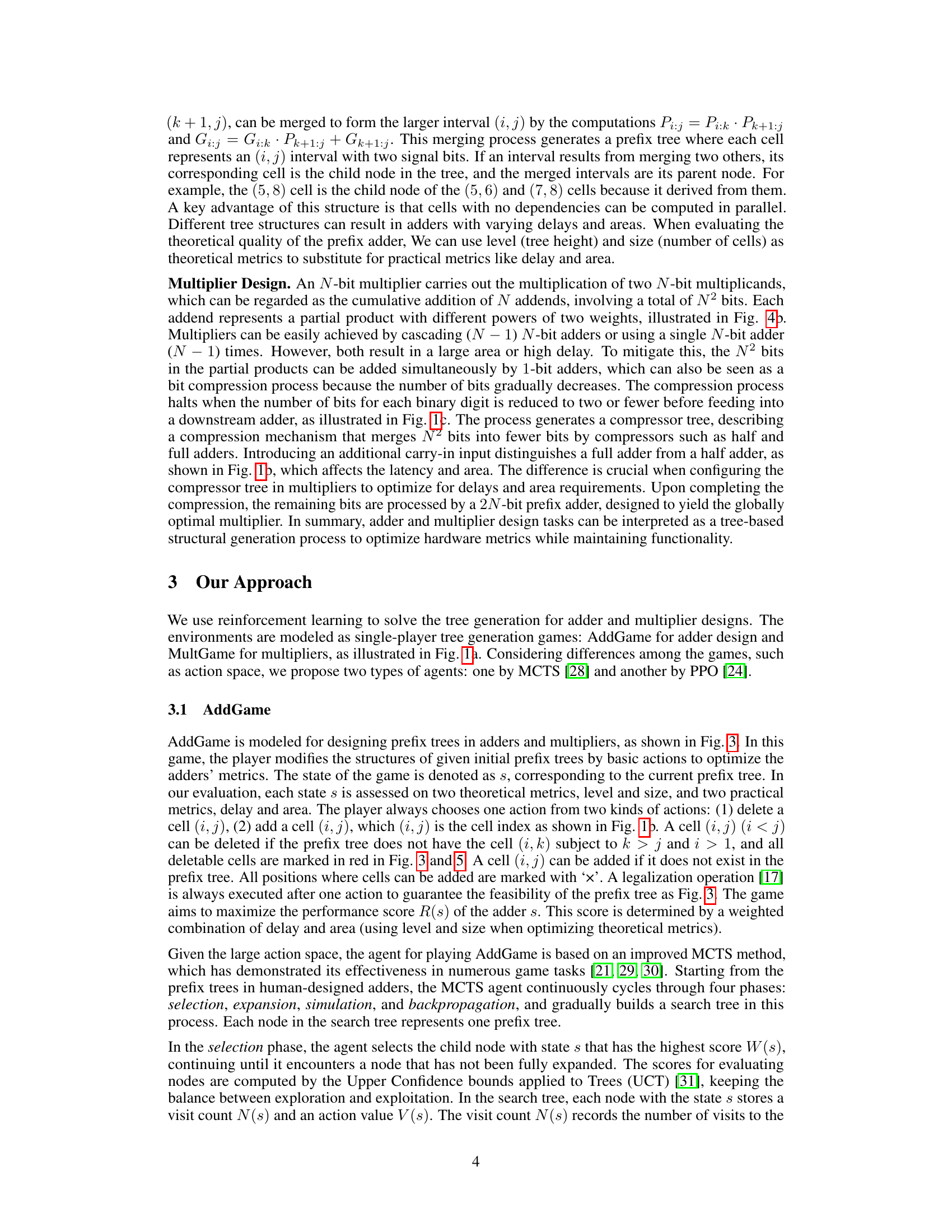

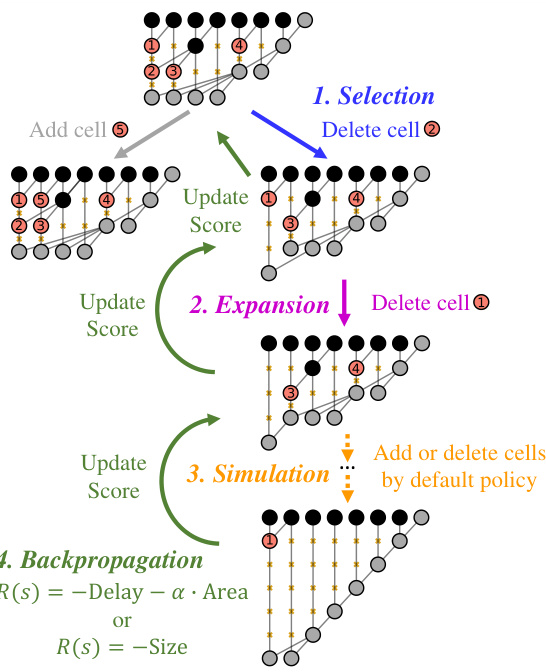

This figure shows the four phases of the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) method used for designing prefix trees in adders and multipliers. The phases are: 1. Selection: The agent selects the most promising node in the search tree based on a combination of exploration and exploitation. The example shows deleting cell 2. 2. Expansion: A new child node is added to the tree representing a new prefix tree design. The example shows deleting cell 1. 3. Simulation: A simulation is run from the new node to evaluate the quality of the new design. This involves making more modifications based on a default policy. Add or delete cells is shown. 4. Backpropagation: The result of the simulation is used to update the scores of all nodes along the path from the root to the new node. The score is determined by a weighted combination of delay and area (theoretical metrics) or delay and area (practical metrics). The figure illustrates how these phases iteratively build a search tree to discover optimal prefix tree structures for adders and multipliers.

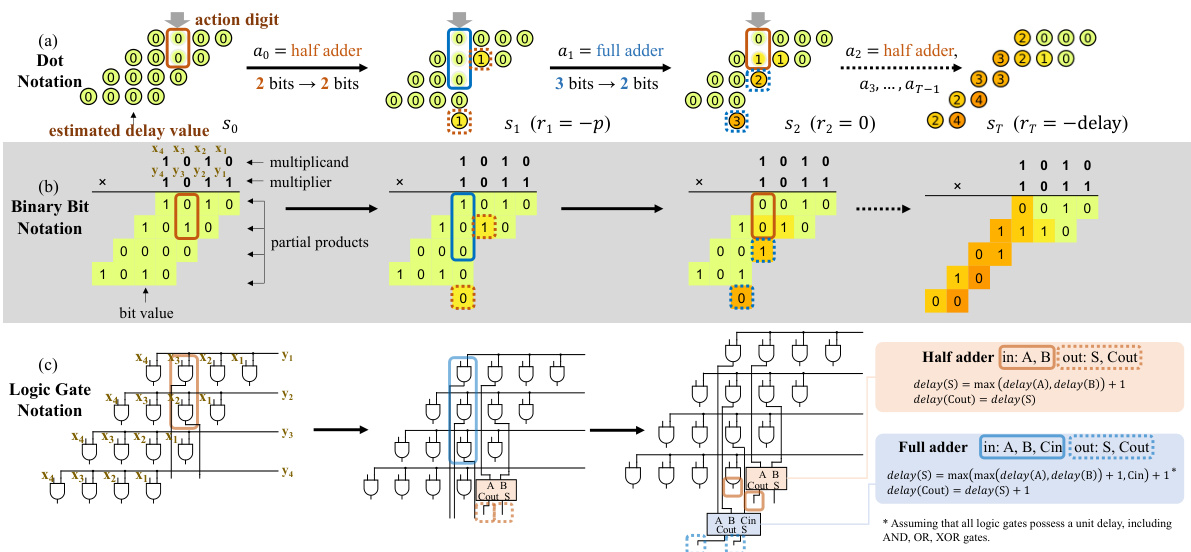

This figure illustrates three representations of the process of designing compressor trees using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO). The dot notation (a) shows each bit with an estimated delay, guiding the agent’s choices in adding half or full adders to reduce bits to at most two per digit, maximizing the final reward (inverse of delay). Binary bit notation (b) demonstrates the process with example multiplication values. Logic gate notation (c) shows the circuit designs generated at each step.

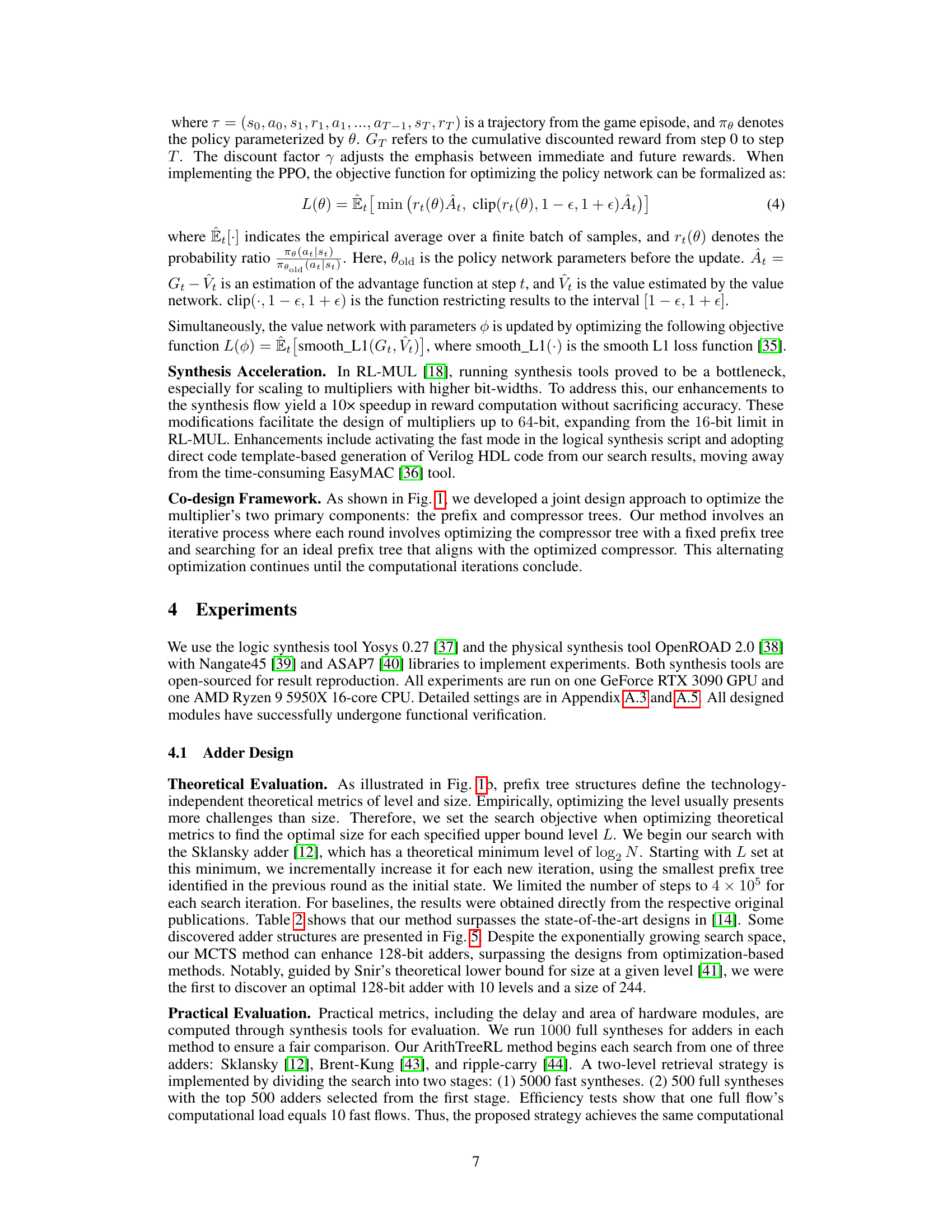

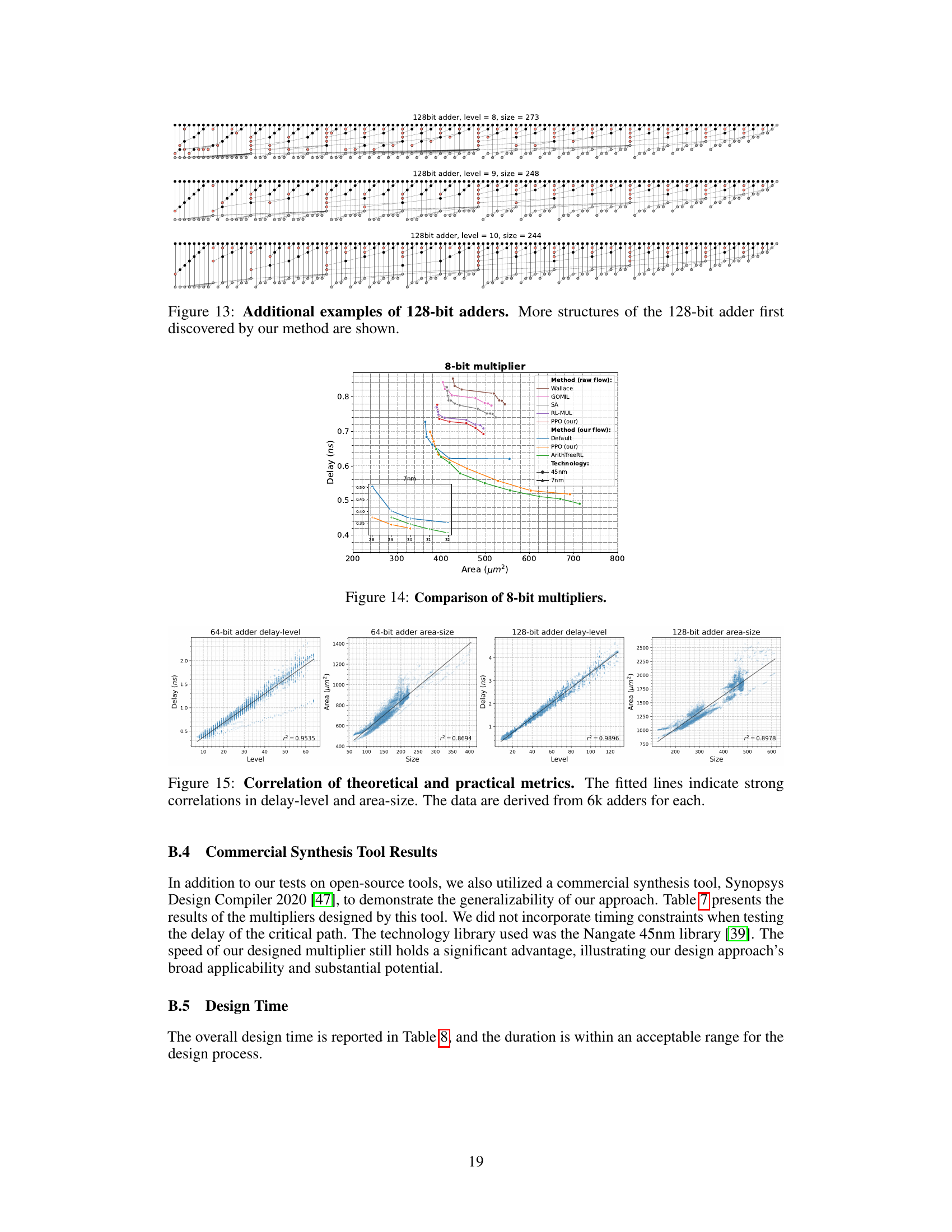

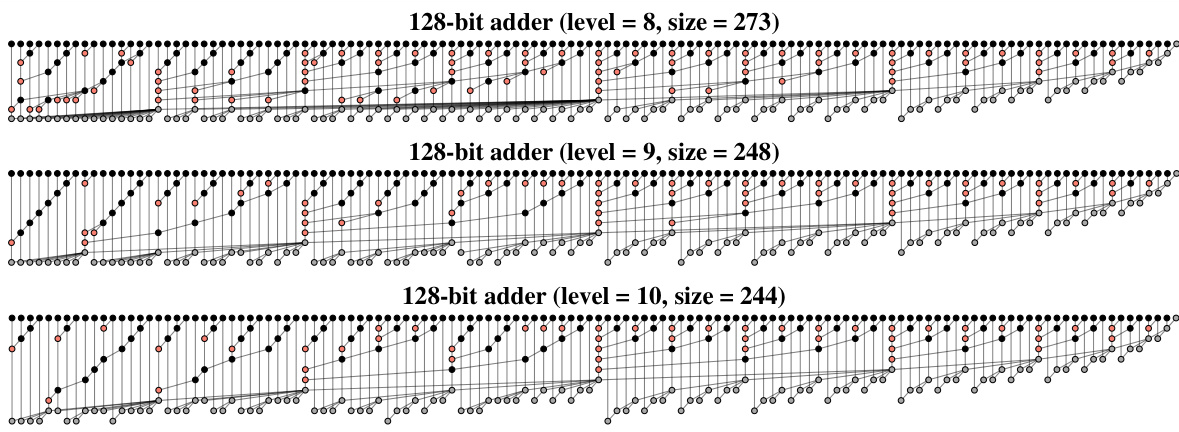

This figure shows three different prefix tree structures discovered by the ArithTreeRL algorithm for 128-bit adders. Each tree represents a different design with varying levels and sizes, achieving the smallest sizes for their corresponding levels. The visual representation uses nodes to depict the (i,j) intervals in the prefix tree, highlighting how these intervals are merged to compute the final sum. These trees showcase the algorithm’s ability to find optimal or near-optimal solutions in the vast search space of adder designs, leading to improvements in both theoretical and practical metrics like delay and area.

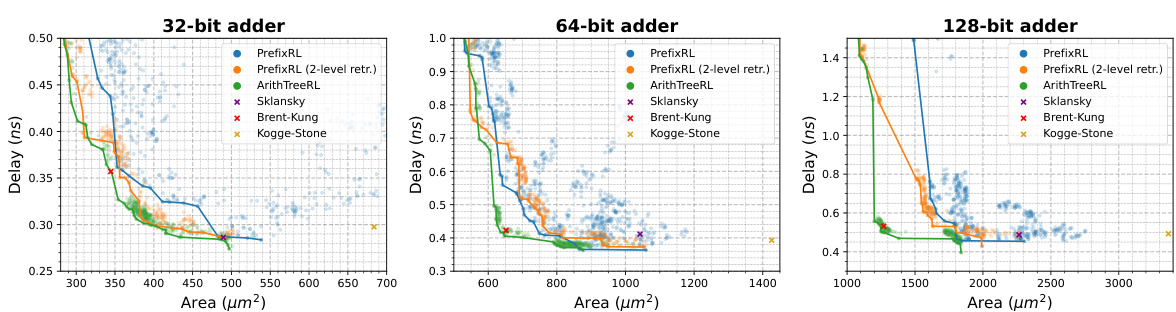

This figure compares the performance of different adder designs in terms of delay and area. It shows that the proposed ArithTreeRL method significantly outperforms existing methods, especially for larger adders (64-bit and 128-bit). The two-level retrieval strategy used in ArithTreeRL further enhances its performance by efficiently exploring the design space.

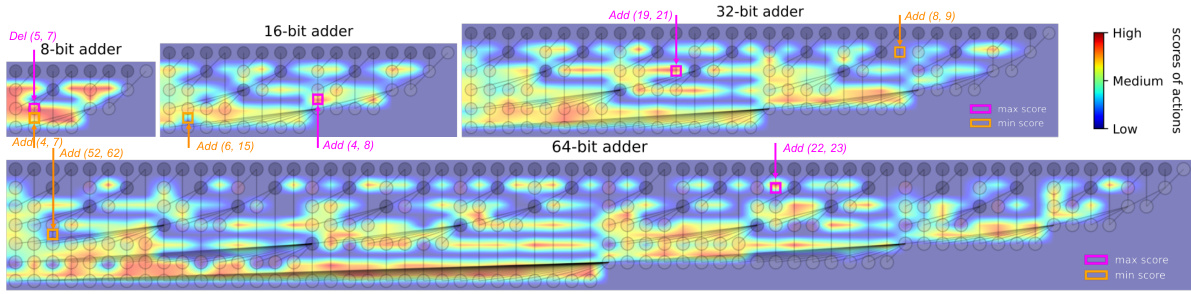

This figure illustrates the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) algorithm used for designing prefix trees in adders and multipliers. The MCTS algorithm iteratively cycles through four phases: selection, expansion, simulation, and backpropagation to build a search tree. Each node in the tree represents a prefix tree, and the algorithm progressively refines the tree structure by selecting actions that maximize a performance score based on delay and area metrics. The actions include adding or deleting cells in the prefix tree.

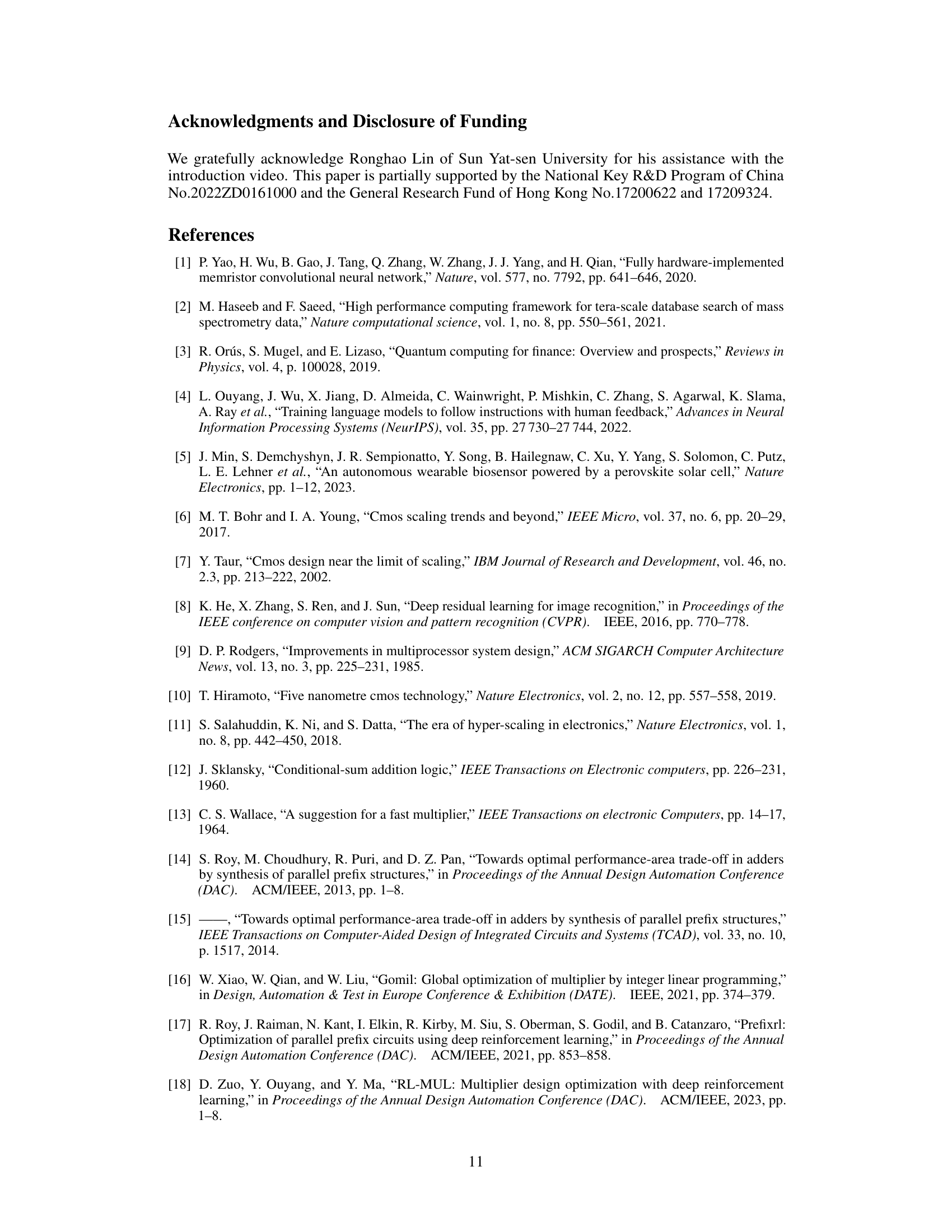

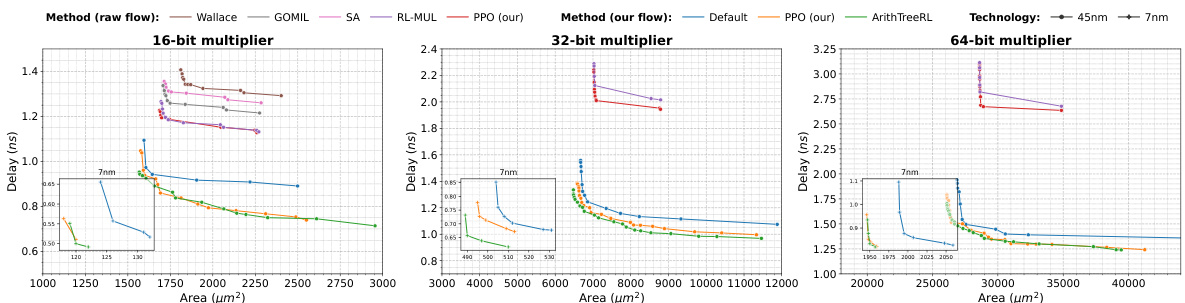

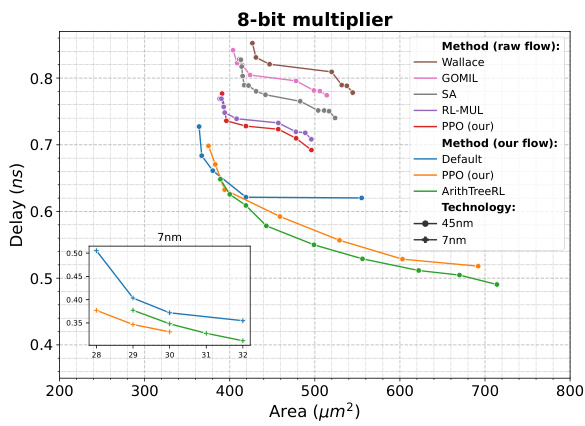

This figure compares the performance of different multiplier designs, including the proposed ArithTreeRL method, across various bit widths (8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit). The performance is evaluated using delay and area metrics under different timing constraints, showcasing the Pareto optimality of the designs. The figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the co-design approach and the transferability of 45nm designs to 7nm technology.

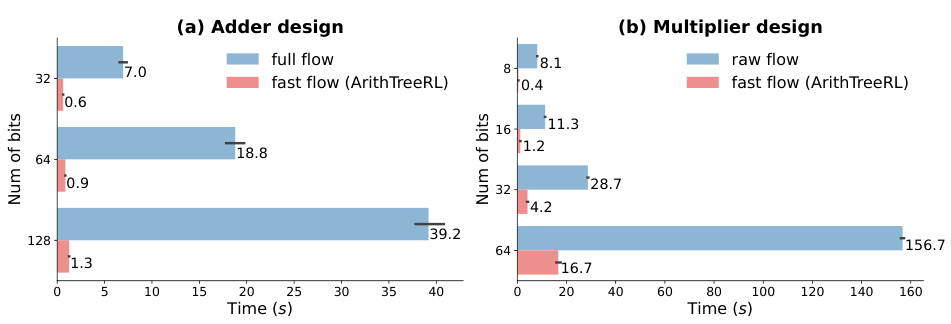

This figure compares the time consumption of the full synthesis flow and the fast synthesis flow (proposed in ArithTreeRL) for both adder and multiplier designs. For adders, the fast flow shows a significant reduction in time consumption compared to the full flow, especially for larger bit sizes. Similarly, for multipliers, the fast flow proposed by ArithTreeRL is faster than the raw flow, especially at larger bit sizes. This demonstrates the efficiency improvement achieved by using the two-level retrieval strategy in ArithTreeRL, enabling faster design exploration.

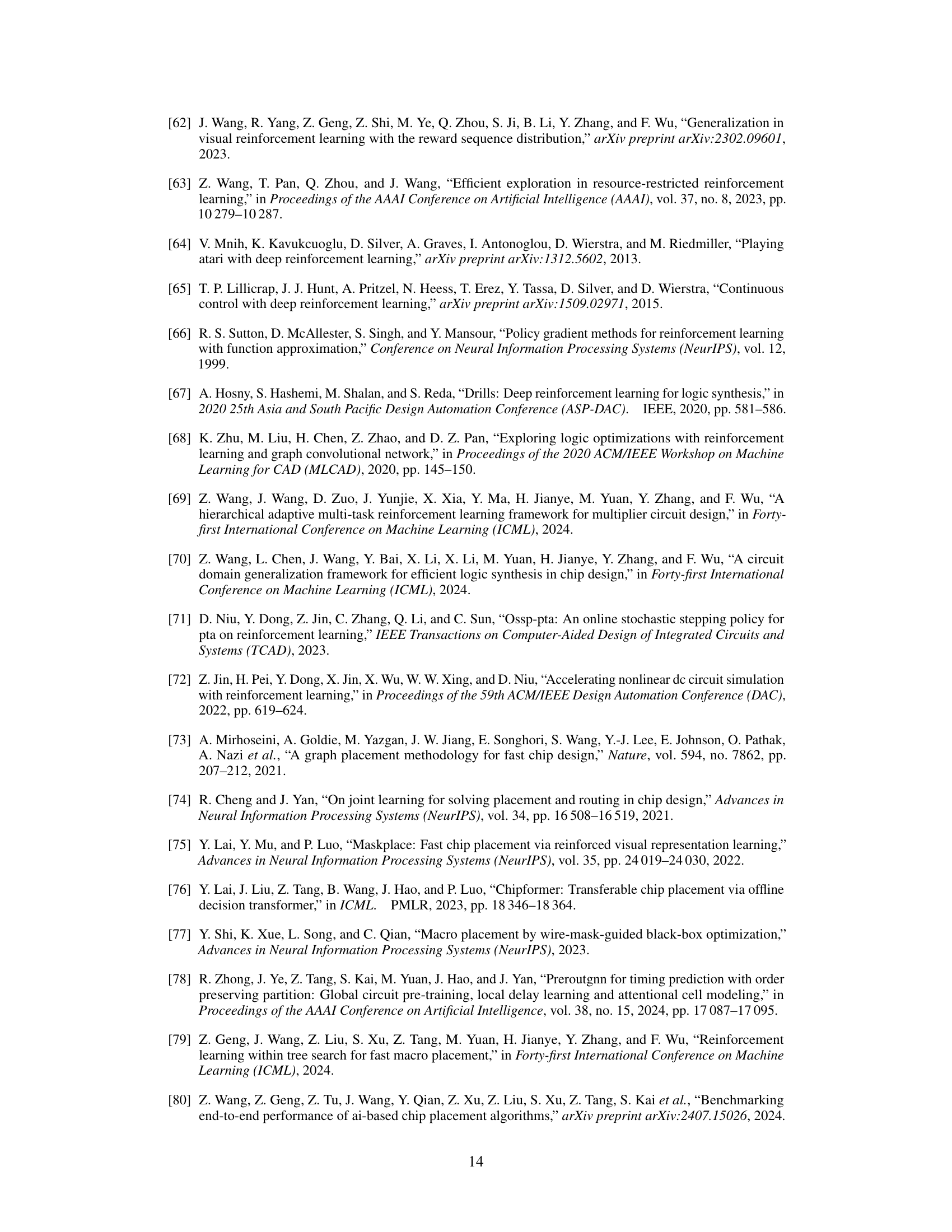

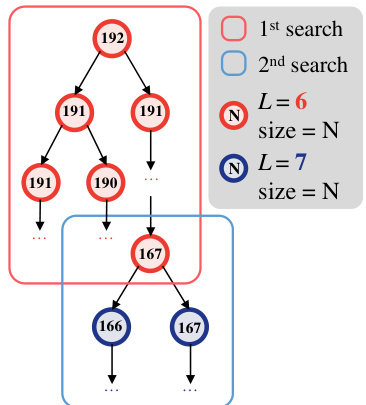

This figure illustrates the process of optimizing adders using a stratified search based on level upper bounds. The search starts with a specified level, and the best adder is then used as the starting point for the next search with a higher level. This iterative process helps to efficiently find optimal adders.

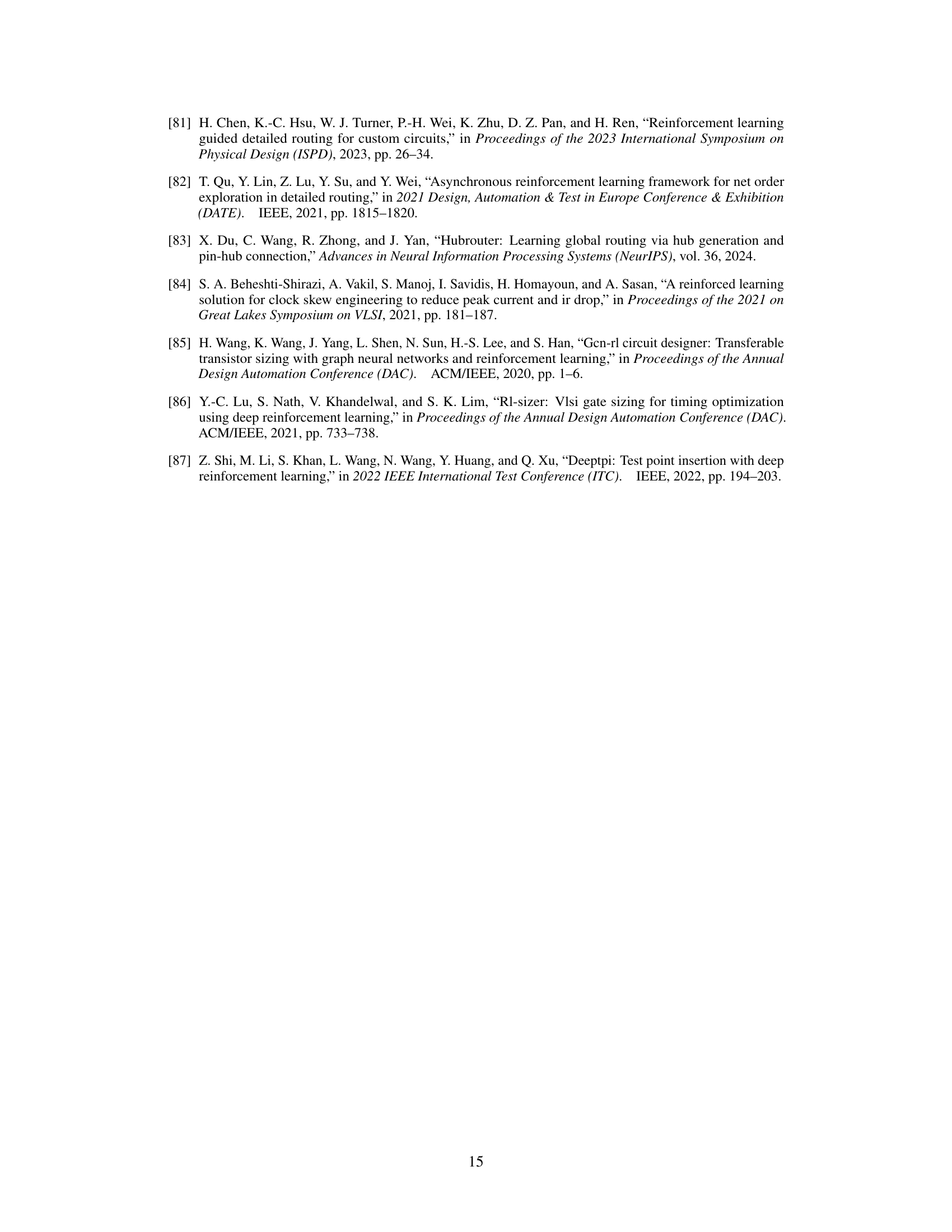

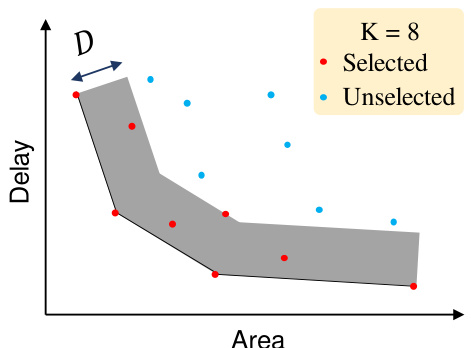

This figure illustrates the selection process in the two-level retrieval strategy used for adder design. After a first stage of fast synthesis, adders are plotted on a graph with delay on the y-axis and area on the x-axis. The Pareto front (optimal tradeoff between delay and area) is identified. The K (in this case, 8) adders closest to the Pareto front are selected for a second stage of full (more accurate but slower) synthesis. The distance D represents the threshold distance used for selection.

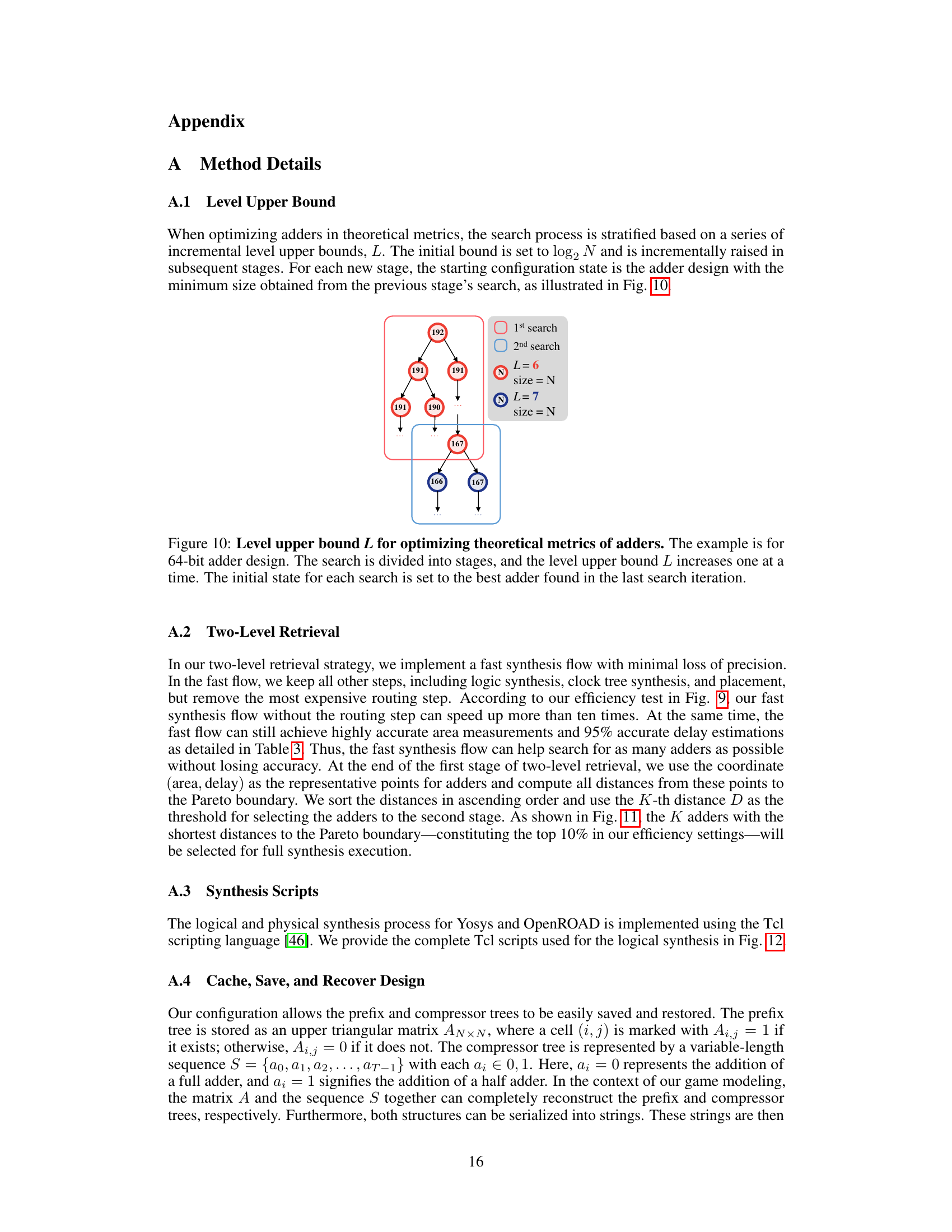

This figure illustrates the ArithTreeRL framework, showing how two reinforcement learning agents optimize the prefix and compressor trees for adders and multipliers. It also provides visual representations of a prefix tree and a compressor tree, highlighting how different tree structures impact the performance of the resulting adder and multiplier designs.

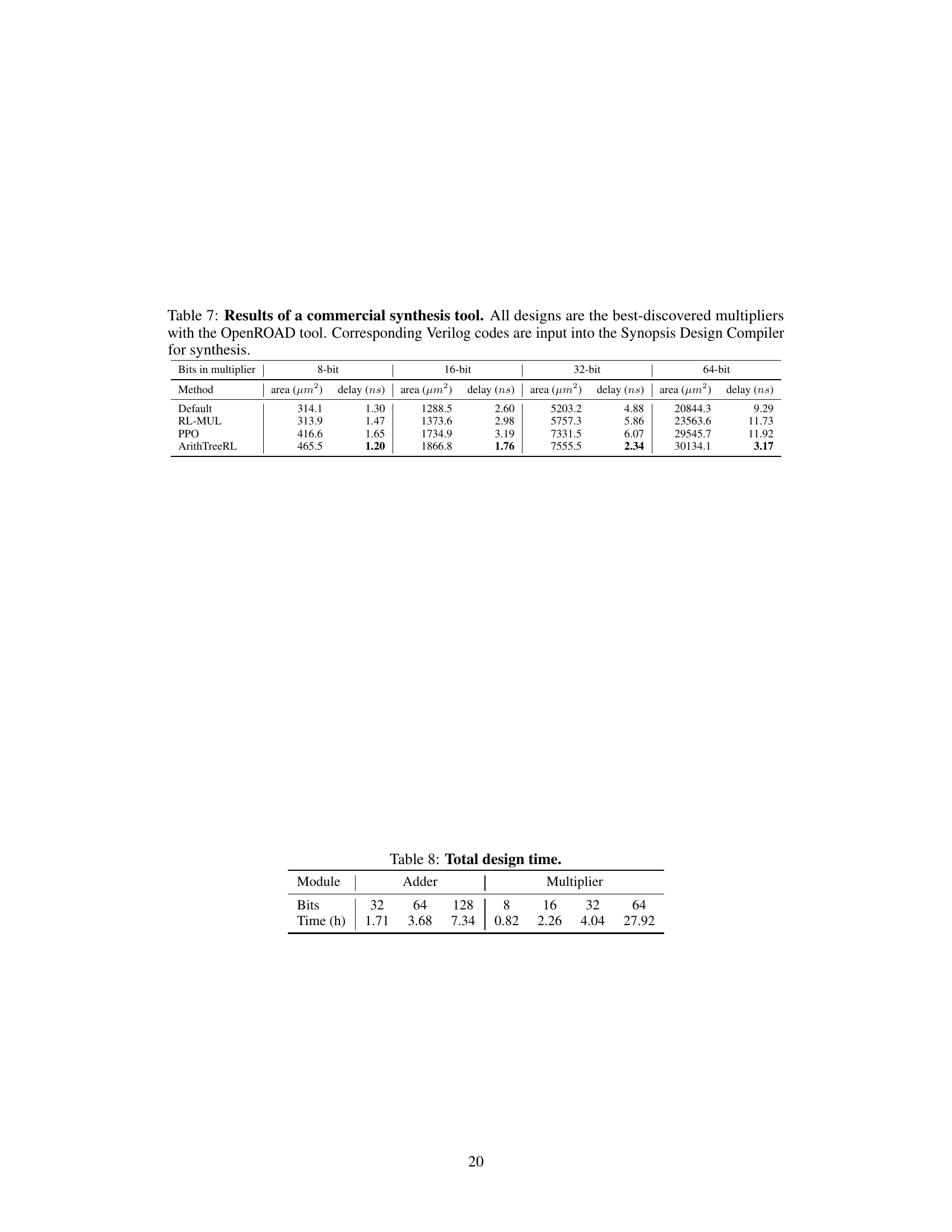

The figure compares the performance of different multiplier designs for an 8-bit multiplier in terms of delay and area. The designs compared include Wallace, GOMIL, SA, RL-MUL, PPO (our), Default, ArithTreeRL (our). The results are shown for both 45nm and 7nm technologies. ArithTreeRL shows improvements over existing methods, especially in terms of delay.

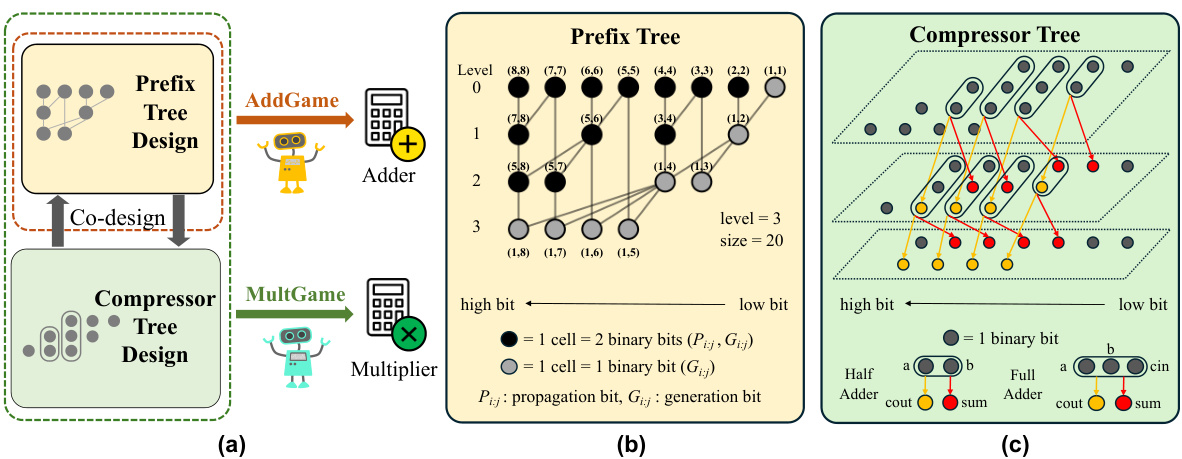

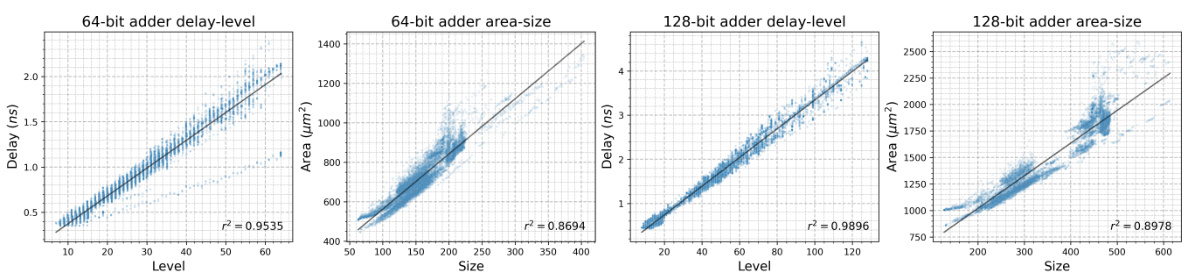

This figure shows the strong correlation between theoretical metrics (level and size) and practical metrics (delay and area) for adders. The plots demonstrate that adders with lower levels (tree height) and smaller sizes tend to have lower delays and smaller areas. This validates the use of theoretical metrics as a proxy for practical performance in the optimization process.

More on tables

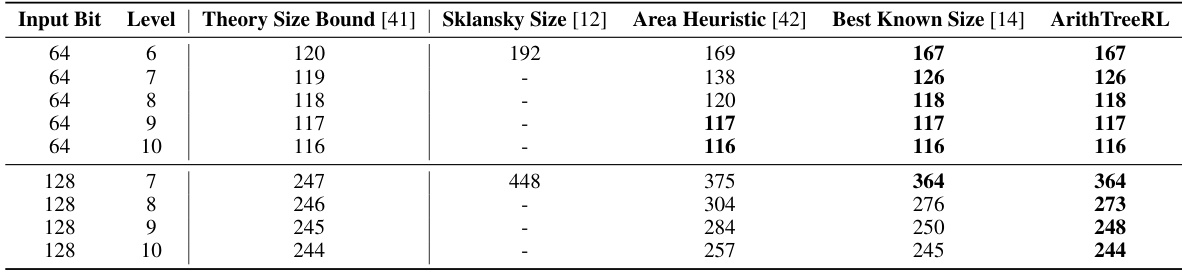

This table compares the size of 64-bit and 128-bit adders designed using different methods. It shows the theoretical size lower bound and the sizes obtained by the Sklansky adder, an area heuristic method, the previously best-known sizes from literature, and the sizes achieved by the ArithTreeRL method proposed in the paper. Smaller sizes are generally preferred in hardware design because they result in smaller and faster circuits.

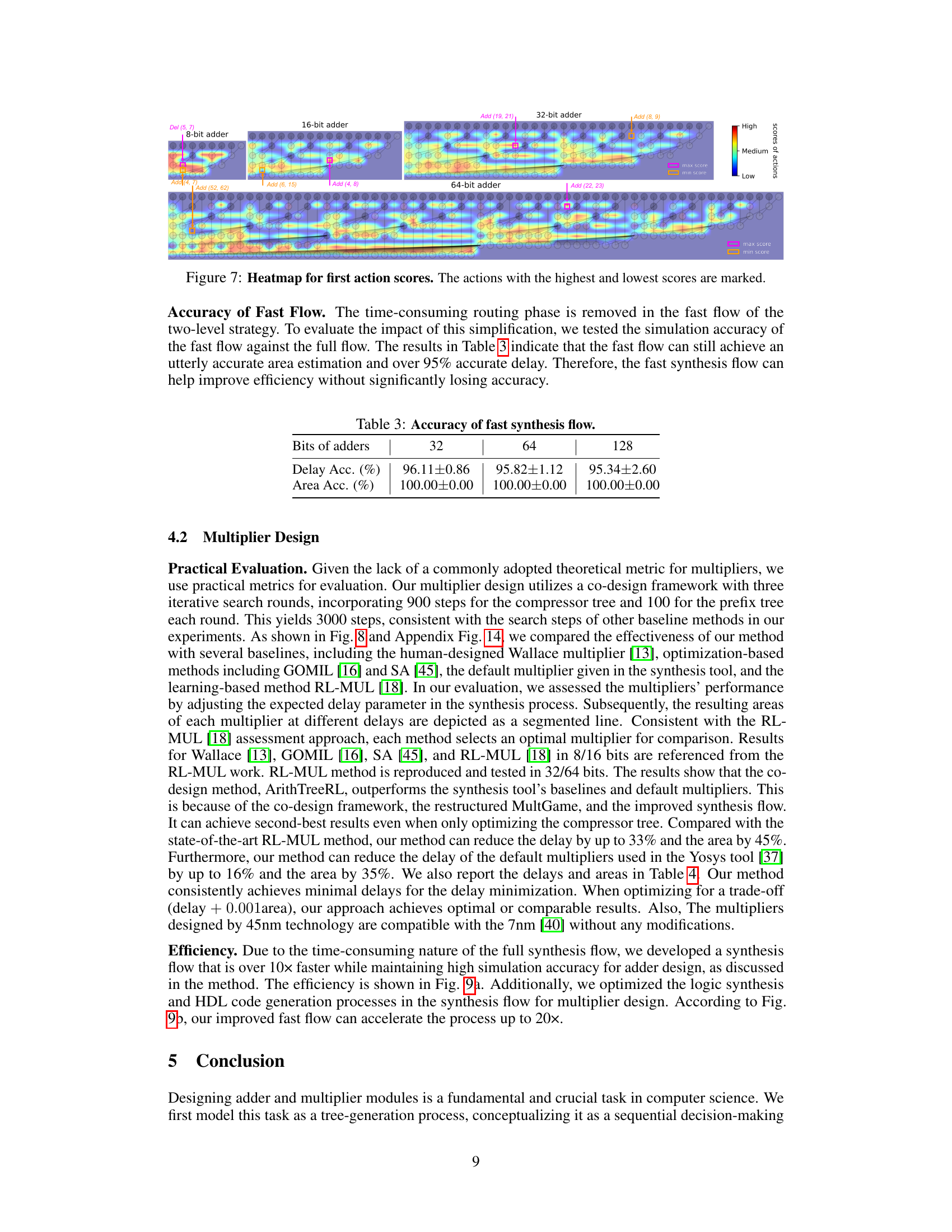

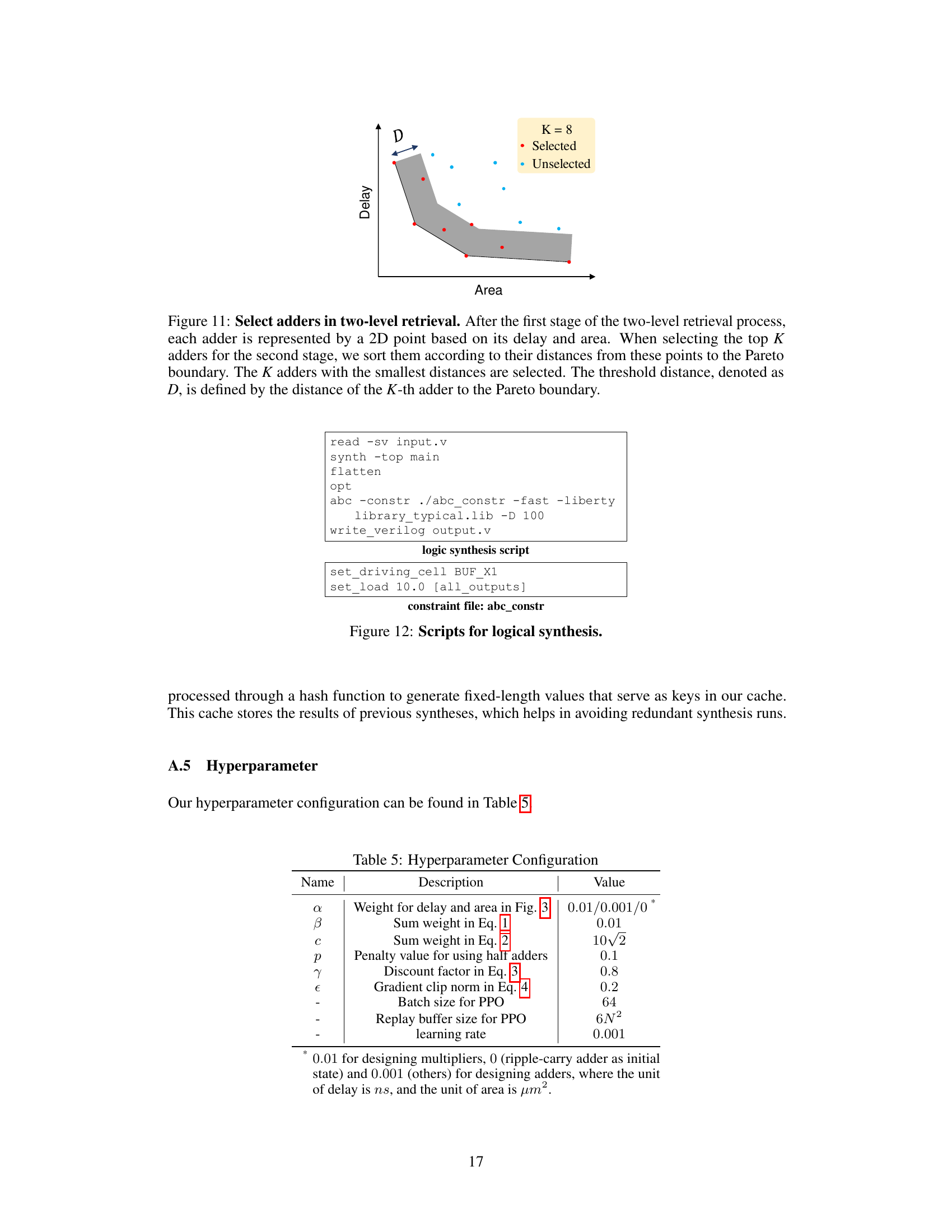

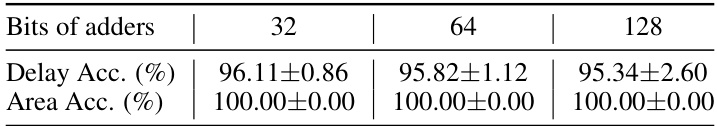

This table shows the accuracy of the fast synthesis flow compared to the full synthesis flow for adders with different bit widths. The fast flow omits the routing step for increased speed. The accuracy is assessed by comparing the delay and area estimations from the fast flow to the values obtained via the full flow. The results show a high accuracy for area and over 95% accuracy for delay, demonstrating that the speedup of the fast flow does not come at a significant loss of accuracy.

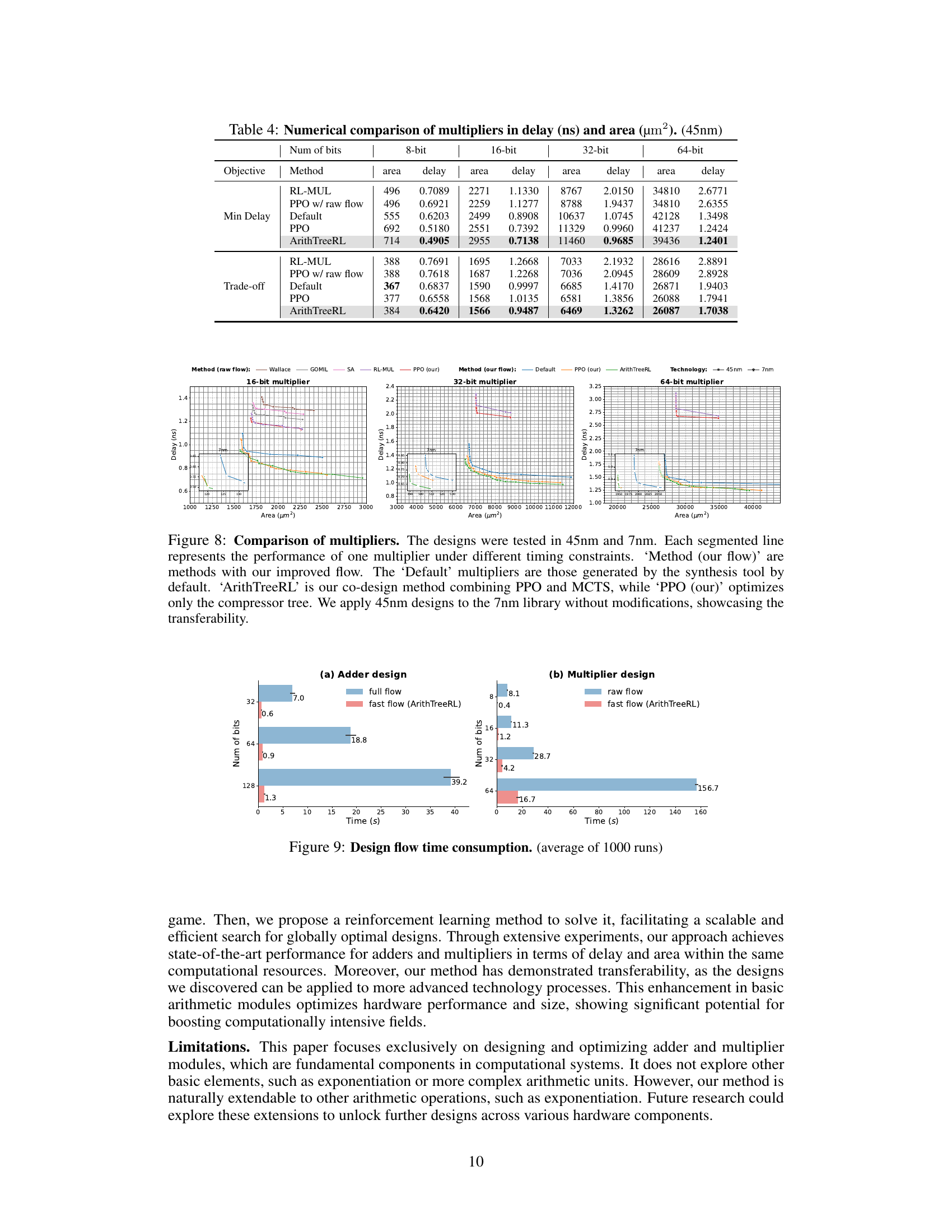

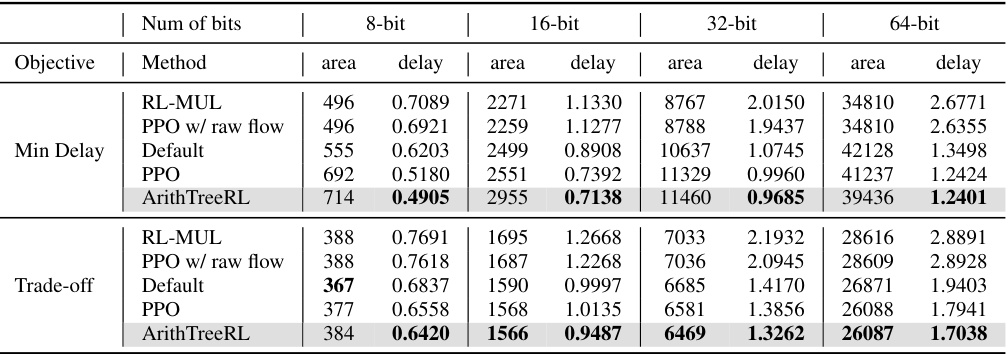

This table presents a numerical comparison of multipliers in terms of delay (in nanoseconds) and area (in square micrometers), using a 45nm technology node. The comparison includes several different methods: RL-MUL, PPO with raw flow, the default method, PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization), and the ArithTreeRL method proposed in the paper. For each method, the minimum delay and a trade-off objective (delay + 0.001area) are considered. Results are provided for 8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit multipliers. The table allows for a direct comparison of the performance of each method in terms of both delay and area, highlighting the improvements achieved by the ArithTreeRL approach.

This table presents a numerical comparison of different multiplier designs in terms of delay (in nanoseconds) and area (in square micrometers), specifically using a 45nm technology. The comparison includes results from RL-MUL, the PPO method with raw and improved synthesis flow, and the default multiplier generated by the synthesis tool. Results are shown for minimizing delay, minimizing area, and a trade-off between delay and area. The table allows for a quantitative assessment of the performance improvements achieved by different approaches.

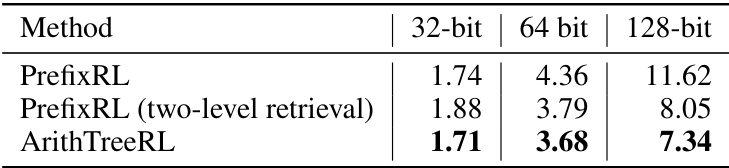

This table shows the time spent on designing adders using different methods for three different bit sizes (32-bit, 64-bit, and 128-bit). The methods compared are PrefixRL, PrefixRL with a two-level retrieval strategy, and the authors’ proposed ArithTreeRL method. The numbers in the table represent the total time (in hours) required to complete the design process for each method and bit size. The two-level retrieval strategy significantly reduces the total time for the PrefixRL design process. ArithTreeRL shows efficient time consumption compared to the other two methods.

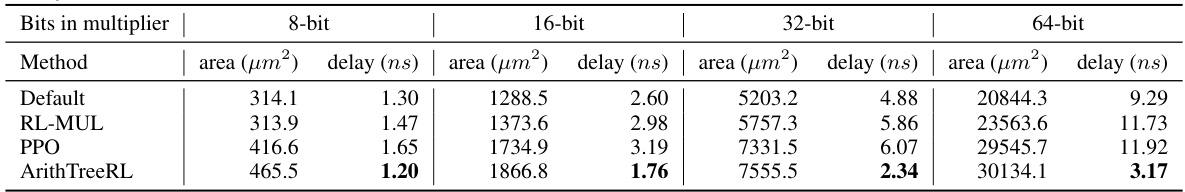

This table presents the results obtained using Synopsys Design Compiler, a commercial synthesis tool, for the best-performing multipliers previously discovered using the OpenROAD tool. It compares the area and delay of four different multiplier designs (Default, RL-MUL, PPO, and ArithTreeRL) across various bit widths (8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit). The data demonstrates the effectiveness of ArithTreeRL in achieving superior performance in terms of both delay and area compared to the baseline methods.

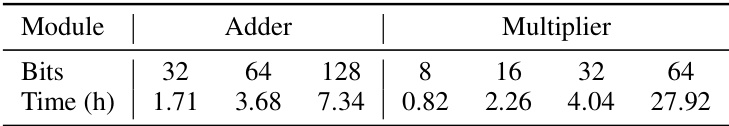

This table shows the total time (in hours) taken to design adders and multipliers with different bit widths using the proposed ArithTreeRL method. The time includes all steps of the design process, from initial design exploration to final synthesis. The table shows that the design time increases with the number of bits, reflecting the increased complexity of the design process for larger bit-widths.

Full paper#