↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Solving extensive-form games (EFGs) efficiently is crucial in AI, especially for complex games like poker. Current methods, though theoretically fast, often struggle with practical performance due to stepsize sensitivity. This limits their applicability in large-scale games. Furthermore, the exceptional performance of existing algorithms like CFR+ remains unexplained.

This paper introduces the first algorithmic framework for Blackwell approachability on treeplexes (sequence-form polytopes representing player strategies in EFGs). This leads to a new class of regret-minimization algorithms. The researchers introduce Predictive Treeplex Blackwell+ (PTB+) which achieves a state-of-the-art O(1/T) convergence rate to Nash equilibrium. The method is then compared to existing benchmarks, highlighting interesting connections between practical performance and stepsize-invariance properties. The results show that stepsize invariance is crucial for practical performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on extensive-form game solving, as it introduces a novel framework based on Blackwell approachability, offering stepsize-invariant algorithms. This addresses a major limitation in existing methods and could greatly improve practical performance. The insights on stepsize invariance also provide a new perspective on the success of existing algorithms, opening avenues for future research into more efficient and robust solutions.

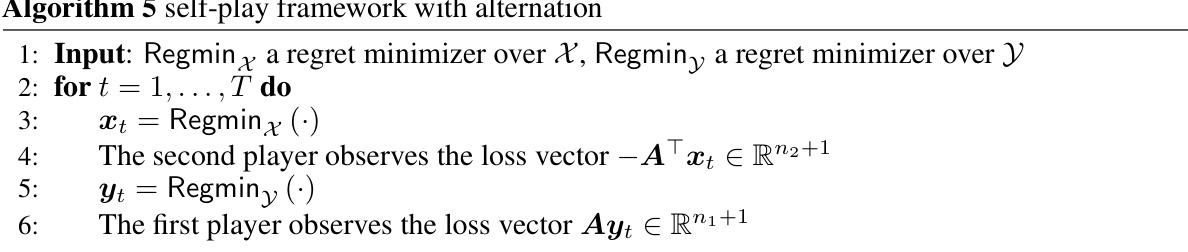

Visual Insights#

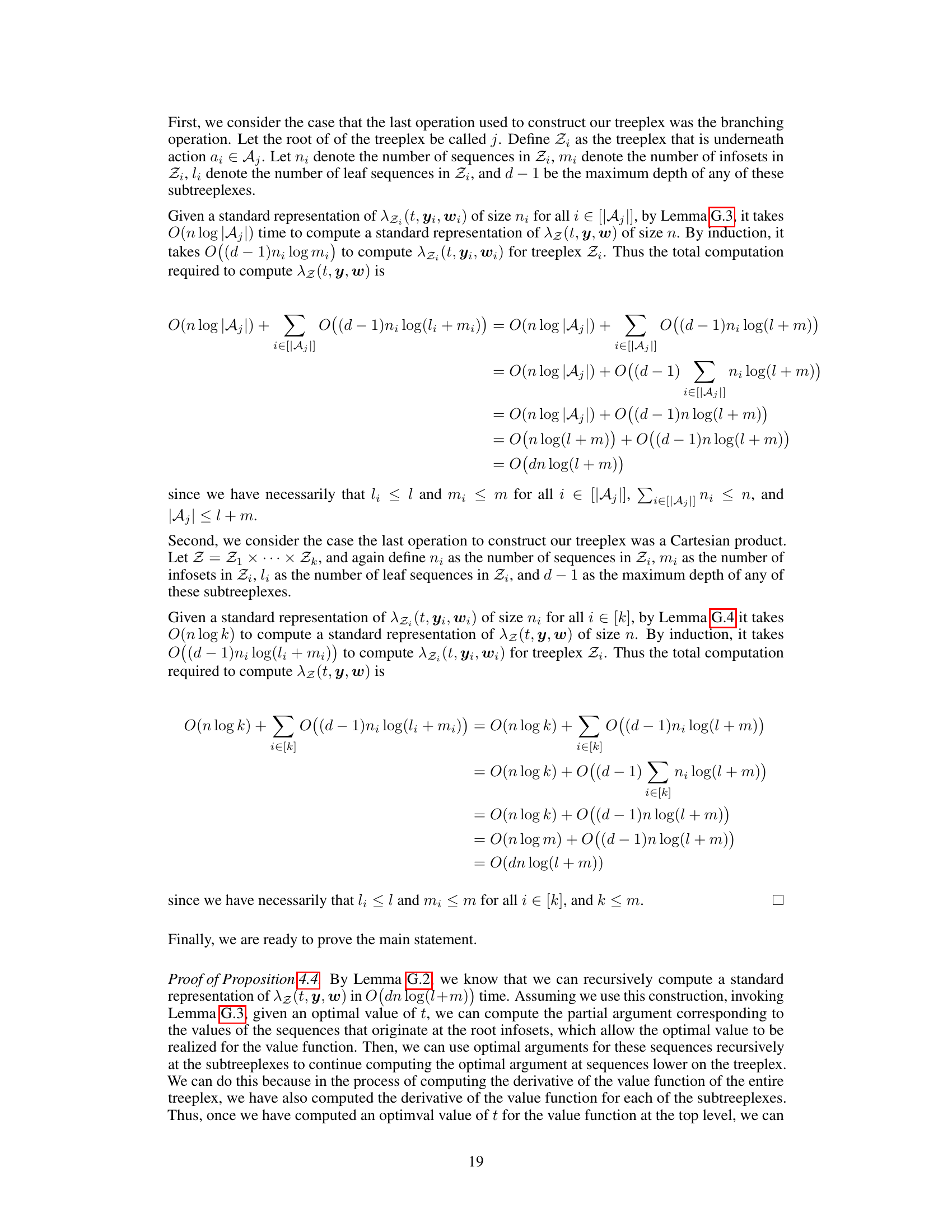

This figure illustrates the dynamics of the Regret Matching+ (RM+) algorithm in two dimensions (R²). It shows how the regret vector Rt is updated iteratively. The vector gt represents the instantaneous loss at iteration t, which is projected onto the simplex (∆²) to obtain the next strategy xt. The algorithm maintains a running sum of regrets (Rt), and the strategy xt at each step is obtained by normalizing this sum. The stepsize η is implicitly present in the update rule; the algorithm is stepsize invariant because only the direction, and not the magnitude, of Rt matters for determining xt.

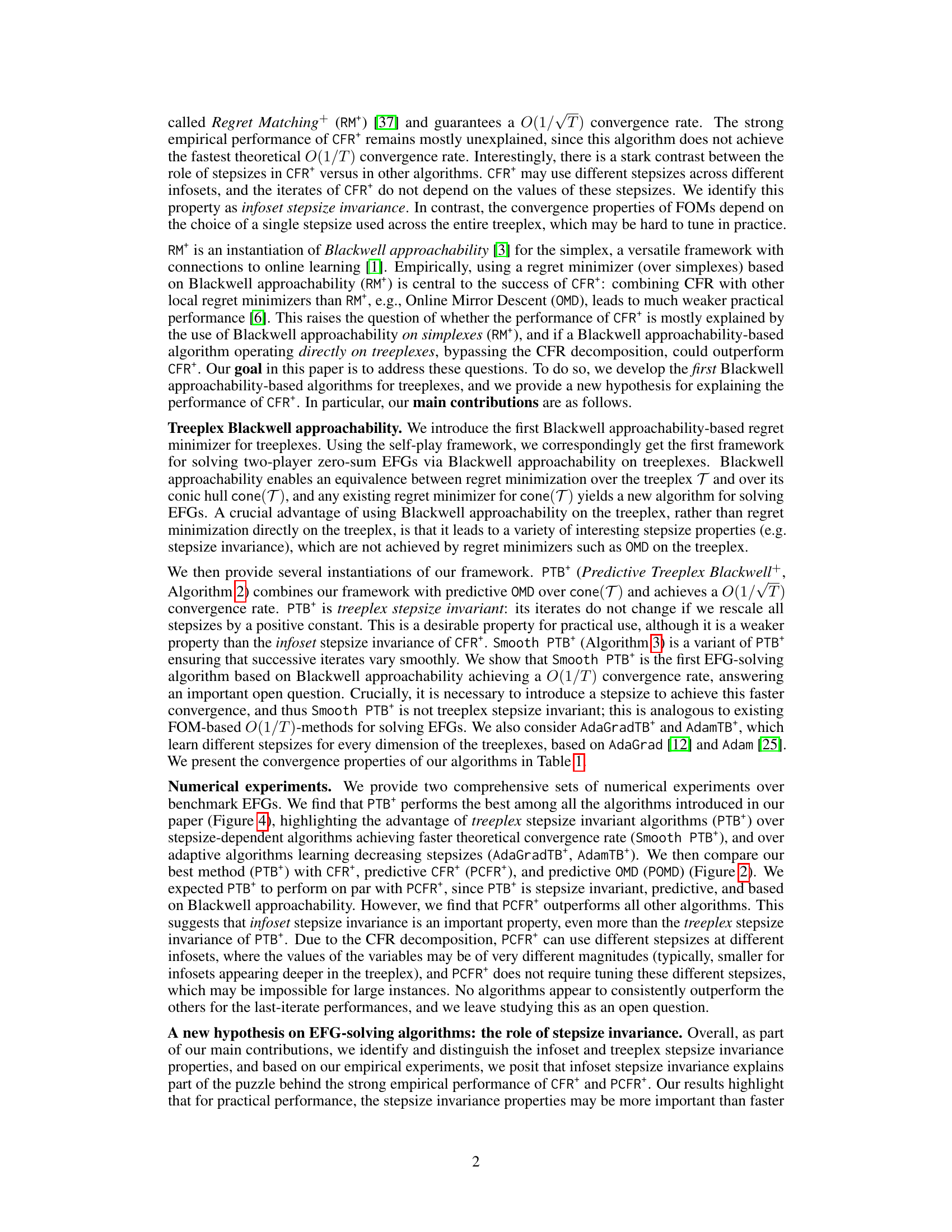

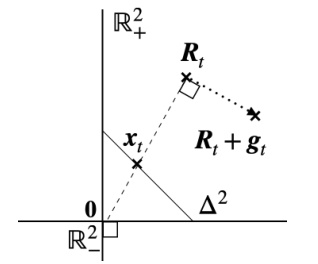

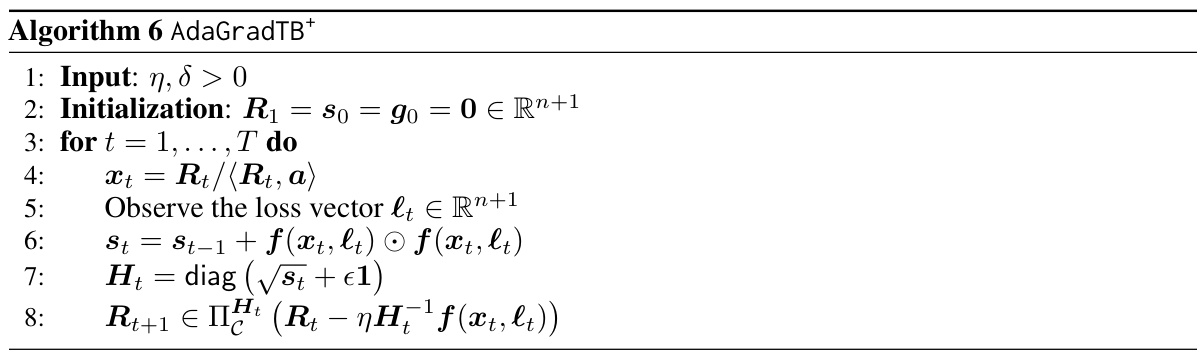

This table summarizes the convergence rates and stepsize invariance properties of several algorithms for solving two-player zero-sum extensive-form games (EFGs). The convergence rate indicates how quickly the algorithm approaches a Nash equilibrium, while stepsize invariance refers to whether the algorithm’s performance is affected by the choice of stepsize. Infoset stepsize invariance means that different stepsizes can be used across different infosets in the game tree without affecting convergence. Treeplex stepsize invariance refers to whether the algorithm’s performance depends on the choice of a single stepsize across the entire treeplex.

In-depth insights#

Treeplex Approach#

The Treeplex Approach, as described in the research paper, presents a novel algorithmic framework for solving extensive-form games (EFGs). It leverages the mathematical properties of treeplexes—sequence-form polytopes representing player strategies—to develop stepsize-invariant regret minimization algorithms. Unlike traditional methods relying on CFR (Counterfactual Regret Minimization), which decompose the problem into simpler subproblems, this approach directly tackles the regret minimization problem over the entire treeplex. This leads to algorithms that are more robust to stepsize choices and often exhibit superior empirical performance. The modular framework allows integration with various regret minimizers, enabling the development of algorithms with different convergence rates and stepsize invariance properties. Key contributions include the introduction of Predictive Treeplex Blackwell+ (PTB+) with a O(1/√T) convergence rate and its stabilized version, Smooth PTB+, which achieves a state-of-the-art O(1/T) rate. The core innovation lies in employing Blackwell approachability on the treeplex, which allows for the equivalence between regret minimization over the treeplex itself and its conic hull, thus enabling the application of a variety of regret minimizers. Numerical experiments demonstrate that stepsize-invariant algorithms, such as PTB+, generally outperform stepsize-dependent algorithms, highlighting the practicality and advantages of this novel approach for EFG solving.

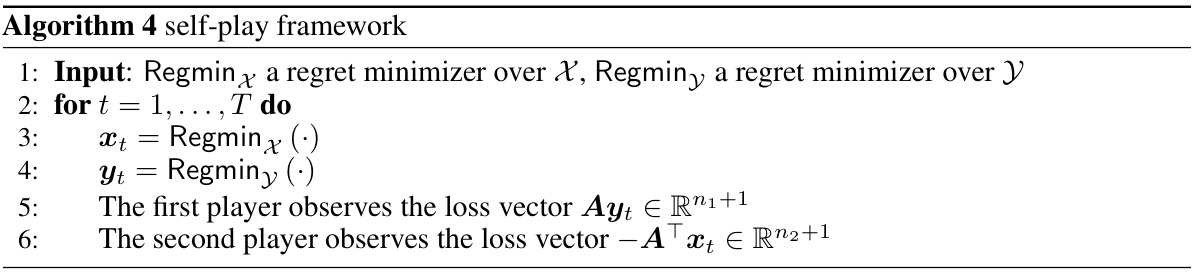

PTB+ Algorithm#

The PTB+ algorithm, a novel method for solving extensive-form games (EFGs), is presented as a stepsize-invariant approach, addressing limitations of existing methods. It leverages Blackwell approachability on the treeplex, a structure representing game strategies, and combines it with predictive online mirror descent. This unique combination yields a O(1/√T) convergence rate to a Nash equilibrium in self-play, exhibiting improved practical performance compared to some prior stepsize-dependent algorithms. The stepsize invariance of PTB+ simplifies tuning, and its modularity allows for combination with other regret minimizers, enhancing its versatility for various game settings. However, empirical results show that, although stepsize-invariant, PTB+ doesn’t match the performance of CFR+, highlighting the importance of infoset-level stepsize properties that CFR+ possesses, as a subject for further study.

Stepsize Invariance#

The concept of stepsize invariance in the context of extensive-form game (EFG) solving algorithms is a crucial one, impacting both theoretical convergence rates and practical performance. Stepsize invariance, meaning algorithm iterates remain unaffected by scaling stepsizes, is a highly desirable property. Algorithms lacking this property often require careful stepsize tuning, a process which becomes increasingly complex as the problem scales. The paper highlights the importance of stepsize invariance, contrasting stepsize-invariant methods, like Regret Matching+, with stepsize-dependent approaches. This distinction is critical because stepsize-invariant algorithms often exhibit superior empirical performance, even if they don’t boast the fastest theoretical convergence rates. Infoset stepsize invariance, a stronger form of invariance, where stepsizes can vary across different infosets without altering iterates, is identified as a possible key to the exceptional performance of CFR+. The paper’s experimental results strongly suggest that stepsize invariance properties, particularly infoset stepsize invariance, are valuable features for effective EFG solvers, sometimes outweighing the theoretical advantage of faster convergence rates obtained through stepsize tuning.

Empirical Findings#

An Empirical Findings section in a research paper would present the results of experiments or observational studies. It should go beyond merely stating the results and delve into a detailed analysis, emphasizing the most important findings. The discussion should compare the obtained results with prior work, highlighting both similarities and discrepancies. Any unexpected or counterintuitive results should be carefully examined and explained. The writing style should be clear, concise, and objective, avoiding speculation or subjective interpretations. The section should also address the limitations of the study and acknowledge potential sources of error or bias. A crucial aspect would be clearly presenting the statistical significance of the results, using appropriate measures such as confidence intervals or p-values. Visual aids such as tables and graphs are usually necessary for clear and effective communication of the findings. The ultimate goal of this section is to provide compelling evidence that supports or refutes the research hypotheses, and to provide a solid foundation for the paper’s conclusions.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the treeplex Blackwell approachability framework to handle imperfect recall games would be a significant advancement, as would adapting it for more complex game structures beyond two-player zero-sum settings. Investigating the theoretical convergence rate of AdamTB+ is crucial, as is further analysis of the interplay between stepsize invariance (both infoset and treeplex) and practical performance. A deeper investigation into the reasons behind the strong empirical performance of CFR+ and its predictive variant, potentially by exploring alternative regret minimizers within the Blackwell approachability framework, is warranted. Finally, bridging the gap between theoretical convergence rates and practical performance by addressing the challenges presented by last-iterate convergence would be a significant contribution to the field.

More visual insights#

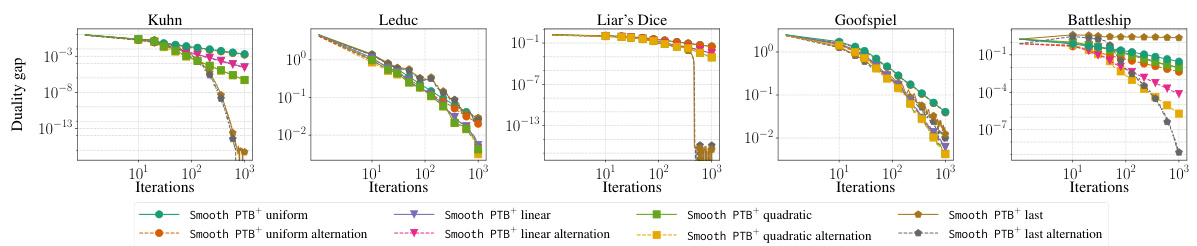

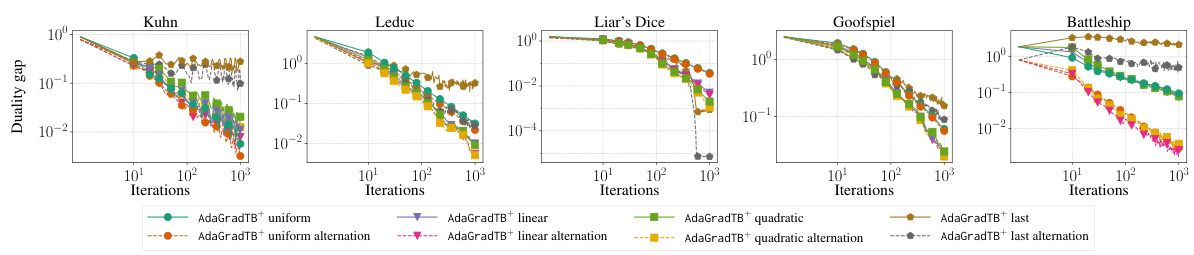

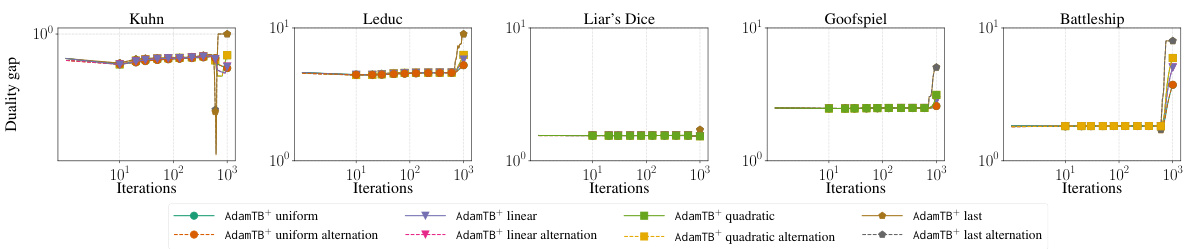

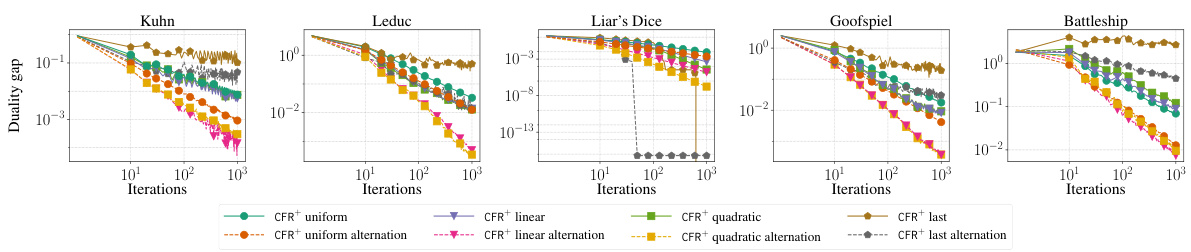

More on figures

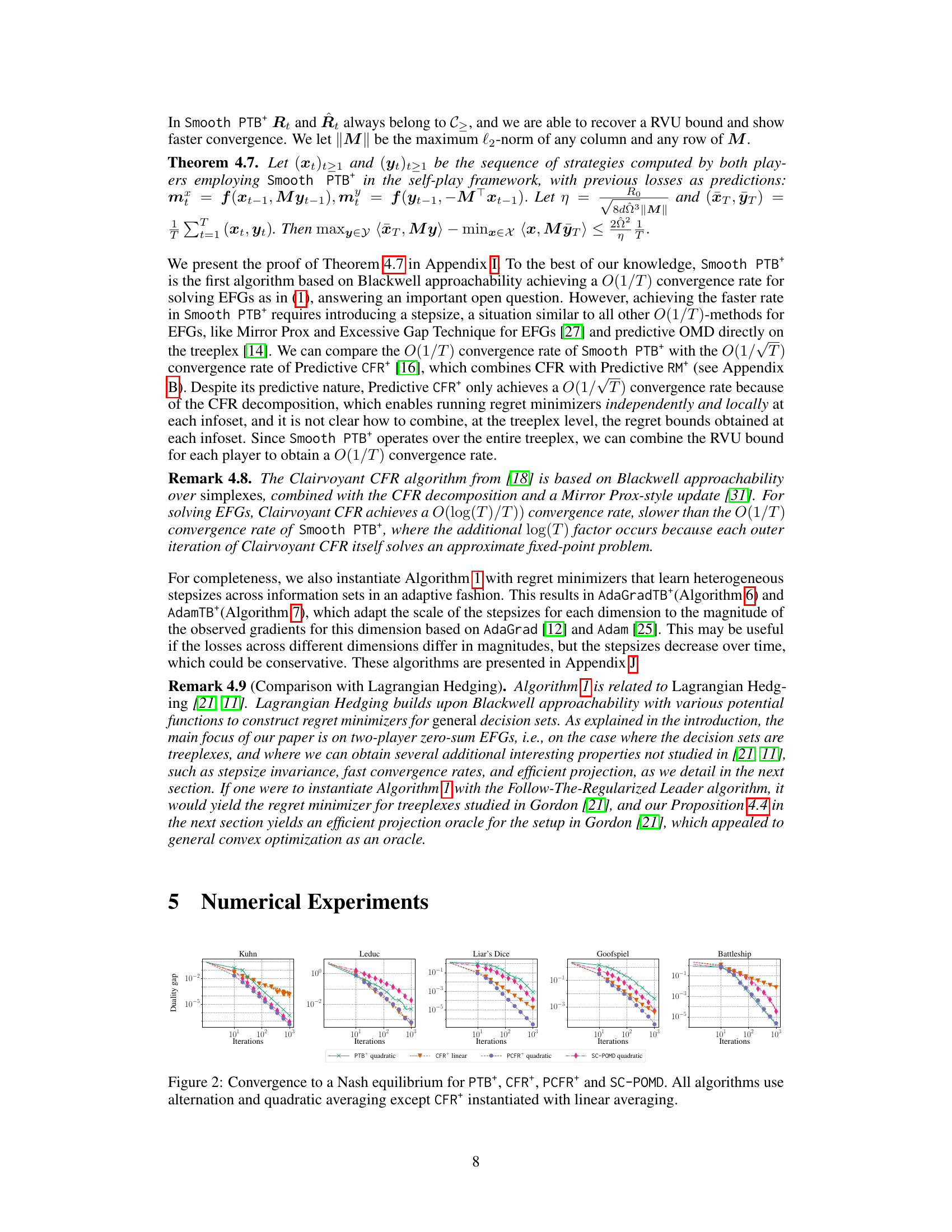

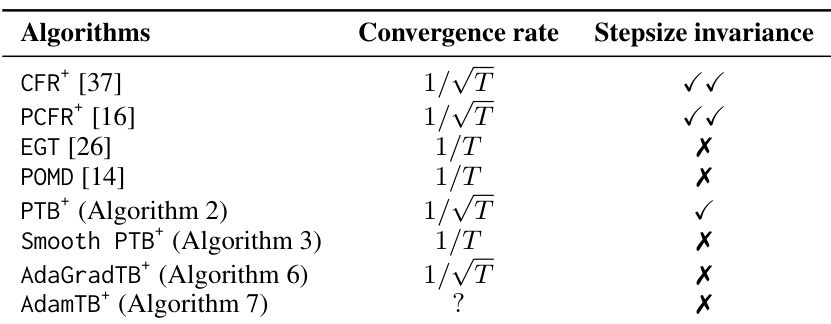

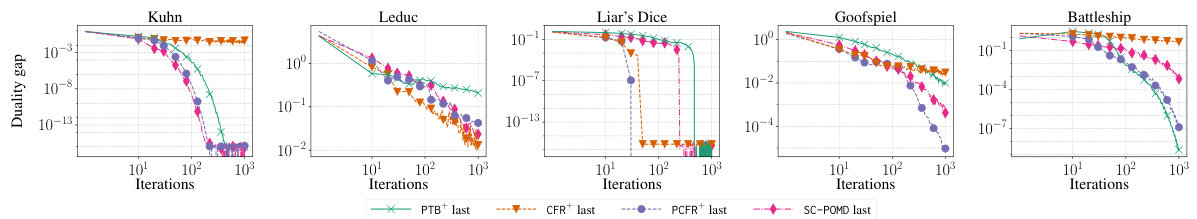

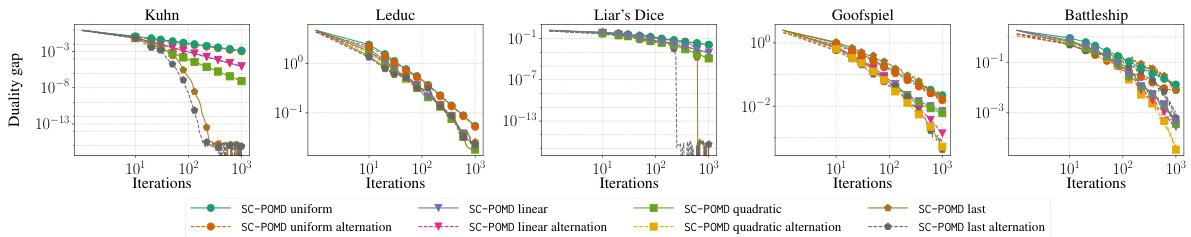

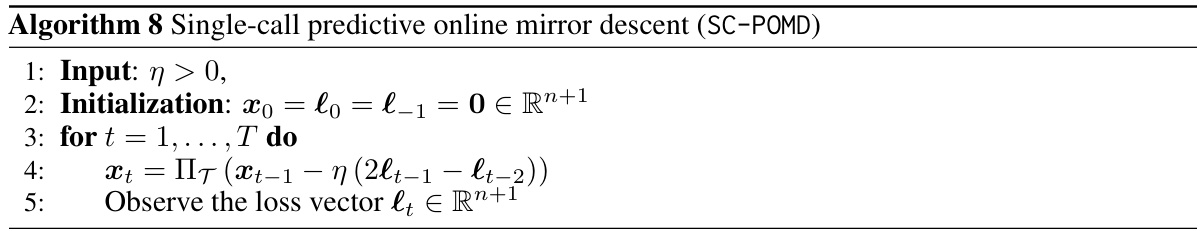

This figure compares the convergence speed of four different algorithms (PTB+, CFR+, PCFR+, and SC-POMD) for solving extensive-form games. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis shows the duality gap, which measures the distance from a Nash equilibrium. The figure shows that PCFR+ generally outperforms the other algorithms, suggesting that its infoset stepsize invariance is an important property. All algorithms use alternation and quadratic averaging, except CFR+, which uses linear averaging.

This figure compares the convergence of four different algorithms (PTB+, CFR+, PCFR+, and SC-POMD) to a Nash equilibrium in several benchmark extensive-form games. The y-axis represents the duality gap, a measure of how far the algorithms are from a solution. The x-axis shows the number of iterations. Note that CFR+ uses linear averaging, unlike the others which utilize quadratic averaging. The figure shows how PTB+ converges relatively quickly compared to CFR+, with PCFR+ and SC-POMD showing intermediate convergence speeds.

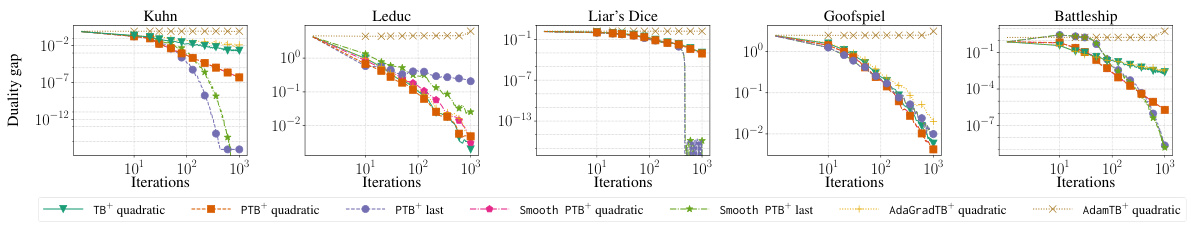

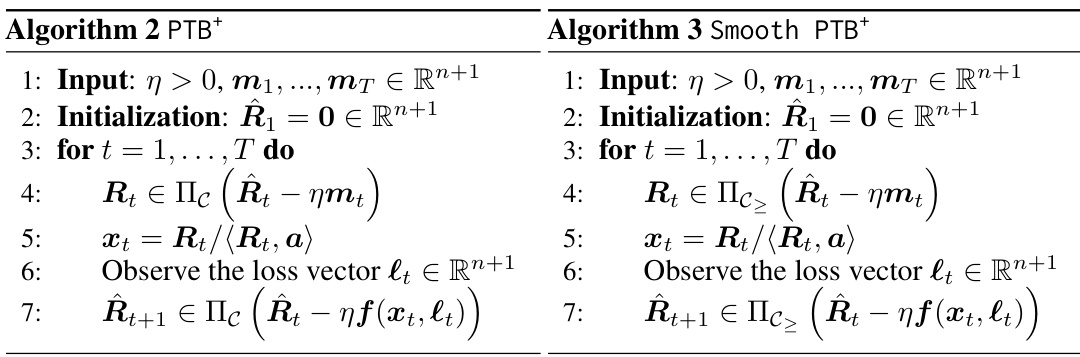

This figure compares the performance of three different algorithms (TB+, PTB+, and Smooth PTB+) for solving extensive-form games. Each algorithm uses a different approach to regret minimization, and the figure shows how quickly they converge to a Nash equilibrium (a stable state in a game). The x-axis represents the number of iterations, while the y-axis shows the duality gap, which measures how far the algorithm is from the equilibrium. The graph displays results for five different benchmark games (Kuhn, Leduc, Liar’s Dice, Goofspiel, and Battleship). The results suggest that PTB+ and Smooth PTB+ generally perform better than TB+, indicating the benefit of predictive methods and smoothing techniques in achieving faster convergence to the Nash equilibrium. The choice between quadratic averaging and last iterate methods depends on the game being considered.

This figure compares the performance of three different Blackwell approachability-based algorithms for solving extensive-form games. The algorithms are Treeplex Blackwell+ (TB+), Predictive Treeplex Blackwell+ (PTB+), and Smooth PTB+. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the duality gap, which measures how far the average strategies are from a Nash equilibrium. The figure shows that PTB+ and Smooth PTB+ generally outperform TB+, and that using the last iterate (rather than averaging over all iterates) can improve performance in some cases. The algorithms all use alternation in the self-play framework.

This figure compares the performance of three different algorithms: TB+, PTB+, and Smooth PTB+, all using quadratic averaging and the last iterate, and all using alternation. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the duality gap, a measure of how close the algorithms are to finding a Nash equilibrium. The graph shows how the duality gap decreases over iterations for each algorithm, allowing for a comparison of their convergence rates. The results indicate that PTB+ and Smooth PTB+ generally outperform TB+.

This figure compares the performance of three different algorithms (TB+, PTB+, and Smooth PTB+) in solving extensive-form games. Each algorithm uses a different approach to Blackwell approachability on treeplexes, and they differ in whether they are stepsize invariant and what convergence rate they achieve. The graph displays the duality gap (a measure of how far the algorithm is from reaching Nash Equilibrium) over the number of iterations. The results show that PTB+ and Smooth PTB+ perform similarly and generally outperform TB+.

This figure compares the performance of three different Blackwell approachability-based algorithms for solving extensive-form games: TB+, PTB+, and Smooth PTB+. Each algorithm uses a different approach to regret minimization and step size management. The plot shows how quickly the duality gap (a measure of how far from Nash equilibrium the algorithms are) decreases over time (iterations) for several benchmark games (Kuhn Poker, Leduc Poker, Liar’s Dice, Goofspiel, and Battleship). The results show the impact of different approaches on convergence speed and the importance of stepsize invariance in achieving good practical performance.

This figure compares the performance of three different algorithms: TB+, PTB+, and Smooth PTB+. Each algorithm is tested with quadratic averaging and the last iterate, and all use alternation. The plot shows the duality gap (a measure of how far from a Nash Equilibrium the algorithms are) versus the number of iterations for five different games. The goal is to show how the different algorithms perform in practice relative to their theoretical convergence rates and stepsize properties.

This figure compares the convergence performance of four different algorithms (PTB+, CFR+, PCFR+, and SC-POMD) for solving extensive-form games. The y-axis represents the duality gap, a measure of how far the algorithm’s current solution is from a Nash Equilibrium. The x-axis shows the number of iterations. Each line represents a different algorithm, with variations in averaging schemes (linear vs. quadratic) indicated. The figure illustrates the relative convergence speed of each algorithm across different game instances (Kuhn, Leduc, Liar’s Dice, Goofspiel, and Battleship).

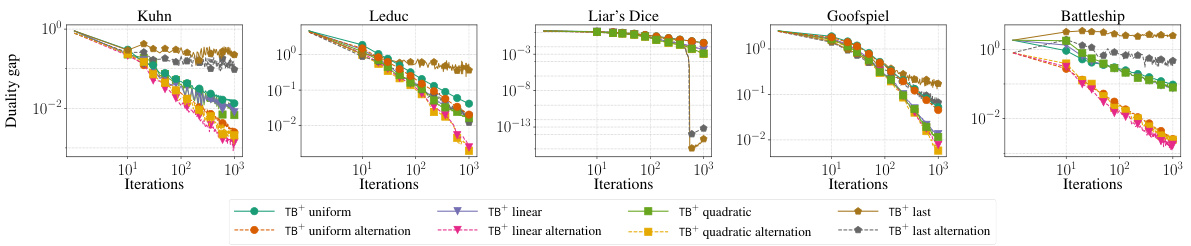

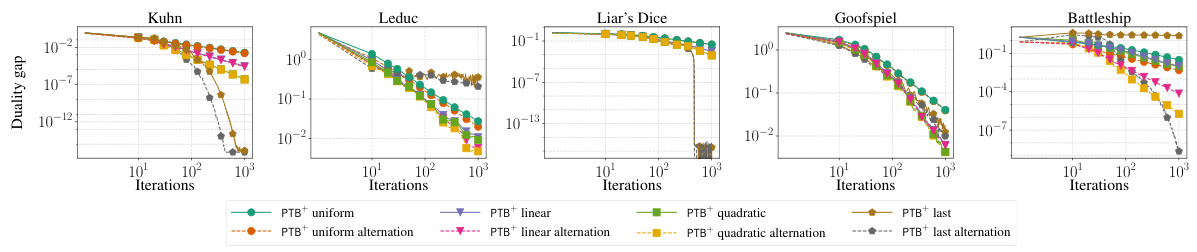

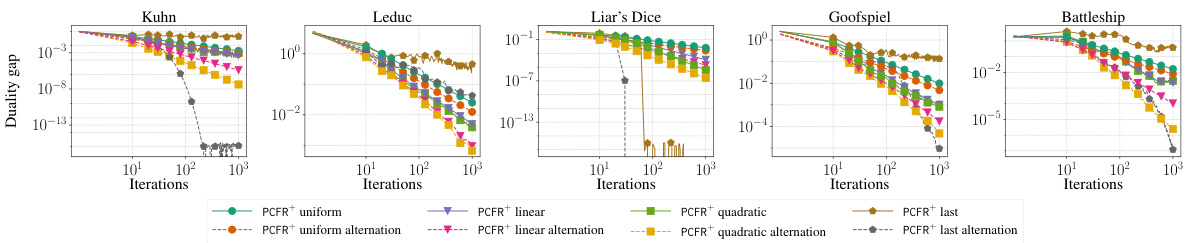

This figure compares the convergence of PCFR+ (Predictive Counterfactual Regret Minimization+) to Nash equilibrium in various games (Kuhn Poker, Leduc Poker, Liar’s Dice, Goofspiel, and Battleship). Different averaging schemes (uniform, linear, quadratic) and the last iterate are compared. Alternation, a technique to improve the convergence of the algorithm, is also examined both with and without its use. The y-axis shows the duality gap, a measure of how far from equilibrium the strategies are. The x-axis represents the number of iterations.

The figure shows the convergence to Nash Equilibrium for four different algorithms: PTB+, CFR+, PCFR+, and SC-POMD, across five different benchmark extensive-form games (EFGs). Each line represents a different algorithm, showing the duality gap over the number of iterations. The algorithms are compared using both alternation and quadratic averaging, except CFR+, which uses linear averaging. The graph helps illustrate the relative performance of different algorithms in solving EFGs.

More on tables

This table presents the convergence rate and stepsize invariance properties of several algorithms for solving two-player zero-sum extensive-form games (EFGs). The convergence rate indicates how quickly the algorithm approaches a Nash equilibrium (O(1/√T) or O(1/T)), while stepsize invariance refers to whether the algorithm’s performance is affected by the choice of stepsize parameters (infoset stepsize invariance or treeplex stepsize invariance).

The table presents the convergence rates and stepsize invariance properties of several algorithms for solving two-player zero-sum extensive-form games (EFGs). It compares algorithms based on counterfactual regret minimization (CFR), online mirror descent (OMD), and the newly proposed Blackwell approachability methods. Stepsize invariance is a key property highlighted in the paper, indicating whether algorithm performance depends on the choice of stepsize parameters.

This table summarizes the convergence rates and stepsize invariance properties of various algorithms for solving two-player zero-sum extensive-form games (EFGs). It compares the theoretical convergence rate (O(1/√T) or O(1/T)) with the type of stepsize invariance exhibited by each algorithm. Infoset stepsize invariance means the algorithm’s iterates are unaffected by the choice of different stepsizes at different infosets. Treeplex stepsize invariance means the iterates are unaffected by rescaling all stepsizes by a constant.

This table presents the convergence rates and stepsize invariance properties of various algorithms for solving two-player zero-sum extensive-form games (EFGs). The convergence rate indicates how quickly the algorithm approaches a Nash equilibrium, while stepsize invariance refers to whether the algorithm’s performance is affected by the specific values of stepsizes used. The table compares several algorithms, including CFR+, PCFR+, EGT, POMD, PTB+, Smooth PTB+, AdaGradTB+, and AdamTB+, highlighting their different convergence characteristics and stepsize properties.

This table presents the convergence rates and stepsize invariance properties of several algorithms for solving two-player zero-sum extensive-form games. It compares algorithms such as CFR+, PCFR+, EGT, POMD, and the novel algorithms introduced in the paper (PTB+, Smooth PTB+, AdaGradTB+, AdamTB+). Stepsize invariance refers to whether the algorithm’s iterates are unaffected by scaling the step size; infoset stepsize invariance is a stronger version specific to CFR+ family algorithms. The convergence rates indicate how quickly the algorithms approach a Nash Equilibrium (O(1/√T) or O(1/T)).

Full paper#