↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Proc. ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Imitation learning (IL) aims to train agents by mimicking expert behavior. Behavior cloning (BC), a simple offline IL method, suffers from a supposedly unfavorable quadratic dependence on the problem horizon (the length of the sequence of decisions). This has motivated the development of various online IL algorithms which require the ability to repeatedly query the expert for guidance and achieve better (linear) scaling with horizon. This paper revisits this apparent gap between online and offline IL.

The paper uses learning-theoretic analysis to show that the performance of offline BC, when using logarithmic loss, is often horizon-independent, even for deep neural networks as policy classes, when appropriate conditions on cumulative payoff range and supervised learning complexity are satisfied. It then shows that for deterministic, stationary policies, offline BC achieves linear dependence on horizon under certain conditions, contradicting previous findings. This challenges the prevalent notion that online methods are fundamentally better than offline ones. The paper also shows that even when dealing with stochastic policies, online methods do not always improve over offline ones.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in imitation learning. It challenges the prevailing assumptions about the superiority of online methods over offline methods by providing novel theoretical analysis and empirical validation. The findings open new avenues for improving offline algorithms and rethinking the design of online approaches, significantly advancing the field.

Visual Insights#

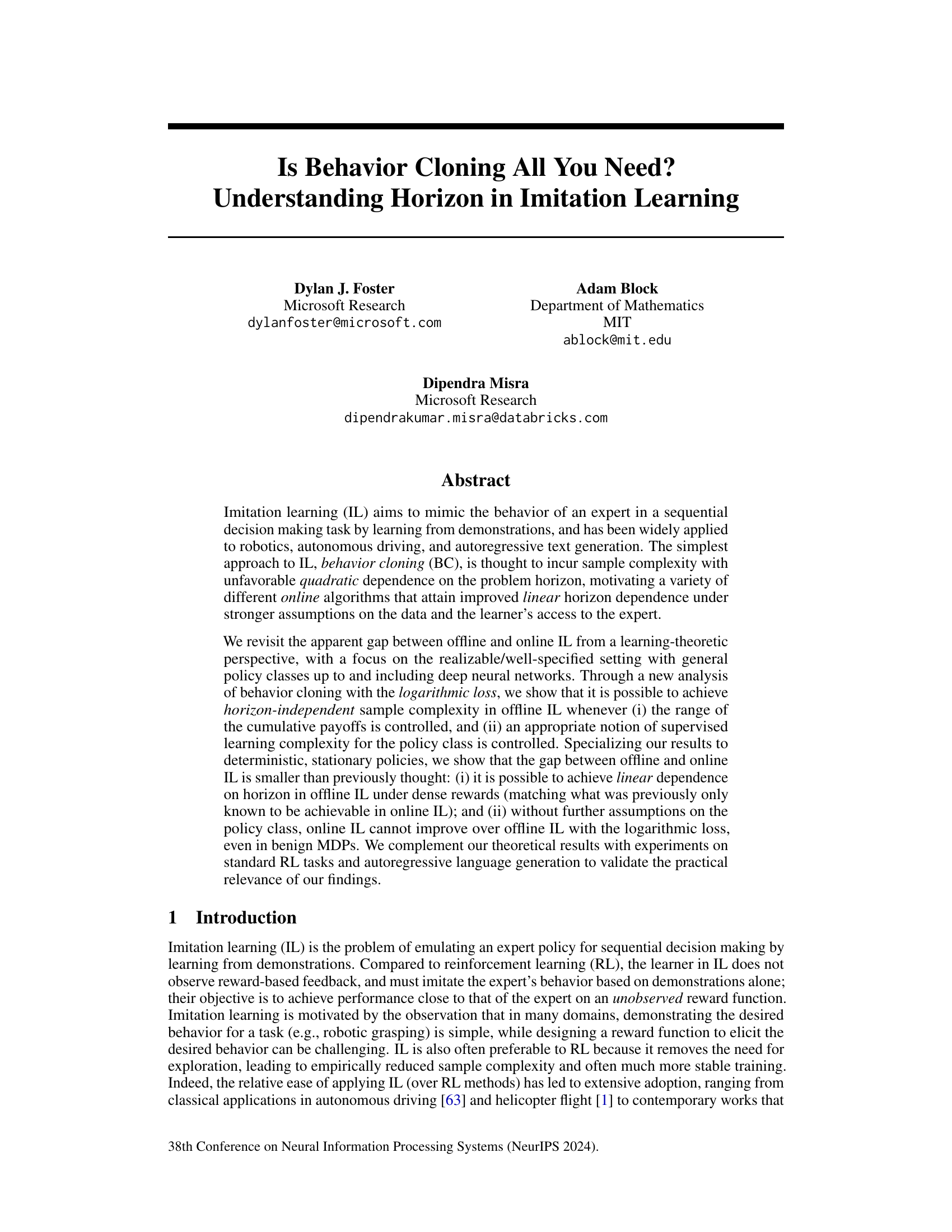

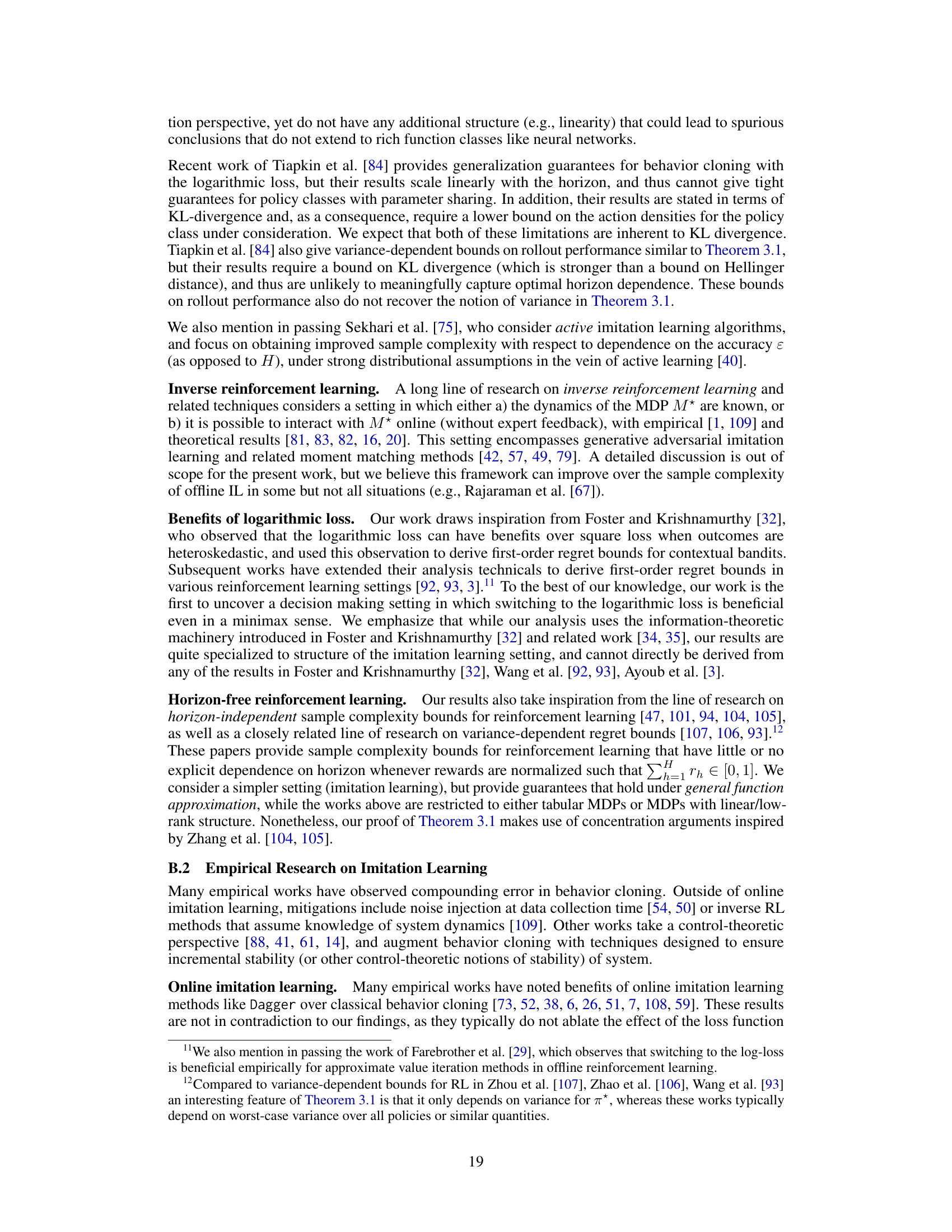

The figure shows the suboptimality (regret) of a policy learned using LogLossBC plotted against the number of expert trajectories for different horizons (H). Two environments are shown: MuJoCo (continuous control) and Atari (discrete control). The results indicate that the regret is largely independent of the horizon, supporting the paper’s theoretical findings.

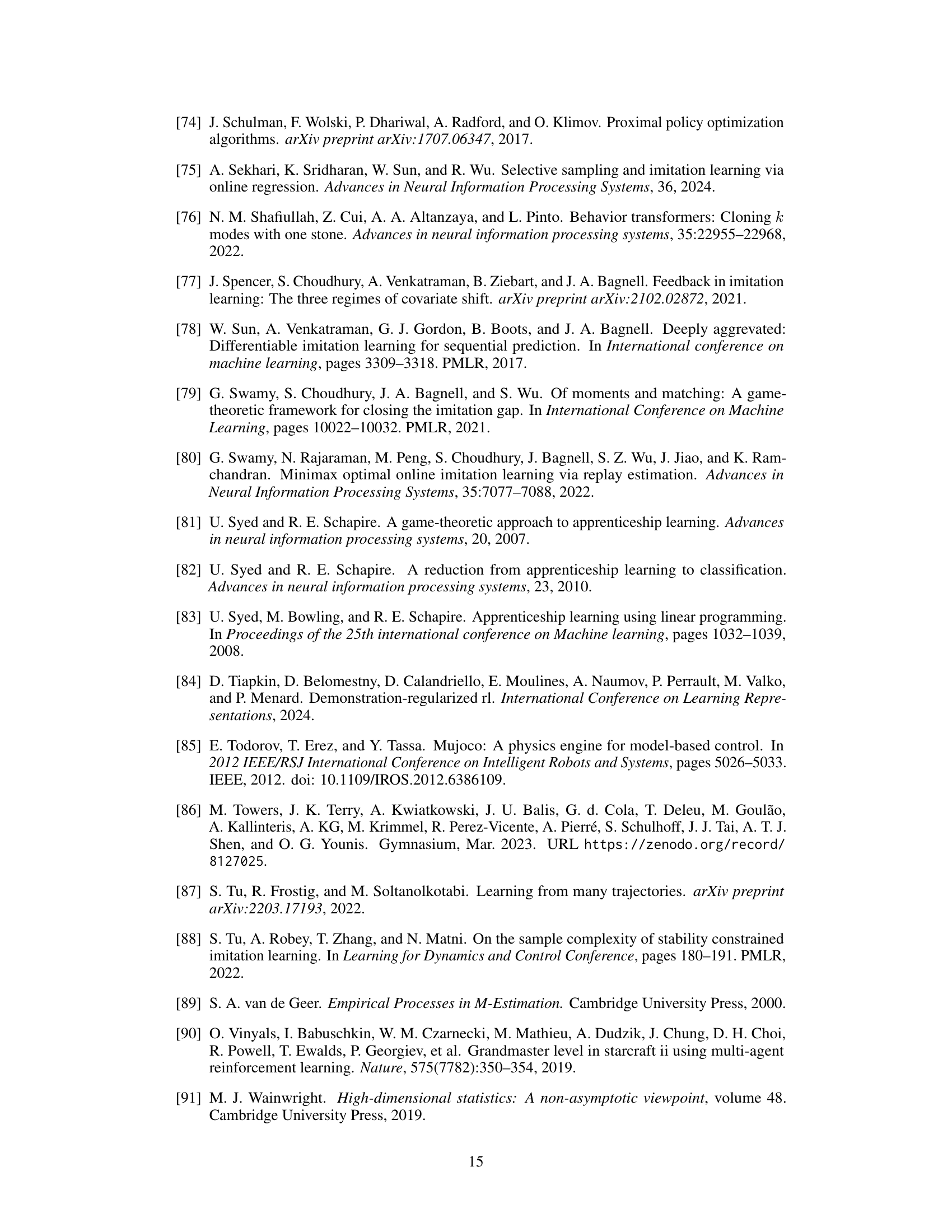

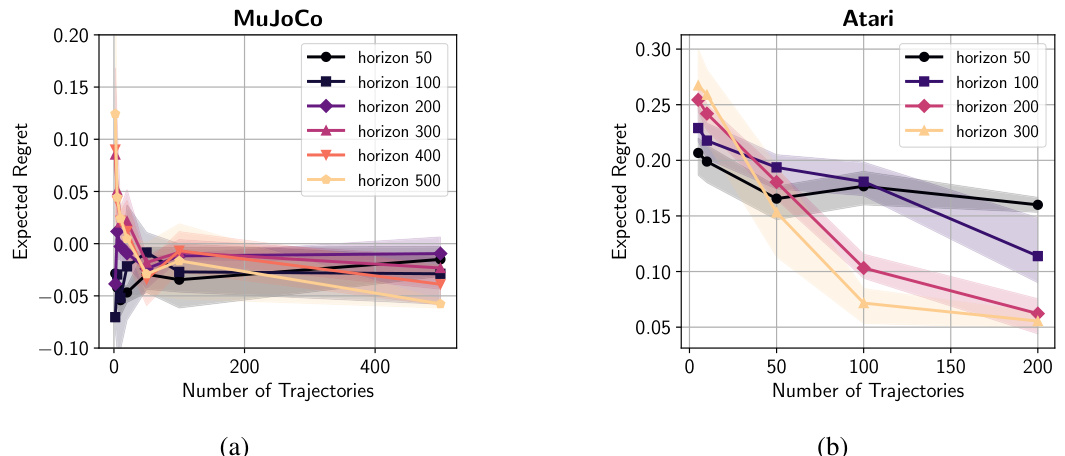

This table summarizes upper bounds on the regret of LogLossBC for deterministic expert policies, categorized by parameter sharing (yes/no) and reward density (sparse/dense). It highlights that under parameter sharing, the horizon dependence can be linear (dense rewards) or independent (sparse rewards). Without parameter sharing, quadratic dependence on the horizon is generally unavoidable, emphasizing the benefits of parameter sharing for efficient offline imitation learning.

In-depth insights#

Horizon’s Impact#

The research paper delves into the crucial role of ‘horizon’ in imitation learning, particularly its impact on sample complexity. A key finding is the surprising result that the dependence on horizon, often assumed to be quadratic, can be significantly mitigated or even eliminated under certain conditions. The authors demonstrate this by providing a novel analysis of behavior cloning, showing horizon-independent sample complexity can be achieved when rewards are properly normalized and the policy class complexity is controlled. This challenges the conventional wisdom, suggesting that the gap between offline and online imitation learning might be smaller than previously believed. The paper further investigates the impact of stochasticity on horizon dependence, finding that for stochastic policies, a quadratic dependence can still be necessary in certain scenarios; however, they also demonstrate that variance-dependent sample complexity can improve the dependence on horizon. The study highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of imitation learning algorithms, moving beyond simplistic assumptions about horizon’s impact and accounting for crucial factors like reward structure and policy class characteristics.

LogLossBC Analysis#

The analysis of LogLossBC (Log-loss Behavior Cloning) is a crucial part of the research paper, offering a fresh perspective on offline imitation learning. The core contribution is demonstrating that LogLossBC can achieve horizon-independent sample complexity under specific conditions. This challenges the conventional wisdom that offline IL suffers from a quadratic dependence on the horizon. The analysis reveals that horizon independence is attainable when the cumulative rewards are normalized and the supervised learning complexity of the policy class is controlled. This implies that for deterministic and stationary policies, linear horizon dependence is achievable in offline imitation learning, a result previously thought to only be possible in online settings. However, the analysis also reveals that without additional assumptions on policy class structure, online imitation learning, even with the benefit of recoverability, cannot improve upon offline LogLossBC in the realizable setting. This finding is significant as it shows that the apparent gap between offline and online imitation learning methods, in terms of horizon dependence, may be less substantial than previously understood. The tight sample complexity bounds for both deterministic and stochastic policies provided further clarify the impact of horizon on imitation learning, underscoring the importance of LogLossBC in achieving horizon independence under specific conditions.

Offline vs. Online IL#

The core of the paper revolves around contrasting offline and online imitation learning (IL). Offline IL uses a fixed dataset of expert demonstrations, making it readily applicable but susceptible to distribution shifts, potentially leading to suboptimal performance. Online IL, conversely, allows the learner to interactively query the expert during training, mitigating distribution shift issues. The authors challenge the established view that online IL is inherently superior. Their analysis centers on the role of the problem’s horizon (length of the sequential decision-making task). Surprisingly, they demonstrate that offline IL using behavior cloning with the logarithmic loss can achieve horizon-independent sample complexity under certain conditions (controlled cumulative rewards and supervised learning complexity), significantly improving upon prior results. For deterministic policies, this means offline IL can match the linear horizon dependence previously thought achievable only with online methods. However, online IL doesn’t universally outperform offline IL. The study reveals that without additional assumptions on the policy class, online IL offers no advantage over offline IL, even in favorable scenarios. This underscores that the choice between offline and online IL should be guided by factors beyond simply the horizon, emphasizing the practical relevance of offline algorithms.

Stochastic Policies#

The section on “Stochastic Policies” likely delves into the complexities of imitation learning when the expert’s behavior is not deterministic but rather probabilistic. This introduces significant challenges because the learner must now model not only what actions the expert takes but also the probability distribution over those actions. The analysis would likely explore how the uncertainty inherent in stochastic policies impacts sample complexity, potentially showing a tradeoff between the accuracy of the imitation and the amount of data needed. The authors probably investigate the effects of this uncertainty on error amplification, demonstrating that stochastic policies can significantly exacerbate the problem of distribution shift encountered in offline imitation learning. This section most likely presents new theoretical results, possibly including variance-dependent bounds, that characterize the optimal sample complexity for imitation learning under stochastic expert policies. The findings would likely emphasize the challenges of offline learning in this setting and discuss whether or not online methods, such as DAgger, offer a significant advantage in terms of sample efficiency. Finally, the authors might compare and contrast the results obtained for stochastic policies with those for deterministic policies, highlighting the key differences in performance and sample complexity.

Future Directions#

The “Future Directions” section of this research paper would ideally delve into several key areas. First, it should address the limitations of the current LogLossBC algorithm and suggest potential improvements. This might include exploring different loss functions or incorporating techniques to mitigate error amplification and distribution shifts. Secondly, the authors could discuss extending their theoretical framework to more complex scenarios. This could involve relaxing assumptions about the policy class or the environment, such as investigating misspecified settings or handling non-stationary policies. Third, future work might focus on integrating their insights with other imitation learning approaches. This could involve incorporating ideas from inverse reinforcement learning, or combining offline and online learning methods to achieve both sample efficiency and stability. Finally, the paper could explore the practical implications of their findings by suggesting applications in real-world problems, such as robotics, autonomous driving or natural language processing. Specifically, exploring the potential impact of the horizon-independent sample complexity results on scaling these approaches to more complex tasks would be valuable.

More visual insights#

More on figures

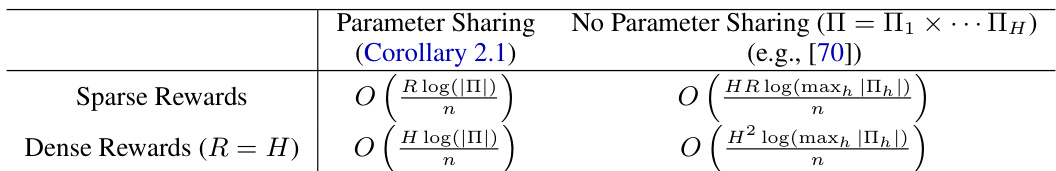

This figure shows the dependence of expected regret on the horizon for different number of trajectories in two environments: MuJoCo Walker2d-v4 and Atari BeamRiderNoFrameskip-v4. The results indicate that increasing the horizon does not significantly affect the regret, which supports the theoretical findings of the paper.

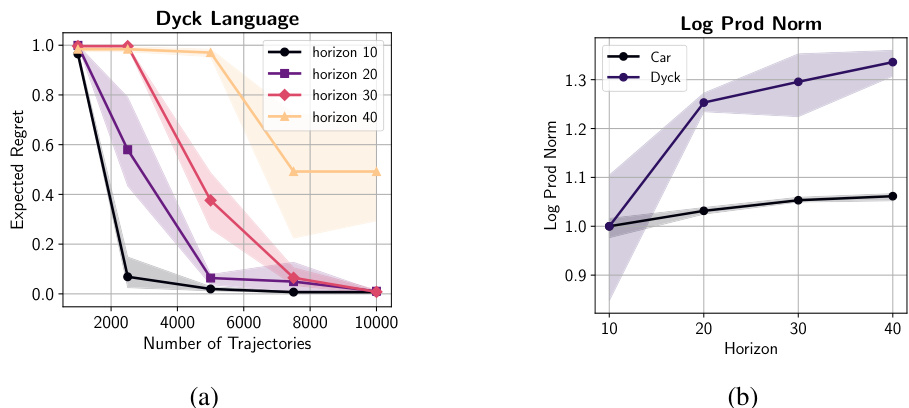

This figure shows the relationship between the number of expert trajectories, expected regret, and model complexity for the Dyck language generation task. The left panel (a) displays how expected regret increases with horizon length (H) for different numbers of expert trajectories. The right panel (b) illustrates the growth in model complexity (measured by log product norm) as the horizon increases for Dyck and Car environments. The results suggest that increasing model complexity with increasing H contributes to higher regret in Dyck, while the Car environment exhibits much less sensitivity to horizon.

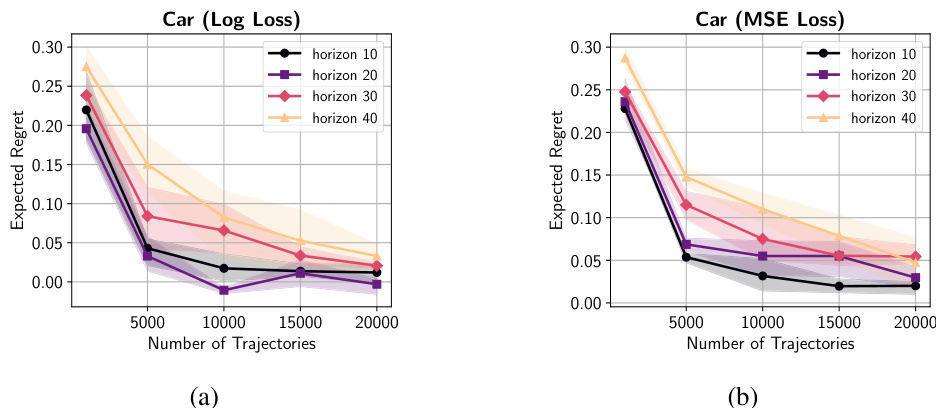

This figure shows the relationship between expected regret and the number of expert trajectories in the Car environment for both log-loss and mean-squared loss functions. The results are presented for various horizon values (H). The key observation is that while regret decreases with increasing numbers of trajectories (as expected), a slight increase in regret is observed with increasing horizon values. This suggests a mild dependence of regret on the horizon.

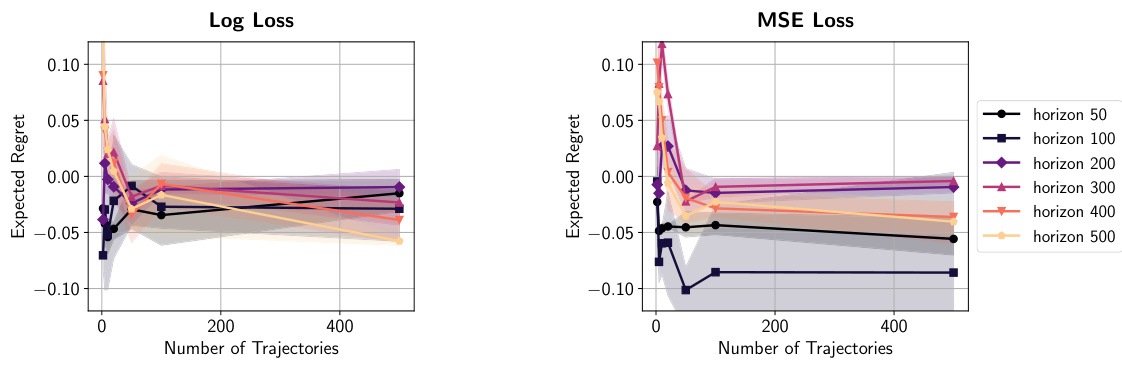

This figure displays the relationship between the expected regret and the horizon (H) for different numbers of trajectories (n) using two different environments: MuJoCo Walker2d (continuous control) and Atari BeamRider (discrete control). For both, the regret does not increase significantly with the horizon. The results support the paper’s theoretical findings that show the sample complexity for log-loss behavior cloning is horizon-independent.

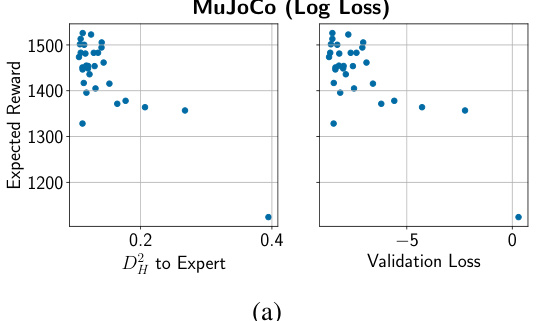

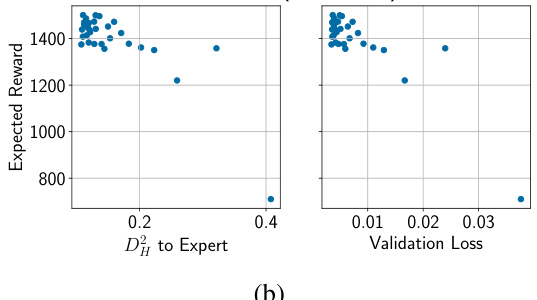

This figure shows the relationship between the Hellinger distance to the expert policy, the validation loss, and the expected reward of the learned policy for two different loss functions: LogLossBC and MSE Loss. It demonstrates that Hellinger distance serves as a better proxy for rollout performance compared to validation loss, especially when using LogLossBC.

The figure shows the suboptimality (regret) of a policy learned using log-loss behavior cloning as a function of the number of expert trajectories and the horizon (H). Two plots are shown: one for a continuous control environment (MuJoCo Walker2d-v4) and another for a discrete control environment (Atari BeamRiderNoFrameskip-v4). The key finding is that the regret is largely independent of the horizon, which supports the paper’s theoretical claims.

Full paper#